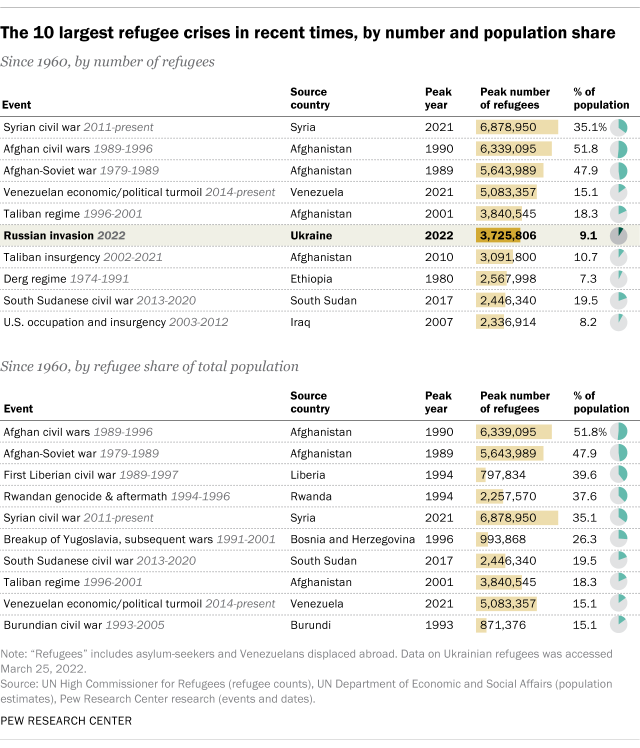

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created one of the biggest refugee crises of modern times. A month into the war, more than 3.7 million Ukrainians have fled to neighboring countries – the sixth-largest refugee outflow over the past 60-plus years, according to a Pew Research Center analysis of United Nations data.

There are now almost as many Ukrainian refugees as there were Afghan refugees fleeing the (first) Taliban regime in 2001, according to figures compiled by the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). They represent about 9.1% of Ukraine’s pre-invasion population of about 41.1 million – ranking the current crisis 16th among 28 major refugee crises by share of population.

The Center examined all cases in the UNHCR’s database since 1960 where there were at least 500,000 refugees and similarly displaced people from a given country in a given year. The analysis doesn’t include “internally displaced persons” – those who have fled or been forced from their usual homes but haven’t yet crossed an international border. (Earlier this week, UNHCR head Filippo Grandi estimated that, all told, 10 million Ukrainians – nearly a quarter of the population – had been displaced either internally or externally by the war.)

This post aims to put the massive outflow of Ukrainians fleeing the invasion of their country by Russian forces in the context of other major refugee crises in recent decades.

The terminology surrounding refugees and other displaced people can be confusing, not to mention counterintuitive. The definition of “refugee” in U.S. law mirrors that in the 1951 United Nations convention that governs international treatment of refugees. The convention defines a refugee as someone who is outside the country of his or her nationality and is unable (or unwilling) to return to it, or avail himself or herself of its protection, due to a “well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.”

Whether or not someone qualifies as a refugee typically is determined by either the country they’ve fled to or by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Until that determination is made, a displaced person asking for international protection is termed an “asylum seeker.” We included asylum seekers in our refugee counts.

For Venezuela, we also included a special UNHCR category called “Venezuelans displaced abroad” – essentially, people who have fled Venezuela’s political and economic turmoil and who have either found some means other than acquiring refugee status to legally remain in another country, or who are living in another country without legal permission or formal protection and haven’t applied for refugee status.

Because we chose to focus on refugees and others who have fled their home countries, we did not include “internally displaced persons” in our analysis. These are people who have been forced to flee their usual place of residence due to “armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters” but who have not crossed any international borders.

Our main source for counts of refugees, asylum seekers and similar groups was the UNHCR’s “Refugee Data Finder” application, which generally has country-specific data from the 1960s to the present. The agency also has a webpage specifically about the crisis in Ukraine, from which we drew the count of refugees from that country. The estimated population of Ukraine on Feb. 1 (excluding Crimea, which was illegally annexed by Russia in 2014) was 41,130,432, according to the country’s census agency. Historical population estimates for other countries came from the UN’s Department of Economic and Social Affairs.

For each country in the UNHCR’s database, we identified years in which there were at least 500,000 refugees and asylum seekers from that country. Since in most cases those years were part of longer wars or other crises, we grouped them into 28 distinct refugee-creating events. For each multiyear event, we took the year in which there were the most refugees and asylum seekers, then divided that figure by the country’s total population for that year.

Syria’s civil war, which began in 2011, has created more refugees than any other crisis since the early 1960s, when UNHCR began keeping data on individual countries. Nearly 6.9 million Syrians – about a third of the country’s prewar population – are living as refugees or asylum-seekers outside their home country, with almost 3.7 million now in Turkey. An additional 6.8 million Syrians have been displaced from their homes but are living elsewhere in the country – meaning the civil war has uprooted about two-thirds of Syria’s entire population.

Afghanistan, which has been at war either with itself or with outside forces for more than four decades, has had more than 2 million refugees every year since 1981. The peak year was 1990, after Soviet troops had withdrawn from the country and the USSR-backed government was battling to hang onto power against a coalition of mujahedeen groups. That year, more than half the country’s total estimated population – 6.3 million people – were listed as refugees.

Venezuela has also seen massive population outflows over the past several years as the country’s economy has all but collapsed, its government has cracked down on dissent, and opposition efforts to unseat President Nicolas Maduro’s government have stalled. According to the UNHCR, more than 5 million Venezuelans are refugees in other countries, are seeking asylum, or have been otherwise displaced abroad – all told, about 15% of the current estimated population.