In Western Europe, populist parties and movements have disrupted the region’s political landscape by making significant gains at the ballot box – from the Brexit referendum to national elections in Italy. The anti-establishment sentiments helping to fuel the populist wave can be found on the left, center and right of the ideological spectrum, as a Pew Research Center survey highlights. People who hold these populist views are more frustrated with traditional institutions, such as their national parliament and the European Union, than are their mainstream counterparts. They are also more concerned about the economy and anxious about the impact of immigrants on their society.

This dissatisfaction may in part be why they are more favorable toward populist parties; still, regardless of populist sentiments, people tend to favor parties that reflect their own ideological orientation. With regard to policy, too, ideology continues to matter. Left-right differences carry more weight than populist sympathies when it comes to how people view the government’s involvement in the economy, as well as the rights of gays and lesbians and women’s role in society.

These are among the findings of an in-depth Pew Research Center public opinion study that maps the political space in eight Western European countries – Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom – based on a survey of 16,114 adults conducted from Oct. 30 to Dec. 20, 2017. Together, these eight European Union (EU) member states account for roughly 70% of the EU population and 75% of the EU economy.1 The study’s purpose is to evaluate how the intersection of ideology and populist views within and across these publics shapes attitudes about policies, institutions, political parties and values.

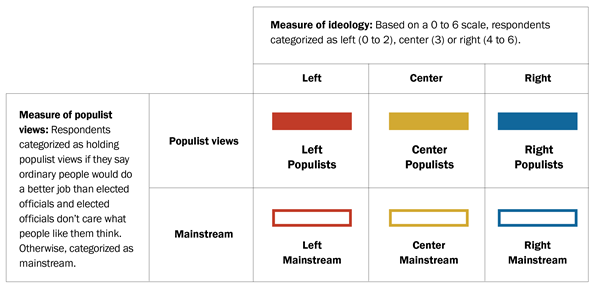

In this report, survey respondents are categorized into groups based on their self-placement along the left-center-right ideological spectrum and on whether they express support for populist views. The measure of ideology is general and not specific to either economic or social values. The measure of populist views primarily focuses on anti-establishment attitudes – whether respondents believe that ordinary people would do a better job than elected officials at solving the country’s problems, and whether most elected officials care what people like them think. Anti-establishment attitudes constitute a core component of many definitions of populism. In this analysis, the combination of ideology and anti-establishment attitudes leads to the identification of six political groups: Left Populists, Left Mainstream, Center Populists, Center Mainstream, Right Populists and Right Mainstream. (For more on how these groups are defined, please see the explanatory box and Appendix A.)

To measure left-right ideology, the survey uses a traditional question that asks respondents to place themselves on a left-right ideological scale, where zero represents the far left, and six represents the far right. People who answer 0, 1 or 2 on this scale are categorized on the left; people who answer 3 are categorized in the center; and people who answer 4, 5 or 6 are categorized on the right. Those who do not place themselves on the ideological scale are referred to as Unaligned. This measure of ideology is a general measure of ideology and is not specifically defined based on economic versus social values.

To measure populist views, the survey focused on capturing two core components of populism: that government should reflect the will of “the people,” and that “the people” and “elites” are opposing, antagonistic groups. The measure is based on combining respondents’ answers to two questions: 1) Ordinary people would do a better job/do no better solving the country’s problems than elected officials and 2) Most elected officials care/don’t care what people like me think. Those who answer that ordinary people would do a better job solving the country’s problems than elected officials and that elected officials don’t care about people like them are categorized as holding populist views. Everyone else is categorized as mainstream. For ease of reference throughout the report, we call these groups populist and mainstream. But it is important to keep in mind that these are broad measures that focus on anti-establishment views as a key aspect of populist support. The populist group may include some people who do not consider themselves populist or populist supporters, while the mainstream group may include some people who do. Still, as the analysis shows, the two groups reveal consistent, distinct attitudinal patterns across a range of issues.

The measures of left-right ideology and of populist views are combined to create six key groups that compose the primary analytical approach in this report. The groups are referred to as: Left Populists, Left Mainstream, Center Populists, Center Mainstream, Right Populists and Right Mainstream.

For more information on these measures, see Appendix A.

People who hold populist views are more unhappy with institutions, economy and immigration

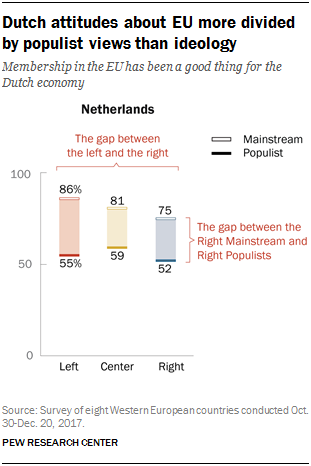

Across the ideological spectrum, people with populist views share a deep distrust of traditional institutions. This dissatisfaction affects not just attitudes about the national parliament but a range of institutions across society, including the news media and banks, as well as the European Union (EU). In fact, when it comes to opinions of the EU, populist views are often a more significant dividing line than ideology. For example, in the Netherlands, roughly six-in-ten or fewer among the left, center and right populist groups say that membership in the Brussels-based organization has been good for their country’s economy, compared with three-quarters or more among those in the mainstream on the left, center and right. People with populist sympathies also express higher support for returning powers from the EU to their national government than those in the mainstream. (For more on Western European views of the news media, see “In Western Europe, Public Attitudes Toward News Media More Divided by Populist Views Than Left-Right Ideology”.)

Journalists and scholars have fiercely debated whether economic struggles underlie publics’ support for populist movements. By analyzing populist views across the ideological spectrum, this study finds that people who are critical of the establishment are somewhat more likely than those in the mainstream to have faced economic hardship, such as unemployment. Perhaps in part because of this experience, Left, Center and Right Populists are much more dissatisfied with the national economy and, in half the countries surveyed, more likely than their mainstream ideological counterparts to support the government providing economic assistance to the public.

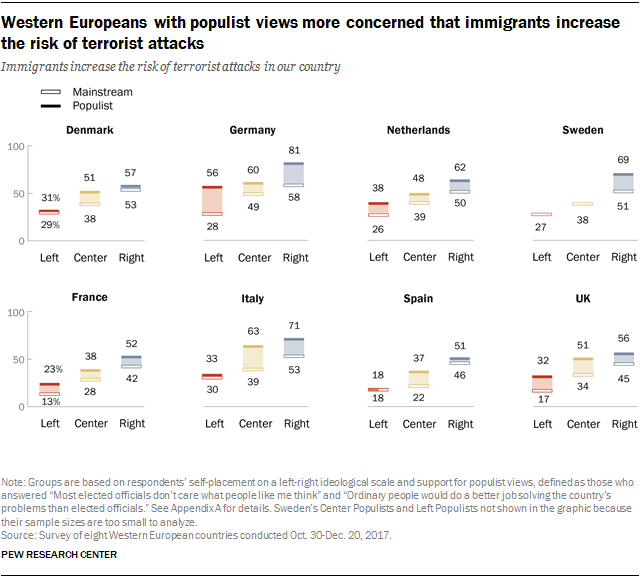

Additionally, anti-establishment sentiments and attitudes about immigration are linked, the study finds. Overall, left-right ideology is the most prominent divide in public attitudes about immigrants. Still, across the left-right spectrum, respondents with populist views are consistently more negative toward immigrants than those in the mainstream who share their ideological position. For example, in the Netherlands, both Left Populist and Left Mainstream respondents are less likely than their counterparts on the right to say immigrants increase the risk of terrorism. At the same time, the Left Populist group (38%) still expresses higher levels of concern than the Left Mainstream (26%). Similarly, the Center and Right Populist groups in the Netherlands generally hold more negative attitudes about immigrants than the Center and Right Mainstream groups, respectively. Across a number of questions about immigrants, Right Populists tend to be the most negative group.

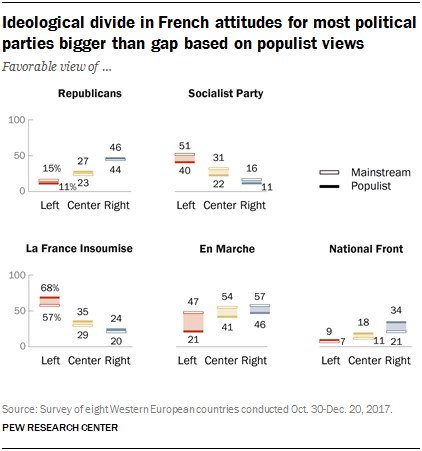

Given this pattern of attitudes, it is perhaps unsurprising that people with anti-establishment views tend to hold more favorable opinions of populist parties. For example, in France, 34% of Right Populist respondents have a positive view of the National Front (FN), a right-aligned populist party, compared with 21% of those in the Right Mainstream.2 Similarly, in the Netherlands, there is a 17-percentage-point gap in favorability toward the right-aligned Party for Freedom (PVV) between the Right Populist and Right Mainstream groups. This pattern holds for nearly all populist parties asked about in the survey.

Still, ideology is the main divide on important policy areas, with smaller differences by populist views

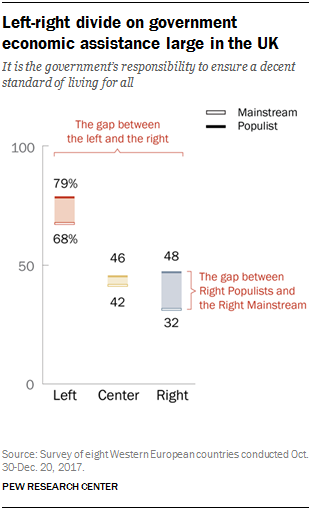

While populist views play a significant role in some key areas, the attitudinal differences between people who place themselves on the left and those who place themselves on the right tend to be larger across a range of major issues asked about. The left-right divide is particularly large on the issue of immigration, but is also quite substantial on attitudes about the role of the government in the economy. A clear illustration of this is the question of whether it is the government’s responsibility to ensure a decent standard of living for all or if it is the individual’s responsibility to do so. In most countries surveyed, respondents categorized as Left Mainstream are at least 20 percentage points more likely than those in the Right Mainstream to say it is the government’s responsibility. While in some cases the populist groups studied are more supportive of government assistance than those in the mainstream, the divide by populist views tends to be smaller than the ideological divide in most countries.

In the UK, for example, nearly seven-in-ten Left Mainstream respondents (68%) think the government should help people have a decent standard of living. About a third of the Right Mainstream agree (32%), for a difference of 36 percentage points. The gaps between the populist and mainstream groups at each point on the ideological scale are much smaller – a 16-point difference between Right Populists and the Right Mainstream, 11 points between the two groups on the left, and a statistically insignificant 4 points in the center.

Attitudes about political parties also largely determined by ideology

While people who are frustrated with the establishment are more supportive of populist parties than respondents in the mainstream groups studied, they have not yet abandoned traditional parties. Instead, people on the left – whether or not they hold populist views – tend to prefer left-leaning political parties, while those on the right prefer right-leaning parties. This pattern reveals that respondents with populist sympathies are not supportive of populist parties irrespective of ideology, but rather are supportive of parties that are consistent with their own ideological leanings.

To group political parties for analysis across the eight Western European countries, we divide parties into traditional and populist parties. We define traditional parties as those that have led the government – whether as president, prime minister or chancellor – at least once during the past 25 years, have competed in at least two national elections and still compete in elections today.

Populist parties are those that display high levels of anti-elite rhetoric and express a preference for direct democracy, according to the Chapel Hill Expert Survey (CHES). This survey asked regional experts to evaluate the party positions of 132 European political parties with regard to their left-right ideological leanings, key party platform positions and degree of anti-elitism, among other things. We also use the CHES to further group traditional and populist parties by ideology.

Finally, we discuss two political parties that are neither traditional nor populist, but that garnered at least 10% of the public’s vote in the most recent election preceding the survey and with which 15% or more of respondents identify as partisans. We analyze this subset of parties as a separate group called “other key nontraditional parties.”

For more details on how these party groups are defined and a list of where each political party is grouped, see Appendix B.

Despite its significant shift in the party system in the past two years, France provides a clear example of this dynamic. More than four-in-ten of both the Right Mainstream (46%) and Right Populists (44%) have a favorable view of the Republicans (LR), the traditional, right-aligned party in France. Fewer than two-in-ten respondents in the Left Mainstream (15%) and Left Populists (11%) feel the same. Both groups on the left have more positive views than either group on the right of the traditional, left-aligned Socialist Party (PS).

The two populist parties in France that are on opposite ends of the ideological spectrum – the National Front on the right, led by Marine Le Pen, and La France Insoumise on the left, led by Jean-Luc Mélenchon – appeal most strongly to respondents from their respective ideological camps who hold populist views. These two parties repel the populist groups on the opposite side of the ideological spectrum, however. For example, 68% of Left Populist respondents have a favorable view of La France Insoumise, while just 24% of Right Populists say the same.

En Marche – the new party that emerged with Emmanuel Macron in 2016 and is neither traditional nor populist – gets higher ratings from all three mainstream groups, as well as from the two populist groups in the center and on the right. Left Populist respondents are the most negative about the party.