Large racial and gender wage gaps in the U.S. remain, even as they have narrowed in some cases over the years. Among full- and part-time workers in the U.S., blacks in 2015 earned just 75% as much as whites in median hourly earnings and women earned 83% as much as men.

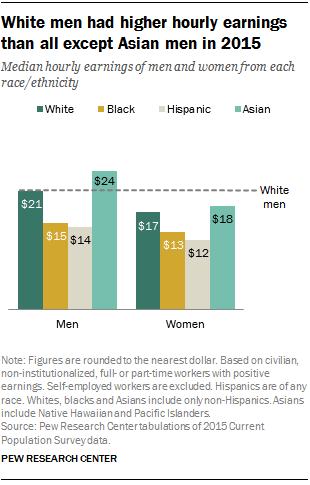

Looking at gender, race and ethnicity combined, all groups, with the exception of Asian men, lag behind white men in terms of median hourly earnings, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of Bureau of Labor Statistics data. White men are often used in comparisons such as this because they are the largest demographic group in the workforce – 33% in 2015.

In 2015, average hourly wages for black and Hispanic men were $15 and $14, respectively, compared with $21 for white men. Only the hourly earnings of Asian men ($24) outpaced those of white men.

Among women across all races and ethnicities, hourly earnings lag behind those of white men and men in their own racial or ethnic group. But the hourly earnings of Asian and white women ($18 and $17, respectively) are higher than those of black and Hispanic women ($13 and $12, respectively) – and also higher than those of black and Hispanic men.

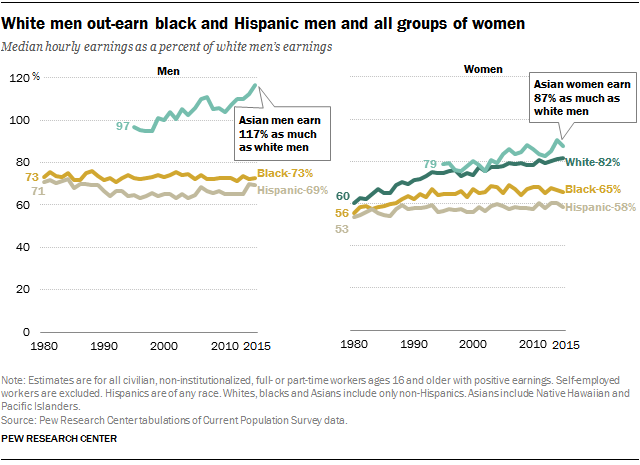

While the hourly earnings of white men continue to outpace those of women, all groups of women have made progress in narrowing this wage gap since 1980, reflecting at least in part a significant increase in the education levels and workforce experience of women over time.

White and Asian women have narrowed the wage gap with white men to a much greater degree than black and Hispanic women. For example, white women narrowed the wage gap in median hourly earnings by 22 cents from 1980 (when they earned, on average, 60 cents for every dollar earned by a white man) to 2015 (when they earned 82 cents). By comparison, black women only narrowed that gap by 9 cents, from earning 56 cents for every dollar earned by a white man in 1980 to 65 cents today. Asian women followed roughly the trajectory of white women (but earned a slightly higher 87 cents per dollar earned by a white man in 2015), whereas Hispanic women fared even worse than black women, narrowing the gap by just 5 cents (earning 58 cents on the dollar in 2015).

Black and Hispanic men, for their part, have made no progress in narrowing the wage gap with white men since 1980, in part because there have been no improvements in the hourly earnings of white, black or Hispanic men over this 35-year period. As a result, black men earned the same 73% share of white men’s hourly earnings in 1980 as they did in 2015, and Hispanic men earned 69% of white men’s earnings in 2015 compared with 71% in 1980.

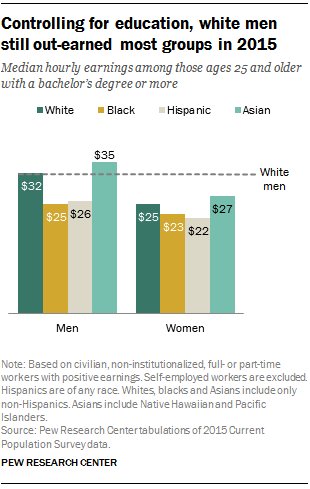

To be sure, some of these wage gaps can be attributed to the fact that lower shares of blacks and Hispanics are college educated. U.S. workers with a four-year college degree earn significantly more than those who have not completed college. Among adults ages 25 and older, 23% of blacks and 15% of Hispanics have a bachelor’s degree or more education, compared with 36% of whites and 53% of Asians.

However, looking just at those with a bachelor’s degree or more education, wage gaps by gender, race and ethnicity persist. College-educated black and Hispanic men earn roughly 80% the hourly wages of white college educated men ($25 and $26 vs. $32, respectively). White and Asian college-educated women also earn roughly 80% the hourly wages of white college-educated men ($25 and $27, respectively). However, black and Hispanic women with a college degree earn only about 70% the hourly wages of similarly educated white men ($23 and $22, respectively). As with workers overall, college-educated Asian men out-earn college-educated white men by about $3 per hour of work.

What contributes to these persistent wage gaps? Research shows that a majority of each of these gaps can be explained by differences in education, labor force experience, occupation or industry and other measurable factors.

For example, NBER researchers Francine Blau and Lawerence Kahn found that education and workforce experience accounted for 8% of the total gender wage gap in 2010, while industry and occupation explained 51% of the difference. When it comes to race, sociologists Eric Grodsky and Devah Pager found that education and workforce experience accounted for 52% of the wage gap between black and white men working in the public sector in 1990, and that adding occupational differences explained approximately 20% of the wage gap. And NBER researcher Roland Fryer found that for one group of adults in their 40s, controlling for standardized-test scores reduced the wage gap between black men and white men in 2006 by roughly 70%.

The remaining gaps not explained by these concrete factors are often attributed, at least in part, to discrimination. Blau and Kahn point out, however, that there are both portions of this “unmeasured” difference that could be due to factors other than discrimination (e.g., gender differences in behaviors like risk aversion or negotiation) as well as portions of the “measured” difference that may in fact be due to discrimination (e.g., a woman or minority not entering a high-paying STEM field because of experiences that may be rooted in prejudice, such as greater encouragement for men than women to pursue these studies).

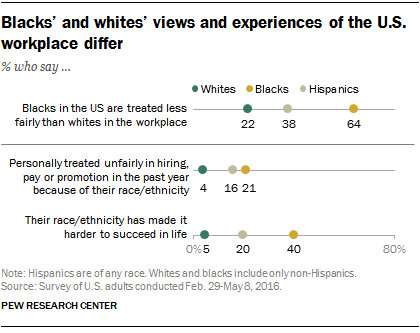

When it comes to racial discrimination in the workplace, most Americans (60%) say blacks and whites are treated about equally, but opinions on this vary considerably across racial and ethnic groups. A new Pew Research Center report finds that roughly two-thirds (64%) of blacks say black people in the U.S. are generally treated less fairly than whites in the workplace; just 22% of whites and 38% of Hispanics agree.

About two-in-ten black adults (21%) and 16% of Hispanics say that in the past year they have been treated unfairly in hiring, pay or promotion because of their race or ethnicity; just 4% of white adults say the same. And while 40% of blacks say their race or ethnicity has made it harder for them to succeed in life, just 5% of whites – and 20% of Hispanics – say this. Some 31% of whites say their race or ethnicity has eased the way toward their success. At least six-in-ten whites (62%) and Hispanics (65%), and about half of blacks (51%), say their race or ethnicity hasn’t made much of a difference.

For their part, about a quarter of women (27%) say their gender has made it harder for them to succeed in life, compared with just 7% of men. About six-in-ten men and women say their gender hasn’t made much difference, but men are much more likely than women to say their gender has made it easier to succeed (30% vs. 8%). In addition, a 2013 Pew Research Center survey found that about one-in-five women (18%) say they have faced gender discrimination at work, including 12% who say they have earned less than a man doing the same job because of their gender. By comparison, one-in-ten men say they have faced gender-based workplace discrimination, including 3% who say their gender has been a factor in earning lower wages.