The presidential nomination contests are heating up and both parties’ 2016 fields have narrowed. And since it’s also Presidents Day weekend, it’s a good time to consider what voters want in a president, regardless of which candidate they may support.

Past experience is not necessarily required (especially for Republicans).

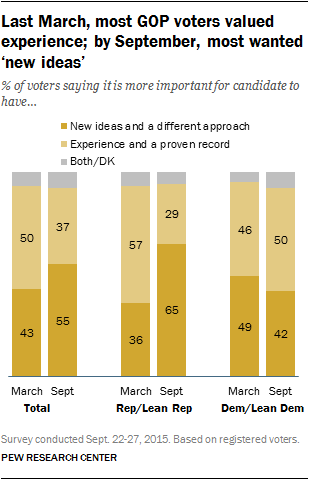

Last March, more than a year before the first primaries, more voters valued a hypothetical candidate with “experience and a proven record” (50%) than one who had “new ideas and a different approach” (43%). Just six months later, those numbers had flipped – 55% said it was more important for a candidate to have new ideas, while 37% valued experience and a proven record.

This shift came entirely among Republican and Republican-leaning voters. The share of Republicans saying it was more important for a candidate to have new ideas increased by nearly 30 percentage points over this period, from 36% to 65%. Opinions among Democratic voters remained far more stable. In September, 50% valued experience, about the same as the 46% who said this in March.

Past experience as a Washington lawmaker also is viewed more negatively among the public overall than in prior presidential campaigns – again, especially among Republicans. In January, 31% of the public – including 44% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents – said they would be less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who had been an elected official in Washington for many years. In 2007, just 15% of the public and 20% of Republicans had a negative view of a candidate with longtime experience as a D.C. elected official.

Military experience is preferred, but increasingly rare.

While the public continues to view military experience very positively, it is a trait that none of the top remaining 2016 candidates possesses. In a survey last month, 50% of Americans said they would be more likely to vote for a presidential candidate who has served in the military – the most positively viewed trait among 13 tested. In the prior two presidential campaigns, military experience also was viewed very positively.

The 2012 election was the first in more than 80 years in which neither of the major party presidential candidates had served in the military. But this may not be surprising given that military veterans make up steadily declining shares of both the public and members of Congress.

Support is limited for a candidate who does not believe in God.

In our recent survey on faith and the 2016 campaign, large majorities of Americans said it would make no difference to them if a presidential candidate were Jewish (80%) or Catholic (75%). Being an evangelical Christian also is a neutral characteristic; 55% of U.S. adults said it wouldn’t matter if a candidate were an evangelical, while similar shares said it would make them more likely (22%) or less likely (20%) to vote for that person.

Members of certain other religious groups, however, may have a harder time reaching the White House because of their religious beliefs. While 69% of Americans said it wouldn’t matter if a candidate were a Mormon, 23% said they would be less likely to vote for a Mormon. Even more had a negative view of a hypothetical Muslim candidate: 42% said they would be less likely to support such a candidate, while 53% said it would make no difference.

Not believing in God remains an even greater potential liability for a candidate. About half of Americans (51%) said they would be less likely to vote for an atheist candidate, though this share has fallen from 63% in 2007.

For most voters, “electability” matters less than issue positions.

Political pundits often focus on the “electability” of candidates – how they might fare in a general election contest. But in September, majorities of voters in both parties said it was more important for a candidate to share their positions on the issues.

Two-thirds of both Republican (67%) and Democratic (65%) registered voters said it was more important for a candidate to share their positions on issues than it was for a candidate to have the best chance of defeating the other party’s nominee.