Measuring the identity of Taiwanese Americans, and Asian origin groups in the United States more generally, is a challenging endeavor, whether in survey research or when trying to generate estimates of population size, such as the Taiwanese American population through Census Bureau data. Pew Research Center generally tends to rely on self-identification when it comes to measuring identity, and in this section, we will explain how this applies to our survey’s Taiwanese sample.

In this report, we classify the Taiwanese sample – as well as the samples of other Asian origin groups – based on survey participants’ responses to a question about their ethnic identity. Ultimately, origin groups were categorized based on the answers of those who self-identified with one single Asian origin only. But a respondent’s identity can also be expressed through multiple, overlapping markers, such as birthplace, ancestry, or cultural and linguistic roots. To capture this complexity, the Center’s 2022-2023 survey of Asian American adults included a series of questions that probe these different markers.

To holistically grasp how a respondent self-identifies, the survey specifically inquired about their race and ethnicity, spoken and written language fluency, birthplace, as well as the birthplace of both parents. Many of these identity markers relate to overlapping concepts that rarely have clear definitions:

- Race is a concept that groups individuals together based on shared physical characteristics. The understanding of race in the United States may differ from how race is conceptualized in various countries across Asia. Through the U.S. lens, all Asian origin groups indiscriminately belong under the “Asian” race banner.

- Ethnicity is a concept that relates to a broader cultural identity that is shared by a group of people. People from multiple countries or nations, who may identify in disparate ways, can share one ethnicity.

- Nationality is a concept that relates to an individual’s ties to a particular country or nation. Nationality is often – but not always – associated with where one was born or holds citizenship.

- Ancestry is a concept that relates to an individuals’ familial ties to a particular country, nation, region or place. Ancestry is often associated with a particular place that someone can trace their cultural heritage or roots to, including the backgrounds of their parents or older generations.

All these concepts, and more, can shape how one sees their own identity. In the case of Taiwanese Americans, for instance, those who said they were born in Taiwan may imply that they are Taiwanese by nationality. Meanwhile, those who reported that only their parents were born in Taiwan might indicate that they possess Taiwanese ancestry. Additionally, people who have Taiwanese nationality or ancestry may or may not identify as Taiwanese themselves. These measures in particular point to the larger concept of a Taiwanese diaspora, or a population that lives outside of the place where they or their ancestors originated. In the Chinese language, the terms huá qiáo (华侨) and huá rén

(华人) refer to those of Chinese descent who currently reside outside their country of origin. A person of Taiwanese descent (tái wān rén, or 台湾人) may or may not identify with these Chinese diasporic concepts.

How we classify and report Asian origin groups

In our 2022-23 survey of Asian Americans, we primarily relied on one question to classify respondents into specific Asian origin groups. We asked how respondents identified ethnically by asking them to select specific Asian origin groups that they self-identify with. This particular question is key to determining how respondents personally differentiate between their Chinese and Taiwanese identities.

ASIANID_MOD. Do you consider yourself to be any of the following?

(Check all that apply.)

1. Chinese

2. Filipino

3. Indian

4. Korean

5. Vietnamese

6. Some other ethnicity (Please specify) ________

As respondents were permitted to choose more than one ethnicity, they can be categorized into any Asian group alone or in combination. For example, a person may identify as Vietnamese alone, while another may say that they are Chinese, Filipino and Japanese in combination. If someone identifies as Taiwanese, or other Asian origin groups that are not explicitly listed, they must enter that response under the “Some other ethnicity” box. This process is similar to how the U.S. Census Bureau has asked about Asian identity in their recent questionnaire.

When discussing Asian origin groups in this report, as well as in previous reports, we strictly relied only on the respondent’s self-identified ethnicity – their answer to the ASIANID_MOD question – and not on the more expansive markers of identity, which took into account broader identity markers such as birthplace and ancestry that were asked in the survey questionnaire.15

However, there are some challenges and limitations to this approach. First, when deciding how to define specific Asian origin groups for analysis, we only considered those who identified with one Asian origin group alone. We did this to ensure that there is no overlap between categories, allowing us to directly compare public attitudes between distinct, mutually exclusive origin groups.

Second, this understanding of Asian “origin groups” does not have a clear definition and is ultimately based on how respondents choose to self-identify. Even though ASIANID_MOD inquired about ethnic identity, respondents may have provided answers that actually speak more to their nationality, ancestry or other factors.

What may have driven some participants to respond with their nationality or ancestry instead of with their ethnicity? In some countries, ethnicity, nationality and ancestry are largely overlapping concepts; but in others, the relationship between these concepts is more complicated. This is particularly apparent in the case of the Taiwanese sample, where classifying respondents strictly by a shared Chinese ethnicity may obscure disparate identities for people who more strongly identify with Taiwanese nationality or ancestry. Past Pew Research Center analyses have found that among those who live in Taiwan, many do not consider themselves Chinese.

How does this apply to the Taiwanese sample in the 2022-23 Asian American survey?

In this report, we classify the Taiwanese sample the same way we classified all other Asian origin groups: by relying solely on responses to the ASIANID_MOD question. This means that we classify a respondent as Taiwanese American only if they explicitly self-identify as Taiwanese alone.

By contrast, a broader definition of the Taiwanese American sample in the survey would consider respondents who say that they are Taiwanese in addition to some other Asian origin group (primarily Chinese), as well as those who did not self-identify as Taiwanese, but were born in Taiwan or reported having at least one parent who was born in Taiwan.

Given the potential differing interpretations of the Taiwanese identity being either a nationality, ancestry or both, in this section, we examine how our reporting of the Taiwanese sample estimate and its resulting attitudes would differ if we were to use different, more expansive definitions of identity.

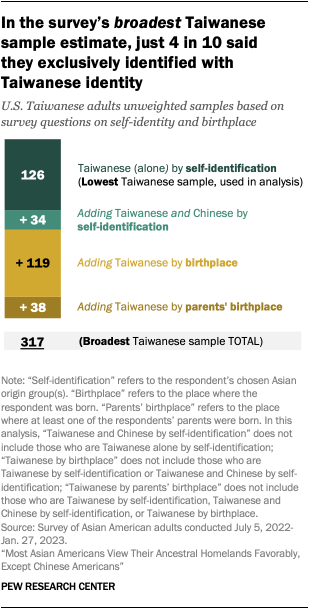

In the 2022-23 survey of Asian Americans, we conducted 126 interviews with respondents who self-identified as Taiwanese alone, which accounts for 40% of the respondents in the broadest Taiwanese sample. An additional 34 respondents self-identified as both Taiwanese and Chinese, or an additional 11% of the total estimate. Finally, 157 respondents did not self-identify as Taiwanese but have some connection to Taiwan because either they or at least one of their parents was born there. This last subgroup accounted for 50% of the most expansive definition of our Taiwanese sample, and all respondents self-identified as being of Chinese origin instead. All factors considered, we conducted a total of 317 interviews with respondents who have at least some Taiwanese background.

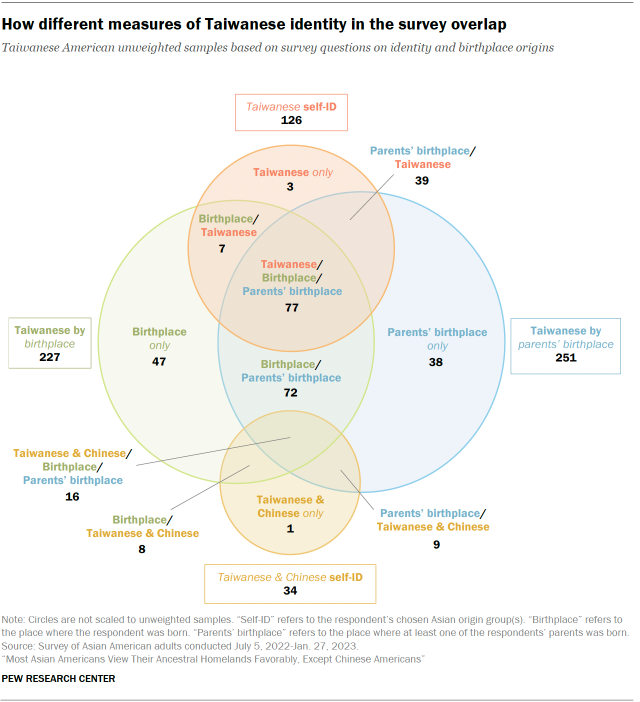

Significant overlap exists among these distinct measures of the Taiwanese identity, however. For example, among the 126 respondents who self-identified as being Taiwanese only, six-in-ten (61%) said that they, and at least one of their parents, were born in Taiwan. On the other hand, out of the 227 people who said they were born in Taiwan, just over one-third (37%) said they strictly identified as being Taiwanese, while about one-in-ten (11%) reported being both Taiwanese and Chinese.

How does our classification of the sample impact our analysis of the responses?

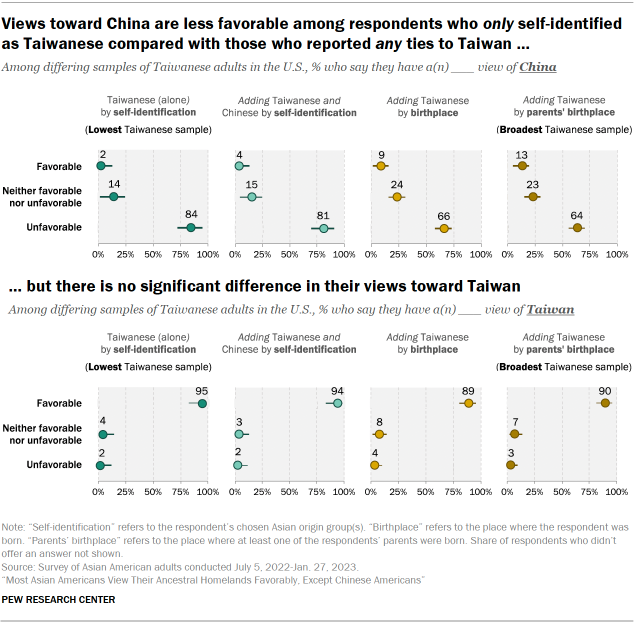

When analyzing responses based on these different groups, significant differences exist in attitudes between the smallest subset of the Taiwanese sample that includes those who explicitly self-identified as being Taiwanese alone (which is the one used in the report); the broader subset that includes those who have self-identified as Taiwanese in addition to Chinese; an even broader subset that also includes those who reported Taiwan as a birthplace; and finally the broadest subset that also includes those who reported Taiwan as a parents’ birthplace.

For example, when questioned about their views of China, a very large majority (84%) of those who identify as Taiwanese alone report an unfavorable opinion toward the country. Meanwhile, those who have any ties to Taiwan – whether by identity, birthplace or parents’ birthplace – still have broadly negative views of China, but the share who hold this opinion is markedly smaller (64%). The shares who hold favorable views toward China are not significantly lower among the sample of respondents who only identified as Taiwanese, compared with the sample that also includes those who reported broader ties to Taiwan.

Attitudes do not always differ significantly between the different subsets of the sample, however. For example, huge majorities across all groups (89% or higher) hold favorable views toward Taiwan.

The issues that we have highlighted in this section reflect the larger challenge behind the task of measuring various forms of identities in social science research. Identity, by its nature, is nuanced and subject to the lens of different cultures and communities that it is examined through. The various methods for defining Taiwanese identity that we have outlined in this section present just one example of how a single identity can inspire numerous definitions and present sincere research challenges. This also brings attention to how data disaggregation can help us understand attitudes and opinions within subgroups.

This appendix was written by temporary Research Associate Abby Budiman in addition to the co-authors of this report.