Post-general election meetings of Congress, which have become routine in recent decades, are commonly known as “lame-duck” sessions. The unflattering descriptor alludes to the senators and representatives who have lost reelection or whose terms are almost up but can still help make laws for a few more weeks.

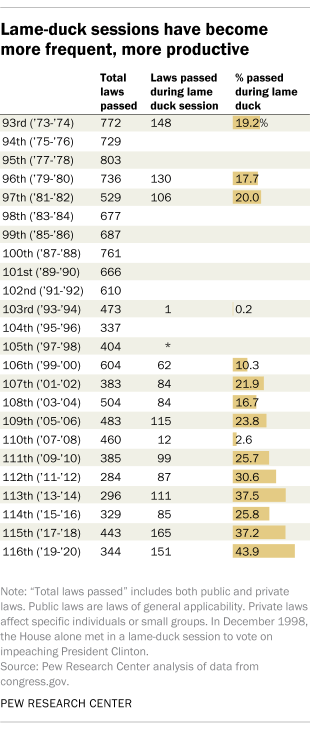

Lame-duck sessions historically were used to wrap up pending business, and more recently to cut last-minute budget deals. But none in the nearly five decades for which data is available has been as legislatively productive as the lame-duck session of the 116th Congress, which wrapped up on Jan. 3.

More than four-in-ten bills that became law out of the 116th Congress (151 of 344, or 44%) were passed in the final two months of its two-year term. That’s the highest share of lame-duck legislation since at least the 93rd Congress of 1973-74, the first years of our analysis. Among the bills enacted during the recent lame-duck session was a $900 billion economic relief bill that had been the subject of a congressional standoff for months leading up to Election Day.

This post is the latest in a series, starting in 2014, examining the productivity of Congress. Laws aren’t widgets, of course, and legislative productivity can be measured in many different ways – by counting the number of pages in the statute book, how many votes were taken, comparing bills introduced with bills enacted, and so on.

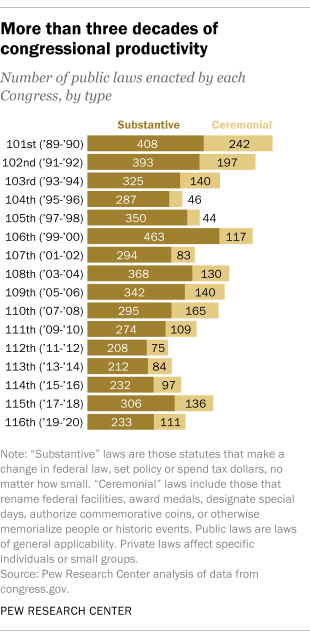

We’ve chosen a fairly straightforward approach: how many laws (public laws in most cases, as opposed to private laws that apply to single individuals) each Congress actually enacted. We also distinguish between substantive and ceremonial laws. In general, substantive laws are those that have some real-world impact, no matter how small – be it spending federal dollars, setting policy, adjusting the boundaries of a national park or merely correcting a typographical error in an earlier law.

Ceremonial laws are those intended primarily to honor or recognize an individual, group or cause – for example, naming or renaming post offices, courthouses and other federal facilities, authorizing commemorative coins or congressional gold medals, or authorizing outside groups to erect memorials on federal land. (In earlier years Congress also designated dozens of special days, weeks and months in honor of various causes, such as National Next Door Neighbor Day, Nicolaus Copernicus Week and National Arthritis Month. However, that practice was largely abandoned in the mid-1990s.)

As our source for laws enacted, we’ve relied on congress.gov, an online repository of legislative data and information maintained by the Library of Congress. Congress.gov goes back to the 93rd Congress (1973-74), so that’s where our analysis of lame-duck sessions starts. Our more detailed look at substantive vs. ceremonial laws begins with the 101st Congress (1989-90). For each Congress, we reviewed the text of each law passed to sort it into the appropriate category.

In most cases we refer to each Congress using the two calendar years that make up the bulk of the time each Congress is in session, though a Congress formally ends in the subsequent odd-numbered year (for example, the 115th Congress of 2017-18 concluded on Jan. 3, 2019).

Despite its late burst of activity, the 116th was overall one of the least legislatively productive Congresses of the past five decades. Of the 24 Congresses we analyzed, only four passed fewer laws than the 116th – three of them within the past decade.

The 116th Congress sent 353 bills to President Donald Trump’s desk, according to the Library of Congress’ congress.gov site. Trump vetoed 10 of them, and all but one of those vetoes was upheld or not challenged. (The exception was the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal 2021.) He signed the last of the remaining bills from the 116th Congress into law on Jan. 13.

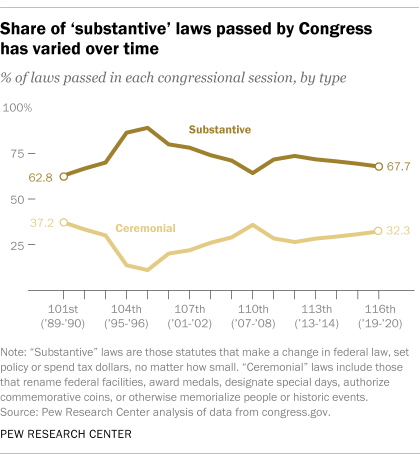

By our deliberately generous criteria, only about two-thirds of the laws enacted by the recently concluded Congress (68%) were “substantive” – meaning they changed written law, spent money or established policy, no matter how minor. Ceremonial laws – those that rename post offices and Veterans Affairs clinics, authorize commemorative coins and the like – accounted for nearly a third (32%) of legislative output, the highest rate since the 110th Congress of 2007-08. (Our analysis considers only public laws, which are laws of general applicability. Private laws, which affect specific individuals or small groups, typically are used to settle claims against the federal government or make an exception to agency policy in a particular case; their use has declined markedly in the past few decades, with only one enacted since 2013.)

Among the more significant legislation enacted by the 116th Congress were four major bills and several minor ones responding to the coronavirus pandemic; a major conservation and public-lands law; a free trade agreement between the United States, Canada and Mexico that replaces NAFTA; and a measure to reform the governance of Olympic sports so as to protect young athletes from abuse.

Of course, the 116th Congress did have its distractions – an impeachment, a pandemic, a contentious election and its even more contentious aftermath. And much of the 116th’s relatively low level of productivity may be due to conflicts between the Democratic-majority House and the Republican-run Senate (not to mention those between Congress and Trump). In the 115th Congress of 2017-18, by comparison, Republicans controlled both legislative chambers and passed 442 laws, 69% of them substantive.

Other factors that likely helped hold down the 116th Congress’ output include the senatorial filibuster, which effectively means all but the least controversial measures need a 60-vote supermajority to move forward. Another potential factor is the long-term trend of bills growing in length as they shrink in number. The 84th Congress of 1955-56, for example, enacted more than 1,000 public laws, but they averaged fewer than two pages apiece, according to the Brookings Institution’s Vital Statistics on Congress database. By contrast, the 442 laws enacted by the 115th Congress of 2017-18 averaged nearly 18 pages each. (Vital Statistics doesn’t yet have final figures for the 116th.)

It’s also become more common for Congress to pass mammoth “omnibus” or “consolidated” bills that bundle multiple smaller and largely unrelated bills in one “must-pass” package. Last month, for instance, Congress passed the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021, which at nearly 5,600 pages in draft form was one of the longest pieces of U.S. legislation ever passed. It contained dozens of measures that in years past would have stood alone, among them 12 appropriations bills, a new coronavirus relief package, a pipeline safety law, the annual intelligence authorization act, and a raft of water development projects. It also included bills on energy policy, intellectual property and aircraft safety, foster youth and families, simplifying the process of applying for federal student aid, and much, much more – including 27 pages of “extensions and technical corrections” to other laws.

Lame-duck sessions, meanwhile, weren’t especially common before the 2000s, and when they did occur, they typically accounted for about a fifth of a given Congress’ legislative output. (The 1994 lame duck was held for just one purpose: considering a bill to approve and implement the Uruguay Round trade agreement, which led to the creation of the World Trade Organization.)

Since 2000, however, there’s been a lame-duck session at the end of every Congress, and they’ve gradually accounted for more and more of the legislature’s output. The 2014-15 lame-duck session, which ran almost to the end of the 113th Congress’ term, generated 38% of that Congress’ entire corpus of laws – second only to the late output of the just-concluded 116th.