The United States and other countries have been struggling for most of this year with the twin challenges posed by the coronavirus outbreak and the havoc it has wreaked on their economies. One key factor in how people assess how their governments are doing in dealing with these challenges is partisanship, measured by the difference in views between those who support a country’s governing party or parties and those who don’t.

Across 13 advanced economies surveyed by Pew Research Center this summer, the association with support (or lack of it) for the governing parties is particularly pronounced in the U.S. when it comes to attitudes about the handling of COVID-19 and the state of the economy.

The American public agrees on one measure, though: Three-quarters say the country is more divided than before the coronavirus outbreak, regardless of whether or not they support the current administration. Relative to those in the 12 other nations surveyed, Americans are united in seeing divisions in their country.

This analysis focuses on how people across 13 advanced economies who do and do not support governing parties or coalitions differ in their views of their country’s experience with the coronavirus outbreak and economic conditions in their country.

This study was conducted in countries where nationally representative telephone surveys are feasible. Due to the coronavirus outbreak, face-to-face interviewing is not currently possible in many parts of the world.

For this report, we use data from nationally representative surveys of 13,085 adults from June 10 to Aug. 3, 2020, in 13 advanced economies. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in the U.S., Canada, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, the UK, Australia and Japan. The questions used for this analysis, along with their responses, can be found here and here. Here is how we developed the governing party variable, and the survey methodology.

For this analysis, we grouped people into two categories: those who support the governing political party (or parties) and those who do not. These categories are based on the party or parties in power at the time the survey was fielded. When different parties occupy the executive and legislative branches of government, the party holding the executive branch was considered the governing party.

In most countries, we determined who did and did not support governing parties based on respondents’ answers to questions asking them which political party in their country, if any, they identified with. Those who said they did not feel close to any party or did not answer the question were considered nonsupporters of the governing party or parties. In countries that are led by a coalition of multiple parties united to form a government, people who said they supported any of the parties in the coalition were considered supporters of the governing party.

In the U.S., we assessed this a bit differently, with both those who identified as Republicans and those who said they leaned toward the Republican Party being considered supporting the governing party, while all others were considered nonsupporters.

Find more information here on how we determine who supports governing parties.

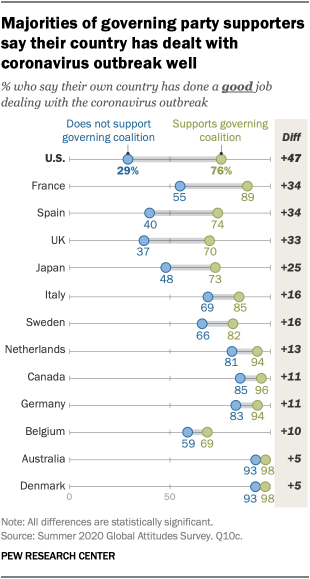

People’s assessments of how well their country had handled the coronavirus outbreak as of this survey – conducted in June through August – were closely tied to partisanship. Governing party supporters were significantly more likely to say their country had done a good job than those who do not support the governing coalition in all 13 countries surveyed. The gap was greatest in the U.S., where about three-quarters of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents said the U.S. had done a good job of handling the coronavirus outbreak, compared with only about three-in-ten among everybody else.

Double-digit gaps of this nature also appear in France, Spain, the UK, Japan, Italy, Sweden, the Netherlands, Canada, Germany and Belgium. This is in spite of the different approaches to dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, from strict national lockdowns in Italy and Spain to the relatively lax approach in Sweden.

In Australia and Denmark, over nine-in-ten respondents overall said that their country had done well dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. Still, supporters of the governing parties in both countries had slightly more positive reviews than those who do not support the governing coalition.

In the U.S., the UK, Spain, Sweden and Australia, those who do not support the coalition in charge also saw a missed opportunity to reduce coronavirus cases. In each of these countries, they were more likely than governing party supporters to say that if their country had cooperated more with other countries, the number of coronavirus cases in their country would have been lower. Again, this gap was largest in the U.S., with 77% of people who do not support the Republican Party holding this view compared with 27% of those who do.

The U.S. is the only country where those who do not support the governing party were more likely to say that their life had changed as a result of the coronavirus outbreak. In every other country, there are no statistically significant differences between governing party supporters and nonsupporters.

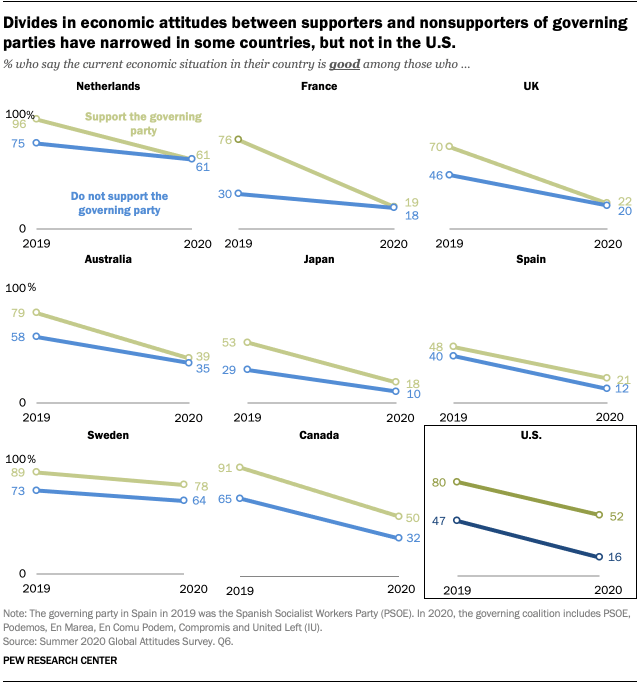

As overall economic attitudes across the world turned sharply negative in 2020, some nations saw political divides in assessments of economic conditions. In six countries – the U.S., Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Spain and Japan – supporters of governing parties were more likely than nonsupporters to rate their country’s current economic situation as good. This rift was largest in the U.S., where Republicans and those who lean Republican were more than three times as likely as those who do not support the party to think the U.S. economy is doing well.

In the U.S., Sweden and Spain, these differences resemble the divides seen in 2019. In the U.S. last year, a sizable majority of Republicans and those who lean toward the party said the economy was faring well, compared with only about half of those who do not identify as Republican or lean toward the party. This year, both camps had gloomier assessments of economic conditions, but a notable difference remains. These divides between partisans have endured in Spain and Sweden too, but these rifts are much smaller than those seen in the U.S.

However, the U.S., Sweden and Spain are outliers in this regard. In most of the countries polled in 2020, attitudes toward the economy do not show partisan divides persisting. In 10 of the 11 countries polled last year for which we have 2020 data to compare, there were significant differences between supporters and nonsupporters of governing parties in assessments of 2019 economic conditions. This year, those divides were only present in six nations. And, in two of those nations, Japan and Canada, while differences in opinion persisted, attitudes converged more than in the past. In these countries, the divide between supporters and nonsupporters narrowed by 16 percentage points in Japan and 8 points in Canada.

In other countries, the gap between supporters and nonsupporters disappeared. For example, last year, supporters of Emmanuel Macron’s En Marche party were 46 points more likely than nonsupporters to rate economic conditions in France positively. This year, both supporters and nonsupporters were about equally cynical, with only roughly a fifth in each camp saying the economy is doing well.

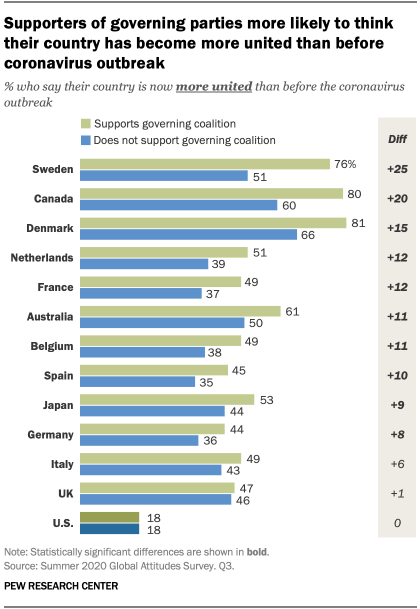

In most countries surveyed, governing party supporters are more likely to say their country is more united now than before the coronavirus outbreak. In Sweden, for example, about three-quarters of those who support the governing parties say their country is more united, while about half of those who do not support the governing parties say Sweden is now more united. Double-digit differences between governing coalition supporters and opponents also appear in Canada, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Australia, Belgium and Spain.

This is one question on which Republicans and others in the U.S. hold similar opinions: Large majorities of both groups say the U.S. is now more divided than before the coronavirus outbreak. This is in stark contrast to most of the other countries surveyed, though consistent with past findings in the U.S. showing broad pessimism about the country’s divisions. The assessment of national unity is not a partisan affair in Italy or the UK either, with no significant differences between governing party supporters and detractors in either country.

Note: The questions used for this analysis, along with their responses, can be found here and here. Here is how we developed the governing party variable, and the survey methodology.