Most of the publics in the 14 nations included in the survey are dissatisfied – some by overwhelming margins – with the way things are going in their countries, and majorities in all see their economies as struggling. In most of the Eastern European and former Soviet countries surveyed, people see their nations plagued by corruption, crime and illegal drugs.

Despite some common perceptions about what they view as major national problems, the publics in the former Soviet bloc see their leaders in very different lights. For example, despite broad dissatisfaction with current conditions, 70% of Bulgarians say they approve of the performance of their new prime minister, Boiko Borisov, who took office in July. At the same time, 83% of Ukrainians disapprove of the job being done by their president, Viktor Yushchenko, the country’s leader during a time of economic trouble and continuing tensions with neighboring Russia.

Broad Dissatisfaction With National Conditions

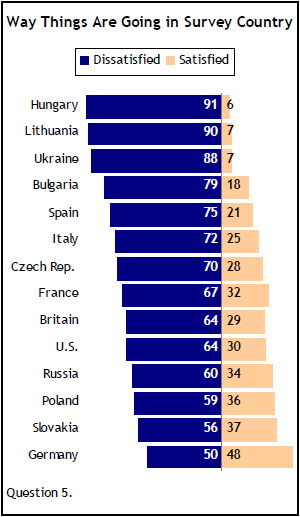

Majorities in 13 of the 14 nations surveyed are dissatisfied with the way things are going in their countries. Dissatisfaction is pervasive among several Eastern European publics – Hungary (91%), Lithuania (90%), Ukraine (88%) and Bulgaria (79%). But it is also high in Western Europe, particularly in Spain (75%) and Italy (72%).

Two-thirds of those in France (67%), and 64% each in the United States and Britain also say they are dissatisfied, compared with 60% in Russia, 59% in Poland and 56% in Slovakia. Germany is the one country without a clear majority saying they are dissatisfied, though there is a gap between those in the former East Germany and those in the former West Germany. As a whole, 50% say they are dissatisfied, while 48% say they are satisfied. In the east, 56% say they are dissatisfied; 41% say they are satisfied. The west more closely reflects the nation as a whole: 49% on each side of the equation.

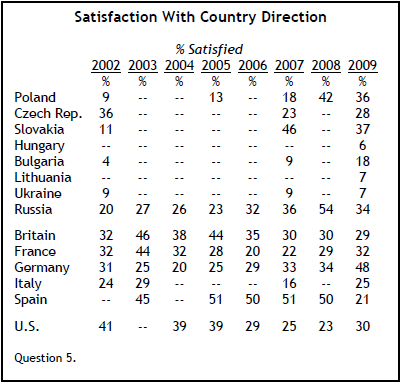

While the survey comes as many nations are grappling with the effects of the recent economic meltdown, the levels of satisfaction among former Eastern bloc nations, in most cases, have changed little or even increased since 2007. For example, in Poland, 36% say they are satisfied with the way things are going there, up from 18% in 2007 and 9% in 2002. In Bulgaria, a relatively low 18% say they are satisfied, but that is up from 9% in 2007 and 4% in 2002.

In Germany, 48% say they are satisfied, compared with 33% that said the same in 2007 and 31% in 2002. In 2007, 35% of those in the west said they were satisfied with the country’s direction, compared with 23% in the east. In 2002, the gap was slightly wider: 35% of those in the west said they were satisfied, compared with 18% in the east.

Publics in other former communist nations show little or no change in recent years. In Ukraine, just 7% say they are satisfied with their country’s direction, compared with 9% in 2007 and 2002. In the Czech Republic, 28% say they are satisfied, up slightly from 23% in 2007, but down from 36% in 2002.

In the current survey, Slovaks give their country one of the higher levels of satisfaction (37%). That is down from 46% in 2007, but up significantly from 11% in 2002. In Russia, 34% say they are satisfied, about the same as the 36% who said the same in 2007, but that is up from the 20% who said they were satisfied in 2002.

Among Western European nations, Spain shows a big drop in satisfaction, going from 51% in 2007 to 21% now, while the level in France increased from 22% in 2007 to 32%. The current level matches the 32% recorded in 2002. In Italy, 25% say they are satisfied, compared with 16% in 2007 and 24% in 2002. In the United States, 30% now say they are satisfied, compared with 25% in 2007 and 41% in 2002.

Troubled Economies

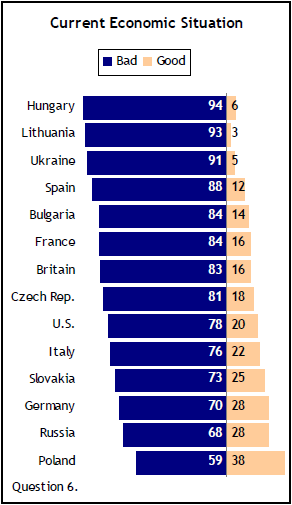

Majorities in all of the countries surveyed say the economic situation in their nation is bad. In several of the Eastern European and former Soviet nations, negative evaluations are nearly universal, including Hungary (94%), Lithuania (93%) and Ukraine (91%). Large majorities in the Western European countries also rate their economies as bad.

In those cases where there are trends, positive economic ratings have declined, in most instances significantly, since the spring of 2007, before the start of the current economic downturn. The one exception is Poland, where there has been no change compared with two years ago: 38% currently view the economic situation there positively, compared with 36% in 2007. That is up sharply from 7% rating the economy as good in 2002.

In several other countries where comparative data is available, the trends have been negative. In 2007, 19% of Ukrainians gave their country’s economy a positive evaluation; today, just 5% do so. There have been larger declines in positive views of the economies in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Germany. In the Czech Republic, 18% describe the economy as good, down from 41% in 2007. In Slovakia, the percentage giving the economy a good rating dropped from 53% in 2007 to 25% this fall. In Germany, 63% gave the economy a positive rating in 2007; 28% do so today.

The 35-point decline in positive economic views in Germany is comparable to the 30- point drop in the United States; in 2007, 50% of Americans gave the economy a positive rating compared with just 20% today. In Britain, the decline has been even greater: from 69% in 2007 to 16% today, a decline of 53 points.

Corruption, Crime Viewed as Major Problems

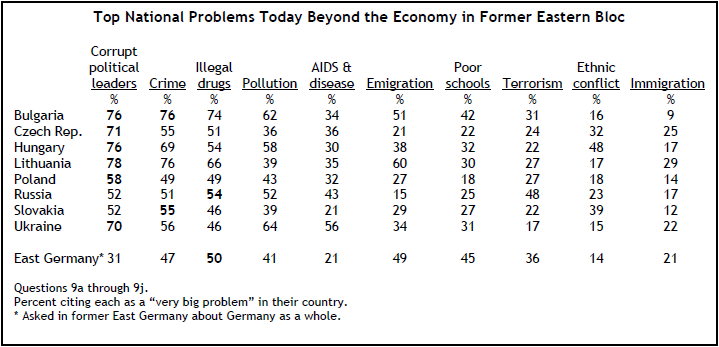

Majorities in most of the Eastern European and former Soviet nations surveyed say that corrupt leaders are a very big problem in their country. The one exception is former East Germany, where 31% see such corruption as a very big problem for Germany. Large percentages in most of the nations also see crime and illegal drugs as very big problems within their borders.

In some nations, concerns about corruption have eased somewhat since 2002. Currently, 58% in Poland say they see corrupt leaders as a very big problem, compared with 70% who said the same in 2002. In Slovakia, there has been a drop from 79% in 2002 to 52%, while in Russia the percentage fell from 61% to 52%. And among those in what was East Germany, the percentage that says corrupt leaders are a very big problem is down 12 points from 43% in 2002.

Elsewhere, though, corruption concerns have grown. In Bulgaria, 76% now say corrupt leaders are a very big problem, up from 60% in 2002. The increases are smaller in Ukraine (63% to 70%) and the Czech Republic (65% to 71%). Though there are no trends for Lithuania and Hungary, large majorities in both (78% and 76%, respectively) say corrupt leaders are a very big problem in their country.

Majorities in each of the nations except Poland also say that crime is a very big problem, with the highest percentages in Bulgaria (76%), Lithuania (76%) and Hungary (69%). The proportion saying crime is a very big problem is up significantly in Bulgaria from 60% in 2007. In 2002, 72% of Bulgarians said they saw crime as a serious problem.

Crime concerns have declined since 2002 in the other Eastern European nations where trend data is available. For example, 80% in Poland said they saw crime as a very big problem that year, compared with 49% today. In the Czech Republic, the percentage dropped from 66% in 2002 to 55%, similar to the drop in Ukraine (from 66% to 56%). Perceptions of crime as a very big problem in Russia have declined, going from 75% in 2002 to 51% this fall. In Slovakia, the percentage has fallen from 71% in 2002 to 55%. In the former East Germany, there has been no change since 2002, with 47% in each survey saying they think crime is a very big problem.

The publics in Bulgaria (74%) and Lithuania (66%) are most likely to say that illegal drugs are a very big problem, though close to half in each of the other countries surveyed agree. In Russia and the Czech Republic, there has been a 10-point decline since 2007 in the percentage saying drugs are a very big problem. Just over half of Russians (54%) and Czechs (51%) now say this is a very big problem for their country.

More than six-in-ten Ukrainians (64%) and Bulgarians (62%) say pollution is a very big problem for their country. Hungarians are not far behind at 58%. Views in Ukraine and Bulgaria are little changed from 2007, but, in the same time period, the percentage of Russians who say pollution is a very big problem has fallen from 61% to 52%, and the percentage of Slovakians expressing this view fell has declined 52% to 39%.

The spread of HIV/AIDS and other infectious diseases is less of a concern in most of the Eastern European nations, though almost six-in-ten (56%) in Ukraine say the spread of infectious diseases is a very big problem. Still, that is down from 66% in 2002. Concern in Russia has shown a larger decline, dropping from 63% in 2002 to 43%.

Among the nations in the survey, Lithuanians express the greatest concern about people leaving their country for jobs elsewhere, with six-in-ten (60%) saying that this is a very big problem. About half of Bulgarians (51%) agree, but the publics in the other nations generally see emigration as less of a problem.

A higher percentage of Russians voice concerns about terrorism than in the other nations; 48% say terrorism is a very big problem. But that is down from 65% in 2002. A large decline in recent years is also evident among Poles: 27% now see terrorism as a very big problem, compared with 45% in 2002. Among people in the former East Germany, the percentage that rank terrorism as a very big problem has dropped from 48% to 36%. But concerns over terrorism have increased in Bulgaria, where 31% now say terrorism is a very big problem, up 10 points from 2002.

More than four-in-ten Bulgarians (42%) and east Germans (45%) say the poor quality of schools is a very big problem in their country, higher than other nations in the survey and in both cases up from the percentage that cited school quality as a very big problem (23% and 38%, respectively) in 2002. Meanwhile, concerns about schools have dropped significantly since that time in the Czech Republic (41% then to 22%) and Slovakia (50% then to 27%).

Close to half of Hungarians (48%) say conflicts between ethnic and nationality groups are a very big problem in their country. Just to the north, about four-in-ten in Slovakia (39%) say conflicts between nationality groups are a very big problem in their country, possibly reflecting tensions over a new language law seen by the nation’s ethnic Hungarians as discriminatory. Just 26% of Slovaks cited this as a very big problem in 2002; two-in-ten said it was a very big problem in mid-2007. In Russia, the percentage citing ethnic or nationality conflicts as a very big problem has dropped from 41% in 2002 to 28% in 2007 to 23% this year. In east Germany, that percentage has also dropped, from 32% in 2002 to 14% this year.

Relatively small percentages in each of the Eastern European and former Soviet nations rate immigration as a major problem. About three-in-ten (29%) Lithuanians say they see immigration as a very big problem in their country, the largest percentage in the survey. At the other end of the spectrum, just 9% of Bulgarians and 12% of Slovaks say immigration is a very big problem.

Mixed Ratings for National Leaders

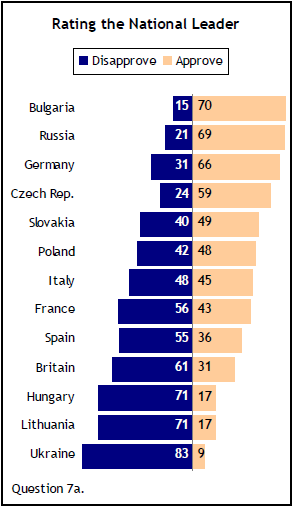

Majorities in only four of the publics surveyed – Bulgaria, Russia, Germany and the Czech Republic – approve of the way their government’s leader is handling the job.

Approval ratings for the leaders in the Eastern European range from a high of 70% for new Bulgarian Prime Minister Boiko Borisov to just 9% for Ukrainian President Viktor Yushchenko. And with the exception of German Chancellor Angela Merkel (66%), all of the ratings for Western European leaders are more negative than positive.

About seven-in-ten Russians (69%) say they approve of the way the current head of state, President Dmitri Medvedev, is handling his job. Even more (78%) say they approve of the job being done by his predecessor and the current prime minister, Vladimir Putin.

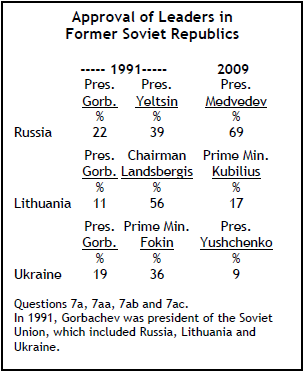

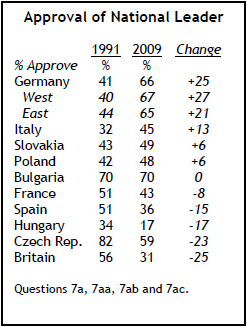

Today’s Russian leaders get much higher approval ratings than their predecessors in 1991, during the final days of the Soviet Union. Until the end of that year, Mikhail Gorbachev was president of the Soviet Union, and Boris Yeltsin was president of the Russian Republic. At that time, just 22% of Russians approved of Gorbachev’s job performance, while 39% said they approved of the way Yeltsin was handling his job.

Today, only small percentages approve of the way Ukraine’s Yushchenko (9%) or Lithuanian Prime Minister Andrius Kubilius (17%) are handling their jobs. The numbers are down from 1991, when 36% approved of the job being done by Vitold Fokin, the prime minister of the Ukrainian Republic at the time, or Vytautas Landsbergis, who was the chairman of the Supreme Council of Lithuania.

At that time, Lithuanians and Ukrainians showed little support for Gorbachev (11% and 19% approval, respectively) in his role as president of the Soviet Union.

Meanwhile, Germans – both in the west and the east – rate Merkel’s performance more highly than they did Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s in 1991. Today, about two-thirds of Germans (66%) say they approve of the way Merkel is handling her job with little difference between the west (67%) and the east (65%). In 1991, about four-in-ten (41%) Germans approved of Kohl’s performance – 40% in the west and 44% in the east.

Approval ratings for the leaders of Britain, France and Spain are down from 1991. Currently, 31% approve of British Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s job performance, compared with 56% for John Major’s in 1991, 36% approve of Spain’s Prime Minister José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero; in 1991, 51% approved of Felipe González’s job performance; and French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s 43% approval rating is lower than François Mitterrand’s 51% rating in 1991.