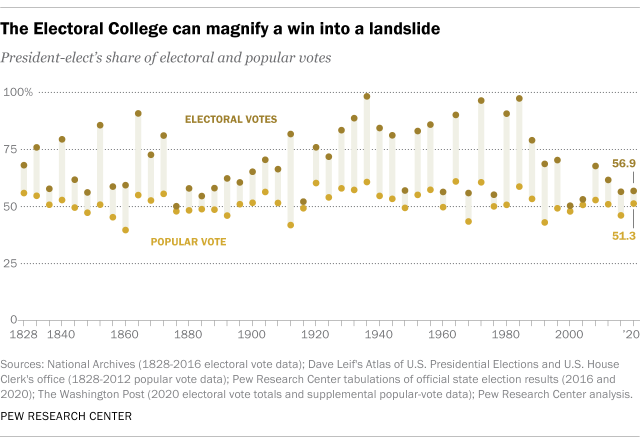

Democrat Joe Biden defeated President Donald Trump by about 4.45 percentage points, according to Pew Research Center’s tabulation of final or near-final returns from all 50 states and the District of Columbia. Biden received nearly 81.3 million votes, or 51.3% of all votes cast – a record, and more than 7 million more votes than Trump.

But when the 538 electors meet Dec. 14 in their respective states to cast the votes that will formally make Biden the president-elect, his margin of victory there likely will be greater than his margin in the popular vote. Barring any defections from so-called “faithless electors,” Biden is on track to receive 306 electoral votes, or 56.9% of the 538 total votes available.

Biden’s victory will be nearly identical to Trump’s Electoral College win in 2016, when Trump defeated Democrat Hillary Clinton 304-227 despite receiving 2.8 million fewer popular votes. (Two Republican electors and five Democratic electors cast “faithless” votes for other people.)

That two such dissimilar elections could generate such similar Electoral College margins illustrates an abiding feature of the United States’ quirky way of choosing its top executive: The Electoral College consistently produces more lopsided results than the popular vote.

This post builds on work Pew Research Center did following the 2016 presidential election, as well as a recent analysis of close state elections. We updated the electoral vote inflation (EVI) analysis in the 2016 post with results from this year’s Biden-Trump contest. EVI measures the disparity between the winner’s popular vote and electoral vote margins.

To determine the EVI, we first tabulated the votes cast in all 50 states and the District of Columbia, as reported by each jurisdiction’s chief election authority, to determine the popular vote margin. (In one state, for which no official 2020 results have yet been posted, we relied on The Washington Post’s vote tracker.)

For each election, we then calculated the share of all available Electoral College votes actually cast for each candidate. By dividing the winning electoral vote margin by the winning popular vote margin, we arrived at the EVI.

Looking back at every presidential election since 1828 (when they began to resemble today’s system), the winner’s electoral vote share has, on average, been 1.36 times his popular vote share – what we call the electoral vote inflation (EVI) factor.

The bigger the EVI, the greater the disparity between the winner’s popular vote and electoral vote margins; the smaller the EVI, the closer the two margins are to each other. Based on the reported popular vote to date and the expected vote in the Electoral College, Biden’s EVI is 1.11 – smaller, in fact, than Trump’s in 2016 (1.23), and the smallest since George W. Bush’s two victories in 2000 and 2004 (1.05 both times).

The EVI factor arises from two rules governing the Electoral College – one laid down in the Constitution and one that’s become standard practice over the decades. Under the Constitution, each state gets one electoral vote for each senator and representative it has in Congress. Since every state, no matter how big or how small, gets two senators, small states have greater weight in the Electoral College than they would based on their population alone.

Second, all but two states use a plurality winner-take-all system to award their presidential electors – whoever receives the most votes in a state wins all its electoral votes. Winning a state by 33 percentage points, as Biden did in Massachusetts, doesn’t get you any closer to the White House than winning it by 0.3 points (as Biden did in Arizona).

In contrast, consider the two states that don’t use winner-take-all, Maine and Nebraska. In those states, candidates get two electoral votes for winning the statewide vote plus one for each congressional district they win.

In Maine this year, Biden won 53.1% of the statewide vote and one of its two congressional districts, so he gained 75% of Maine’s electoral votes (three out of four), not 100%. In Nebraska, Trump took 58.2% of the statewide vote and two of three congressional districts, for 80% (four out of five) of the state’s electoral votes. While not really proportional, those results more closely reflect the diversity of candidate support within Maine and Nebraska than a winner-take-all system does.

For Trump in 2016 and Biden in 2020, winning a handful of large, winner-take-all states by very close margins proved key to their Electoral College victories. In 2016, Trump carried Florida, Michigan, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (total electoral votes: 75) by less than 2 percentage points each – or a combined total of 190,655 votes out of more than 23.3 million cast in those states. This year, Biden carried Arizona, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin (total electoral votes: 57) by that same narrow margin – or a combined total of 124,364 votes out of 18.6 million cast.

The biggest disparity between the winning electoral and popular votes, with an EVI of 1.96, was in 1912 in the four-way slugfest between Democrat Woodrow Wilson, Republican incumbent William Howard Taft, Progressive Theodore Roosevelt (who had bolted from the Republicans) and Socialist Eugene V. Debs. Wilson won a whopping 82% of the electoral votes – 435 out of 531 – with less than 42% of the overall popular vote. In fact, Wilson won popular vote majorities in only 11 of the 40 states he carried – all in what was then the solidly Democratic South.

The next biggest gap was the 1980 “Reagan landslide.” In that three-way contest, Ronald Reagan took just under 51% of the popular vote, to Jimmy Carter’s 41% and independent John Anderson’s 6.6%. But Reagan soared past Carter in the Electoral College: 489 electoral votes (91% of the total) to 49, for an EV inflation factor of 1.79.

Many of the elections with the most-inflated electoral votes featured prominent third-party candidates who held down the winners’ popular vote share without being significant Electoral College players themselves. On the other hand, when the two major-party nominees ran fairly evenly and there were no notable independents or third parties, the Electoral College vote has tended to be much closer to the popular tally.

Defenders of the Electoral College argue that the EVI is a feature, not a bug. As one observer wrote about the 1968 election, the system’s strength is in “delivering a clear, incontrovertible national decision from a messy and angry (and violent) campaign year.”

But many Americans favor changing the way we elect our presidents. A Pew Research Center survey from this past January found that 58% of U.S. adults favored amending the Constitution so the presidential candidate who receives the most popular votes nationwide wins; 40% preferred keeping the current system.