In a number of countries with sizable Muslim and Jewish populations, we asked Muslim and Jewish adults for their views on religion and governance – specifically, whether religious law should be the official or state law for people who share their religion, and whether their country can be both a democratic country and a Muslim or Jewish country.

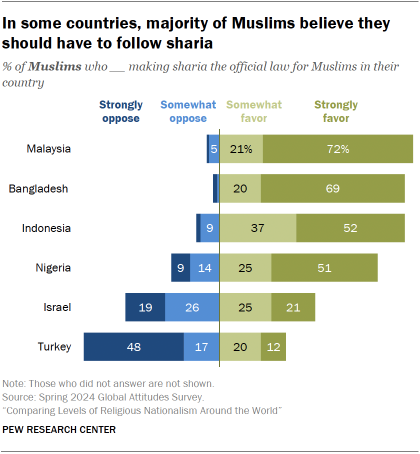

We find that large majorities of Muslims in Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia and Nigeria believe sharia, or Islamic law, should be the official law for Muslims in their country. Much smaller shares of Muslims in Israel and Turkey agree.

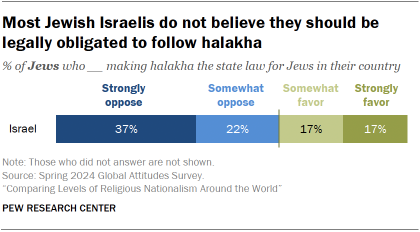

Among Israelis who are Jewish, about a third support making halakha, or Jewish law, the state law for Jews in Israel.

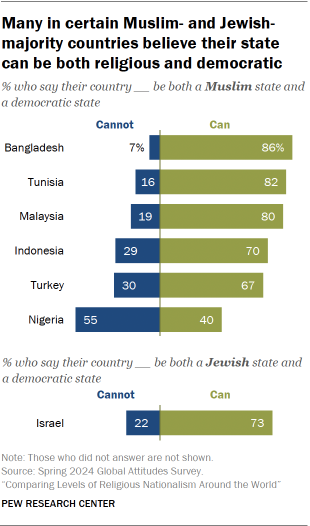

When it comes to whether states can have a religious character and be a democracy:

- Majorities of Bangladeshis, Indonesians, Malaysians, Tunisians and Turks say their country can be both a democracy and a Muslim state.

- A minority of Nigerians think Nigeria can be both democratic and Muslim.

- A majority of Israelis think Israel can be both democratic and Jewish – though Jewish Israelis are more than twice as likely as Muslim Israelis to say this.

Should Muslims be governed by sharia?

Support for Islamic religious law, also known as sharia, is widespread in several of the Muslim-majority countries surveyed.

Sharia, or Islamic law, offers moral and legal guidance for nearly all aspects of life for Muslims, from marriage and divorce, to inheritance, contracts and criminal punishments. Sharia in its broadest definition refers to the ethical principles set down in Islam’s holy book (the Quran) and by examples of actions by the Prophet Muhammad (sunna). The Islamic jurisprudence that comes out of the human exercise of codifying and interpreting these principles is known as fiqh. Muslim scholars and jurists continue to debate the boundary between sharia and fiqh as well as other aspects of Islamic law.

About nine-in-ten Muslims in Bangladesh, Indonesia and Malaysia say they favor a legal system in which Muslims are bound by Islamic law. Roughly three-quarters of Nigerian Muslims agree. At least half of Muslims in each of these countries say they strongly favor making sharia the official law for those who share their religion.

Israeli Muslims, who make up about a fifth of their country’s population, are evenly split on the question: 46% favor making sharia the official law for Muslims in Israel, while 45% oppose this. An additional 9% did not answer the question.

Over 90% of Turkey’s population is Muslim. Yet only about a third of Turkish Muslims (32%) favor granting official status to Islamic law. Almost half – a 48% plurality – say they strongly oppose making sharia the law for Muslims in their country.

Support for making sharia the official law for Muslims is somewhat correlated with religiousness. Muslim populations with higher rates of daily prayer are more in favor of making sharia the law for Muslims in their country. For example, among Malaysian Muslims, 90% say they pray at least daily, and 93% are in favor of making sharia the official law. Meanwhile, in Israel, 58% of Muslims pray at least daily, and 46% support sharia.

Among Muslims in Israel and Turkey, opinions vary by age. In both countries, Muslims ages 50 and older are more likely than those ages 18 to 34 to favor making sharia the official law for Muslims.

In Turkey, about four-in-ten adults with lower levels of education believe sharia should be the law for Muslims. Only 22% of Turks with higher levels of education agree.

Also in Turkey, Muslim supporters of the governing Justice and Development Party are more than twice as likely as Muslims who don’t support the party to favor a legal system based on sharia (55% vs. 20%).

(For more on religion and governance in Turkey, read our October report: “Turks Lean Negative on Erdoğan, Give National Government Mixed Ratings”)

Should halakha be the law for Jews?

In Israel, the world’s only majority-Jewish country, we asked Jews whether halakha – the traditional set of rules and regulations that govern Jewish life – should be the state law for people who share their religion.

Halakha, or Jewish law, refers to the set of rules and practices that govern Jewish life. They originate from the Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible), the Oral Torah, other Jewish scripture and their interpretations by Jewish scholars over the years. There are halakhic laws to regulate how Jews pray, celebrate holidays, work, eat, dress and conduct their relationships with other Jews and non-Jews. Attitudes towards halakha generally follow the spectrum of religious observance: Haredim and other Orthodox Jews consider it essential to follow these rules, while less religious Jews tend to oppose enforcing halakha.

About a third of Israeli Jews say they favor a legal system for Jews based on Jewish law, while six-in-ten or so oppose such a system. A plurality of 37% strongly oppose being legally bound by halakha.

Jews in Israel differ significantly in their views of halakha:

- Haredi (“ultra-Orthodox”) and Dati (“religious”) Jews are significantly more likely to favor making halakha the official law for Jews in Israel than either Masorti (“traditional”) Jews or Hiloni (“secular”) Jews. About nine-in-ten Haredi and Dati Jews express this opinion, while 20% of Masorti Jews and 4% of Hiloni Jews agree. Haredim and Datiim, as well as Hilonim, feel strongly on the subject: Half of Haredim and Datiim strongly favor a legal system for Jews based on Jewish law, while 70% of Hilonim strongly oppose this.

- Similarly, more than eight-in-ten Israeli Jews who pray at least daily say halakha should be the law for Jews in Israel. Only 13% of Jews who pray less often express this opinion.

- Younger Jews (ages 18 to 34) are twice as likely as Jews ages 50 and older to say they strongly favor making halakha the official law for Jews in Israel (24% vs. 12%).

- Only a quarter of Israeli Jews with a postsecondary education favor making halakha the state law for Jews. Among Jews with a secondary education or less, the share who agree is much higher, at 43%.

Can a country be both religious and democratic?

In countries with Muslim majorities, most do think their state can be both democratic and Muslim. The shares saying this are particularly high in Bangladesh (86%), Tunisia (82%) and Malaysia (80%). (Islam is the official state religion in Bangladesh and Malaysia, and it was the official religion in Tunisia until 2022).

Slightly smaller majorities in Indonesia (70%) and Turkey (67%) agree that their country can be both a Muslim state and a democratic state at the same time.

Of the countries where we asked this question, Nigeria is the only one in which Muslims are not the overwhelming majority of the population. Only 40% of Nigerians say Nigeria can be both Muslim and democratic – roughly half the shares expressing this opinion in Bangladesh, Malaysia and Tunisia. A slim majority of Nigerians (55%) say it cannot be both.

Over half of Nigerian Muslims (55%) say their country can be Muslim and democratic at the same time, while about a third of Nigerian Christians (31%) agree.

Views on the subject also differ by religiousness and education in a few countries surveyed:

- In Malaysia, Nigeria and Turkey, people who pray at least daily are more likely than those who pray less often to say their country can be both Muslim and democratic. (However, Nigerians who pray daily are also more likely than other Nigerians to answer the question.)

- Tunisians and Indonesians with less than a secondary education are more likely than those with more education to say their country can be both Muslim and democratic.

Can Israel be both democratic and Jewish?

Israel defines itself as “Jewish and democratic,” and indeed, 73% of adults surveyed in Israel say their country can be both. Only about two-in-ten Israelis say the country cannot be a Jewish state and a democratic state at the same time. Still, there are some significant differences on this question by religion and political ideology.

- Israeli Jews are more than twice as likely as Israeli Muslims to say their country can be both Jewish and democratic (82% vs. 38%).

- Among Jewish religious groups, Masortim are the most likely to say Israel can be Jewish and democratic at the same time (93%). Smaller majorities of Haredim/Datiim (81%) and Hilonim (77%) agree.

- Israelis who place themselves on the ideological right (84%) and in the center (77%) are significantly more likely than Israelis on the left (48%) to say their country can be both Jewish and a democracy.

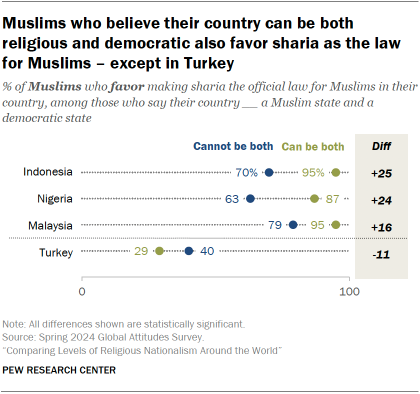

How people who believe their country can be both religious and democratic differ in their views

In some countries, attitudes toward religious texts and laws vary based on whether one thinks a country can be a Muslim or Jewish state and a democracy at the same time.

- In Malaysia, those who believe their country can be both Muslim and democratic are 18 points more likely than those who say it cannot to think the Quran should influence Malaysian law a great deal (65% vs. 47%). Similar differences exist between these groups in Indonesia and Nigeria.

- Indonesians and Nigerians who believe their country can be Muslim and democratic are also more likely to say the Quran currently has a great deal of influence on the law in their country.

- Among Israelis who say their country can be both Jewish and democratic, 45% say Jewish scripture should influence the law in Israel. Among those who say Israel cannot be both a democracy and a Jewish state, fewer than a third (29%) agree.

Muslims in Indonesia, Malaysia and Nigeria who say their country can be Muslim and democratic at the same time are more likely than Muslims who say otherwise to support making sharia the law for those who share their religion.

In Turkey, the opposite is true: Muslim Turks who say their country can be both Muslim and democratic are less likely than those who say it cannot to favor sharia (29% vs. 40%).