Nearly three years into a pandemic that has tightened the supply of affordable housing in the United States, 60% of Americans say they’re very concerned about the cost of housing, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in October. Rising housing costs have hit renters hard during this span – and prices have continued to soar over the past year, making rent control and other related proposals prominent issues in the recent midterm elections.

Here are some key facts about U.S. renters and the problems they have faced with housing affordability during the COVID-19 pandemic, based primarily on a Center analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to share key facts about U.S. renters and their experiences with housing affordability during the pandemic. It draws primarily on 2021 data – the most recent data available – from the American Housing Survey (AHS). The AHS is sponsored by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development and conducted biennially from May to September by the U.S. Census Bureau. It collects data on the size, composition and quality of the nation’s housing, as well as on the demographic and income characteristics of U.S. homeowners and renters. AHS collects data on the household, using the household head as the survey reference person. Read the AHS’s methodology for more information on how the survey is conducted. The Census Bureau’s own research shows that it has long undercounted Black, Latino and some other population groups, which could mean they are underrepresented in the demographic statistics in this post.

This analysis also includes public opinion data from a Center survey conducted in August 2020. Everyone who took part in the survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

More information about the survey question and methodology can be found via the links in the text.

Nearly 46 million households rented their homes in 2021. Renters accounted for more than a third of all households in the U.S., while homeowners accounted for nearly two-thirds, according to data from the Census Bureau’s 2021 American Housing Survey (AHS). The number of renters in 2021 was higher than a decade ago.

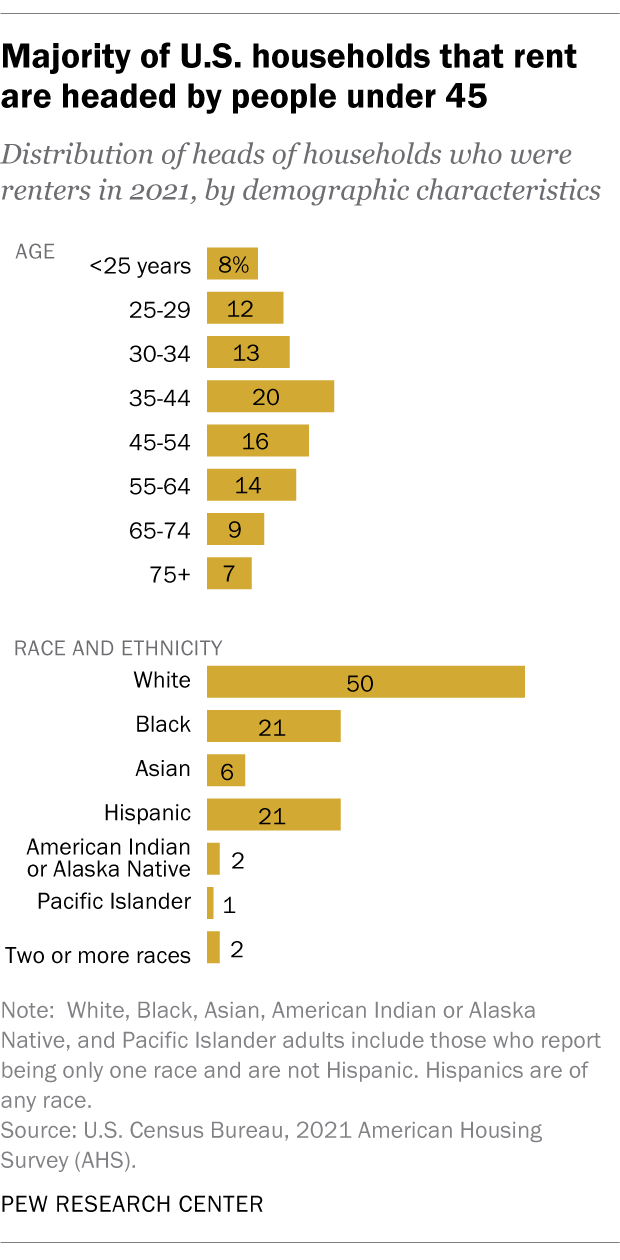

Relatively large shares of Americans who are younger, Black or Hispanic rented during the pandemic. A third of renting households were headed by someone under the age of 35; an additional 20% were ages 35 to 44, according to AHS data. The median age was 43 for renters in 2021, compared with 57 for homeowners. The median age of household heads overall was 53 that year.

Black and Hispanic adults made up a disproportionately large percentage of renters (21% each) compared with their overall shares of the U.S. population (12% and 19%, respectively). Still, the largest share of renters – half in 2021 – were non-Hispanic White.

A majority of renters lived with someone else, and two-bedroom arrangements were the most common. Household heads who rented were more likely to live with at least one other person than to live alone in 2021 (62% vs. 38%), according to AHS data. The largest share of renters who lived with other people (42%) were married couples living alone or with children or other family.

Among households who rented, 40% lived in two-bedroom housing, while about a quarter each lived in one-bedroom (27%) or three-bedroom accommodations (24%).

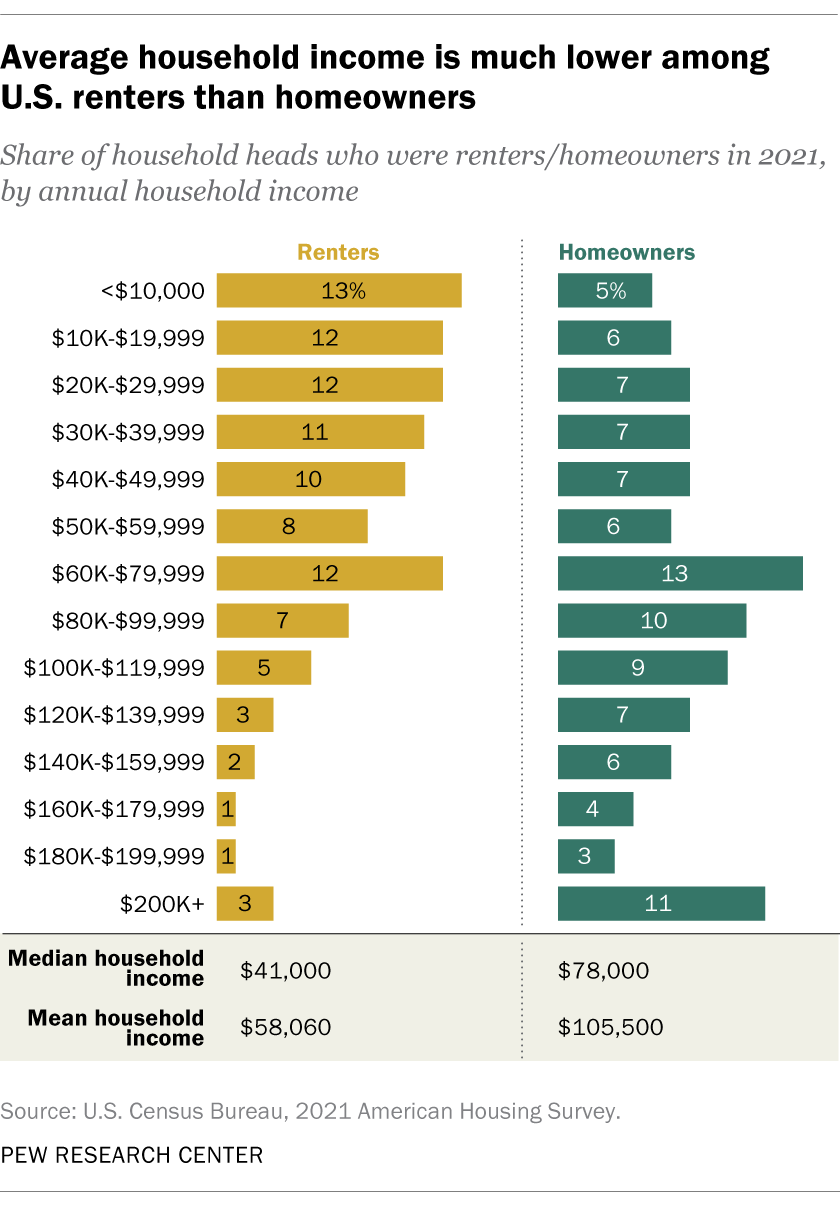

Renters tended to have much lower household incomes than homeowners. The median household income for renters was $41,000 in 2021, compared with $78,000 among homeowners. A majority of renters (57%) had annual household incomes of less than $50,000 that year.

The median monthly cost of rent alone increased 12% since before the pandemic, from $909 in 2019 to $1,015 in 2021, according to AHS data. By comparison, overall inflation was about 6% during this span.

The AHS estimates that about half of rental households (51%) spent $1,000 or more a month on rent in 2021 – up from 44% in 2019.

Renters in some metro areas faced especially sizable rent increases during the pandemic. Of the largest 15 metropolitan areas the Census Bureau’s AHS covers, eight saw increases of 10% or more in median monthly rent between 2019 and 2021. The median monthly cost of rent rose the most in Atlanta (17%), from $1,025 in 2019 to $1,200 in 2021.

Overall, the San Francisco metro area had the highest median monthly rent ($2,065) in 2021, followed by Los Angeles ($1,650), Washington, D.C. ($1,629) and Boston ($1,600). The New York City and Seattle metro areas were tied for the fifth-highest median monthly rent ($1,500).

Metropolitan areas were already seeing rent hikes before the COVID-19 outbreak. In 10 urban areas, median monthly rent increased 10% or more between 2017 and 2019. Riverside, California, and Phoenix, Arizona, saw the largest increases during that span (18%).

Some metropolitan renters reported housing inadequacies in 2021, when many Americans were spending more time at home. In the Houston and New York City metro areas, 14% of renter households said they had severely or moderately inadequate housing. (The AHS uses certain criteria – such as issues with plumbing, heating, electricity, wiring, upkeep or other problems – to classify this measure.) About one-in-ten renters in Dallas (11%) and 9% each in Boston and Washington said the same.

Some Americans struggled to pay rent early in the coronavirus outbreak. Around one-in-six U.S. adults (16%) said in an August 2020 Center survey that they had problems paying their rent or mortgage since the U.S. coronavirus outbreak started that February. Black (28%) and Hispanic (26%) adults were especially likely to report they struggled to pay for rent or a mortgage during this time; 11% of White adults said the same. Around a third of Americans with lower incomes (32%) also said they faced this issue.

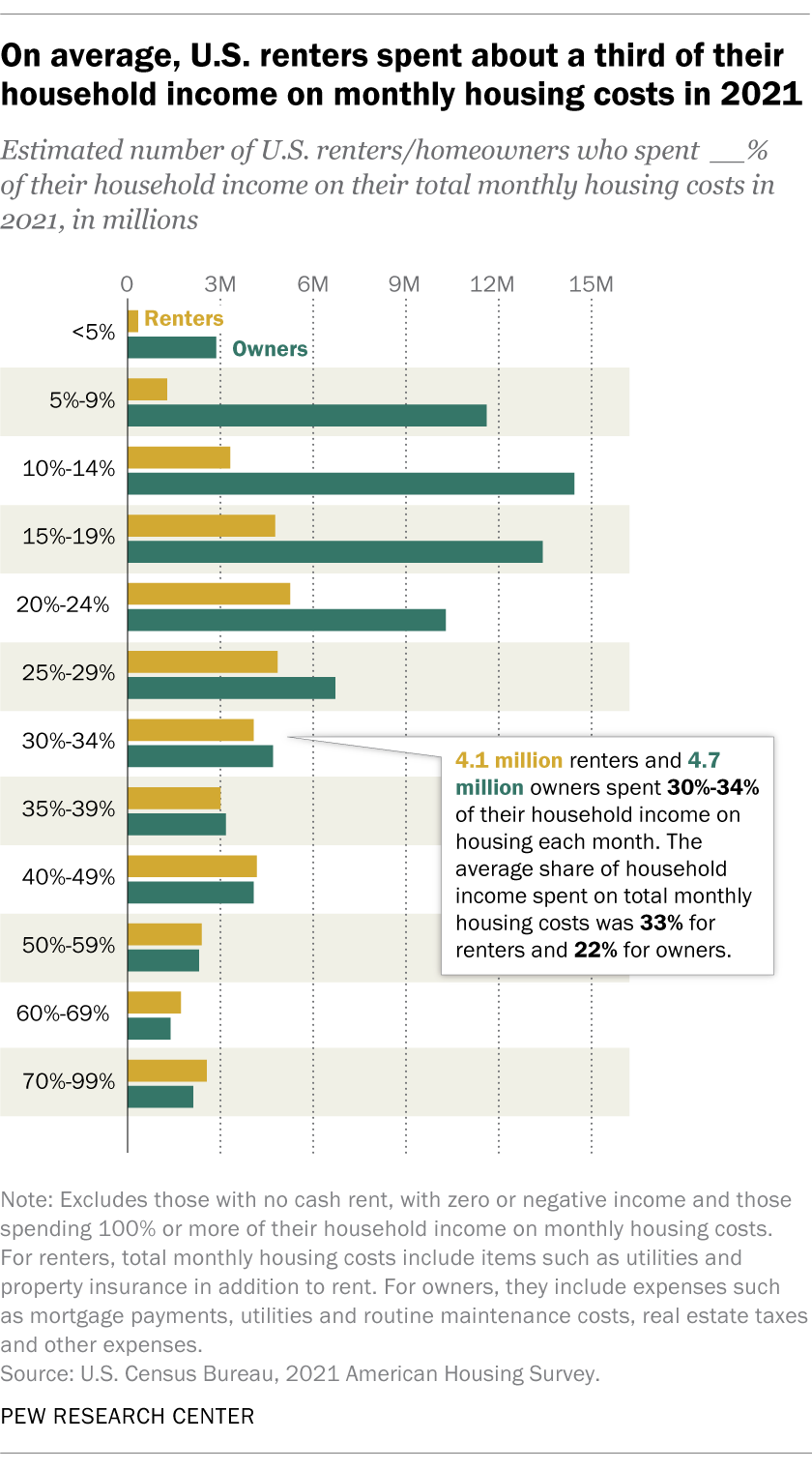

Renters spent a greater share of their household income on housing costs than homeowners did. The median percentage of household income that renters spent on their total monthly housing costs in 2021 – as defined by the AHS – was 29%, compared with 18% for homeowners. For renters, total monthly housing costs include items such as utilities and property insurance in addition to rent. For owners, costs include mortgage payments, utilities and routine maintenance costs, real estate taxes and other expenses.

Nearly four-in-ten renters spent 30% or more of their household income on their total monthly housing costs, including 15% who spent half or more of their income on this. This meets the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s definition of being “cost burdened.” Although spending 30% of income on housing has long been considered the most a household should spend to still have money left over for essentials, some researchers have argued this measure should be adjusted to reflect different types of households, changes in the cost of additional necessities, and other factors.

Even before the pandemic, renters were spending substantial shares of their income on housing. In 2019, the median share of income that households who rent spent on their total monthly housing costs was 28%, according to AHS data.

Since much of renters’ household income already goes toward housing costs, rent increases can potentially push those at the lower ends of the income spectrum completely out of the market. A 2020 analysis from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that a $100 increase in median rent was associated with a 9% increase in the estimated homelessness rate – even after factoring in other relevant factors such as changes in wages and the unemployment rate.

While the federal government’s national eviction moratorium protected renters during earlier stages of the coronavirus outbreak, the policy has since ended, and eviction filings have reportedly risen in recent months. Other state- and city-wide pandemic-related tenant protections are now expiring in Los Angeles and Oregon. And in New York City, tenants in rent-stabilized apartments are facing rent increases.