For black Americans, faith and racial justice have long intersected. Throughout history, houses of worship served as central gathering places where black communities discussed political issues and civic action. This often took the form of protest strategy meetings and rallies. But political activism also infused the sermons, hymns and other religious content of many black congregations.

Given that tradition, black Americans and white Americans have differing views on the role that political topics such as race relations and criminal justice reform should play in religious sermons, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted earlier this year, before the killing of George Floyd and the ensuing protests.

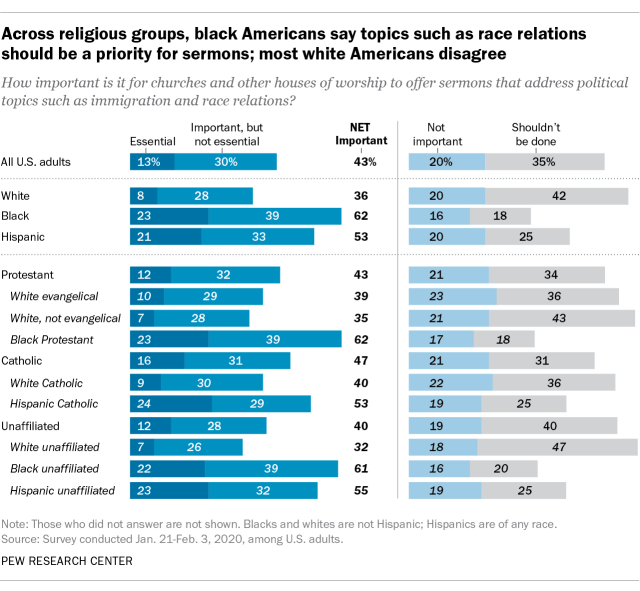

Six-in-ten black adults (62%) say it is important for houses of worship to address “political topics such as immigration and race relations” – including 23% who say covering these topics is “essential.” By contrast, 36% of white Americans say it is important for sermons to deal with these topics, and only 8% say it is essential. Four-in-ten white Americans (42%) say these themes should not be discussed in sermons. Hispanics are more divided on this issue than black or white Americans are; about half (53%) say it is important for sermons to cover political issues.

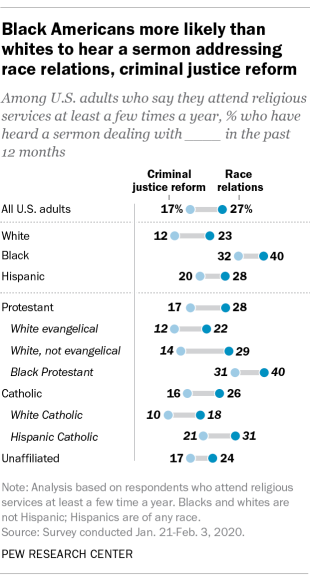

In addition, black Americans are more likely than white or Hispanic Americans to say they have heard political topics such as race relations and criminal justice reform addressed in sermons.

Among those who attend religious services at least a few times a year, four-in-ten black adults say they heard sermons on race relations or racial inequality in their house of worship in the year prior to taking the survey (which was conducted in January and February of 2020) compared with only about a quarter of white (23%) and Hispanic (28%) attenders.

There is a similar pattern on the topic of criminal justice reform. Black Americans are nearly three times as likely as white adults to say they heard a sermon dealing with criminal justice reform (32% vs. 12%) in 2019, with Hispanics falling between the two (20%).

Within racial groups, there are only small differences across religious traditions on these questions. Roughly equal shares of white evangelical Protestants (39%), white Protestants who are not born-again or evangelical (35%) and white Catholics (40%) say it is important for sermons to talk about political topics such as immigration and race relations. Among black Protestants, 62% say it is important f0r sermons to cover these topics, an opinion shared by seven-in-ten (71%) black Americans of other faiths. And although most religiously unaffiliated Americans (those who describe themselves as atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular) do not regularly attend church services, the views of unaffiliated white adults (32%) roughly align with those of affiliated white adults on this question, and the views of unaffiliated black adults (61%) are similar to those of affiliated black adults.

There were too few black respondents who attend religious services at least a few times a year to compare their experiences with sermons across religious traditions, such as black Catholics vs. black Protestants. However, among white respondents who do attend this often, the survey finds little difference in the percentages of evangelicals (12%), Protestants who are not evangelical (14%) and Catholics (10%) who say they heard a sermon about criminal justice reform in 2019. Those figures are far lower than the share of churchgoing black Protestants (32%) who report that they heard a sermon on the same topic. And although white Protestants who are not evangelical (29%) are somewhat more likely than white evangelicals (22%) or white Catholics (18%) to say they have heard a sermon about race relations, they are still less likely than black Protestants (40%) to say this.

Note: Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and its methodology.