Adversaries in World War II, fierce economic competitors in the 1980s and early 1990s, Americans and Japanese nonetheless share a deep mutual respect.

The animosity of the 1980s and 1990s, when U.S.-Japan relations were marked by a series of trade wars, has all but vanished. Just 8% of Americans cite that period of intense trade friction as the most important event in modern U.S.-Japan relations. The number of Americans calling Japanese trade practices unfair has fallen from 63% in 1989 to just 24% currently. More than half think that Japan’s trade policy toward the U.S. is fair.

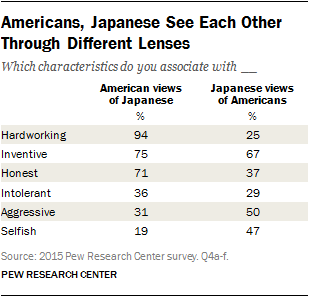

On a personal level, Americans associate positive personality traits with the Japanese, but do not associate negative stereotypes with people in Japan. Americans overwhelmingly see Japanese as hardworking, inventive and honest.

These are among the main findings of Pew Research Center nationwide phone surveys conducted in the United States among 1,000 adults from February 12 to February 15, 2015, and in Japan among 1,000 adults from January 30 to February 12, 2015. The surveys were conducted in association with Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA.

The Role of History in the U.S.-Japan Relationship

Since the 1940s, U.S.-Japan relations have been marked by military conflict, strategic partnership, “trade wars” and an unprecedented natural disaster. No single event in the recent relationship dominates public memory in either Japan or the U.S. And different incidents feature most prominently in American and Japanese consciousness.

For Americans, the most significant periods in the U.S.-Japan relationship bookend the modern era. Nearly a third (31%) cite World War II as the event that stands out when they think about relations between the United States and Japan over the past 75 years. The same proportion (31%) mentions the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan. About a quarter (23%) names the U.S.-Japan military alliance after WWII. And very few, just 8%, say the “trade wars” between the U.S. and Japan in the 1980s and early 1990s were the most important event.

For Japanese, the most important aspect of the relationship is the ongoing U.S.-Japan military alliance (36%). One-in-five cite the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami, possibly a reflection of the fact that 24,000 U.S. service members were involved in humanitarian relief and Americans donated more than $700 million in aid to disaster victims. Only 17% of Japanese say WWII is the most significant occurrence in modern bilateral ties. And 14% mention the period of trade friction.

As might be expected, it is Americans ages 65 and older (40%) who are most likely to cite WWII as most important when they think about the U.S.-Japan relationship. The least likely to mention the conflict are not young people but those born right after the war, people ages 50 to 64 (24%). Notably, there is no significant generation gap among Japanese in their memories of the war.

In Japan, men (42%) more than women (29%) are most likely to cite the strategic alliance as the most important event in recent U.S.-Japan relations. Similarly, people ages 18 to 29 (40%) name the military partnership more than those ages 65 and older (29%).

Even among the demographic groups in the U.S. who might be expected to harbor grievances about the bilateral trade disputes of the 1980s and early 1990s, that contentious period does not play a major role in their memories. Just 13% of those ages 50 to 64, who were in their prime working years when there was widespread concern about the rise of “Japan Inc.”, cite the U.S.-Japan trade wars as the most prominent event in the bilateral relationship. Similarly, during that period, Democrats were often more critical of Japanese trade policy than were Republicans. But only 10% of Democrats today point to the era of trade friction as the most important period in recent U.S.-Japan .

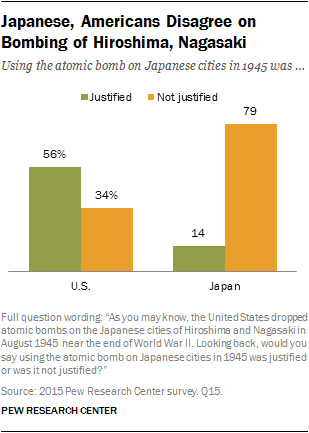

One event during WWII – the U.S. dropping atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 – has long divided Americans and Japanese. Americans, in surveys with similar wording, have consistently approved of this first and only use of nuclear weapons in war and have thought it was justified. The Japanese have not.

In 1945, a Gallup poll immediately after the bombing found that 85% of Americans approved of using the new atomic weapon on Japanese cities. In 1991, according to a Detroit Free Press survey conducted in both Japan and the U.S., 63% of Americans voiced the view that the atomic bomb attacks on Japan were a justified means of ending the war; only 29% thought the action was unjustified. At the same time, only 29% of Japanese said the atom bombing was justified, while 64% thought it was unwarranted.

Not surprisingly, there is a large generation gap among Americans in attitudes toward the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Seven-in-ten (70%) Americans 65 years of age and older say the use of atomic weapons was justified, but only 47% of 18- to 29-year-olds agree. There is a similar partisan divide: 74% of Republicans but only 52% of Democrats see the use of nuclear weapons at the end of WWII as warranted. Men (62%) more than women (50%), and whites (65%) more than non-whites (40%), including Hispanics, say dropping the atomic bombs was.

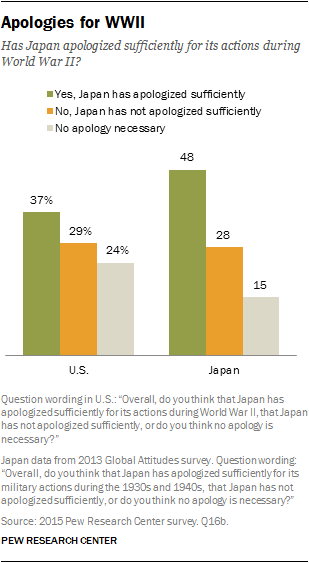

Despite this lingering disagreement over the justification for Hiroshima and Nagasaki, few Americans or Japanese believe Japan owes an apology for its actions during WWII.

A majority of Americans have moved past Japan’s actions during WWII (61%). More than a third (37%) says that Japan has apologized sufficiently for WWII and 24% say that no apology is now necessary. Just 29% voice the view that Japan has not apologized sufficiently for its actions during the war. Again, it is younger Americans (73%) who are most likely to put Japan’s role in WWII behind them, while older Americans (50%) are less convinced.

In a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, 48% of Japanese said they felt Japan had apologized sufficiently for its military actions during the 1930s and 1940s, while 28% felt their country had not apologized enough and 15% said there is nothing for which to apologize.

In another sign that the scars of WWII are healing, most Americans similarly see German responsibility for their actions during WWII as a settled issue. More than half say Germany has apologized sufficiently (33%) or that no apology is necessary (21%). Just 37% say Germans have not apologized enough. Again, younger Americans (64%) are more forgiving than older ones (43%).

The U.S.-Japan Relationship Today

Roughly two-thirds of Americans trust Japan either a great deal (26%) or a fair amount (42%). And three-quarters of Japanese share a similar degree of trust of the U.S., though their intensity is somewhat less (10% a great deal, 65% fair amount).

There is a gender gap in how both publics see each other. American men (76%) are more trusting of Japan than American women (59%), just as Japanese men (82%) voice greater trust in the U.S. than do Japanese women (68%).

Also in the U.S., whites (73%) are more likely than non-whites (56%), including Hispanics, to trust Japan. And people with at least some college education (75%) are more likely to have confidence in Japan than those with a high school education or less (56%). But there is no significant partisan difference among Americans in their trust of Japan.

Looking ahead, Americans generally support keeping the U.S. relationship with Japan about where it is. When asked whether they would prefer that the U.S. be closer to Japan, less close, or about as close to Japan as it has been in recent years, 38% say closer, 45% say about as close and only 13% would like to distance the U.S. from Japan. Again, there is a generation gap on the future of the relationship: 41% of younger Americans would like to see closer ties, but only 27% of older Americans agree. And there is partisan disagreement on the trajectory of the relationship with Japan: Democrats (41%) are more likely than Republicans (30%) to support closer ties.

The future of U.S.-Japan relations will, in large part, be a product of bilateral economic interaction. Japan is currently the fourth-largest trading partner of the U.S. and the second-largest foreign investor in the U.S. And Tokyo and Washington are in the process of negotiating deeper trade and investment bonds between the two nations as part of a broader effort with 10 other countries on both sides of the Pacific to create a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).

Nevertheless, Americans are somewhat divided when it comes to whether the U.S. should be putting more focus on Japan or on China when it comes to developing a strong economic relationship. Overall, a slightly larger share of Americans (43%) name China, which is not part of the TPP talks, as the more important economic partner than name Japan (36%). About one-in-eight Americans (12%) volunteer that it is important to have a strong economic relationship with both.

Americans’ views on the relative importance of economic ties with Japan and China divide along generational, racial and partisan lines. In particular, young Americans believe it is more important to have a strong economic relationship with China: About six-in-ten ages 18 to 29 hold this view. Less than half as many people 65 years of age and older agree. At the same time, twice as many older Americans as younger ones believe a strong economic relationship with Japan is a priority. Roughly half of non-white Americans prefer a strong relationship with China, while more than a third of whites make China a priority. And whites are more likely than non-whites to say it is more important to have a strong economic relationship with Japan. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to want better relations with Japan. Meanwhile, Democrats are more likely than the GOP to want stronger economic ties with China.

There are no such divisions in Japan about future economic relations with China and the U.S. Nearly eight-in-ten Japanese (78%) say it is more important to have strong economic connections with the U.S., while only 10% cite China. Young Japanese are more likely than their elders to back a deeper economic relationship with the U.S., but the preference for the U.S. among all age groups, and among all demographic subgroups in Japan, is still overwhelming.

In general, views about the relative importance of future economic ties may reflect public perceptions of the current and future strength of each other’s economies. A majority of Americans see Japan as a status quo economy, with 57% saying they believe Japan’s economic power will stay about the same relative to other countries. Just 28% view Japan as a rising economic power, while only 8% say Japan’s economy is declining. Views of young Americans diverge from those of their elders. They (42%) are more likely than those 65 and older (19%) to see Japan as a rising economic power. Yet young Americans are also much more supportive of closer economic ties with China.

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey provides insight into the Japanese preference for closer economic ties with the U.S. and Americans’ slight preference for a stronger economic relationship with China. In that poll, 59% of Japanese voiced the view that the U.S. was the world’s leading economic power; only 23% thought the top economy was China. At the same time, 41% of Americans said China was the world’s leading economy, but only 8% named Japan.

Americans’ economic tilt toward China comes despite grave doubts about China as a trading partner and a dramatic improvement in Americans’ views of their trade relationship with Japan. In 1989, amid serious trade tensions, just 22% of Americans held the view that Japan had a fair trade policy with the U.S., according to a Times Mirror survey. In 2015, 55% of Americans see Japan as a fair trader. At the same time only 37% of Americans view China as having a fair trade policy with the U.S. With regard to China, young Americans (52%) are much more likely than older Americans (23%) to call China a fair trader. And non-whites (52%) are much more likely than whites (29%) to say China trades fairly.

How the American and Japanese People See Each Other

Public views of other nationalities are often rooted in stereotypes. These perceived national characteristics may or may not be fair or accurate. But they capture a public perception that may help explain national attitudes on a range of other topics.

Americans overwhelmingly (94%) voice the view that the Japanese are hardworking. And three-quarters of Americans see the Japanese as inventive.

About seven-in-ten (71%) Americans also see the Japanese as honest. Those with at least some college education (75%) are more likely than Americans with only a high school education or less (64%) to characterize the Japanese in this manner.

Most Americans do not ascribe various negative stereotypes to the Japanese. Only 36% see the Japanese as intolerant, 31% voice the view that they are aggressive and just 19% associate the term “selfish” with Japanese people.

The Japanese tend to be more critical of Americans. Two-thirds of Japanese see Americans as inventive, with younger Japanese (76%), those ages 18 to 29, more likely to say this than their elders (53%), age 65 and older. But only 37% of Japanese associate honesty with Americans and only a quarter voice the view that Americans are hardworking.

At the same time, while just 29% of the Japanese public sees Americans as intolerant, 50% say Americans are aggressive and 47% view them as selfish.

Japan, China and the Region

U.S.-Japan relations are a relatively strong thread in a web of relations in the Asia-Pacific region. Americans and Japanese both trust each other more than they trust either China or South Korea. Meanwhile, both have high levels of confidence in Australia.

Just 30% of Americans trust China a great deal or a fair amount. Only 7% of Japanese trust Beijing, and then only a fair amount. Moreover, a quarter of Americans and half of Japanese do not trust China at all.

Young Americans, ages 18 to 29, are more likely to trust China (49%) than are older Americans (21%), age 65 and older. Democrats (39%) are more trusting of China than are Republicans (20%). There are no significant demographic differences in Japanese views of China.

Americans and Japanese also differ in their opinions of South Korea. Nearly half (49%) of Americans trust South Korea, but only 21% of Japanese agree. Yet, about a quarter (24%) of both Americans and Japanese do not trust South Korea at all. Notably, American men (57%) are much more likely than women (41%) to trust Seoul, as are whites (55%) more than non-whites (37%). Americans with at least some college education (58%) are more likely to trust South Korea than are people with only a high school education or less (36%). Despite the level of Japanese animosity toward South Korea, there are no significant demographic differences in Japanese views of South Korea.

Both Americans and Japanese overwhelmingly trust Australia, though Americans trust Australia far more intensely. In the U.S., eight-in-ten have a great deal (44%) or a fair amount (36%) of faith in Australia. Whites (89%) are more likely than non-whites (62%) to hold this positive opinion. In Japan, 17% trust Australia a great deal and 61% a fair amount.

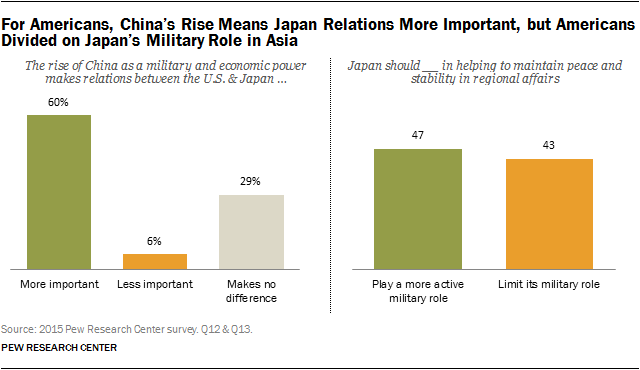

The rise of China as a military and economic power is one of the principal motivating factors driving the U.S. strategic and economic rebalancing toward Asia, and it plays an important role in U.S.-Japan relations.

Six-in-ten Americans voice the view that China’s rise makes relations between the U.S. and Japan more important. Just 6% say it makes ties less important and 29% believe it makes no difference. Men (67%) are more likely than women (54%), whites (67%) more than non-whites (48%), and Americans 65 years of age and older (65%) more likely than those ages 18 to 29 (51%) to hold the view that the Japan relationship is now more important because of China.

At the same time, the American public is divided over whether Japan should play a more active military role in helping to maintain peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific region: 47% would like to see Tokyo take a more active role and 43% would prefer that Japan limit its role. Americans who trust Japan are more likely to want to see Tokyo play a greater strategic role in the region. And Americans who do not trust China are also more likely to want to see Japan take on more of the military burden in Asia.

Among Japanese, there is little desire for their country to play a greater role in the region’s security. Just over two-thirds (68%) want Japan to limit its military activity. Only 23% want the country to play a more active role. Notably, it is Japanese men (30%) more than women (17%) who would like to see a more forward-leaning national strategic posture.

Americans’ and Japanese News Sources and Knowledge about Each Other

Americans’ views of Japan and of issues in Asia that affect U.S.-Japan relations are informed by the news media, as are Japanese views of the U.S.

Americans obtain their information about Japan largely from television (44%) or the internet (36%). Japanese are more dependent on television (65%) for their information about international issues concerning the U.S. and less likely to get it from the internet (15%). Newspapers play a bigger role for Japanese (16%) than they do for Americans (9%). And neither public relies much on radio (6% in the U.S. and 2% in Japan) or magazines (2% and 1%, respectively).

As might be expected, Americans 65 years of age and older are most likely to get their news of Japan from television (65%). Young Americans, ages 18 to 29, predominantly get their information about international issues concerning Japan from the internet (62%). Women (49%) are more likely than men (39%) to rely on television and men (41%) are more likely than women (32%) to go to the internet for news on Japan. Similarly, people with a high school education or less draw on television news (59%) for their information about Japan, while a plurality of people with at least some college education use the internet (44%).

In Japan, the generation gap among those who get their international news about the U.S. from the internet is even greater: 40% of young Japanese say they obtain information concerning America from the internet, but only 3% of older Japanese rely on the Web. A generation gap exists among television viewers as well, although it is much smaller: 67% of Japanese ages 65 and older get their information about the U.S. from television, compared with 55% of Japanese ages 18 to 29 who rely on TV. Japanese women (74%) are also much more likely to turn to television for news of the U.S. than are men (55%).

And Americans are much more aware of and have a more favorable view of Japanese commercial brands than they do of leading Japanese public figures.

More than eight-in-ten Americans have a favorable opinion of both electronics giant Sony (88%) and carmaker Toyota (85%). Roughly half (51%) hold a positive view of Pokémon, a brand of children’s video games, movies and television programs and toys from Nintendo.

At the same time, less than half (47%) voice a favorable opinion of Ichiro Suzuki, the most successful Japanese to play major league baseball in the U.S., perhaps in part because 32% volunteered that they had never heard of him.

Even less well-known are Japanese novelist Haruki Murakami, with 13% having favorable views and 69% having never heard of him; and former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi (12% favorable, 73% did not recognize his name).

Most striking of all, only 11% of Americans have a favorable view of current Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, but this can largely be attributed to the fact that 73% say they have never heard of him.

Americans’ awareness of major issues in Asia relating to Japan varies widely. More than eight-in-ten (81%) Americans have heard about North Korea’s nuclear program, including 39% who have heard a lot about it and another 42% who have heard a little. Among those who have heard a lot, it is men (45%) more than women (33%); older Americans (45%) more than young people (29%); and those with at least some college education (47%) more than those with only a high school education or less (27%).

Six-in-ten Americans have heard about China’s territorial disputes with its neighboring countries, but only 16% have heard a lot about them. And 39% of Americans have heard nothing at all.

Roughly four-in-ten (41%) Americans have heard about tensions between Japan and South Korea over the issue of “comfort women” during World War II. Just 10% have heard a lot about this controversy. Another 31% have heard a little, and 57% have heard nothing at all about it.

Americans’ general trust in Japan and appreciation for the Japanese people, coupled with at least some knowledge of the tensions in East Asia, may explain their greater interest in visiting Japan rather than other Asian nations.

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) express an interest in going on vacation to Japan, including 30% who are very interested. Roughly half (48%) say they are interested in visiting China, but only 20% are very interested. A similar proportion (48%) is interested in vacationing in Singapore. And only 30% voice an interest in visiting South Korea.