Western Europeans tend to highly value the news media in their countries generally but the level of trust they place in the media varies among countries. Differences also emerge between people with and without populist leanings. In nearly all eight countries included in this survey, those who hold populist views also give the news media lower marks for coverage of major issues, such as immigration, the economy and crime.5

The study also finds that attitudes toward the news media vary along regional lines. In general, Europeans in southern countries (France, Italy and Spain) as well as those in the UK are more skeptical of the news media than northern Europeans.6

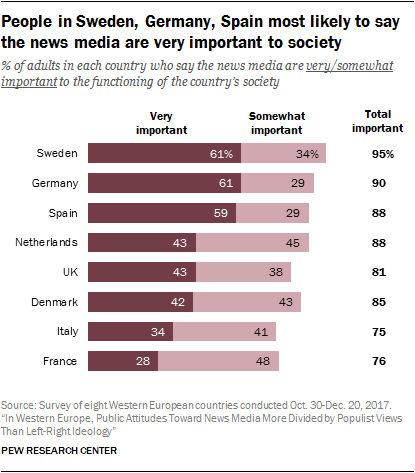

Broad majorities say the news media are important to society, but the level of importance varies by country and populist leanings

Across the eight European countries studied, three-quarters or more of the publics say the news media are at least somewhat important to the functioning of the country’s society. But the share that says that the news media’s role is very important varies significantly.

Sweden, Germany and Spain sit at the top: Strong majorities in each of those three countries (between 59% and 61% of adults) say the news media are very important to the functioning of society. In France, on the other hand, less than a third feel this way, the smallest share among the eight countries surveyed.

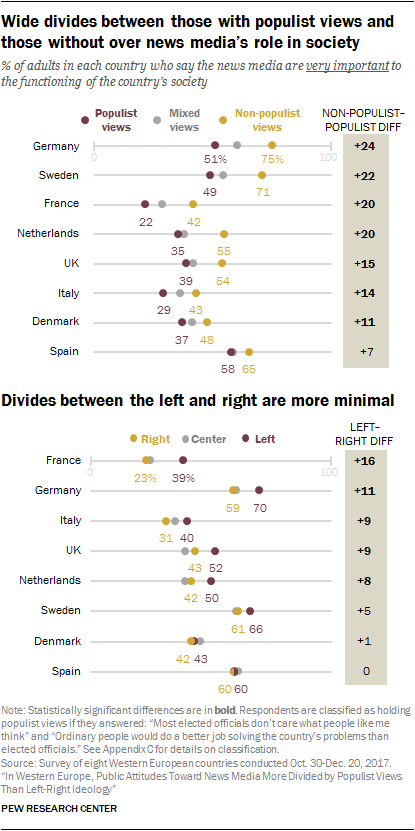

Views on the importance of the news media are divided within each country as well. In most of the countries surveyed, populist leanings – more than left-right political identity – are a key factor, with those holding populist views less likely to value the news media.

Differences between those who hold populist views and those who don’t range from a low of 11 percentage points in Denmark to 24 points in Germany. Spain is the only country where there is no significant difference between these two groups on this question.

When left-right differences do emerge, they are more minimal than those along populist lines. In Germany for instance, 70% of those who place themselves on the left of the ideological scale say the news media are very important, compared with 59% of those on the right, a gap of 11 percentage points. In comparison, the gap between those who embrace populist views and those who don’t is 24 percentage points in Germany. In three countries – Sweden, Denmark and Spain – no significant difference exists in divides between those on the left and right.

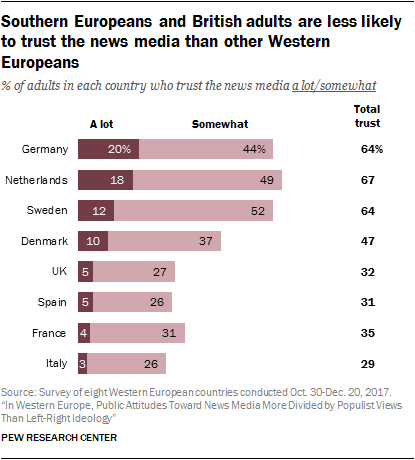

Trust in news media differs by region and populist leanings

Few Western Europeans surveyed deeply trust the news media. No more than one-in-five in any of the eight countries say they trust the news media a lot.

Southern Europeans, in particular, are skeptical of the news media. Roughly a third or less in Spain, France and Italy say they trust the news media, with 5% or less saying they have a lot of trust. This pattern is similar in the UK, with 5% of British adults trusting the news media a lot. In contrast, trust is substantially higher in the other northern European countries surveyed.

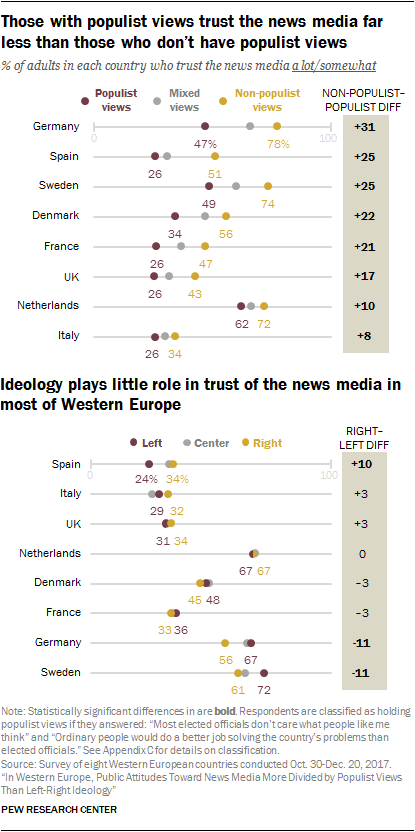

Trust in the news media also varies between those with and without populist leanings. People who hold populist views are less trusting of the news media than those who do not hold such beliefs. The divides range from 31 percentage points in Germany to 8 points in Italy.

People with populist views in Spain, France, the UK and Italy are particularly distrusting of the news media. Only about a quarter (26%) of populists in each of these countries say they trust the news media at least somewhat.

Whether someone identifies as politically on the left or right has less influence than populist views on whether they trust the news media. Western Europeans who place themselves on the ideological left and those who place themselves on the ideological right generally agree on how much they trust the news media. Only in three of the countries studied are publics divided in their trust of the news media along the left-right ideological spectrum. In Spain, those on the right are more likely to trust the news media than those on the left. In Germany and Sweden the opposite is true – those on the left are more likely to trust the news media than those on the right.

News media receive low ratings for political neutrality and immigration coverage, with large divides among those with populist views

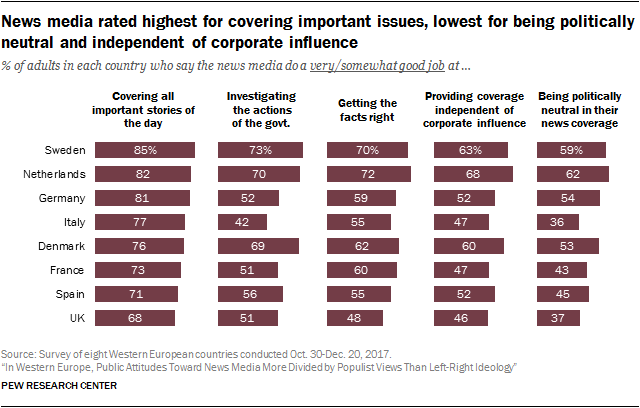

Overall, Western Europeans give the news media fairly high ratings on several core functions, though attitudes are more negative in the southern European countries and the UK. Among five measures asked, Western Europeans give the news media lowest marks for providing news independent of corporate influence and for being politically neutral in their coverage. For instance, less than half of the publics in Spain (45%), France (43%), the UK (37%) and Italy (36%) say that their news media are doing a good job being politically neutral in their coverage. On the other hand, broad majorities in all eight countries say their news media do a good job covering the important stories of the day. (For more on how Western Europeans compare with the rest of the world, see the Pew Research Center report on 38 countries and their attitudes toward the news media.)

Overall, embracing populist views is also a strong divider on these questions about news media attitudes. For example, on whether their news media are politically neutral in how they present the news, differences between the two groups – those with populist views and those without – appear in six of the eight countries surveyed. And the gaps range from a 30-percentage-point difference in Germany to a 12-point difference in the Netherlands. (See Appendix D for detailed tables on more breakdowns of attitudes toward the media.)

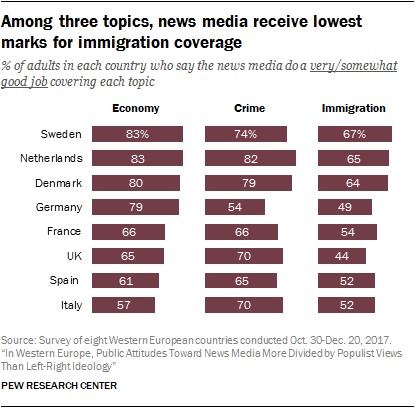

When it comes to coverage of three specific topics in their country – the economy, crime, and immigration –people overall give the news media their highest marks for coverage of the economy and lowest marks for coverage of immigration. Roughly six-in-ten or more in all eight countries say the news media do a somewhat or very good job covering the economy. Similarly, in all but one country, broad majorities say the same about coverage of crime.

But roughly half or fewer in four of the eight countries say the news media cover immigration well, including 44% in the UK. Attitudes are more positive in Sweden, the Netherlands and Denmark, where about two-thirds say their news media do a good job covering the topic of immigration.

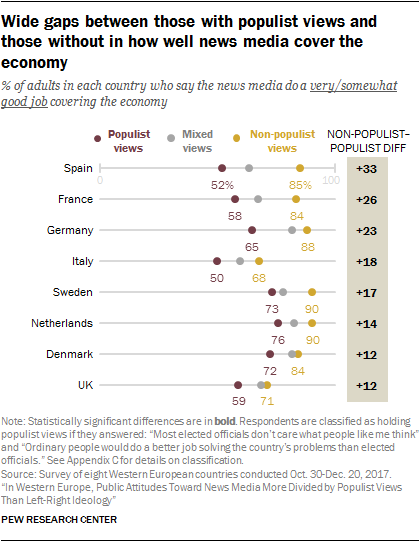

As with the importance of and trust in the news media, there is a wide gap between those who hold populist views and those who don’t when it comes to views of how well the news media cover these topics.

In general, those who hold populist views tend to be less satisfied with the news media’s coverage of all three topics. In the case of the economy, this gap ranges from a 33-percentage-point difference in Spain to a 12-point difference in the UK and Denmark. For example, in Spain, 52% of those who hold populist views say that the news media do a good job covering the economy, compared with 85% of those who don’t hold populist views.

This divide between those with populist views and those without also exists for assessments of the news media’s coverage of immigration and crime. In the case of immigration, the gap between the two groups ranges from a 29-point difference in Germany to an 11-point difference in Italy and Denmark, while for crime the difference ranges from 31 points in Germany to 9 points in the Netherlands (there was no statistical difference between the two groups in Italy on crime). See detailed tables for figures on the other topics.

Assessments of the news media’s coverage of immigration and crime also show left-right divisions in most countries. Still, populism is the larger divide.