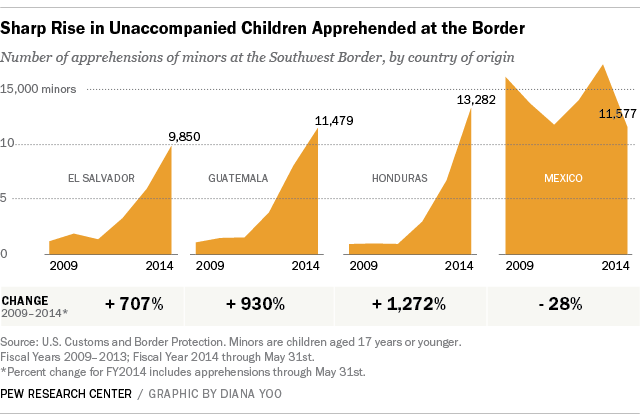

With the surge in unaccompanied children apprehended at the Southwest border, much has been written about the unusually high numbers of kids arriving from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. The number of apprehensions of Mexican child migrants rivals those of the other three countries, but many of those caught are ones who tried to cross multiple times — meaning that the total number of child migrants from Mexico is lower compared with the Central American nations.

Out of the more than 11,000 apprehensions of unaccompanied Mexican minors during this fiscal year (October 1 through May 31), only 2,700 children (24% of all the apprehensions) reported being apprehended for the first time in their lives, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of Mexican government data obtained from the Mexican Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The other three quarters of the apprehensions were of children who reported that they had been apprehended multiple times before — 15% were of children who had been apprehended at least six times.

As a result of these multiple apprehensions, the total number of Mexican children caught at the border is lower than apprehension statistics show. However, the lack of fingerprinting by Mexican authorities makes it difficult to estimate an actual number of children crossing the border. (Note: U.S. and Mexican government totals of Mexican child migrants vary slightly.)

The numbers can be explained, at least in part, by policy. Aside from close geographic location to the U.S. border, it’s easier for Mexicans than Central Americans to attempt multiple crossings into the U.S. because children from Mexico and Canada don’t receive the same protections as those from other countries under a 2008 human trafficking law. The law requires Central American children to be processed by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement and placed in housing, preferably with a family member, while their immigration cases are processed in U.S. immigration court.

By contrast, Mexican children can be returned to Mexico within hours of their apprehension. Under current policy, U.S. authorities try to determine whether Mexican children have been victims of human trafficking or face some other credible fear of persecution. Suspected victims are treated similarly to Central American children and placed in housing. But the remaining children are returned to the border within 72 hours and handed over to Mexican consulate officials.

As a result, 95% of unaccompanied children from Mexico were returned almost immediately after their apprehension during the last fiscal year, according to a report prepared by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

Another difference between apprehended unaccompanied children from Mexico and Central America is in demographic characteristics such as age and gender. For example, girls make up about 34% of unaccompanied children from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala, compared with just 8% from Mexico. Children from Mexico also tend to be older. About 97% of unaccompanied minors apprehended from Mexico this fiscal year were teenagers, compared with 80% from Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

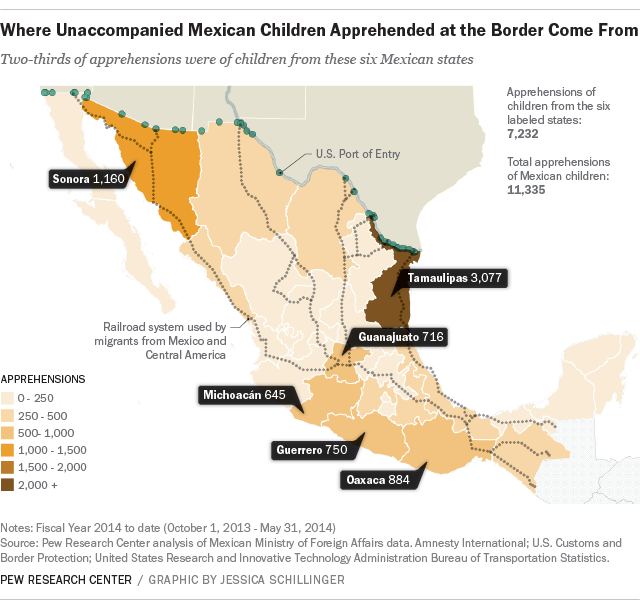

The Mexican data also give fresh insights into which states in Mexico the children are from. The top six Mexican states accounted for 64% of the 11,335 apprehensions of Mexican unaccompanied children this fiscal year.

About one-in-four (3,077) children apprehended this fiscal year came from the border state of Tamaulipas. The Mexican state’s shared border with Texas overlaps with the Border Patrol Sector where the vast majority of all apprehensions of unaccompanied minors have taken place this year. Tamaulipas is also the end of the line for one section of an infamous freight train network, nicknamed “La Bestia,” that thousands of migrants have used to reach the United States.

Poverty and high murder rates have played a role in the surge of child migrants from Central America, according to a U.S. Department of Homeland Security document. But it’s not clear to what extent those factors are driving Mexican children to the United States. Compared with other Mexican states, Tamaulipas does not have a high poverty rate, but violence has spiked in recent years due to Mexican drug cartel turf wars. From 2009 to 2012, the state’s murder rate nearly quintupled to 46 homicides per 100,000 people — about double the rate of Mexico overall. The rate is also higher than in El Salvador (41) and Guatemala (40).

Another 10% of apprehensions this fiscal year are from Sonora, a state that borders Arizona. Like most Mexican border states, Sonora also has a low poverty rate, but it is a hub for migrants traveling across Mexico by train to reach the United States. Unlike Tamaulipas, Sonora has a relatively low homicide rate (19 per 100,000).