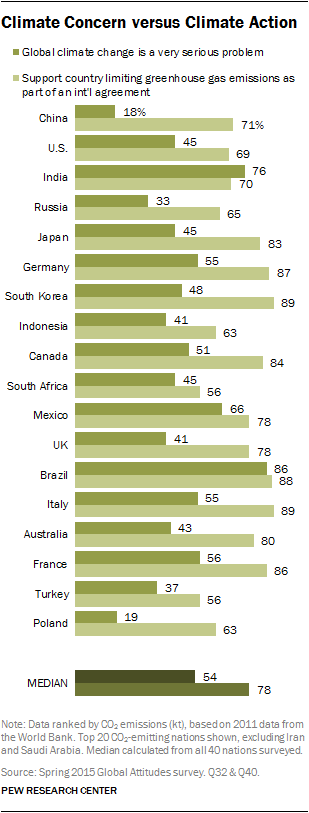

When it comes to climate change, publics around the world generally adopt the precautionary principle: Even when in doubt, act out of prudence. In 37 of 40 nations surveyed, willingness to curb emissions that may contribute to warming the planet exceeds intense concern about climate change.

Globally, a median of 54% consider climate change to be a very serious problem (a median of 85% say it is at least somewhat serious). But a much higher median (78%) support their country signing an international agreement limiting greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of coal, natural gas and petroleum.

Public willingness to support limitations on emissions exceeds the intensity of people’s climate concern in a number of other major carbon-emitting countries. This action-versus-concern gap is 38 percentage points in Japan, 32 points in Russia and 24 points in the U.S.

The differences between a relatively low perception of the climate challenge and public willingness to do something about it are even greater in other nations: in Israel (56 points) and Ukraine (48 points), countries which are not among the top 20 CO2 emitters, and in Poland (44 points) and South Korea (41 points), which are.

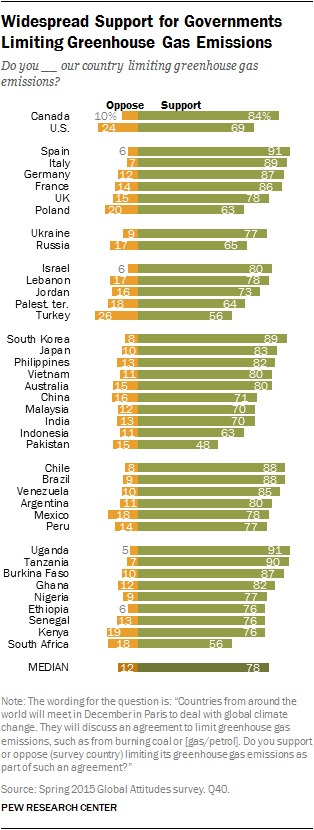

Regionally, the greatest enthusiasm for limiting emissions is in Europe (a median of 87%). Support is also quite strong in Latin America (median of 83%). The lowest backing, while still quite high, is in the Middle East (73%).

In a number of nations, publics express quite strong support for efforts to limit greenhouse emissions. Nine-in-ten or more Spaniards (91%), Ugandans (91%) and Tanzanians (90%) want their countries to curtail such pollution. They are joined by nearly as many Italians (89%), South Koreans (89%), Chileans (89%) and Brazilians (88%). This public support for taking action is particularly noteworthy because South Korea is among the top 10 nations responsible for annual CO2 emissions. And Brazil ranks No. 15 on the list.

The lowest backing for action to reduce emissions is in Pakistan (48%), Turkey (56%) and South Africa (56%). About a third (34%) of Pakistanis voice no view on the topic, as do 20% of South Africans and 16% of Turks, suggesting that a policy response to global warming is not high in the public consciousness.

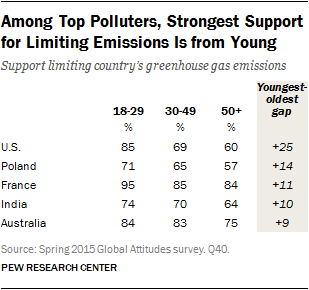

Among some other large economies – Australia, France, India and Poland – there are age differences in views on curbing emissions. There is a substantial generation gap in Poland, where younger Poles (71%) are more likely to back government curbs on global warming pollutants than are older Poles (57%). French ages 18 to 29 are almost unanimous (95%) in favoring the limitation of emissions. French ages 50 and older are slightly less enthusiastic (84%). Young Indians (74%) are more likely to favor curtailing the burning of petroleum and natural gas than are their elders (64%). And younger Australians (84%) are more supportive of their government signing an international climate accord in Paris than are older Australians (75%).

Calls for Rich Countries to Do More

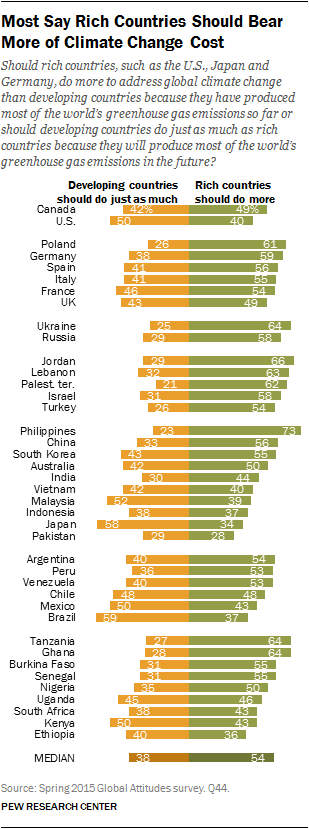

While publics in both rich and poor nations are generally supportive of their own governments taking action to curb greenhouse gas emissions, in principle many people believe that wealthy societies, not poor economies, should take on more of the responsibility for addressing climate change.

There are notable regional differences in views of who should take the lead in dealing with climate change. A median of 62% in the Middle East hold the view that wealthier nations bear the responsibility. And a median of 56% in Europe agree. But just 42% in Asia see the responsibility primarily resting with rich countries.

Not surprisingly, some of the greatest support for wealthier societies doing more is found in relatively poor economies that are not major sources of emissions. Publics in the Philippines (73%), Ghana (64%) and Tanzania (64%) say rich countries should do more.

Among the major polluters, 58% of the Russians say that any effort to combat climate change is principally the responsibility of the wealthier nations, as do 56% of the Chinese. (Whether these publics actually consider themselves rich or developing is unknown. This sentiment could represent either an assumption or rejection of responsibility.)

There is no such uncertainty about the sentiment of American and Japanese publics, both of which are indisputably wealthy by global standards. The U.S. economy is the second-highest contributor of annual CO2 emissions. But only four-in-ten Americans say rich nations should do more to address climate change than developing countries, while half of U.S. respondents say developing countries should do just as much. Despite partisan differences over many climate-related issues, more than half (54%) of both Democrats and Republicans believe that the burden of adjustment should be equally shared by both rich and poor nations.

Japan is fifth on the global list of annual CO2 emitters. And just 34% of Japanese believe rich countries should do more about climate change, while 58% say developing countries should do just as much as wealthy nations.

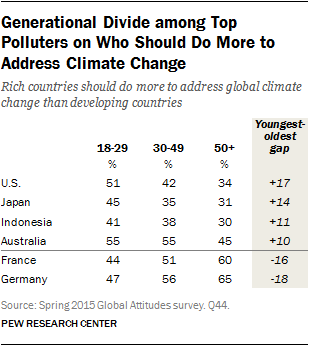

There is a generational divide in major emitting countries over who should bear the greatest burden in curtailing greenhouse gases. Young Americans, Japanese, Indonesians and Australians (those ages 18 to 29) are significantly more likely than their elders (ages 50 and older) to assert that rich countries should do more than developing nations to address climate change. This might be expected, since the younger generation may see itself as most likely to have to live with the consequences of global warming. But just the opposite generation gap exists in Germany and France. Older Germans and French, not young people, are the most supportive of rich countries taking the greatest responsibility in dealing with global warming.

Lifestyle Changes Seen as Necessary

Dealing with climate change may require a combination of technological innovation and changes in people’s lifestyles. And publics around the world believe that such lifestyle changes will be more important than technological change in combatting global warming.

By a ratio of three-to-one, those surveyed believe that people will have to make major changes in the way they live to reduce the effects of climate change rather than simply relying on technology to solve the problem. Notably, individuals who think they will be personally affected by climate change are more likely than others to believe in the necessity of major personal changes. Such lifestyle alterations would differ in both scope and scale from society to society, of course.

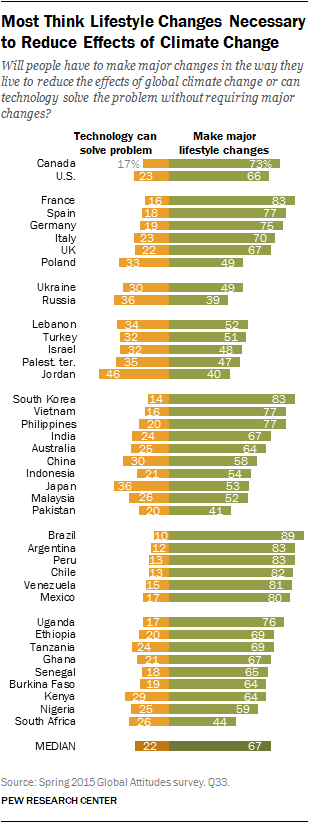

A global median of 67% say they expect that reducing the effects of climate change will require people to make major changes. A median of just 22% believe that technology will solve the problem.

At the national level, the Brazilians (89%), French (83%) and South Koreans (83%) are among those most likely to endorse modifications in the way they live to better cope with global warming. The least likely to believe that personal changes are needed are the Russians (39%) and the Jordanians (40%).

Among countries that bear the greatest responsibility for CO2 emissions, 58% of Chinese voice support for lifestyle changes to cope with climate change, as do roughly two-thirds of Americans (66%). Despite their long-standing faith in technology, only about a quarter of Americans (23%) think technological innovation will obviate the necessity for lifestyle changes. And more than half of Japanese (53%) favor personal change, while 36% look to technology to solve the problem rather than major changes to how people live.

In Jordan, opinion on this issue is split about evenly. While 46% of Jordanians believe technology without lifestyle changes will solve the climate problem, 40% believe it will take lifestyle changes. The belief that technology will come to the rescue is strongest throughout the Middle East (a median of 34%).

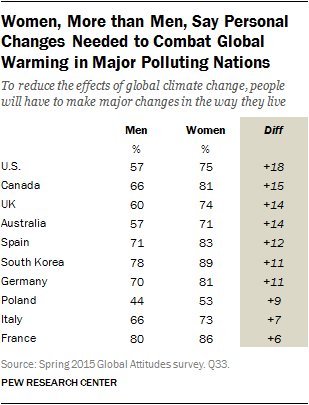

In a number of the advanced economies that are responsible for much of annual CO2 emissions, it is women, more than men, who believe major changes in the way they live will be necessary to reduce the effects of global climate change. This gender difference on the contribution required from lifestyle changes is particularly large in the U.S. (18 percentage points), Canada (15 points), the UK (14 points) and Australia (14 points).

Contrary to what might be expected, there are not major generational differences on whether lifestyle changes are needed to cope with global warming or whether technological innovation can be counted on to solve the problem.

But in a number of advanced economies, there are partisan differences over the need for people to adjust the way they live. In the U.S., 79% of Democrats but only 55% of Republicans see a need for lifestyle changes. There is a three-way partisan split in Canada, with 86% of NDP adherents voicing the view that people will have to change and 75% of Liberals holding that opinion, but only 57% of Conservatives agreeing. And in the UK there is an 18 point difference on such personal responsibility between Labour supporters (74%) and Conservatives (56%).

The Energy Mix

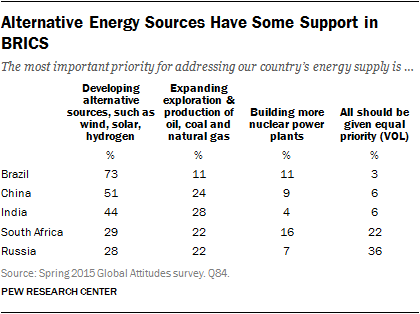

Emerging economies – especially the BRICS: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – are rapidly contributing to annual global CO2 emissions as their industrialization and growing middle class lead to increased energy needs, which are often fulfilled by burning more fossil fuels. Efforts to balance rising energy demand with public concern over climate change have led to debates within these societies over their future energy mix. In a number of these major emerging economies, publics give their highest priority to developing alternative energy sources such as wind, solar and hydrogen technologies.

In Brazil, the public overwhelmingly favors giving alternative sources (73%) priority in addressing the country’s energy supply needs. Just 11% back expanding exploration and production of oil, coal and natural gas, and another 11% support building more nuclear power plants.

Roughly half the Chinese (51%) also prefer alternative energy as a way to fulfill future energy demand. About a quarter (24%) prefer fossil fuels.

More than four-in-ten Indians (44%) would like to see their country rely more on wind, solar and hydrogen in the future, while 28% are committed to oil, coal and natural gas. Just 4% of Indians prefer nuclear power, despite there being 21 such generating plants now in operation, six facilities under construction and 22 planned. And roughly one-in-six Indians voice no opinion on their country’s energy mix.