A year after global opinion of the United States dropped precipitously, favorable views of the U.S. remain at historic lows in many countries polled. In addition, more say bilateral relations with the U.S. have worsened, rather than improved, over the past year. Among possible sources of resentment is the widespread perception that the U.S. does not consider the interests of other countries when making foreign policy decisions. More generally, relatively few see the U.S. stepping up more to solve international problems.

Some changes in U.S. image in last year, but no major recovery from 2017

In the 2018 survey, opinions of the U.S. vary greatly around the world, with enthusiastic ratings among people in Israel, the Philippines and South Korea, and unenthusiastic ratings in Germany, Russia and Mexico.

Divergent opinions of the U.S. are quite evident in Europe, where favorable views range from seven-in-ten in Poland to three-in-ten in neighboring Germany. Half in the United Kingdom have a positive opinion of the U.S., while only 38% in France agree.

Across the 10 European countries, views of the U.S. tilt toward the negative (a median of 43% favorable vs. 52% unfavorable).

Compared with the end of Barack Obama’s presidency, positive opinions of the U.S. have declined significantly in seven of the EU countries surveyed. This includes dips of 27 percentage points in Germany, 25 points in France and 11 points in the UK. However, favorable opinions of the U.S. have not changed much over the same time period in Poland, Greece or Hungary.

In North America, however, positive views of the U.S. are sharply down from the last reading in the Obama presidency in both Mexico (-34 percentage points) and Canada (-26 points). These have remained stable in the first two years of the Trump presidency.

Among allies in Asia, views of the U.S. have trended slightly downward since Donald Trump became president. Overall, opinions of the U.S. are quite positive in South Korea (80%), Japan (67%) and Australia (54%). Views of the U.S. are also very positive in the Philippines but mixed in Indonesia.

Across the 25 countries surveyed in the past two years, in 14 there was not a significant change in favorable views toward the U.S.

In five countries, there has been an increase in positive sentiment toward the U.S., most notably in Kenya (+16 percentage points), Spain (+11), Japan (+10) and Tunisia (+10).

The biggest drop in views of the U.S. since 2017 was in Russia, where only 26% have a positive image of the U.S. compared with the 41% who said this last year. However, only 15% of Russians had a positive view of the U.S. in 2015.

In 2018, an overwhelming number of Israelis (83%) have positive impressions of the U.S., but it is close to unanimous among Israeli Jews (94% favorable). Only 43% of Israeli Arabs feel the same way.

Among the three sub-Saharan African countries surveyed, views of the U.S. are very positive. In South Africa, favorable opinions of the U.S. are somewhat divided by race. Among white South Africans, 69% have a favorable view of the U.S., but only 56% among the black population and 54% among mixed-race people, also called “coloured” in South Africa, agree.

In Latin America opinions are mixed, with positive views of the U.S. among Brazilians and very negative views among Mexicans.

In 10 of the countries surveyed, young people ages 18 to 29 are more favorable toward the U.S. than those who are 50 years of age and older. For example, in Brazil, 72% of 18- to 29-year-olds have warm feelings toward the U.S. compared with 42% among those 50 and older, a 30-percentage-point difference.

Large double-digit differences by age also occur in such disparate places as Russia (+27 points), Spain (+20), Tunisia (+19), Germany (+16) and Argentina (+16).

In addition to differences by age, there are also gender divides in some of the countries surveyed. In most cases, it is men that have a more favorable opinion of the U.S.

For example, 46% of Canadian men share a positive view of the U.S. compared with only one-third of women. Similar double-digit gaps exist between men and women in Australia, Sweden and Spain.

Only in one country surveyed do women have a more favorable view of the U.S.: Tunisia. There, 42% of women have a favorable opinion of the U.S. compared with 32% of men.

Another consistent demographic difference on U.S. favorability is by ideology, with those on the right of the political spectrum expressing warmer feelings toward the U.S. than those on the left.

Israel stands out clearly as an example. Nearly all Israelis who put themselves on the political right have a favorable opinion of the U.S. (94%, vs. 57% on the political left). This 37-percentage-point difference is the largest ideological divide in the survey.

Those on the right are also more keen on the U.S. in Sweden (+26 points), Australia (+26), Spain (+21), France (+20) and the UK (+20).

Similarly, the U.S. is seen more positively among Europeans who have a favorable view of populist parties within their countries.

For example, among people in France who have a favorable view of Marine Le Pen’s National Rally (formerly known as the National Front), 57% have a positive opinion of the U.S. vs. only 36% among those who have a negative opinion of the National Rally. Similar divides exist among supporters and detractors of Alternative for Germany (AfD) in Germany; the League (formerly called the Northern League) and the Five Star Movement in Italy; UKIP in the UK; Jobbik in Hungary; and the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands.

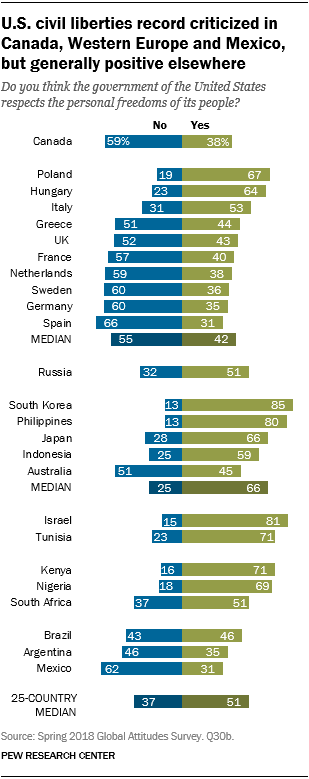

America’s reputation on civil liberties is still positive but tarnished among key allies

Across 25 countries where the question was asked, most say that the U.S. government respects the personal freedoms of its own people. But shifts, especially in Europe, show that people are more critical of the civil liberties record under President Trump than under prior administrations.

Europeans, along with Canadians and Mexicans, are the most skeptical that the U.S. government respects Americans’ freedoms. Majorities in Spain, Mexico, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, France and Canada all say that the U.S. fails to respect the rights of its people. Poles, Hungarians and Italians buck the European sentiment, with more than half in each country saying the U.S. does respect civil liberties.

In the Asia-Pacific nations surveyed, most people think the U.S. protects personal freedoms at home. Australia is the exception, with about half saying that the U.S. does not respect its people’s freedoms (51%) and slightly fewer (45%) saying it does.

In Israel, 81% say the American government respects personal freedoms, and 71% of Tunisians agree.

About half or more in Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa also have this view.

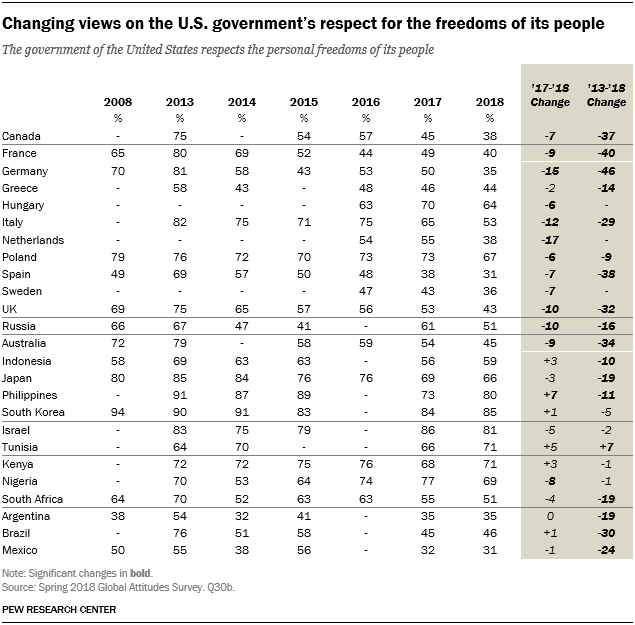

There has been a notable decline in European faith that the U.S. respects Americans’ rights since last year. In fact, among the 10 European countries surveyed, in all but Greece there has been a significant decline in those saying the U.S. respects personal rights, with the most dramatic falloff in the Netherlands (-17 percentage points).

Looking back over the past few years, far fewer people across the countries surveyed say the U.S. government respects personal rights. In fact, in 17 of the countries surveyed in both 2013 and 2018, there has been a significant downward shift in the share saying the U.S. respects its people’s rights. Only one country, Tunisia, has seen an improvement.

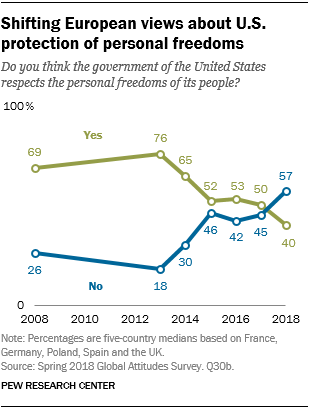

Views on whether the U.S. respects the personal freedoms of its people have shifted most dramatically among five European countries that have been surveyed since the Bush administration in 2008. Among these five countries (France, Germany, Poland, Spain and the UK) more now say that the U.S. government does not respect the personal freedoms of its people (a median of 57%) than say it does (40%).

The shift began in the sixth year of the Obama administration, after the National Security Agency spying scandal, but it has accelerated this past year. Since 2013, there has been a large increase in sentiment across these five countries that the U.S. does not respect personal freedoms, with a corollary fall among those who say it does.

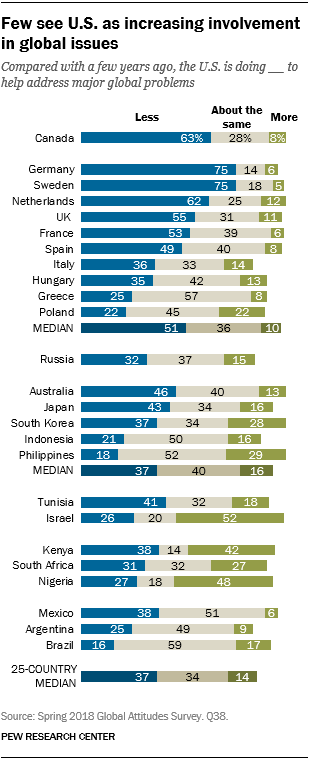

Only a small share says the U.S. is doing more to address global problems

When it comes to U.S. contributions to the global community, people are generally split as to whether the U.S. is doing less (median of 37%) or about the same as it used to (34%) compared with a few years ago. Only a small share (14%) believe the U.S. has increased its involvement.

The view that the U.S. is doing less to solve international problems is especially widespread in Canada and Western Europe. More than half say this in Germany (75%), Sweden (75%), the Netherlands (62%), the UK (55%) and France (53%). However, only a quarter or fewer in Greece (25%) and Poland (22%) share the view that the U.S. is retreating from the world stage.

In the Asia-Pacific region, opinion is more evenly divided between those who say the U.S. is doing less and people who believe its involvement in tackling international issues is little changed. In Indonesia and the Philippines, the prevailing view is that the level of U.S. global engagement is about the same as a few years ago.

Israel is the most convinced that the global role of the U.S. has grown in the past two years: About half (52%) say the U.S. is doing more to address global problems.

In sub-Saharan Africa, Kenyans are divided: 42% say the U.S. is doing more, compared with 38% who think it’s doing less. Nearly half of Nigerians (48%) credit the U.S. with doing more, while only 27% say the U.S. is doing less to help address major issues.

In the three Latin American countries surveyed, roughly half or more say that U.S. efforts are unchanged.

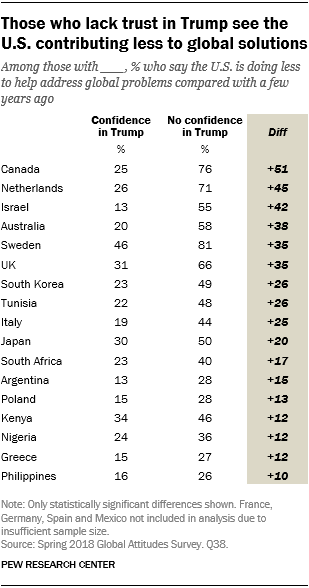

Views of American involvement in global solutions differ greatly depending on expressed confidence in President Trump. In 17 of the 25 countries surveyed, people who do not trust Trump to do the right thing in world affairs are significantly more likely than those who have confidence in him to say that the U.S. is less involved in tackling global problems. The magnitude of the difference is striking in some countries: There is a gap of at least 20 percentage points in Canada, the Netherlands, Israel, Australia, Sweden, the UK, South Korea, Tunisia, Italy and Japan.

Few say the U.S. considers their country’s interests

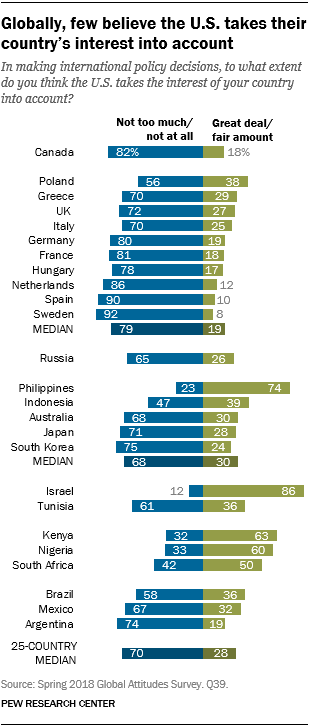

Across the 25 countries where the question was asked, a median of just 28% say the U.S. takes their country’s interests into account when making international decisions. In fact, majorities across Europe, and in neighboring Canada and Mexico, say that the U.S. does not take into account their interests when making foreign policy.

Perceptions of American foreign policy as not taking into account their country’s interests are also widespread in South Korea, where U.S. foreign policy has been especially active on the issue of North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. Three-fourths of South Koreans say Washington does not consider their interests.

Only in Israel, the Philippines, Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa do half or more say that the American government takes into account their interests a great deal or fair amount when making foreign policy decisions.

Since the question was last asked in 2013, 14 of the countries surveyed have seen significant declines in the share of people who say the U.S. considers their country’s interests.

The biggest decline has been in Germany, where half in 2013 said the U.S. considered their country’s interests, compared with 19% today – a 31-percentage-point drop.

Sharp declines also occurred in South Africa, Brazil, Mexico, France, Italy and Kenya.

In three countries surveyed in both 2013 and 2018, more people today think the U.S. considers their country’s interests: Greece, Tunisia and Israel. Among these, Israel saw the biggest increase, perhaps due to recent U.S. actions, such as scrapping the Iran nuclear deal and moving the U.S. Embassy to Jerusalem.

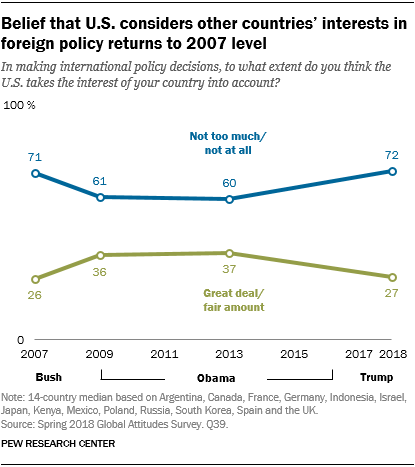

Looking across 14 countries surveyed in 2007, 2009, 2013 and 2018, opinions on whether the U.S. considers other countries’ interests have shifted under three different American presidents.

In 2007, toward the end of the Bush administration, a median of 71% across the 14 countries said that the U.S. did not take into account other countries’ interests when making foreign policy, compared with 26% who said the U.S. did. Attitudes shifted at the beginning of the Obama administration in 2009. Nations such as Germany (+27 percentage points), France (+23 points), the UK (+19), South Korea (+19) Canada (+18) and Russia (+12) saw double-digit increases in the share of people who felt the U.S. took their country’s interests into consideration. Yet, overall, a majority across the countries polled in both years still felt the U.S. did not consider their interests. By 2013, little had changed. Now, in the first reading of such sentiment in the Trump administration, a 14-country median of 72% say the U.S. does not consider their nations’ interests and only 27% say it does.

Most say relations between their country and the U.S. have not changed over the past year

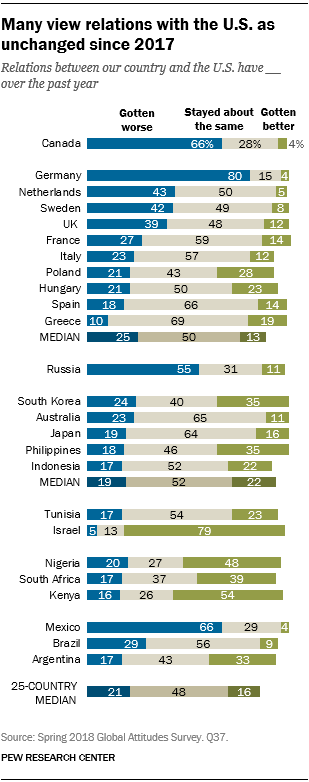

Although many believe that the U.S. does not take their country’s interests into account, relatively few describe worsening relations with the U.S. Pluralities in roughly half of the 25 nations surveyed say relations with the U.S. have remained stable over the past year.

Among those who have perceived a change in their country’s relationship with the U.S., slightly more believe that relations have worsened (median of 21%) than believe they have improved (median of 16%).

Canadians hold generally negative views of their relationship with their southern neighbor. Roughly two-thirds (66%) say relations have gotten worse while only 4% say they have improved.

Germans have the most negative view of their relationship with the U.S. Eight-in-ten say it has deteriorated since 2017. In comparison, at least four-in-ten in every other European nation say their interactions with the U.S. have generally stayed the same.

A majority of Russians also see their relationship with the U.S. as having soured. Roughly one-third do not see a difference over the past year, while 11% believe U.S.-Russia relations have improved.

On the opposite side of the spectrum, Israel has by far the most positive view of U.S. relations. Nearly eight-in-ten say their country’s relationship with the U.S. has gotten better.

Publics in sub-Saharan Africa also tend to see their relationship with the U.S. as improving. More than half in Kenya and 48% in Nigeria say things have gotten better over the past year.

Views in Latin America are more mixed. While pluralities in Argentina and Brazil say that relations have not changed, roughly two-thirds in Mexico say their country’s relationship with the U.S. has worsened. Their views are remarkably similar to those of America’s northern neighbor.