In the wake of prolonged economic stagnation, a massive influx of refugees, terrorist attacks and a strategic challenge posed by Russia, many Europeans are weary – and perhaps wary – of foreign entanglements, according to a new Pew Research Center survey. Views of their respective countries’ place in the world vary widely, but few see the past decade as a time of growing national importance. And across the continent publics are divided: Many favor looking inward to focus on domestic issues, while others question whether commitments to allies should take precedence over national interests.

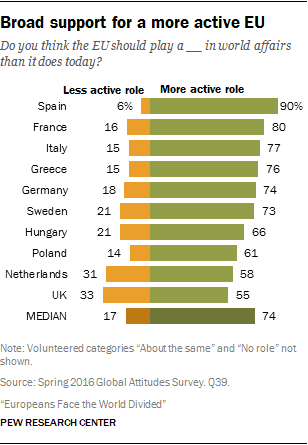

Yet Europeans have not completely turned their backs on the world. Although deeply critical of how the European Union has handled the refugee crisis, the economy and Russia, they acknowledge the Brussels-based institution’s rising international prominence and want it to take a more active role in world affairs. Involvement in the international economy is also widely supported and Europeans generally feel an obligation to help developing nations.

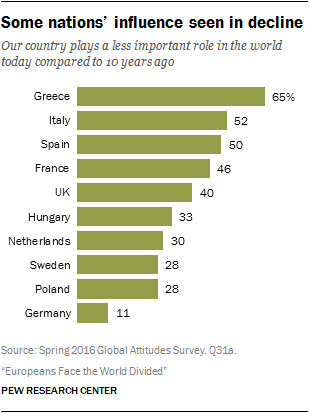

Waning international confidence afflicts a number of European societies. Only the Germans and the Poles believe their countries play a more important role as a world leader today compared to a decade ago. And pluralities of Greeks, Italians, Spanish and French say their countries are less prominent today, not more.

These are among the key findings from a new survey by Pew Research Center, conducted in 10 EU nations and the United States among 11,494 respondents from April 4 to May 12, 2016. The EU portion of this survey covers countries that account for 80% of the member nations’ combined population and 82% of the EU-28 gross domestic product.

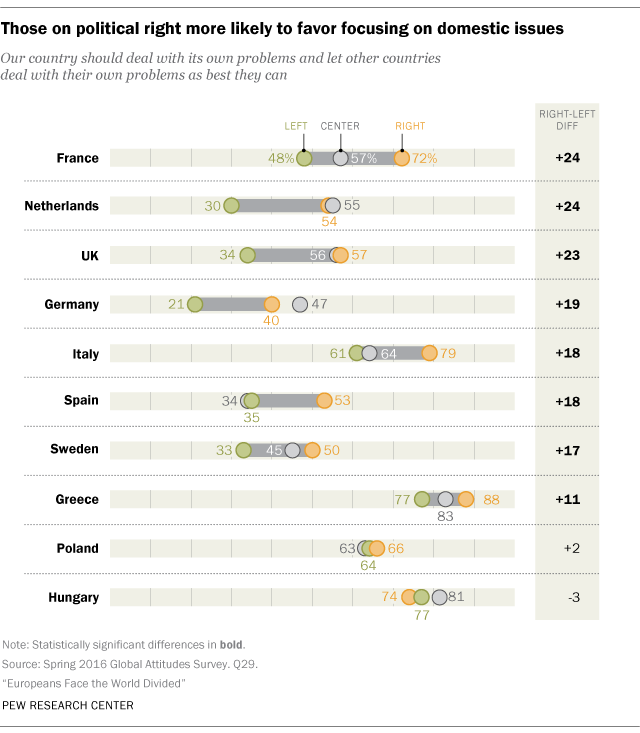

Views of global engagement divide along ideological and party lines in many of the surveyed publics. In most countries people on the right of the political spectrum are much more likely than those on the left to say their nation should focus on domestic problems, not help others. And in six of the 10 countries polled people on the right are more likely than those on the left to believe that their government should pursue national interests in foreign policy even if allies strongly disagree.

Similarly, 85% of UKIP supporters, but just 39% of Labour adherents believe the British government should follow national interests in international affairs even if UK allies strongly disagree. Fully 68% of National Front supporters in France say Paris should pursue national interests in foreign policy irrespective of the opinion of France’s allies. Only 46% of ruling Socialist Party adherents agree.

“France First” or “Britain First” sentiment does not mean Europeans are unmindful of international challenges. Overwhelming majorities voice the view that the Islamic militant group in Iraq and Syria known as ISIS poses a major threat to their countries. Yet there is little support for boosting national defense spending (a median of just 33% across the 10 EU countries are in favor) and a reluctance (a median of only 41%) to use overwhelming military force to defeat terrorism.

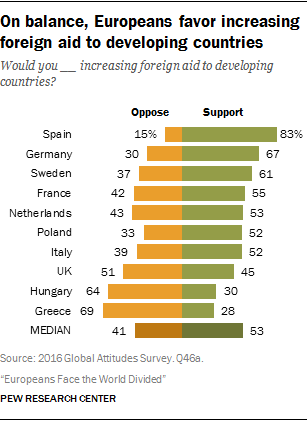

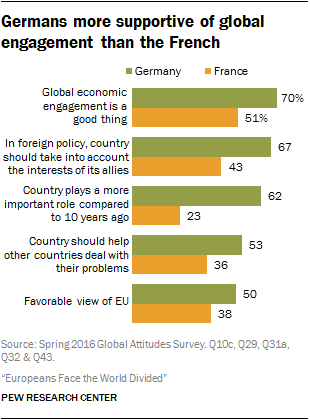

Nor are all Europeans increasingly isolationist in any traditional sense of the word. The Germans and the Swedes in particular are outward looking and committed to multilateralism to a degree not found in France, Greece, Hungary, Italy or Poland. Nation-first sentiment is largely unchanged in the countries where this question on whether to deal with a country’s own problems or help other countries deal with their problems was also asked six years ago. Europeans have a sense of obligation to help those in developing nations: In seven of 10 countries half or more of the public supports increasing foreign aid. Similarly, in seven of 10 nations half or more voice the view that global economic engagement is a good thing for their nation.

Europeans agree on top threats

Among eight potential threats asked about in the survey, Europeans clearly see ISIS as the top danger to their countries. Roughly seven-in-ten or more in every country surveyed say that ISIS is a major threat, with the greatest concern coming from the Spanish (93%) and French (91%). (Deadly terrorist attacks hit the major European capitals of Paris and Brussels just months before this survey was conducted.) Europeans are also troubled by global climate change. More than half in all 10 countries polled say that climate change is a major menace, with 89% of Spanish and 84% of Greeks saying this. Many Europeans also say global economic instability and cyberattacks are major problems.

On the issue of refugees from countries such as Iraq and Syria, there are sharp divides. In Poland, Hungary, Greece and Italy people are much more concerned about the refugee crisis as a threat compared with publics in the Netherlands, Germany and Sweden. But there is also a divide within nations by political ideology. In eight European countries, those on the political right are more likely than those on the left to express concern about the refugee problem. This is most evident in France, where 61% on the right say the large number of refugees leaving the Middle East is a major threat to France, compared with only 29% who say this on the left.

Mixed views on promoting human rights, some support for foreign aid

On the role of human rights in making foreign policy, opinions vary considerably across the 10 nations surveyed. More than half of those polled in Spain, Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands say human rights should be a top foreign policy priority. In contrast, Hungarians, Greeks, Poles and Italians tend to believe that while human rights are important, many other foreign policy goals matter more. Public opinion is roughly divided on this issue in the UK and France. In most nations, people on the political left put a greater emphasis on the importance of human rights than people on the political right.

Europeans tend to favor increasing foreign aid to developing countries. Half or more express this view in seven nations. The exceptions are Greece (69% oppose), Hungary (65%) and the UK (51%). And support for increasing foreign aid is higher on the ideological left in five of the 10 nations.

There is even greater support for increasing domestic companies’ investment in developing nations (a median of 76% across the 10 nations back this idea) and importing more goods from developing countries (a median of 64%).

The German-French divide

More than a half century after the signing of the Élysée Treaty that called for a common stance between France and what was then West Germany on a range of issues, a profound gulf exists in how the German and French people see their respective places in the world. Germans are confident about their nation’s role on the international stage. They are outward looking and committed to multilateralism and engagement in the world economy. The French are downbeat about France’s stature, inward looking and wary of globalization and cooperation with their allies.

UK ambivalence

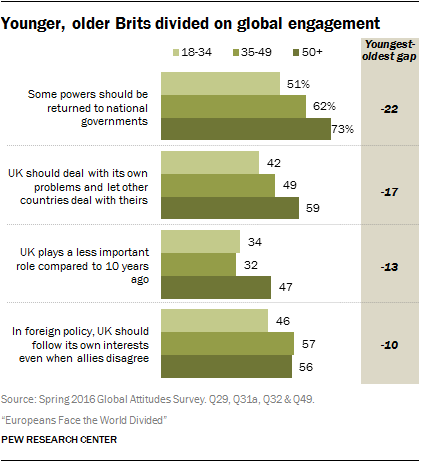

The June 23 British vote on whether to remain in or leave the European Union, known as Brexit, is just the latest example of long-running British ambivalence about membership in the Brussels-based institution. Many British voice a wariness of global engagement that belies the UK’s history as a major player on the world stage.

Roughly half the British (52%) believe that the UK should deal with its own problems and let other nations deal with their own problems as best they can. And a similar proportion (54%) says the UK should follow its own national interests even when its allies strongly disagree. Regardless of whether Brexit is approved, 65% of the British public believes that some EU powers should be returned to the British government. Some of this global circumspection may reflect the fact that four-in-ten British think the UK plays a less important part in the world today than it did a decade ago, compared with two-in-ten who believe it plays a more important role.

There is a prominent generational divide among the British on many of these issues. Nearly six-in-ten (59%) of older British – ages 50 and above – believe the UK should focus on dealing with its own problems. Just 42% of younger British (ages 18 to 34) agree. And 56% of older British believe that the UK should follow its own national interests even when its allies disagree, while only 46% of younger British concur. More than seven-in-ten of older British (73%) want to bring some EU powers back to London, but only 51% of younger British express that desire. And 47% of those ages 50 and older think the UK plays less of a role in world affairs today, while just 34% of those ages 18 to 34 hold this downbeat view.

Both sides of the Atlantic turn inward

In how they see their country’s place in the world, people on both sides of the Atlantic tend to be inward looking, and many question their country’s importance in world affairs. Americans, however, are much more pessimistic about the benefits of global economic engagement. (For an in-depth look at how Americans view their place in the world, see this recent Pew Research Center survey.)

A median of 56% across the 10 EU nations surveyed and 57% of Americans believe their country should deal with its own problems and let other nations deal with theirs as best they can. But while this nation-first sentiment has seen little change in recent years in Europe, it has grown by 11 percentage points since 2010 in the U.S. The Greeks, Hungarians, Italians, Poles and French are all more inward looking than the Americans. The Swedes, Germans and Spanish are far less so.

In the U.S., 46% voice the view that their country is less important today than it was a decade ago. Among Europeans, a median of 37% share this view. But European opinions vary widely: While 62% of Germans see their country as more important, only 19% of Italians and 17% of Greeks are more confident in their homeland.

The greatest difference in views between Americans and Europeans involves the economy: 49% of Americans say global economic engagement is bad for their country, but 32% of Europeans view such involvement negatively. Only the Greeks see international economic engagement as a worse thing than Americans do.

CORRECTION (April 2017): The topline accompanying this report has been updated to reflect a revised weight for the Netherlands data, which corrects the percentages for two regions. The changes due to this adjustment are very minor and do not materially change the analysis of the report. For a summary of changes, see here. For updated demographic figures for the Netherlands, please contact info@pewresearch.org.