The Supreme Court today voided a key provision of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, meaning several states and local jurisdictions no longer have to get federal approval for changes to their voting laws and procedures.

The 5-4 opinion, written by Chief Justice Roberts, didn’t strike down the “preclearance” provision of the law itself, but rather the decades-old formula used to determine which states and localities fall under it. Currently, all or most of nine states are covered by the preclearance rule, as are local jurisdictions in six other states.

The ruling didn’t affect the law’s general prohibition against any voting rule or practice that “results in a denial or abridgement of the right of any citizen…to vote on account of race or color.” But any such practices would have to be challenged individually, unless Congress can agree on a new coverage formula — something most observers consider unlikely.

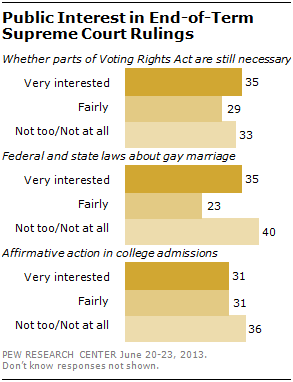

The ruling has been one of the most anticipated of the Court’s term. A new Pew Research Center survey found that 35% of the public said they were “very interested” in how the Court would rule — about as many as expressed that level of interest in two pending same-sex marriage cases and in Monday’s affirmative-action decision.

That degree of interest in voting-law cases is nothing new. Back in June 2009, as the Senate was considering Sonia Sotomayor’s nomination to the Court, a Pew Research survey found that 57% of people said Court decisions on election and voting rules were “very important” to them personally, and 25% said they were “fairly important” — about the same as the responses for abortion and the rights of terrorism suspects, and well ahead of affirmative actions and issues related to homosexuality.

There’s been relatively little polling specifically on the Voting Rights Act, but what there is shows a closely divided public. In a recent New York Times/CBS News poll, 49% of Americans said the act is necessary to ensure that blacks can vote, but 44% said it was not necessary. Blacks (75%) and Democrats (59%) were far more likely to say the act was still needed than whites (46%), independents (48%) or Republicans (36%).

Voting and elections data can be interpreted to support either position. Andrew Kohut, founding director of the Pew Research Center, wrote in a recent Wall Street Journal op-ed piece that few Americans of any race reported having problems or difficulties in voting this past November: 4% of whites and 2% of blacks, in a Pew Research poll taken just after the election. And a Census survey found, on average, slightly higher reports of voting among African-Americans than among whites in former Confederate states, 67% to 62%.

Opponents of the preclearance requirement, Kohut continued, “can point to these surveys to show that the racial gap in voting has dramatically diminished, and has arguably disappeared. The legislation has accomplished its objective of ending racial discrimination in voting and is no longer needed. But those who oppose change can counter that it is unwise to change laws that have made such important difference in the workings of democracy.”