How we did this

Pew Research Center conducted this study to understand Americans’ health concerns surrounding the coronavirus outbreak. For this analysis, we surveyed 4,917 U.S. adults in April 2020. Everyone who took part is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

See here to read more about the questions used for this report and the report’s methodology.

As the number of confirmed cases of the new coronavirus continues to climb in the United States, the current epicenter of the global pandemic, majorities of Americans are concerned that they may contract the disease and that they may unknowingly spread it to others.

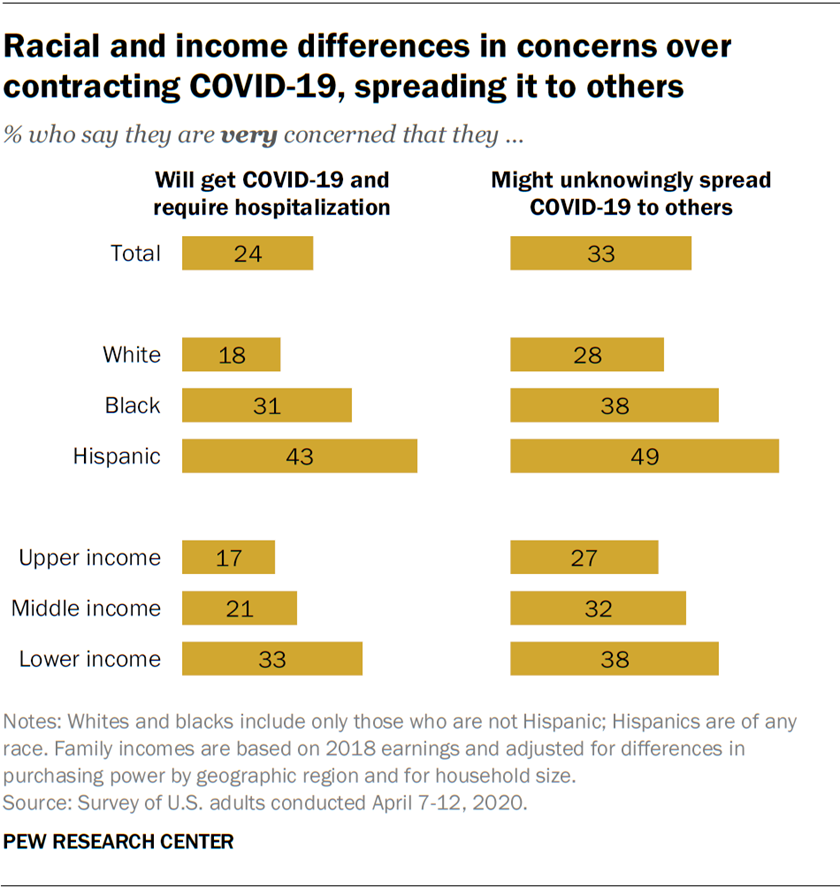

Yet these concerns are much more widespread among black and Hispanic adults than white adults. And there also are differences in concerns across income levels: A third of Americans with lower incomes say they are very concerned they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization. Among upper-income adults, only about half as many (17%) are very concerned.

Among the public overall, a majority (55%) say they are very or somewhat concerned they will get COVID-19 and require hospitalization; nearly a quarter are very concerned. An even larger share (66%) are concerned they may unknowingly spread the disease to others, including 33% who are very concerned about this.

About half of Hispanic adults (49%) are very concerned about unknowingly spreading COVID-19 to others, compared with 38% of black adults and 28% of white adults. And Hispanics (43%) and blacks (31%) are far more likely than whites (18%) to be very concerned over getting COVID-19 and needing to be hospitalized.

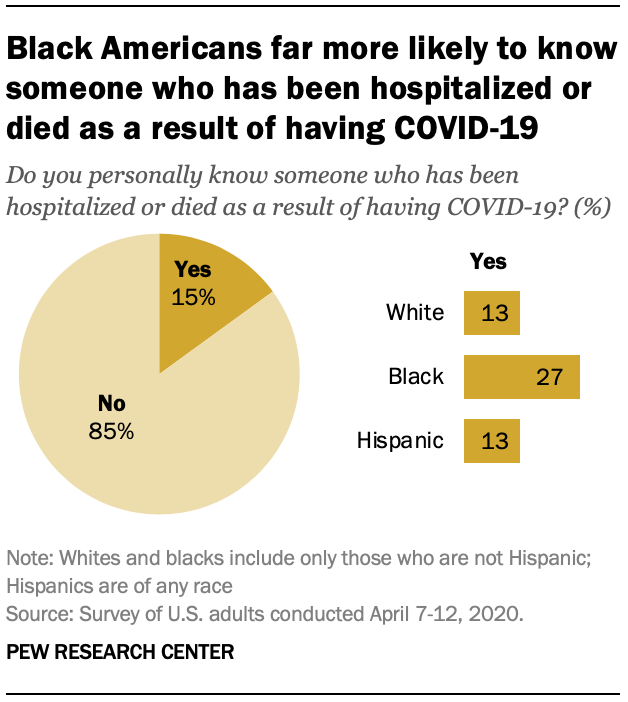

The new national survey by Pew Research Center, conducted April 7 to 12 among 4,917 U.S. adults on the American Trends Panel, finds sharp racial disparities in personal experiences with knowing people who have had serious illnesses arising from COVID-19.

Among the public overall, 15% say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or died as a result of having COVID-19.

However, about a quarter of black adults (27%) say they personally know someone who has been hospitalized or died due to having the coronavirus. By comparison, about one-in-ten white (13%) and Hispanic (13%) adults say they know someone who has been so seriously affected by the virus.

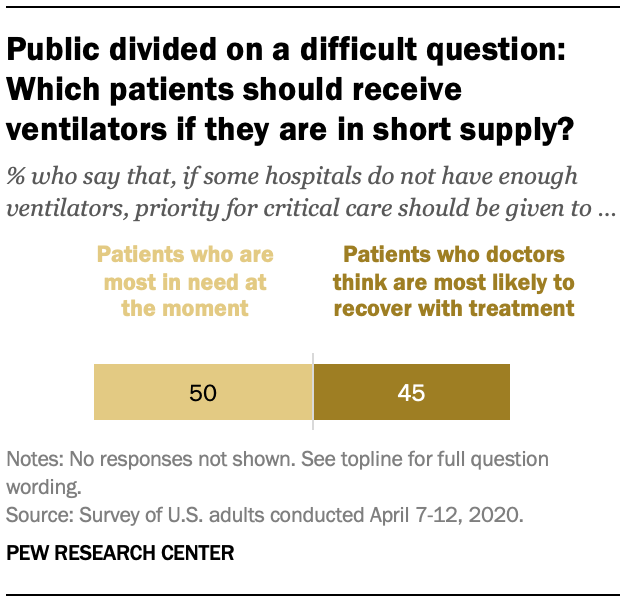

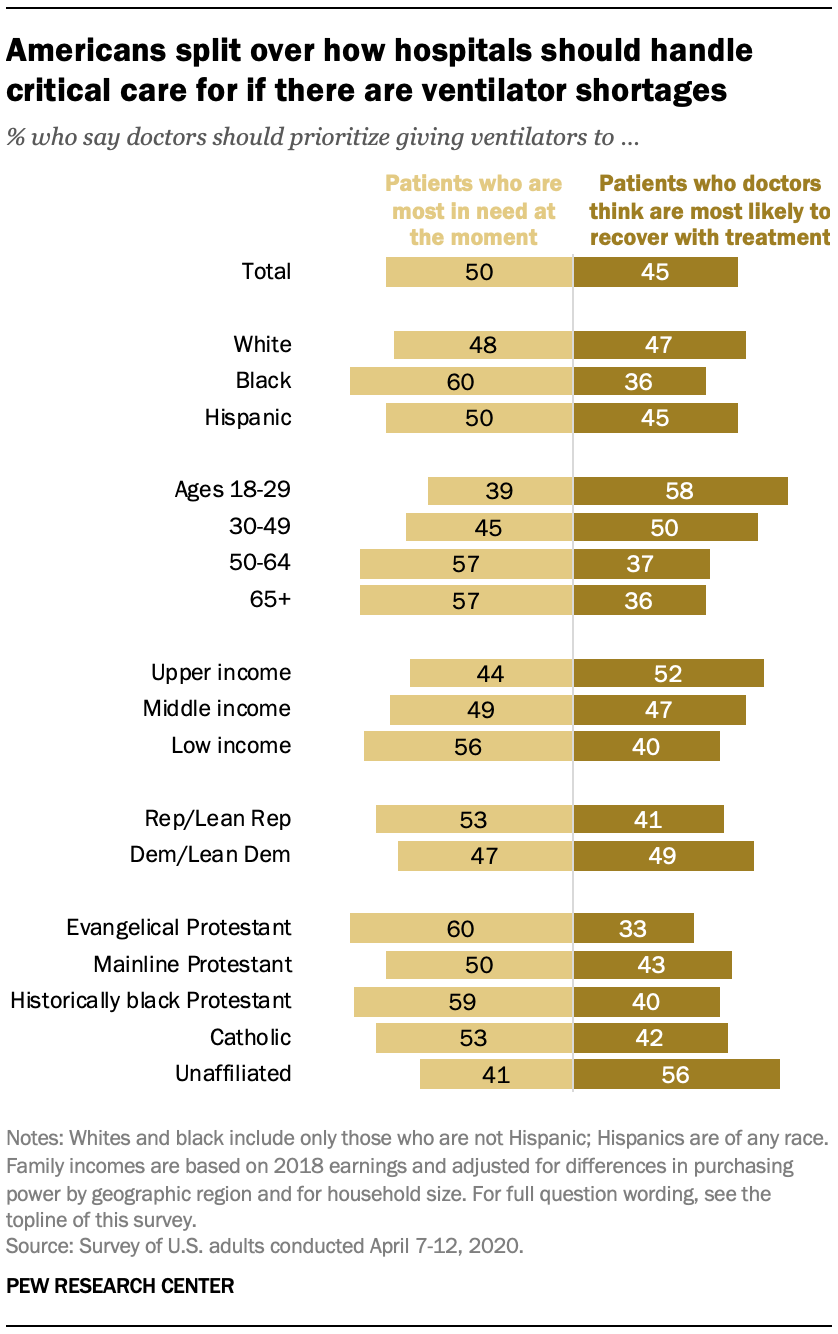

Amid reports that some states and cities may face shortages of ventilators to treat seriously ill COVID-19 patients, some states have developed guidelines for how hospitals and doctors should allocate ventilators if they become scarce.

The survey asks about the priority for critical care if the availability of ventilators became limited in some hospitals.

Among U.S. adults overall, 50% say the priority for critical care in that case should be given “to patients who are most at need in the moment, which may mean fewer people overall survive, but doctors do not deny treatment based on age or health status.”

Nearly as many (45%) say the priority should be giving critical care to “patients who are most likely to recover with treatment, which may mean more people survive, but that some patients don’t receive treatment because they are older or sicker.”

Opinions on this question differ by race and ethnicity, partisanship and education. There also are substantial age differences: Adults under age 30 are the only age group in which a majority (58%) says the priority for critical care should be patients with the best chance of recovery. Those ages 30 to 49 are divided, while a majority of those 50 and older (57%) say the priority should be for patients most in need at the moment.

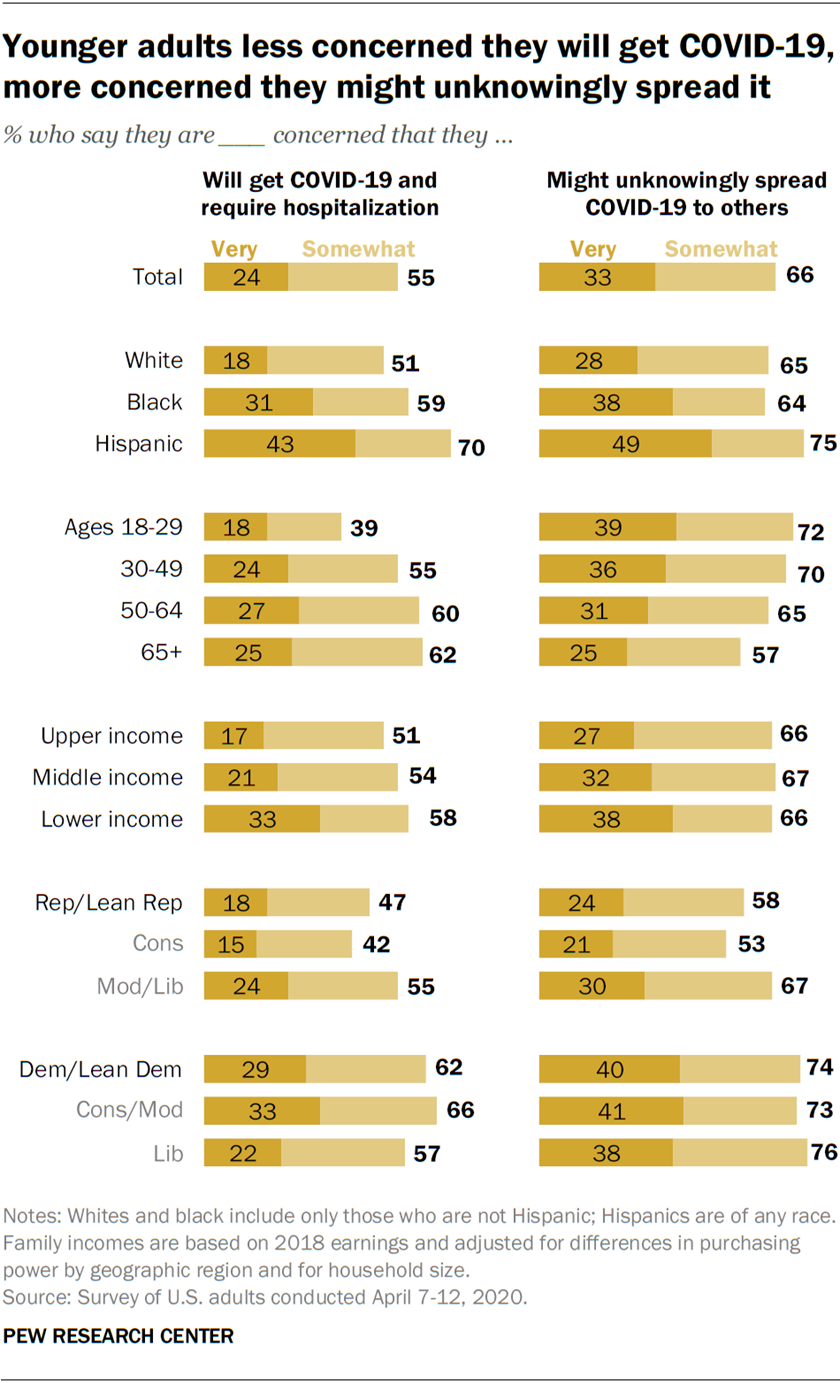

Concerns about getting, spreading COVID-19 differ by race, age, income, party

Just over half of Americans reports being at least somewhat concerned that they could be hospitalized due to the coronavirus (55%) and about two-thirds express concern that they might unknowingly spread it to others (66%). But there are stark racial and ethnic, income, age and partisan differences in the shares saying this.

For example, while about six-in-ten adults ages 50 and older (61%) are at least somewhat concerned that they will be hospitalized due to catching the coronavirus, only about four-in-ten adults younger than 30 (39%) say the same.

In contrast, younger adults are more concerned than older adults that they might spread the coronavirus to others without knowing they have it – 72% of 18- to 29-year-olds say they are at least somewhat concerned this could happen, including 39% who say they are very concerned. Among those 65 and older, 57% say they are at least somewhat concerned about this, including a quarter who are very concerned.

Both black and Hispanic adults are substantially more likely than white adults to express high levels of concern over the possibility they will get the coronavirus or transmit it to others, with Hispanics particularly likely to report having these concerns.

Seven-in-ten Hispanic adults (70%) say they are at least somewhat concerned that they will be hospitalized due to the coronavirus (including 43% who are very concerned about this). Among black Americans, nearly six-in-ten (59%) are at least somewhat concerned about this, including about a third (31%) who are very concerned. By comparison, about half of white adults (51%) express some concern about the possibility of hospitalization as a result of COVID-19, with just 18% reporting being very concerned about this. There are similar racial and ethnic differences in concerns about the possibility of unknowingly being a vector for the spread of the coronavirus.

Republican and Republican-leaning independents are far less likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to say they are at least somewhat concerned they will be hospitalized due to getting COVID-19 (47% vs. 62%) or that they may spread the coronavirus to others (58% vs. 74%).

However, moderate and liberal Republicans express higher levels of concern about these possibilities than do conservative Republicans. For example, 55% of moderate and liberal Republicans say they are concerned they will get COVID-19 and be hospitalized, while 42% of conservative Republicans say the same.

And although conservative and moderate Democrats (66%) are more likely than liberal Democrats (57%) to say they are at least somewhat concerned they will be hospitalized due to the coronavirus, roughly similar shares of each group express concern about spreading the coronavirus to others.

Democrats and those in hard-hit counties more likely to have concerns about contracting or unknowingly spreading COVID-19

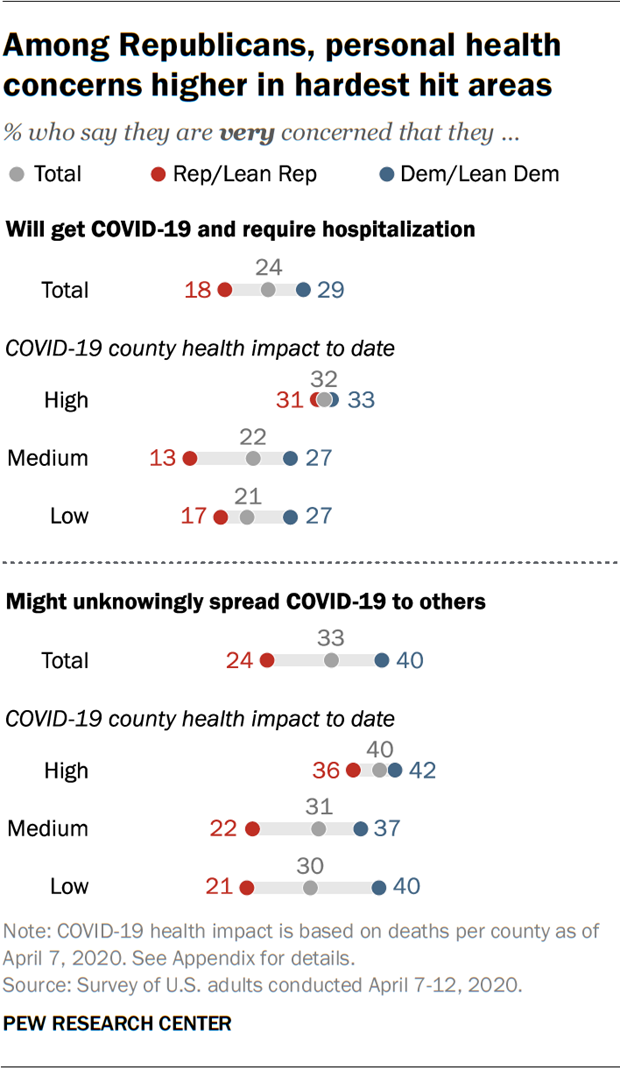

Overall, Americans living in counties hit harder by COVID-19 are more likely to say they are very concerned about getting or spreading the coronavirus.

In particular, Republicans living in counties with higher numbers of COVID-19 deaths are substantially more likely than Republicans living in other parts of the country to say they are very concerned they will get or might spread the coronavirus.

For example, Republicans in counties with more reported deaths from the coronavirus (31%) are about twice as likely to be very concerned that they will get the coronavirus and be hospitalized than those in counties where deaths per county can be classified as more moderate (13%) or low (17%).

Among Democrats, there are only modest geographic differences in levels of concern.

Although Democrats overall remain more likely than Republicans to express concerns about getting or transmitting the coronavirus even accounting for county-level COVID-19 health impact, these differences are more pronounced in areas of the country that have seen fewer deaths than the rest of the country.

If ventilators become scarce, what should the priority be for critical care?

For several weeks there have been concerns about possible ventilator shortages in hospitals with COVID-19 patients, and concerns that medical providers might need to make decisions on how to allocate ventilators if that occurred. Among the public, half (50%) say that, if a shortage occurs, the priority for critical care should be given to patients most in need at the moment, while nearly as many (45%) say the priority should be to patients who doctors think are most likely to recover with treatment.

There are differences in these views across groups, including by age, race, income, party and religious tradition.

A majority (58%) of adults under age 30 say the priority in the case of limits on access to ventilators should be “patients who doctors think are most likely to recover with treatment, which may mean more people survive but that some patients don’t receive treatments because they are older or sicker.” By comparison, nearly six-in-ten adults ages 50 and older (57%) say the priority should be “patients who are most in need at the moment, which may mean fewer people overall survive, but doctors do not deny treatments based on age or health status.”

There are also substantial differences in these views by religious affiliation. Roughly six-in-ten evangelical Protestants (60%) and those affiliated with historically black Protestant denominations (59%) say that the priority should be given to patients based on their need in the moment. Opinion leans in the same direction among Catholics (53% say give priority to those most in need vs. 42% who say give priority to those most likely to recover). Mainline Protestants are divided about evenly on this question, while most religiously unaffiliated respondents say patients who are most likely to recover with treatment should be given priority if ventilators are scarce (56%).