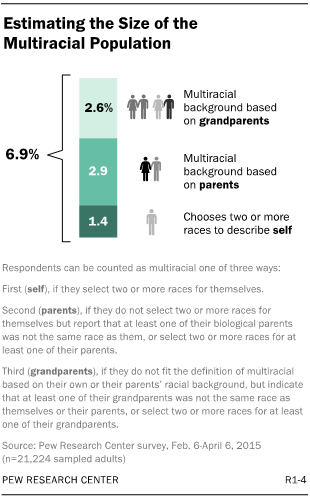

Today, Pew Research Center released its first report on American multiracial adults, a group that comprises an estimated 6.9% of the adult population, or nearly 17 million adults. The report looks at who they are demographically, their attitudes and experiences, and the spectrum of their racial identity.

Overall, America’s multiracial population is growing three times as fast as the population as a whole, and it is poised to triple by the middle of this century, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Yet just shy of 50 years ago, interracial marriage was illegal in more than a dozen Southern states. And it was not until 2000 that the Census Bureau began allowing people the option of selecting more than one race for themselves.

We asked researcher Rich Morin, one of the authors of the report, about Pew Research’s interest in studying this group, what researchers learned and how they conducted the study.

First, why the interest in studying multiracial Americans?

We were drawn to this topic because it’s timely, it’s important and it’s absolutely fascinating. We also learned soon after we started that it’s very, very difficult. First of all, just defining who is multiracial was a big task.

As researchers specializing in social trends, the topic had immediate appeal and it’s also a natural extension of our other work on race and ethnicity. The multiracial population is growing at a remarkable pace; even the projected growth rate you cite may be too conservative. Yet we discovered while doing preliminary research for this study that there are no major nationally representative surveys of multiracial Americans. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first one that has ever been done.

Part of the reason behind the absence of data on this group is the size of the multiracial population – it’s still relatively small. As you note, we estimate that only about 6.9% of the adult population has a mixed-race background. And by the Census Bureau’s definition the share is just 2.1%. That means even large, nationally representative surveys typically include too few mixed-race adults to analyze, much less contain sufficiently sized samples of individual multiracial groups such as white and black or white and Asian biracial adults.

The study of the multiracial population also offers a unique window into race relations in the United States: where they have been, where they are now and where they may be heading. Sensitive issues such as the black-white racial divide take on a new perspective when viewed through a multiracial lens. For example, about three-in-ten white and black biracial adults (31%) say their racial background is “essential” to their sense of personal identity, compared with 55% of single-race blacks but only 20% of single-race whites.

The first challenge in doing a study like this is to figure out how you count multiracial Americans. You could have just gone with asking people if they identify as multiracial or more than one race. Or you could have used the census question. But you did neither one. Explain what you decided to do and why.

Determining who is multiracial was not only the first challenge we faced; it was also the biggest. We began by collecting as many ways to measure racial background as we could find. Then we tested five different promising approaches before deciding how we would do it in our survey.

At each step along the way, we learned something important. We’ll prepare a report for later release that will summarize each one of our tests and what we learned, so I will briefly describe only two here.

As it happens, we tested both approaches you mention in your question using the Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel, a nationally representative sample of adults 18 and older. In one test we simply asked adults whether they considered themselves to be mixed race. About 12% of them said they were. The problem is, our tests, as well as data from other studies that have used this approach, revealed that a significant share of the public confuse race and ethnicity. When those who consider themselves to be multiracial are asked to identify their racial background, many responded that they were two or more ethnic groups such as “Irish and Italian.” Clearly this question would lead to an overestimate of the mixed-race population by including people with multiethnic but not multiracial backgrounds.

We also tested a version of the race question that was used by the U.S. Census Bureau in an experiment it conducted in 2010. Among other things, this question allowed people to select more than one race or origin and also included “Hispanic” as one of the choice options instead of asking a separate question to capture Hispanic origin. We tested this question and a follow-up question that asked respondents if either parent was a different race or origin than they were. We found that many people who only chose a single race for themselves reported that they had parents of a different racial background. In fact, the percentage of multiracial adults more than doubled when the backgrounds of parents was considered.

This was a “Eureka!” moment for us – we realized that by just asking people their race, even if we allowed them to choose more than one, we might be missing something. This finding was confirmed in our final survey. About three-quarters of all adults with a mixed racial background listed only a single race for themselves – much like President Obama, whose father is black and mother is white, who listed his race only as black when he filled out his 2010 census form.

We decided to cast a wide net in measuring the multiracial population. We first asked people to report their race using a question closely modeled after the 2010 census experimental question we had asked previously. But we then also asked them the racial backgrounds of their biological mother and father and also their grandparents using a question in a similar format. Together, these questions became the basis for our estimate of the multiracial population. (For the exact questions we used to measure racial background, see our methodology appendix.)

This new approach gave us tremendous flexibility. Not only did we find out how people report race, we could see how many Americans marked only one race for themselves but had a mixed-race background when their parents’ or grandparents’ racial makeup was considered. We also could see in which generation a different race or races appeared in the family tree, and how multiracial identity persists or fades over the generations.

Your study found that a majority – 61% – of Americans with a multiracial background did not identify as “multiracial or mixed race.” That’s a pretty big number. Does that negate your findings or estimate of this group?

No, just the opposite. The number you cite is one of the singular findings of this study and is critical to understanding the multiracial experience. We call it the “multiracial identity gap.”

We had discovered in some of our early survey tests that most mixed-race adults did not consider themselves to be multiracial. We wanted to understand this response, so in the final survey we asked this group why they did not consider themselves to be multiracial.

About half – 47% – say it was because they were raised as one race, and an equal share report they look like one race. About four-in-ten say they identify closely with one of their races and about a third say they never knew their family member who was a different race. (Respondents could select more than one reason.)

What this told us in a powerful way is that being multiracial is not just the sum of races in an individual’s family tree. It’s as much an attitude as it is a biological certainty – a combination of nature and nurture.

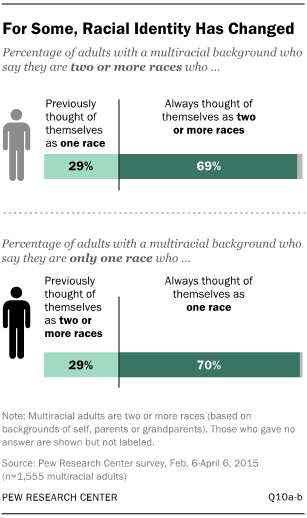

Another finding drove home the fluid nature of racial identity. About three-in-ten mixed-race adults in the survey say they have changed the way they viewed their racial background over the course of their lives. Some 29% say they once thought of themselves as only one race but now consider themselves more than one race, and an equal share say that they moved in the opposite direction.

The largest multiracial groups are those who are either American Indian and white or American Indian and black. Yet majorities in both of these groups do not consider themselves “multiracial.” What do you think accounts for that?

On a number of key questions, our survey finds that mixed-race adults with a Native American background have only faint connections to their American Indian ancestor or ancestors. (For more on racial identity among American Indians, see this separate analysis.)

For example, among white and American Indian biracial adults, only 22% say they have “a lot” in common with American Indians, while 61% say they have a lot in common with whites. Similarly, black and American Indian biracial adults are far more likely to say they have a lot in common with blacks than with American Indians (61% vs. 13%). And only small shares of multiracial adults with Native American backgrounds say they have close ties to the American Indian side of their family.

So, who are multiracial Americans? What, if anything, do they have in common?

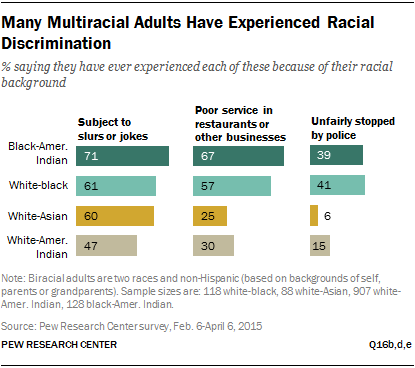

Some attitudes are commonly shared across the major multiracial groups. Fully six-in-ten multiracial Americans, including large shares across each of the major multiracial groups, say they are proud of their mixed racial background, and about the same percentage say their background has left them more open to different cultures. And most multiracial Americans, like other minorities, have experienced some form of racial discrimination ranging from racial slurs to physical threats.

But one of the more important findings of this study is that multiracial Americans are not a single, easily characterized group, but an aggregation of many people with different racial combinations. Each group comprised of a shared racial background, such as white and black or white and Asian, is distinctive from the others in terms of their attitudes and life experiences. Overall, we found the differences among the groups to be more interesting and significant than what these groups had in common.

For example, our survey found that white and black biracial Americans have strong social and family ties with blacks, and they are much more likely to say they have a lot in common with blacks than with whites. Among white and Asian biracial adults, it was nearly the opposite: They are more likely to say they have a lot in common with whites than Asians.

And what about Hispanics? Are they counted as multiracial, for example, if someone says they are Hispanic and white or Hispanic and black? What about people of Middle Eastern or North African descent? Are they included as multiracial?

We followed the Census Bureau’s lead on this and did not count individuals as multiracial unless they marked two of the five census races (white, black, Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander). The Census Bureau considers having a Hispanic background to be an individual’s ethnicity or origin and not a race. And they consider people with a Middle Eastern background as “white” (one’s specific Middle Eastern background can be indicated in the ancestry question). So someone who is one of the five census races and indicates a Hispanic origin or Middle Eastern ancestry is considered single race to census takers.

That said, some Americans with a Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) background have pressed to include a separate ethnic category for the MENA region, similar to Hispanic origin. Some Hispanics also believe that Hispanic should be considered as a racial group. There also are long-standing questions about why the Asian racial category includes people from India, Pakistan and other Southwest Asian backgrounds along with Chinese, Japanese and other East Asian groups.

You experimented with a question in the survey that asked Hispanics if they considered being Hispanic to be a part of their racial background. Why did you do this and what did you find?

Census has found that many Latinos do not choose one of the standard racial classifications offered. Instead, more than any other group, Latinos say their race is “some other race,” mostly writing in responses such as “Mexican,” “Hispanic” or “Latin American.” In 2010, more than a third – 37% – of all Hispanics answered the race question this way.

These findings prompted us to wonder if Hispanics consider their Hispanic background to be part of their racial background, their ethnic background or both. So we posed that question to our survey respondents who marked “Hispanic” as one of their races or origins.

Our experiment found that 11% of adults who self-identify as Hispanic say that their Hispanic background is part of their racial background, 19% consider it part of their ethnic background and 56% consider it part of both their racial and ethnic backgrounds. Taken together, two-thirds (67%) of Hispanic adults describe their Hispanic background as a part of their racial background.

When you add in the share of Latinos who give one census race and also consider their Hispanic background to be their race or both their race and ethnicity, the estimate of the multiracial population in the U.S. increases from 6.9% to 8.9%.

What can be gleaned from the multiracial population as a demographic group, and how could you see this translating into politics or issues about race?

We explore the politics of the multiracial population in some depth in our report. Overall, multiracial Americans tend to resemble the country as a whole. A modest majority (57%) supports or leans toward the Democratic Party, while 37% identify with or lean to the Republicans. The figures for the country as a whole aren’t much different: About half (53%) favor the Democrats, while 41% line up with the GOP. So these findings suggest little difference in terms of politics between multiracial Americans and the rest of the country.

But, as we saw elsewhere, such summary numbers tell only part of the story, and often the least interesting part. Our survey found real differences in the politics and ideology of the major multiracial groups. And what was particularly striking to us was how the politics of the different multiracial groups tended to mirror the politics of the minority race in an individual’s background.

Multiracial Americans with an African-American background strongly favor the Democratic Party, similar to the party preferences of single-race blacks. For example, about nine-in-ten biracial black and American Indian adults (89%) identify or lean toward the Democratic Party – and so do 92% of all single-race blacks. The politics of black and American Indian and white, black and American Indian Americans demonstrate a similar pattern. (We had too few single-race American Indians to analyze.)

White and Asian biracial adults also tend to line up with the Democratic Party (60% vs. 38% for the Republicans), and so do single-race Asians (68% vs. 26%).

Biracial white and American Indians resemble single-race whites in their party identification. This is the only major mixed-race group where Republicans hold the edge, 53% to 42%. We didn’t have enough single-race American Indians in our sample to measure their party ID.