Republicans will kick off the 119th Congress with a five-seat majority in the U.S. House of Representatives – the smallest margin of control in modern history. Their grip could become even more tenuous as three Republican seats are expected to be vacant in early 2025 until special elections are held.

Republicans’ majority in the Senate is set to be lean as well. They’ll hold 53 of 100 seats, with a potential tiebreaking vote from incoming Vice President JD Vance.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to understand how the size of congressional majorities has changed over time.

The analysis uses archival records from the historical offices of the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate.

We began our analysis in the 88th Congress (1963-65), the first Congress with 435 representatives and 100 senators. The data for which party held a majority in a Congress reflects the initial election results going into the term; it does not take into account any shifts during that session.

Independent lawmakers who caucus with a party are factored into determining the majority, as is a tiebreaking vote from the vice president in the Senate.

A party usually needs at least 218 seats for a majority in the House, but the number can be lower due to vacancies.

The first-day count for the 119th House includes Republican Reps. Elise Stefanik and Michael Waltz, who both won reelection but are likely to vacate their seats in January for posts in the Trump administration. The count also includes former GOP Rep. Matt Gaetz, who recently resigned from the 118th Congress. He has said he does not plan to return, even though he won reelection to the 119th Congress.

The count for the 119th Senate includes incoming Vice President JD Vance of Ohio and secretary of state nominee Marco Rubio of Florida, both of whom are expected to resign to join the Trump administration. Republican governors in these states will appoint replacements to serve until the next election.

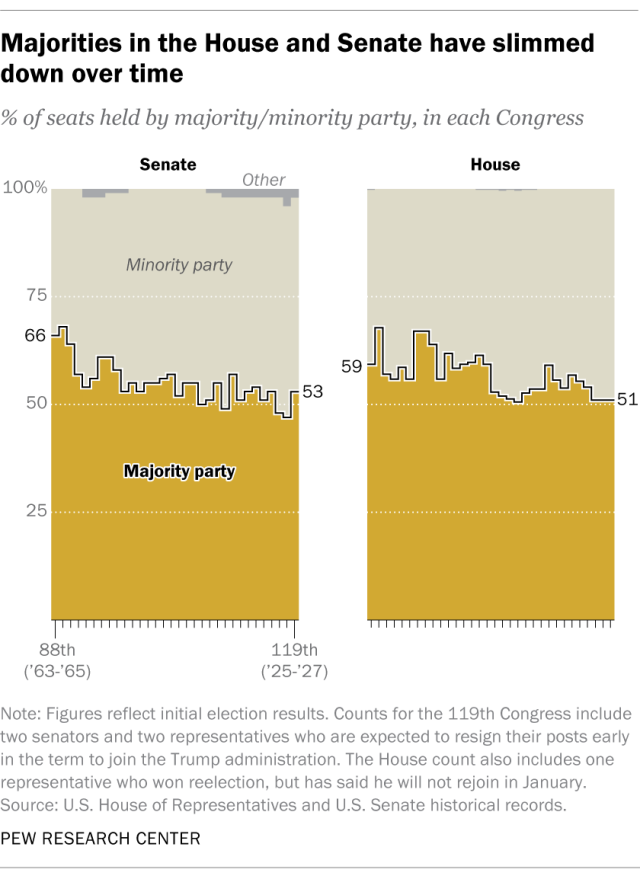

Narrow partisan divides in the House and Senate have become the norm in recent decades, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of historical data going back to the 88th Congress (1963-65), the first Congress with 435 representatives and 100 senators. This analysis reflects the initial election results for each Congress and does not factor in any shifts during the session.

The largest majorities in the House and Senate during this stretch occurred in the 1960s. Both belonged to Democrats.

- Democrats held 68% of House seats in the 89th Congress (1965-67).

- Democrats held 66% of Senate seats in the 88th Congress (1963-65).

Since then, the size of the majorities in both chambers has generally trended downward. By the late 1990s and early 2000s, the partisan split in both chambers hovered around 50-50.

In the House

House Republicans will hold 220 seats in January, giving them a five-seat majority. That will be the smallest in modern history by number of seats. The second-smallest majority came at the start of the 107th Congress (2001-03), when Republicans had a seven-seat majority. That Congress included two independent representatives – one who caucused with each party.

Looked at another way, House Republicans will have 50.6% of the seats in the upcoming 119th Congress – matching their majority in the 107th Congress. (The incoming Congress will not have any independent representatives, while there were two in the 107th.)

Razor-thin House margins have been common recently: The 117th and 118th Congresses each started off with 51.0% majorities, first for Democrats and then for Republicans.

In the Senate

Republicans will also have a relatively slim majority in the upcoming Senate, with 53 seats. This count includes the seats held by Vance of Ohio and fellow Republican Marco Rubio of Florida, who is expected to step down in the new year to join the Trump administration. GOP governors in both states will appoint replacements to serve until the next election.

Since the 88th Congress of 1963-65, there have been four other Senates where the majority party held 53 seats and eight Senates with a majority narrower than that. Most of these instances have come in the 21st century.

In some cases, the majority can hinge on which party independents caucus with or the vice president’s tiebreaking vote.

In the current 118th Congress, Democrats have the smallest Senate majority in modern history, with just 47 seats. They have the edge thanks to four independent senators who all caucus with Democrats and a tiebreaking vote from Vice President Kamala Harris.

Democrats in the 117th and 110th Senates also held tight majorities, with 48 and 49 seats, respectively. As in the current Congress, independent senators and a tiebreaking vice presidential vote gave Democrats the majority.

Only one Senate has ever begun with a 50-50 split between Republicans and Democrats. In the 107th Congress (2001-03), each party held exactly half the seats. GOP Vice President Dick Cheney’s tiebreaking vote gave Republicans the majority that Congress.

Breaking Senate ties

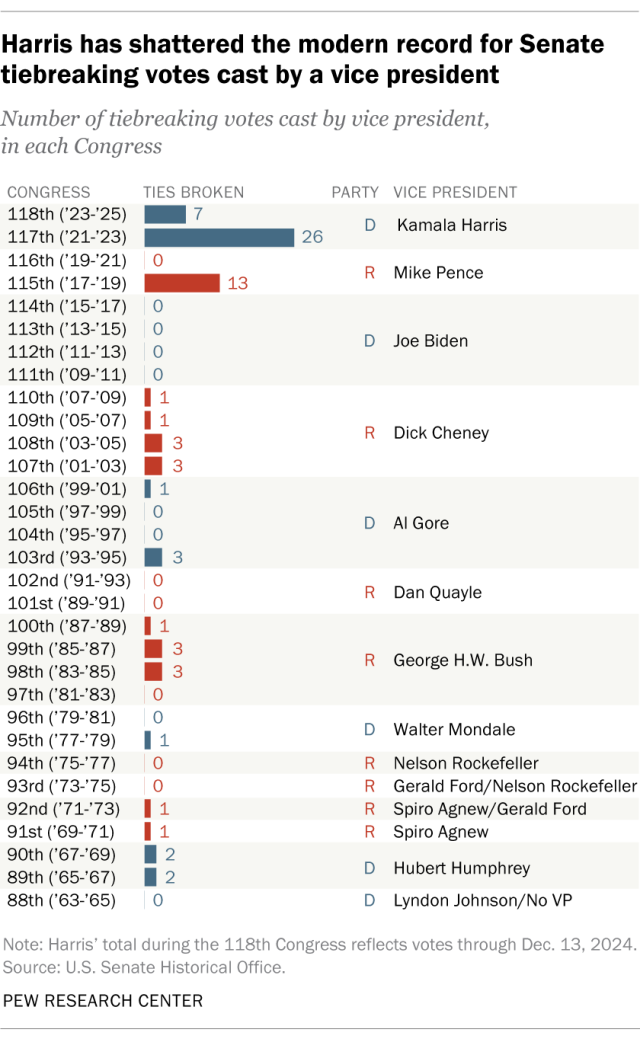

Recent narrow majorities in the Senate have resulted in a record number of tiebreaking votes from the vice president. Since taking office in 2021, Harris has cast 33 tiebreaking votes, far more than any vice president in the modern era of the Senate.

Harris cast 26 of her tiebreaking votes during the 117th Congress (2021-23) and seven during the 118th Congress.

The previous high for ties broken in a single Congress was 13, by Mike Pence in the 115th Congress (2017-2019). Before Pence, the most ties ever broken in one Congress was three. Just three vice presidents ever broke this many:

- Dick Cheney (107th Congress in 2001-03, 108th Congress in 2003-05)

- Al Gore (103rd Congress in 1993-95)

- George H.W. Bush (98th Congress in 1983-85, 99th Congress in 1985-87)

Harris and Pence served as vice president during periods with razor-thin Senate majorities. Harris presided over two of the narrowest Senate margins in history. And Republicans held just 51 Senate seats when Pence assumed the vice presidency.

President Joe Biden, who served for eight years as Barack Obama’s deputy, did not cast any tiebreaking votes when he was vice president.

The long-term narrowing of congressional majorities has come amid growing partisan polarization in the United States. It has also created more opportunities for partisan control to flip. For example, Democrats held the House from the 1960s until the 1994 midterms, when Republicans secured the majority. In just the last 20 years, by comparison, control of the House has changed hands four times.