The Growing Partisan Divide in Views of Higher Education

Americans see value in higher education – whether they graduated from college or not. Most say a college degree is important, if not essential, in helping a young person succeed in the world, and college graduates themselves say their degree helped them grow and develop the skills they needed for the workplace. While fewer than half of today’s young adults are enrolled in a two-year or four-year college, the share has risen steadily over the past several decades. And the economic advantages college graduates have over those without a degree are clear and growing.

Even so, there is an undercurrent of dissatisfaction – even suspicion – among the public about the role colleges play in society, the way admissions decisions are made and the extent to which free speech is constrained on college campuses. And these views are increasingly linked to partisanship.

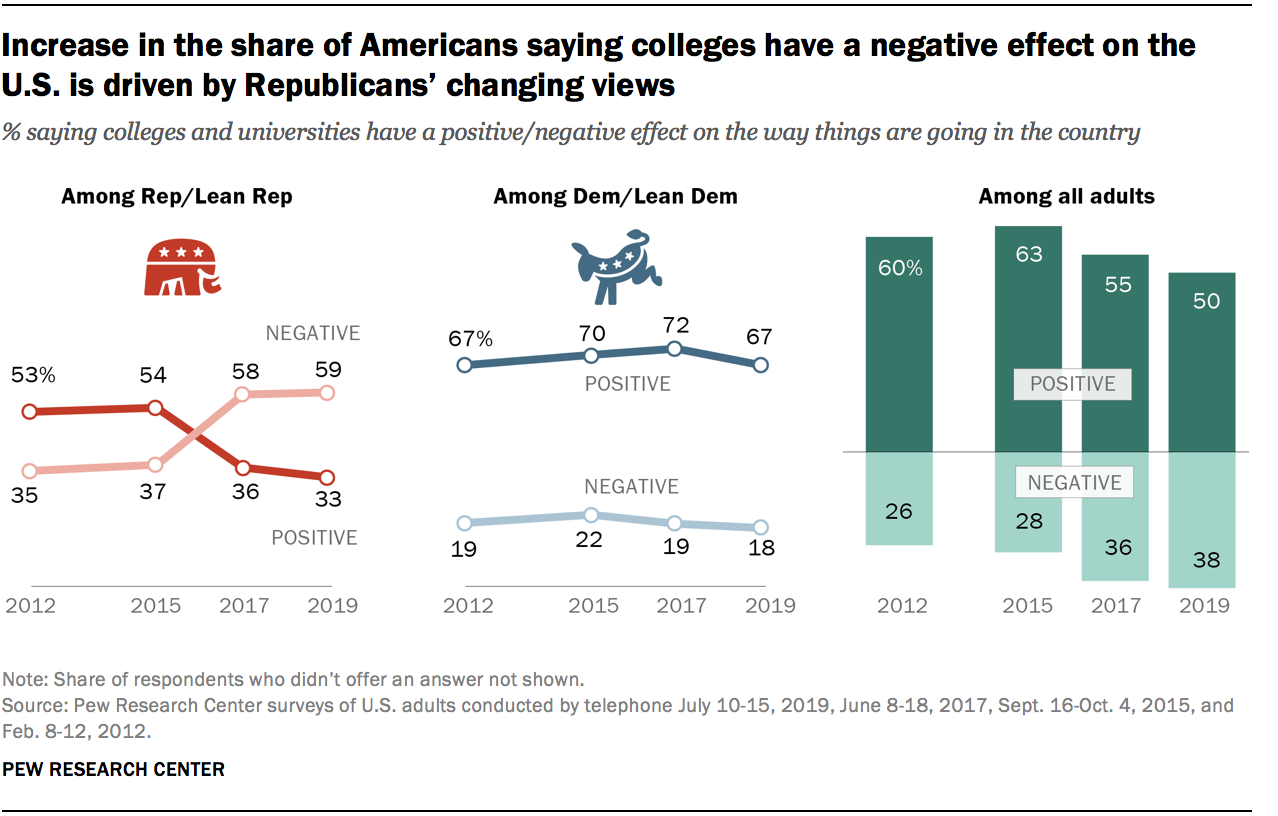

A new Pew Research Center survey finds that only half of American adults think colleges and universities are having a positive effect on the way things are going in the country these days. About four-in-ten (38%) say they are having a negative impact – up from 26% in 2012.

The share of Americans saying colleges and universities have a negative effect has increased by 12 percentage points since 2012. The increase in negative views has come almost entirely from Republicans and independents who lean Republican. From 2015 to 2019, the share saying colleges have a negative effect on the country went from 37% to 59% among this group. Over that same period, the views of Democrats and independents who lean Democratic have remained largely stable and overwhelmingly positive.

Gallup found a similar shift in views about higher education. Between 2015 and 2018, the share of Americans saying they had a great deal or quite a lot of confidence in higher education dropped from 57% to 48%, and the falloff was greater among Republicans (from 56% to 39%) than among Democrats (68% to 62%).1

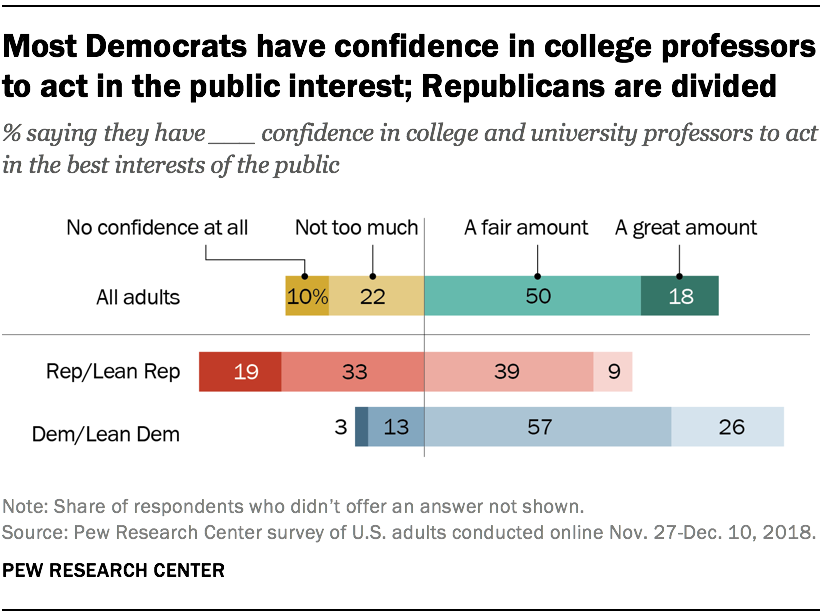

Two additional Pew Research Center surveys underscore the partisan gap in views about higher education. In late 2018, 84% of Democrats and independents who lean to the Democratic Party said they have a great deal or a fair amount of confidence in college and university professors to act in the best interests of the public. Only about half (48%) of Republicans and Republican leaners said the same. In fact, 19% of Republicans said they have no confidence at all in college professors to act in the public interest. And in early 2019, 87% of Democrats – but fewer than half (44%) of Republicans – said colleges and universities are open to a wide range of opinions and viewpoints.

Republicans and Democrats differ over what’s ailing higher education

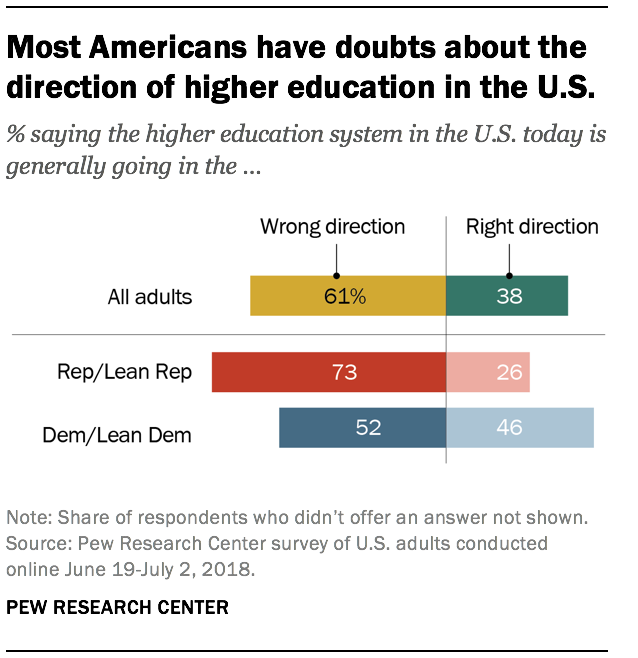

A 2018 Pew Research Center survey took a deeper dive into the reasons for these shifting views. The survey first asked whether the higher education system in the U.S. is generally going in the right or wrong direction. A majority of Americans (61%) say it’s going in the wrong direction. Republicans and Republican leaners are significantly more likely to express this view than Democrats and Democratic leaners (73% vs. 52%).

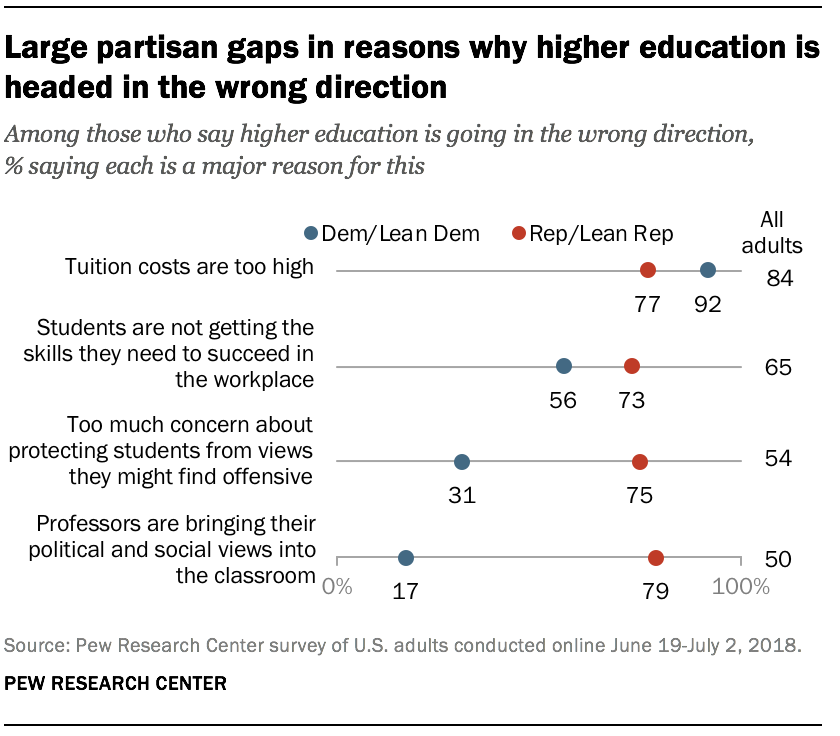

Among those who say higher education is headed in the wrong direction, some of the reasons why they think this is the case differ along party lines. Majorities of Republicans (77%) and Democrats (92%) say high tuition costs are a major reason why they believe colleges and universities are headed in the wrong direction.

Democrats who see problems with the higher education system cite rising costs more often than other factors as a major reason for their concern, while Republicans are just as likely to point to other issues as reasons for their discontent. Roughly eight-in-ten Republicans (79%) say professors bringing their political and social views into the classroom is a major reason why the higher education system is headed in the wrong direction (only 17% of Democrats say the same). And three-quarters of Republicans (vs. 31% of Democrats) point to too much concern about protecting students from views they might find offensive as a major reason for their views. In addition, Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say students not getting the skills they need to succeed in the workplace is a major reason why the higher education system is headed in the wrong direction (73% vs. 56%).

There are significant age gaps among Republicans in these views. Older Republicans are much more likely than their younger counterparts to point to ideological factors, such as professors bringing their views into the classroom and too much concern about political correctness on campus. For example, 96% of Republicans ages 65 and older who think higher education is headed in the wrong direction say professors bringing their views into the classroom is a major reason for this. Only 58% of Republicans ages 18 to 34 share that view.

A 2017 Gallup survey found similar partisan divides when it asked those who expressed only some or very little confidence in U.S. colleges and universities why they felt that way. Democrats tended to focus more on costs and quality, with 36% volunteering that college is too expensive, 14% saying colleges have poor leadership and are not well run, and 11% saying the overall quality of higher education is going down. Republicans focused more on political and ideological factors: 32% said colleges and universities are too political or too liberal (only 1% of Democrats volunteered this type of response). And 21% of Republicans pointed to colleges not allowing students to think for themselves and pushing their own agenda as reasons why they didn’t have a lot of confidence in them.

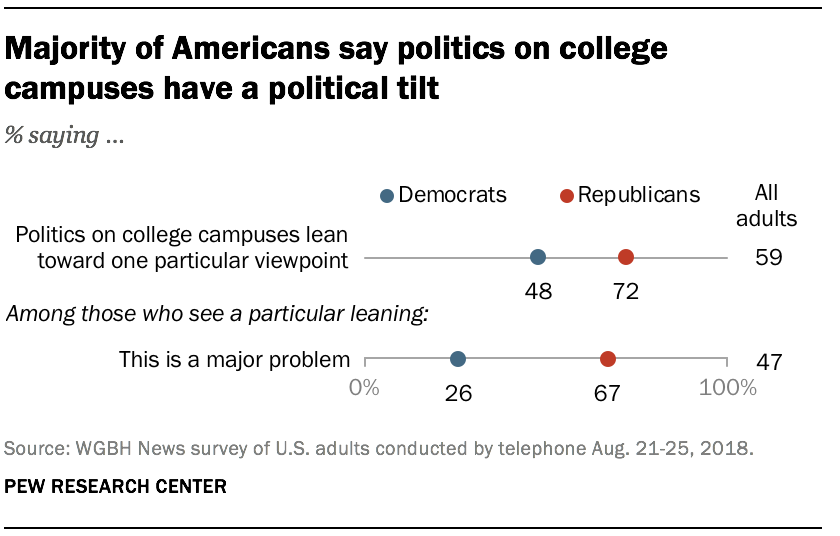

Another national survey conducted last year by Boston-based WGBH News looked more closely at views about the political climate at colleges and universities. A majority of adults (59%) said politics on college campuses lean toward a particular viewpoint, while 28% said campuses are nonpartisan. Of those who thought politics lean toward one particular viewpoint, 77% said they lean liberal, while 15% said they lean conservative. About half (47%) of those who see an ideological tilt at colleges and universities said this is a major problem, while 32% said it’s a minor problem.

These views differed substantially by party. A majority of Democrats (60%) said students are hearing a full range of viewpoints on college campuses, but only 26% of Republicans shared that view.2 In addition, Republicans were much more likely than Democrats to see a political leaning on college campuses: 72% of Republicans compared with 48% of Democrats said campuses lean toward one particular viewpoint. Among those who saw a political leaning, majorities of Republicans (85%) and Democrats (68%) said campuses lean more liberal than conservative. But Republicans were much more likely than Democrats to say that campuses leaning toward a particular viewpoint is a major problem – 67% of Republicans vs. 26% Democrats said this.

Views on the college admissions process

The equity of the college admissions process has come into question recently, with many concerned that wealth and privilege are having an undue influence. Earlier this year, the College Board announced that it will begin including an “adversity score” along with a student’s SAT score in an effort to provide more information about students’ educational and socioeconomic backgrounds.

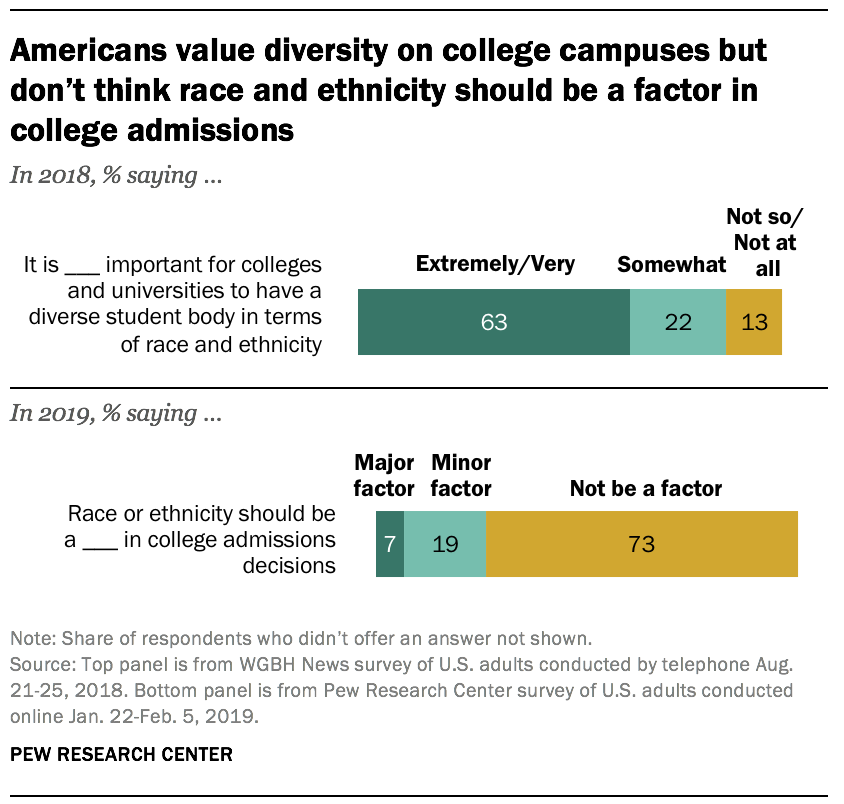

According to the WGBH News survey, the vast majority of Americans say it’s important for colleges and universities to have a diverse student body in terms of race and ethnicity. About six-in-ten (63%) say this is extremely or very important and an additional 22% say it’s somewhat important. Only 13% say diversity on campuses is not important.

However, a recent Pew Research Center survey finds that the public is not in favor of colleges and universities considering race or ethnicity in making admissions decisions. Some 73% of all adults say race or ethnicity should not be a factor in college admissions decisions. About one-in-five (19%) say this should be a minor factor and 7% say it should be a major factor. Majorities across racial and ethnic groups – 62% of blacks, 65% of Hispanics, 58% of Asians and 78% of whites – say race and ethnicity should not be a factor in admissions decisions. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say race and ethnicity shouldn’t be a factor in admissions decisions, but majorities of both groups express this view (85% among Republicans, 63% among Democrats).

So what factors does the public think should drive admissions decisions? High school grades top the list – 67% say grades should be a major factor in making these decisions, and 26% say they should be a minor factor. About half (47%) say standardized test scores should be a major factor, and 41% say they should be a minor factor.

Those two largely objective factors stand out among other potential admissions criteria. Fewer adults say community service involvement (21% cite this as a major factor, 48% minor) or being a first-generation college student (20% major, 27% minor) should be factors in making college admissions decisions. And fewer still say that athletic ability (8% major, 34% minor) or legacy status (8% major, 24% minor) should be factors.

In some cases, college graduates have different views on this than those who did not graduate from college. For example, while 57% of those with a four-year college degree say whether someone is the first in their family to attend college should be a major or minor factor in making admissions decisions, 43% of those without a bachelor’s degree say the same.

The value of a college degree

Despite the public’s increasingly negative views about higher education and its role in society, most Americans say a college education is important – if not essential – in helping a young person succeed in the world today. A 2018 Center survey found that 31% of adults say a college education is essential, and an additional 60% say it is important but not essential. However, far higher shares say a good work ethic (89%), the ability to get along with people (85%), and work skills learned on the job (75%) are essential for a young person to succeed.

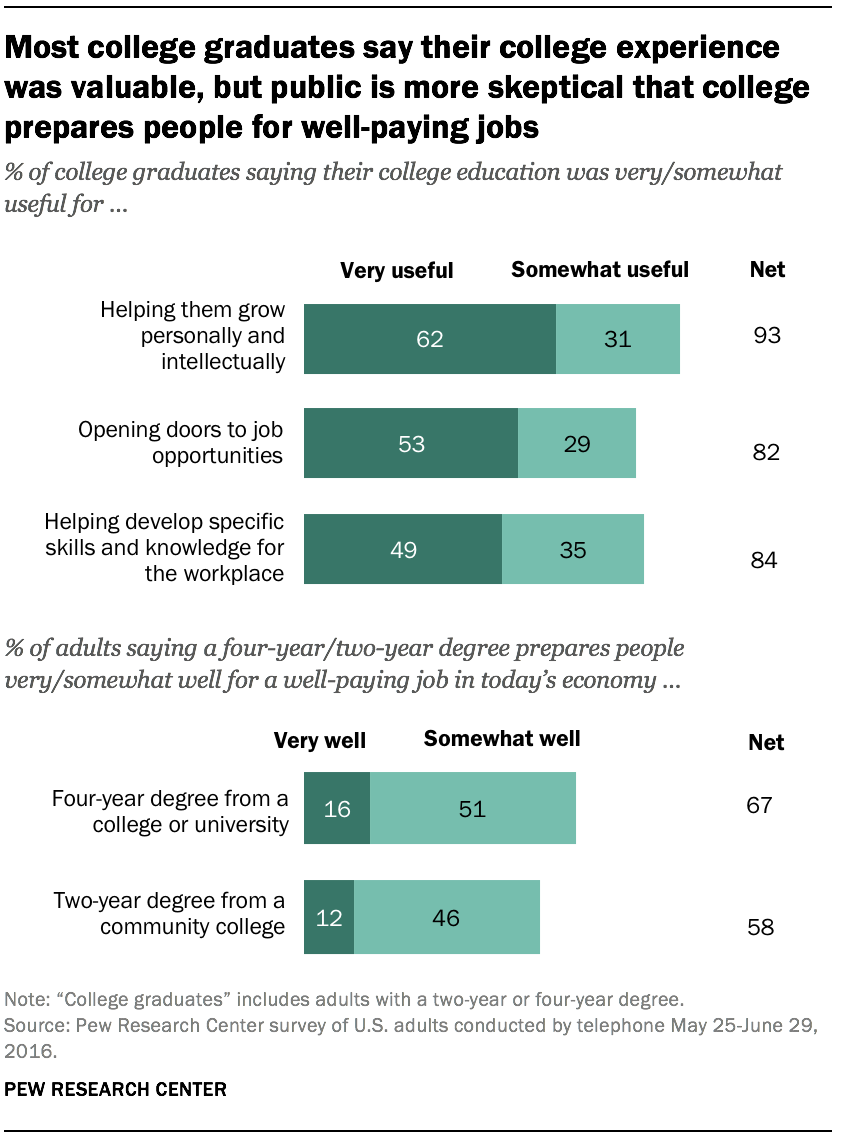

When it comes to their own experiences with higher education, an earlier Center survey found that the vast majority of college graduates (from both two- and four-year institutions) say college was useful for them in terms of helping them grow personally and intellectually (62% say it was very useful in this regard, 31% say it was somewhat useful). Large majorities also say it was useful in opening doors to job opportunities (53% say very useful, 29% say somewhat) and in helping them develop specific skills and knowledge that could be used in the workplace (49% very, 35% somewhat).

Still, the public remains skeptical that today’s colleges are preparing people for the workforce. Only 16% say a four-year degree from a college or university prepares someone very well for a well-paying job in today’s economy, while 51% say it prepares them somewhat well. Community colleges get even less positive marks: 12% say a two-year degree from these colleges prepares someone very well for a job, and 46% say it prepares them somewhat well.

These views generally don’t differ markedly by educational attainment. Among adults with a four-year college degree or higher, 13% say a four-year degree prepares someone very well for a well-paying job; 11% of those with an associate degree say the same, as do 12% of those with some college experience but no degree and 17% of those with no education beyond high school. However, among those who didn’t complete high school, a much higher share – 40% – say a four-year college degree prepares someone very well for a well-paying job.

Republicans and Democrats have similar opinions on this, although Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say a four-year degree prepares people somewhat well for a high-paying job in today’s economy.

There’s a larger party gap in views on the main purpose of college. A majority of Republicans (58%) say it should be to teach specific skills and knowledge that can be used in the workplace, while only 28% say it should be to help an individual grow personally and intellectually. Democrats are more evenly divided on this: 43% say the main purpose of college should be developing skills and knowledge, while roughly the same share (42%) point to personal and intellectual growth.

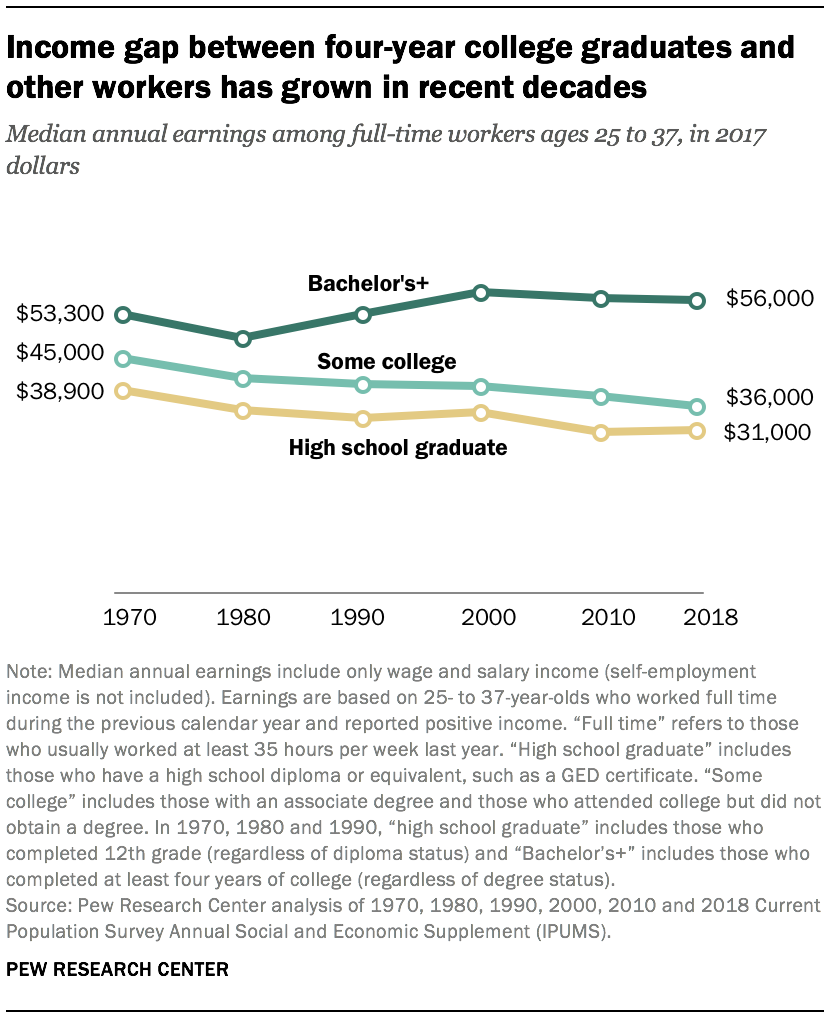

Even amid doubts about the extent to which college prepares people for today’s job market and disagreement about what the role of college should be, the fact remains that a four-year college degree has very real economic benefits. The income gap between college graduates and those without a bachelor’s degree has grown significantly over the past several decades. In 1990, the median annual earnings for a full-time worker ages 25 to 37 with a bachelor’s degree or higher was $53,600. At the time, this compared with $40,200 for a worker with some college experience but no bachelor’s degree and $33,600 for a worker with no college experience. In 2018, the difference was even more pronounced: $56,000 for a worker with a bachelor’s degree or more education, $36,000 for someone with some college education and $31,300 for a high school graduate.

This broad overview of data on views about higher education in the U.S. reveals a complex set off attitudes – a public that still sees the benefit of a college education but has grown wary about the politics and culture on college campuses and the value of a four-year degree that has an ever-increasing price tag.

The partisan gaps underlying these views are reflective of our politics more broadly. From health care to the environment to immigration and foreign policy, Republicans and Democrats increasingly see the issues of the day through different lenses. But views on the nation’s educational institutions have not traditionally been politicized. Higher education faces a host of challenges in the future – controlling costs amid increased fiscal pressures, ensuring that graduates are prepared for the jobs of the future, adapting to changing technology and responding to the country’s changing demographics. Ideological battles waged over the climate and culture on college campuses may make addressing these broader issues more difficult.