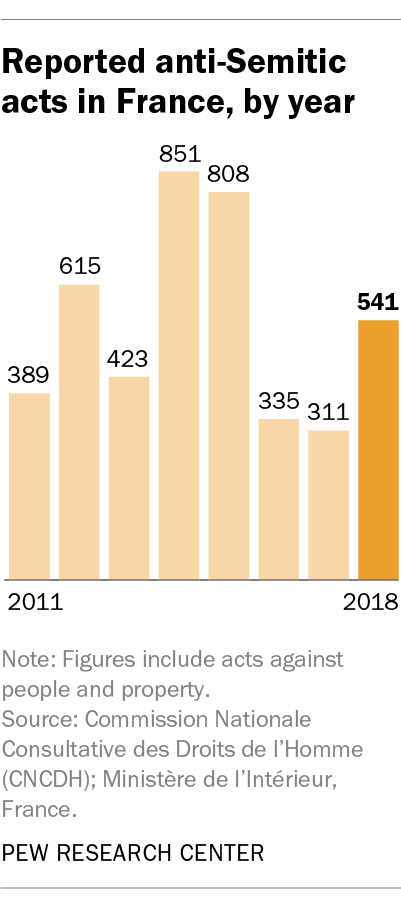

In France, home to Europe’s largest Jewish population, reports of anti-Semitic incidents rose dramatically in 2018. There were 541 cases reported last year – not as high as in some previous years, but a 74% increase from 2017, according to the country’s Ministère de l’Intérieur. And already in 2019, there have been several new high-profile anti-Semitic incidents, including swastikas being spray-painted on graves in a Jewish cemetery.

Prominent though these incidents may be, they run counter to public opinion in France. A 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that a majority of French adults reject negative Jewish stereotypes and express an accepting attitude toward Jews.

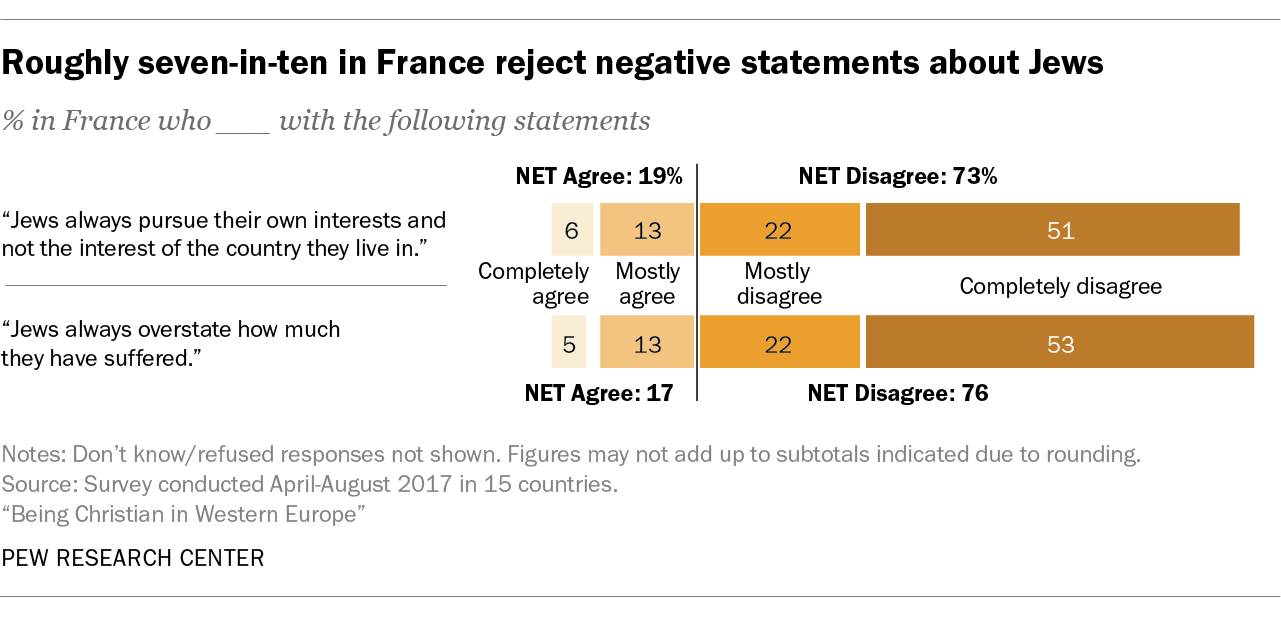

In the survey, conducted in France and 14 other Western European countries, the Center asked whether people agreed or disagreed with two strongly worded negative statements: “Jews always pursue their own interests and not the interest of the country they live in,” and “Jews always overstate how much they have suffered.” Roughly seven-in-ten or more French respondents either completely or mostly disagreed with these statements, while about one-in-five completely or mostly agreed with them.

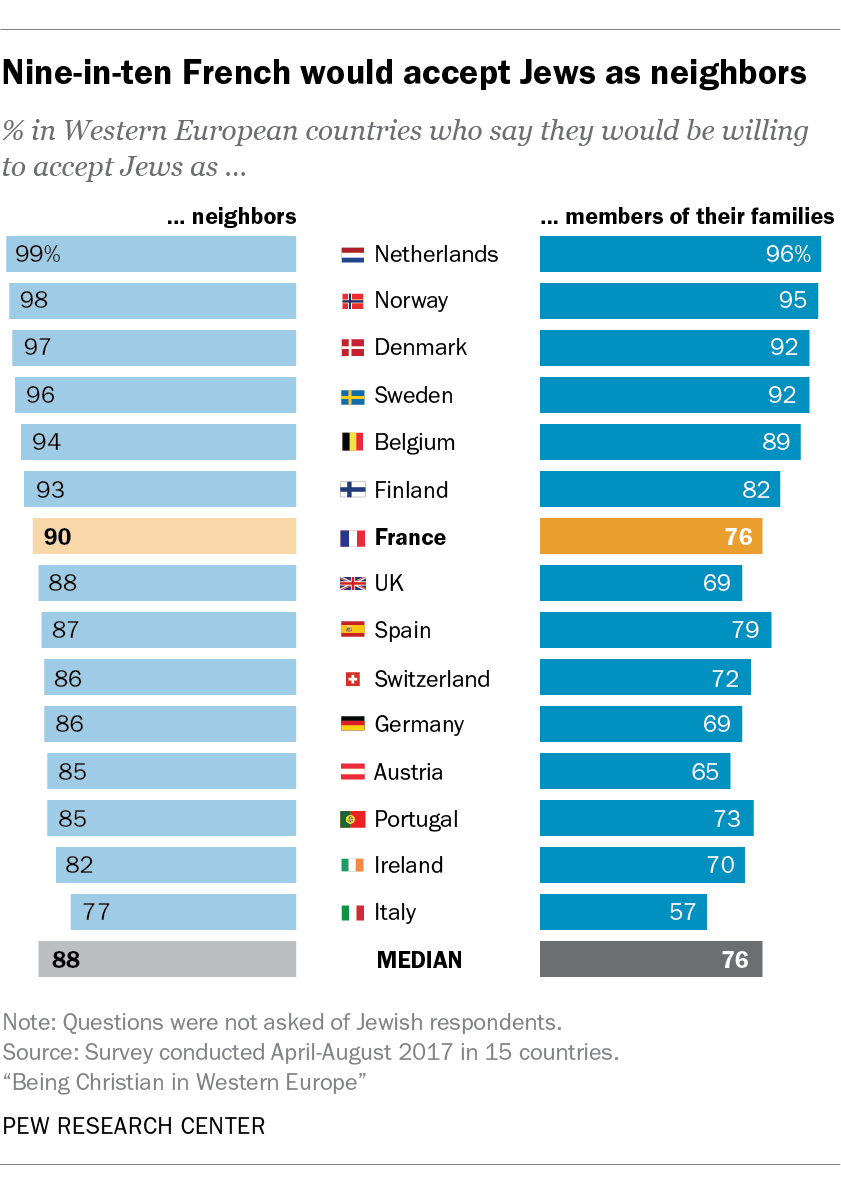

To gauge the extent of anti-Jewish sentiment in another way, the survey also asked Western European adults if they would be willing to accept Jews as neighbors or members of their family. Nine-in-ten French adults said they would be willing to accept Jews as neighbors, while roughly three-quarters (76%) said they would accept Jews as members of their family. These figures are at or near the median for the 15 countries where both questions were asked. (In Germany and the United Kingdom, where reported anti-Semitic incidents rose nearly 10% and 16% last year, respectively, the shares of adults saying they would accept Jews as neighbors and relatives were somewhat similar to those in France.)

On balance, French adults who identify as Christian are slightly more likely than people who identify as religiously unaffiliated (that is, atheist, agnostic or having no particular religion) to agree with anti-Jewish stereotypes, and they are slightly less likely to say they would accept Jews as relatives and neighbors. For example, 88% of Christians in France say they would accept Jews as neighbors, while 94% of the religiously unaffiliated in France say this. Respondents identifying with right-wing political ideology are considerably more likely to agree with the negative statements about Jews. The survey did not reach enough Muslims – who constitute France’s third-largest religious group, after Christians and the religiously unaffiliated – to allow for a nationally representative sample of their views.

It may seem counterintuitive that survey results would show widespread French acceptance of Jews less than a year before anti-Semitic incidents would rise. But general population survey data and statistics concerning anti-Semitic acts measure two different things. The former reflect a snapshot at a specific time of the attitudes of a nationally representative sample of adults, while the latter record reported events over time.

The number of Jews in France – as well as in the rest of Europe – has been declining since World War II. Some of this decline is due to emigration: In some recent years, France has been the largest origin country for immigrants to Israel – with 7,238 French emigrating there in 2014 and 7,328 doing so in 2015, according to the Jewish Agency for Israel. While estimates of France’s Jewish population vary, the number of Jews is France is believed to be as high as 500,000, or a little less than 1% of the country’s overall population.

The low share of Jews in France may help explain their relatively low profile across the country. A little over half of French adults (55%) say they know someone who is Jewish – lower than the 81% of French respondents who say they know an atheist and the 79% who say they know a Muslim. And just 33% of French respondents say they know “a great deal” or “some” about the Jewish religion, lower than the 42% who say they know “a great deal” or “some” about Islam and the 77% who say that about Christianity.

Knowing someone Jewish or knowing “a great deal” or “some” about Judaism are associated with somewhat higher levels of willingness to accept Jews as relatives, according to the Center’s survey. For example, 83% of French adults who say they know someone Jewish also say they would accept Jews as members of their family, while 67% of French adults who do not know anyone Jewish say this.