Countries around the world have different systems for financially supporting religious institutions. In the U.S., direct taxpayer funding is prohibited by the Constitution, but churches receive tax exemptions. In some countries in Western Europe, by contrast, churches and other religious institutions are funded through taxes levied by the government.

Even though most Western Europeans are not very religious, and those who live in countries with a church tax can opt out of paying it, support for the tradition remains strong in the region, according to a new Pew Research Center report, based on a 2017 survey of 15 countries. The study examines public attitudes toward church taxes by comparing the views of Western Europeans who say they pay such taxes with those who have opted out.

Here are seven key takeaways from the report:

Six of 15 surveyed Western European countries have a mandatory church tax for members of religious groups. They are Austria, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Sweden and Switzerland.

While the rules for administering the tax or fee vary from country to country, each nation generally assesses a portion of the income (or taxes paid) of taxpayers who are members of the country’s larger churches. While most registered Christians – and, in some countries, members of other religious groups – must pay the tax, people have the option of avoiding the tax by deregistering from their church. The money collected usually pays for church expenses, including clergy salaries, maintaining buildings and funding church charities.

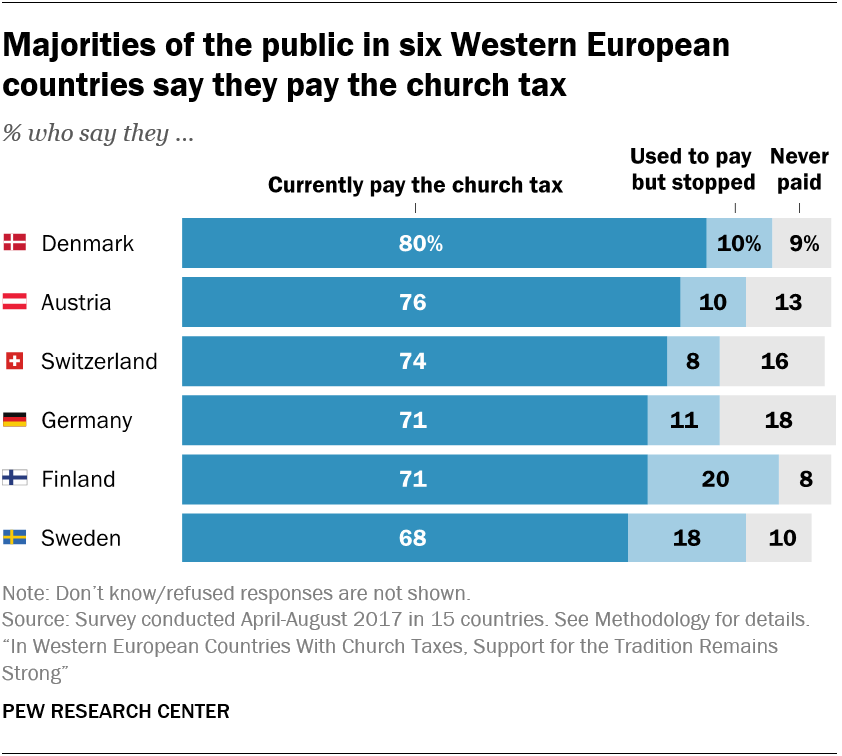

Sizable majorities of adults in all six countries with a mandatory tax say they pay it. Eight-in-ten Danes and roughly three-quarters of Austrians (76%) and Swiss (74%) say they pay the tax. In each country, a small share of adults – ranging from 8% in Switzerland to 20% in Finland – say they used to pay the tax but no longer do so.

In Germany and Austria, the share of people who say they pay the church tax drastically exceeds the share who actually do pay the tax, according to official statistics. In Germany, for example, roughly seven-in-ten people surveyed say they pay the church tax, but government data indicates the actual figure is only about a quarter of the adult population. There are a number of possible explanations for these discrepancies, but, in any case, the survey captured perceptions about participation in the church tax system.

Few people who currently pay the church tax say they are likely to opt out in the future. In Finland and Denmark, only around one-in-ten of those who say they pay the church tax say they are likely to take official steps to avoid paying it in the future. The share of potential opt-outs is higher in Germany and Switzerland (21% and 26%, respectively), but still is a minority of total church tax payers.

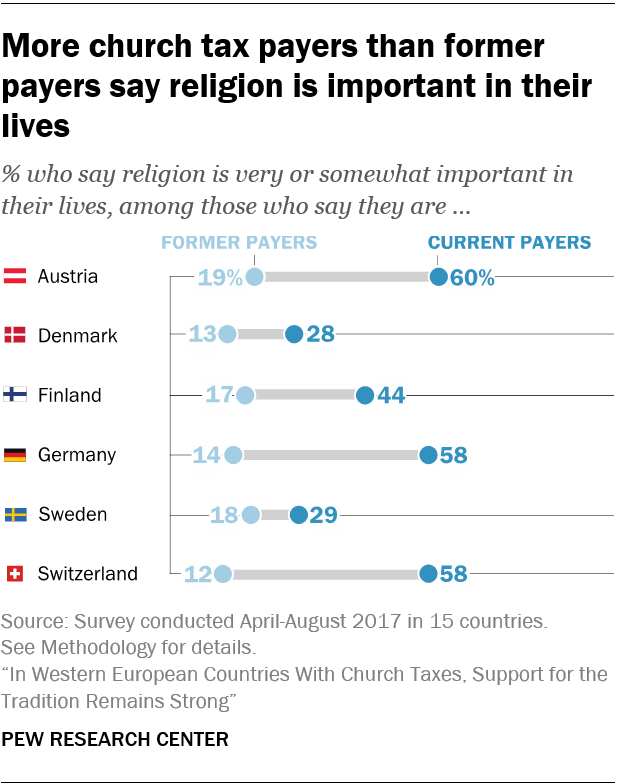

Those who say they pay the church tax are much more likely than those who don’t to identify as Christian and to see religion as important in their lives. The vast majority of church tax payers identify as Christian (in several countries, only those registered with Christian churches are taxed). Those who pay the tax are more likely than former payers to say they attend church regularly and to say religion is important in their lives. Still, the survey finds that taxpayers overall are not highly religious. Most do not attend church regularly, and in Denmark, Finland and Sweden, most do not say religion is important in their life.

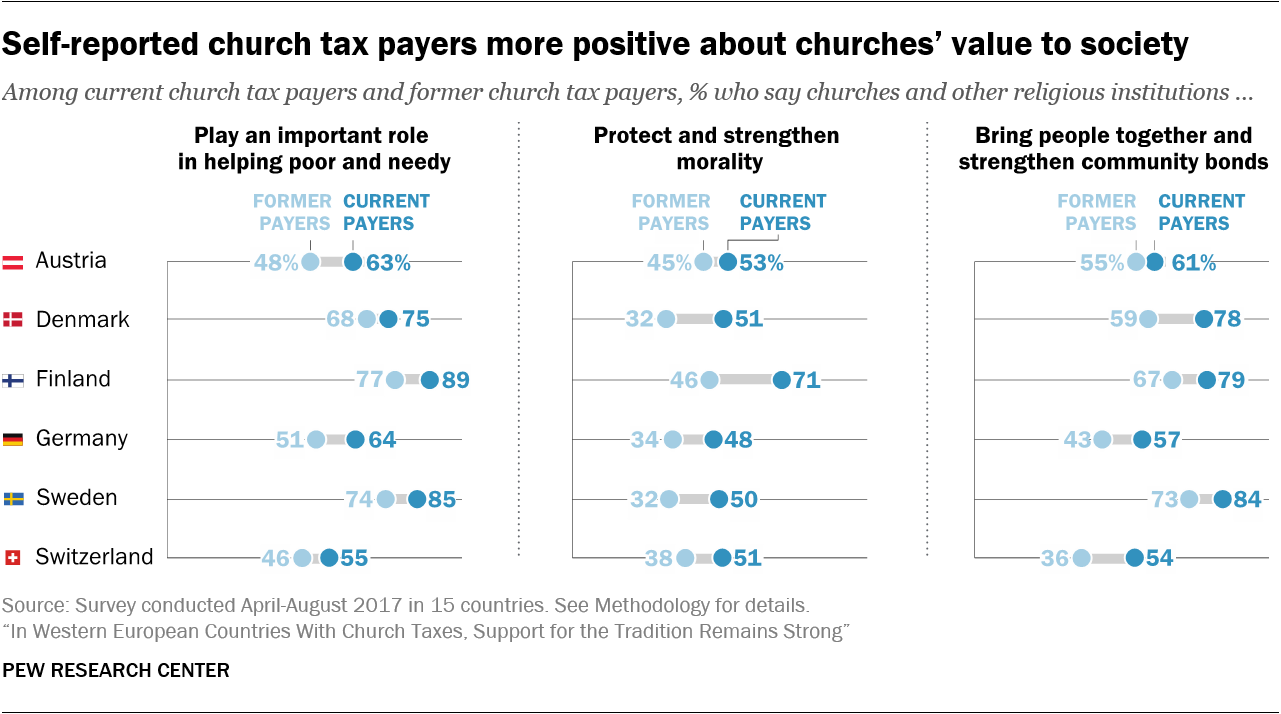

People who pay the church tax have a more positive view of the role of churches in society than those who no longer pay the tax. Current church tax payers are more likely than former payers to say religious institutions strengthen morality, bring people together and play an important role in helping the poor. In Finland, for instance, 71% of people who pay the tax say churches protect and strengthen morality, compared with 46% who say this among those who used to pay the tax but no longer do so.

In countries with a mandatory church tax, younger adults are generally less likely than older adults to say they pay it. In Denmark, for instance, 68% of adults ages 18 to 34 say they pay the tax, compared with 80% of those ages 35 to 54 and 88% of those ages 55 and older. One possible reason for this pattern is that younger adults are more likely than their elders to be religiously unaffiliated. In addition, some younger adults may not be paying because they are students and not yet paying income taxes.