Migrants leaving their homes for a new country often carry a smartphone to communicate with family that may have stayed behind and to help search for border crossings, find useful information about their journey or search for details about their destination. The digital footprints left by online searches can provide insight into the movement of migrants as they transit between countries and settle in new locations, according to a new Pew Research Center analysis of refugee flows between the Middle East and Europe.1

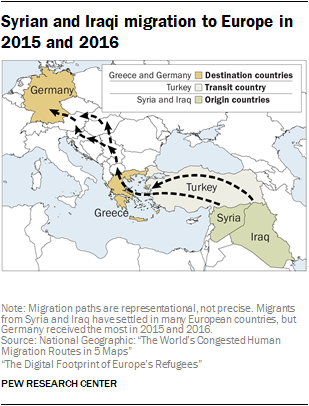

Refugees from just two Middle Eastern countries — Syria and Iraq — made up a combined 38% of the record 1.3 million people who arrived and applied for asylum in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland in 2015 and a combined 37% of the 1.2 million first-time asylum applications in 2016. Most Syrian and Iraqi refugees during this period crossed from Turkey to Greece by sea, before continuing on to their final destinations in Europe.

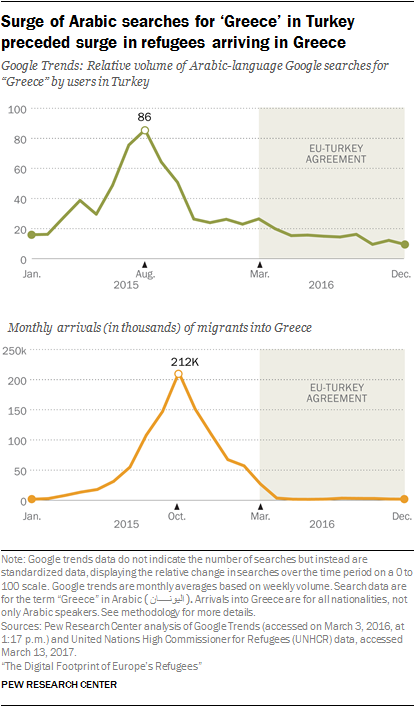

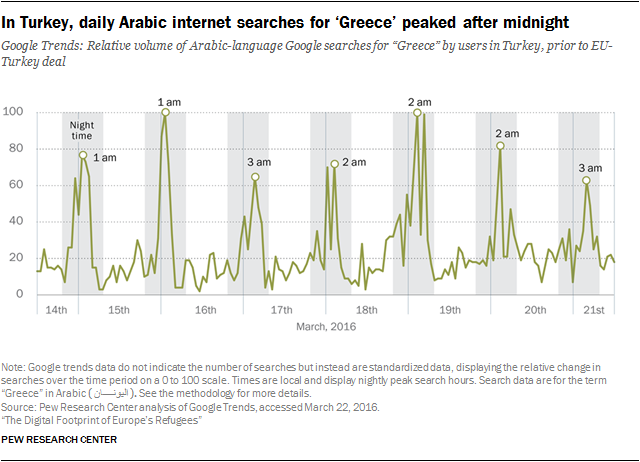

Since many refugees from Syria and Iraq speak Arabic as their native, if not only, language, it is possible to identify key moments in their migration by examining trends in internet searches conducted in Turkey using Arabic, as opposed to the dominant Turkic languages in that country. For example, Turkey-based searches for the word “Greece” in Arabic closely mirror 2015 and 2016 fluctuations in the number of refugees crossing the Aegean Sea to Greece. The searches also provide a window into how migrants planned to move across borders — for example, the search term “Greece” was often combined with “smuggler.” In addition, an hourly analysis of searches in Turkey shows spikes in the search term “Greece” during early morning hours, a typical time for migrants making their way across the Mediterranean.

Comparing online searches with migration data

This report’s analysis compares data from internet searches with government and international agency refugee arrival and asylum application data in Europe from 2015 and 2016. Internet searches were captured from Google Trends, a publicly-available analytical tool that standardizes search volume by language and location over time. The analysis examines searches in Arabic, done in Turkey and Germany, for selected words such as “Greece” or “German” that can be linked to migration patterns. For a complete list of search terms employed, see the methodology. Google releases hourly, daily and weekly search data.

Google does not release the actual number of searches conducted but provides a metric capturing the relative change in searches over a specified time period. The metric ranges from 0 to 100 and indicates low- or high-volume search activity for the time period. Predicting or deciphering human behavior from the analysis of internet searches has limitations and remains experimental. But, internet search data does offer a potentially promising way to explore migration flows crossing international borders.

Migration data cited in this report come from two sources. The first is the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which provides data on new arrivals into Greece on a monthly basis. The second is first-time asylum applications from Eurostat, Europe’s statistical agency. Since both Syrian and Iraqi asylum seekers have had fairly high acceptance rates in Europe, it is likely that most Syrian and Iraqi migrants entering during 2015 and 2016 were counted by UNHCR and applied for asylum with European authorities.

The unique circumstances of this Syrian and Iraqi migration — the technology used by refugees, the large and sudden movement of refugees and language groups in transit and destination countries — presents a unique opportunity to integrate the analysis of online searches and migration data. The conditions that permit this type of analysis may not apply in other circumstances where migrants are moving between countries.

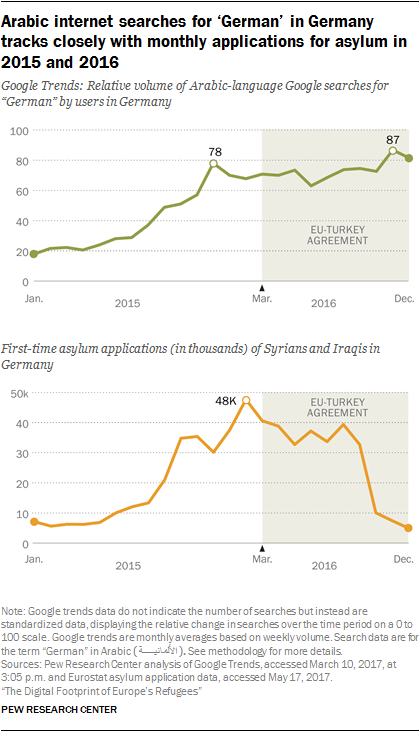

Once in Europe, nearly six-in-ten (57%) Syrian and Iraqi refugees in 2015 and 2016 applied for asylum in Germany. Just as with Turkey, Germany’s population is largely non-Arabic speaking.2 The trend in the monthly number of asylum applications in Germany closely mirrors online Arabic searches from Germany. For example, in 2015 and 2016, Arabic-language searches for the word “German” — a likely search term for arrivals navigating their new environment — follow similar changes in the number of monthly asylum applications of Syrian and Iraqi migrants in Germany, according to the Center’s analysis.

From Turkey to Greece: Internet searches and migrant flows into Europe

During 2015 and 2016, hundreds of thousands of people traveled by boat from the Turkish coast to the shores of Greece, hoping to gain refugee status in Europe. Many of these asylum seekers used smartphones during their journey, which provided access to information and maps, as well as travel advice via social media.3

At the time, migrants transiting Turkey largely were from Syria and Iraq, both predominantly Arabic-speaking countries. It is likely that in 2015 and 2016 these same migrants were responsible for most Arabic internet searches in Turkey — a country where Turkish is the predominant language.

Arabic-language Google searches in Turkey for the word “Greece” peaked in August 2015; two months later, the volume of migrants arriving in Greece also peaked. Plausibly, this is more than a coincidence. The two-month gap between the peak volume of searches and the peak number of new asylum applicant arrivals in Greece could be explained by the time it takes migrants to arrange for passage and to be processed upon arrival.4

The relationship between Arabic searches for the word “Greece” in Turkey and arrivals into Greece were not as highly linked following the EU-Turkey deal, a plan to stem the flow of migrants from Turkey into Greece implemented by EU and Turkish officials on March 20, 2016. Following the deal, refugee arrivals averaged between 2,000 and 3,000 each month. Nonetheless, online searches for “Greece” in Arabic continued at nearly pre-surge levels. In other words, would-be migrants likely continued to search for migration help, but many did not actually migrate, possibly because of the new travel restrictions.

Analysis by the hour, rather than month, reveals that the search term “Greece” was most frequently searched between 1 a.m. and 3 a.m., local time, particularly before the EU-Turkey agreement was implemented.5 Separate reporting finds that many migrants made the journey across the Eastern Mediterranean in the middle of the night.6

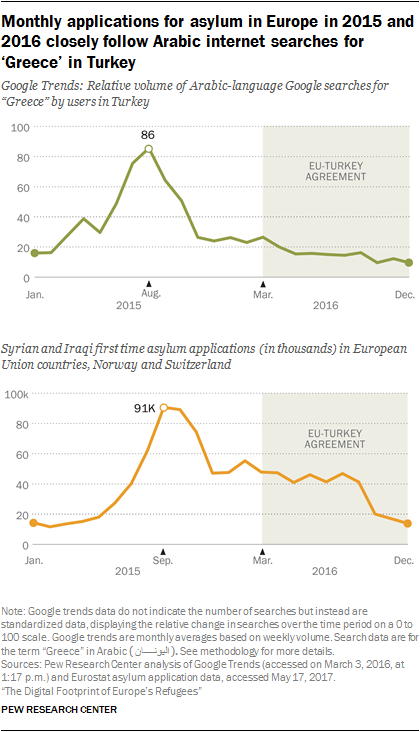

Online Arabic searches in Turkey for the term “Greece” also track with the number of people from Syria and Iraq applying for asylum in EU countries, plus Norway and Switzerland. For example, the surge in online searches was followed by a spike in asylum applications from these countries one to two months later. Again, this is likely more than coincidence, as for some Syrian and Iraqi migrants the journey through Greece and on to other countries further north (mostly to Germany, Hungary or Sweden) could take weeks.

Following the EU-Turkey agreement, both online searches and number of asylum applications sharply fell, and continued to steadily decline throughout most of 2016. However, a closer examination finds that the month to month relationship between online searches for “Greece” and subsequent asylum applications is not as strong following the EU-Turkey deal.

Into Germany: Internet searches also show refugee arrivals

The digital footprints of migrants are not just limited to their initial journey. Once within Europe, refugees are expected to apply for asylum in the first European country they enter, and wait in that country for their applications to be processed.7 However, some refugees move between European countries, applying for refugee status in more than one along the way.8

Online, Arabic-language searches for the word “German” in the country of Germany provide another indicator of the migration flow of Syrians and Iraqis into Europe. (The search term “German” is a likely word new migrants would search when trying to translate text from Arabic to German online or to learn new German words). Online searches for “German” track with the number of new asylum applications of Syrian and Iraqi migrants in Germany for most of 2015 and 2016.

Migration from Turkey to Greece dropped off considerably following the EU-Turkey agreement in March 2016. But it appears that even though Syrian and Iraqi refugees may have largely stopped traveling to Europe after the agreement, Syrians and Iraqis already in Europe, such as those in Hungary, continued to find ways to enter Germany and other European countries and apply for asylum there. And several months could have passed before applications were registered within Germany, even though the refugees had arrived much earlier.

Google searches in Arabic for “German” remained strong even though asylum applications in Germany dropped off significantly by October 2016. As indicated by a growing number of new arrivals enrolled in German integration courses, Syrians and Iraqis may have continued to search for the term “German” even though the number of asylum applications has fallen.

Terminology

“Refugees” and “asylum seekers” are people who have crossed international borders to receive protection from persecution, war or violence. These populations remain refugees or asylum seekers until they are permanently resettled outside of their birth countries or return to their homelands. Even though “refugee” can denote a certain legal status in Europe, the terms “refugee,” “asylum seeker” and “migrant” are used interchangeably in this report to describe this population.

“Europe” is used in this report as shorthand for the 28 nation-states that form the European Union (EU) as well as Norway and Switzerland, for a total of 30 countries. At the time of this report’s publication, the UK was still part of the European Union, although the country voted on June 23, 2016 to leave the EU.

“Internet searches” and “online searches” are used interchangeably and refer to searches users enter into search engines. The data used for this report relies on searches made on Google (see Google Trends below).

“Google Trends” is an analytical tool that reports the standardized volume of internet search terms on a scale of 0 to 100 entered into google.com during a specified period of time, based on location and language. This project uses data from the publicly available Google Trends website. See methodology for more information.