This report examines cross-national perceptions of science and its place in society along with attitudes on a number of science-related issues.

Data in this report come from a survey conducted across 20 publics from October 2019 to March 2020 across Europe, Russia, the Americas and the Asia-Pacific region. The surveys were conducted by face-to-face interviews in Russia, Poland, the Czech Republic, India and Brazil. In all other places, the surveys were conducted by telephone. All surveys were conducted with representative samples of adults ages 18 and older in each survey public.

Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

As publics around the world look to scientists and the research and development process to bring new treatments and preventive strategies for the novel coronavirus, a new international survey finds scientists and their research are widely viewed in a positive light across global publics, and large majorities believe government investments in scientific research yield benefits for society.

Still, the wide-ranging survey, conducted before the COVID-19 outbreak reached pandemic proportions, reveals ambivalence about certain scientific developments – in areas such as artificial intelligence and genetically modified foods – often exists alongside high trust for scientists generally and positive views in other areas such as space exploration.

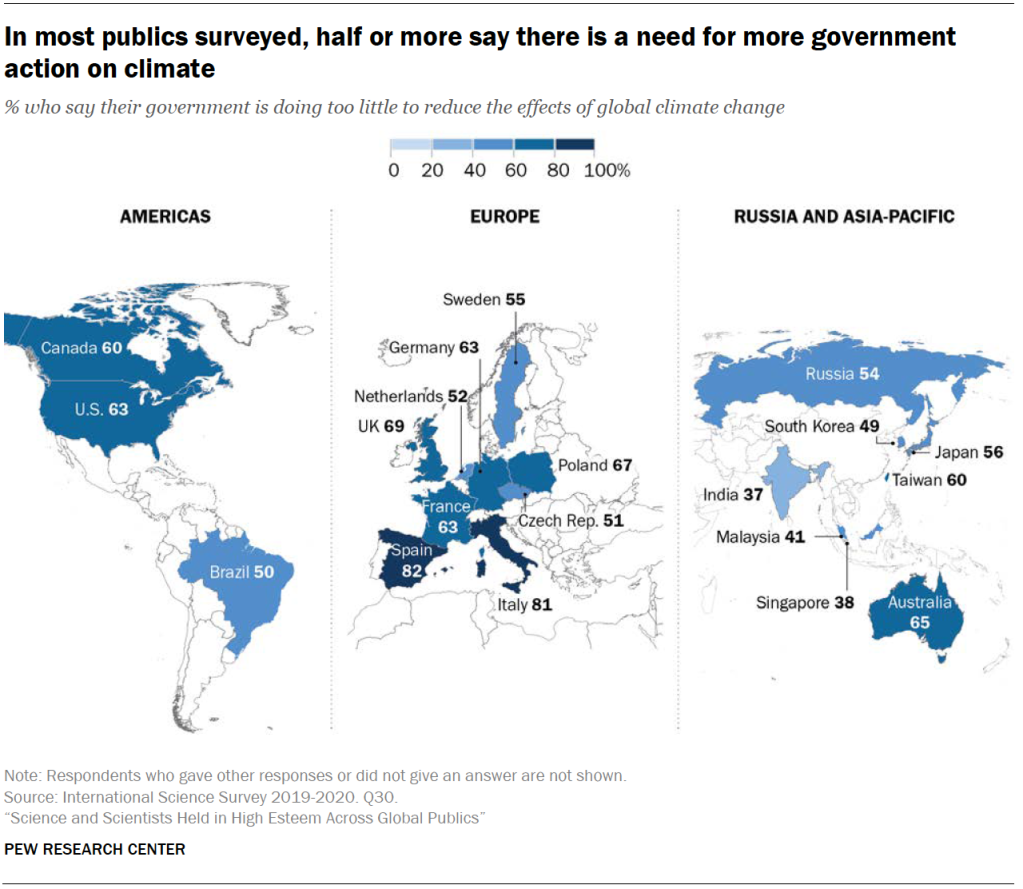

Public concerns around climate change and environmental degradation remain widespread. In most publics, majorities view climate change as a very serious problem, say their government is not doing enough to address it and point to a host of environmental concerns at home, including air and water quality and pollution.

With renewed attention to the importance of public acceptance of vaccines, the new survey finds majorities in most publics tend to view childhood vaccines, such as those for measles, mumps and rubella, as relatively safe and effective. Yet sizable minorities across global publics hold doubts about this keystone tool of modern medicine.

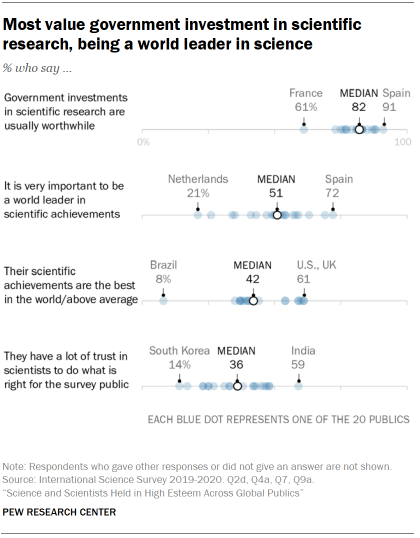

The international survey, fielded in publics across Europe, the Asia-Pacific region, and in the United States, Canada, Brazil and Russia finds broad agreement about the value of scientific research. A median of 82% consider government investment in scientific research worthwhile, and majorities across places view it as important to be a leader in scientific achievements.

The Center survey sheds light on how publics see the place of science in society amid the changing global landscape for scientific research and innovation. The U.S. had the largest share of global spending on research and development in the past, but recent years have seen greater investments by Taiwan, South Korea and mainland China. China is expected to equal or exceed the U.S. in global R&D investments in the coming years, according to data collected by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.1

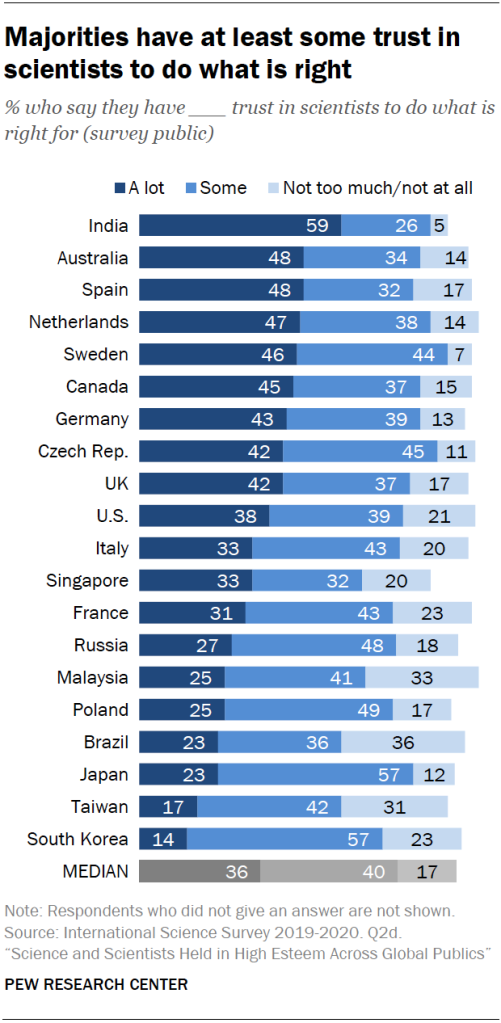

Scientists as a group are highly regarded, compared with other prominent groups and institutions in society. In all publics, majorities have at least some trust in scientists to do what is right. A median of 36% have “a lot” of trust in scientists, the same share who say this about the military, and much higher than the shares who say this about business leaders, the national government and the news media.

Still, an appreciation for practical experience, more so than expertise, in general, runs deep across publics. A median of 66% say it’s better to rely on people with practical experience to solve pressing problems, while a median of 28% say it’s better to rely on people who are considered experts about the problems, even if they don’t have much practical experience.

The publics’ assessments of their own achievements in science do not always measure up to their aspirations: A median of 42% say their scientific achievements are above average or the best in the world. However, the shares holding this view ranges from 8% in Brazil to 61% each in the U.S. and United Kingdom.

And in many places, the public sees room for improvement when it comes to education at the university or primary and secondary school levels in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). A median of 42% rate university STEM education in their survey public as above average or the best in the world, and a smaller median of 30% give high marks to their science, technology, engineering and math education at the primary and secondary school level.

These are among the chief findings from the survey conducted among 20 publics with sizable or growing investments in scientific and technological development from across Europe (the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom), the Asia-Pacific region (Australia, India, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan) as well as Russia, the United States, Canada and Brazil.

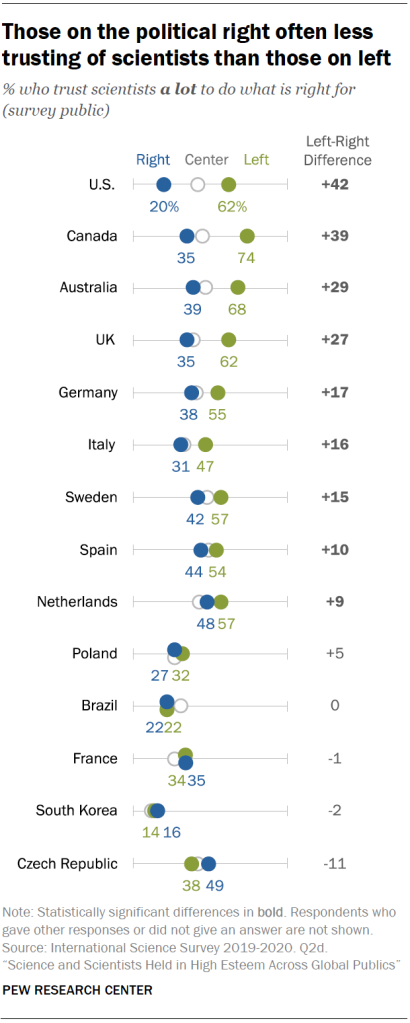

Public trust in scientists is often higher for those on the left than the right of the political spectrum

While there is generally a positive tilt toward public trust in scientists, trust often varies with ideology. In general, those on the left express more trust in scientists than those on the right.

Such differences are especially pronounced in the U.S., where fully 62% of those on the left have a lot of trust in scientists, compared with two-in-ten of those on the right. (The gap is similar factoring in party identification; 67% of liberal Democrats in the U.S. say they have a lot of trust in scientists, compared with 17% of conservative Republicans.)

Left-right divides are also present in a number of other places. In Canada, for instance, 74% of those who place themselves on the left say they have a lot of trust in scientists to do what is right, compared with 35% of Canadians with right-leaning political views.

In the UK, there’s a 27 percentage point difference between the shares of those on the left and right who have a lot of trust in scientists. Germany (by 17 points), Sweden (15 points) and Spain (10 points) are among the other places where those on the left are more trusting of scientists than those on the right.

Consistent with this ideological pattern, those with favorable views of right-wing populist parties in Europe tend to express lower levels of trust in scientists than those with unfavorable views of these parties.

However, differences by political ideology do not strongly extend to other views of scientists or experts. For instance, there are generally modest or no left-right differences in views of whether scientists tend to make judgments based solely on the facts or are just as likely to be biased as other people. And in most places, there’s general agreement across the political spectrum that, when it comes to solving pressing problems, it is better to rely on people with practical experience than on people with expertise. A median of two-thirds say it is better to rely on people with practical experience, while a median of 28% say it is better to rely on people with expertise, even if they don’t have practical experience.

Amid rising concern about global climate change, most see at least some impact from climate change where they live and say their government is doing too little to address it

International concern about climate change has increased over the past several years, with growing shares viewing climate change as a major threat. In addition, large majorities in the current survey express worry over climate change and describe it as a serious problem.

A median of seven-in-ten across the set of 20 publics say climate change is having at least some effect on their local community. And in some places – Italy, Spain and Brazil – about half or more see a great deal of impact from climate change in their community. Government action on climate change is widely seen as lacking: Majorities across most of surveyed publics believe their government is doing too little to address climate change (20-public median of 58%).

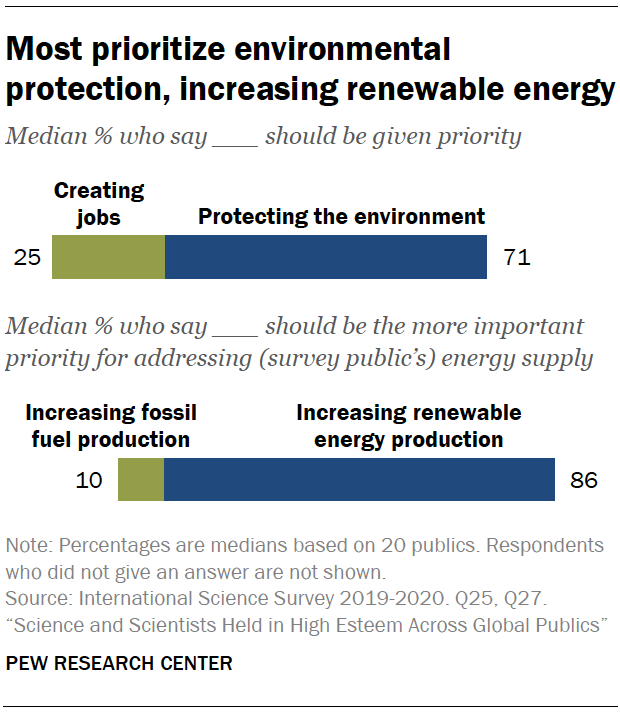

Across the 20 publics surveyed, environmental concerns extend beyond the issue of climate change: Large majorities rate a host of environmental issues as big problems, including air and water pollution, overburdened landfills, deforestation and the loss of plant and animal species. In general terms, environmental concerns trump economic considerations: When asked to choose, a median of 71% said environmental protection should be the greater priority even if it caused slower economic growth and loss of jobs; a much smaller median of 25% said creating jobs should be the priority (the survey was conducted before the coronavirus pandemic and resultant economic strains took hold in many of these publics).

Consistent with environmental worries, majorities across all 20 publics say the more important energy priority should be increasing production of renewable energy such as wind and solar sources over increasing production of oil, natural gas and coal (median of 86% to 10%). Views about specific energy sources underscore this pattern with strong majorities in favor of expanding the use of wind, solar and hydropower sources and much less support, by comparison, for energy sources such as oil or coal. Views on expanding natural gas fall somewhere in between.

Public views about climate, environment and energy issues are strongly linked with political ideology. For example, those who place themselves on the political left are more inclined to see climate change as a serious problem and to think their government is doing too little to address it than those on the right; these differences are particularly wide in the U.S., Australia, Sweden, Canada, the UK and the Netherlands.

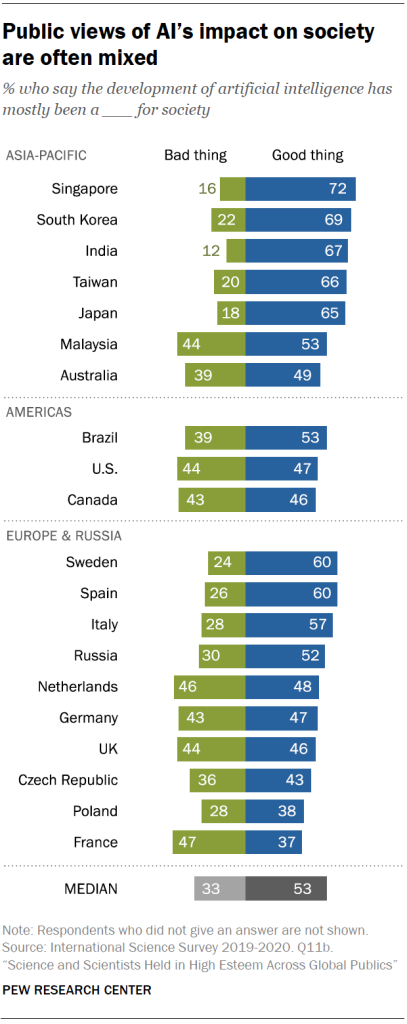

There is little consensus across regions in views of artificial intelligence, automation in the workplace

Public views of artificial intelligence, described for survey respondents as computer systems designed to imitate human behaviors, are generally viewed positively by publics in the Asia-Pacific region. A median of two-thirds in the Asia-Pacific say that AI has been a good thing for society, while a median of 20% say it has been a bad thing. Elsewhere public views are mixed. In Europe a median of 47% say the development of AI has been good for society. Roughly half view AI positively in Brazil (53%), Russia (52%), the U.S. (47%) and Canada (46%).

Opinions about the impact of robotics to automate jobs also are mixed. A median of 48% say such automation has mostly been a good thing, while 42% say it has been a bad thing. As with views of AI, assessments of job automation are generally more positive in the Asia-Pacific region (median of 61% say it’s been a good thing). Fewer in Europe (a median of 48%) share this positive view. Those in France (35%), Spain (37%) and Brazil (29%) are among the least likely to say robots and automation in the workplace has been a good thing for society. In the U.S., slightly more say this type of automation has been bad than good for the country (50% vs. 41%).

Across places surveyed, those with higher levels of education and who have taken more science courses in their schooling are especially likely to consider AI and workplace automation as a positive development for society. Views tend to be less positive among those with lower levels of education.

Many publics give positive marks for handling the coronavirus outbreak

The coronavirus pandemic altered the lives of people around the world. Governments applied a myriad of approaches in response to the outbreak, and the scope of the health crisis varied widely.

A separate Pew Research Center survey conducted June to August of 2020 in 14 countries found a median of 73% think their country has done a good job handling the novel coronavirus. Strong majorities in Denmark, Germany, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands and South Korea hold this view as do at least seven-in-ten in Italy and Sweden. In Japan 55% give their country positive marks. In the UK, U.S. and Spain, ratings are more divided, with wide differences of opinion across political or ideological groups about their country’s handling of the outbreak.

More think their country has done a bad job handling the outbreak in places with higher counts of coronavirus-related fatalities. Similarly, the share who say their country is more divided than before the outbreak is strongly related to the number of cases and deaths from the disease. The U.S. stands out on this measure with 77% of Americans saying the outbreak has further divided the nation.

Among the reports’ other major findings:

- Many see childhood vaccines as bringing high preventive health benefits but some doubts about safety and effectiveness remain. A majority of adults in 17 of the 20 publics rate the preventive health benefits from childhood vaccines – such as the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine – to be high. But there are only a handful of publics – Sweden, Spain and Australia – where about eight-in-ten or more are convinced of the high preventive health benefits. Smaller majorities take this view in other places, including Italy, the Netherlands and Singapore. And while most places consider the risk of side effects from childhood vaccines to be low, half or more in Japan, Malaysia, Russia, South Korea, France and Singapore consider the risk to be medium or high. Those who identify on the political right, or who have a favorable view of a right-wing populist party in Europe, are less likely to see the preventive health benefits of such vaccines as high or the risk of side effects to be low or none. These differences are particularly large in the Netherlands, UK and France.

- There are widespread concerns about the safety of genetically modified foods in many of these publics. Larger shares believe foods with genetically modified (GM) ingredients are unsafe to eat than say they are safe (20-public median of 48% vs. 13%). Though familiarity with GM foods is not always high: A median of 37% say they don’t know enough about such foods to say. Health risks also are seen in produce grown with pesticides and food and drinks with artificial preservatives. Women are more likely than men to express safety concerns about all three food groups.

- Many give science news coverage positive marks but cite lack of public understanding as a problem for science coverage. Overall, a median of 68% say the news media do a very or somewhat good job covering science; 28% say they generally do a bad job. Publics generally agree about one issue with the news, however: Majorities across 18 of the 20 publics say that limited public understanding is a problem for coverage of scientific research. Far fewer consider media oversimplifying findings or researchers overstating their findings to be a problem for coverage of research.