How Young Adults Want Their Country To Engage With the World

Focus group findings from France, Germany, the UK and the U.S.

Decades of cross-national surveys have found that younger people tend to be more internationally oriented than older adults. They usually have more positive views of international organizations and foreign countries and are more likely to prioritize international cooperation.

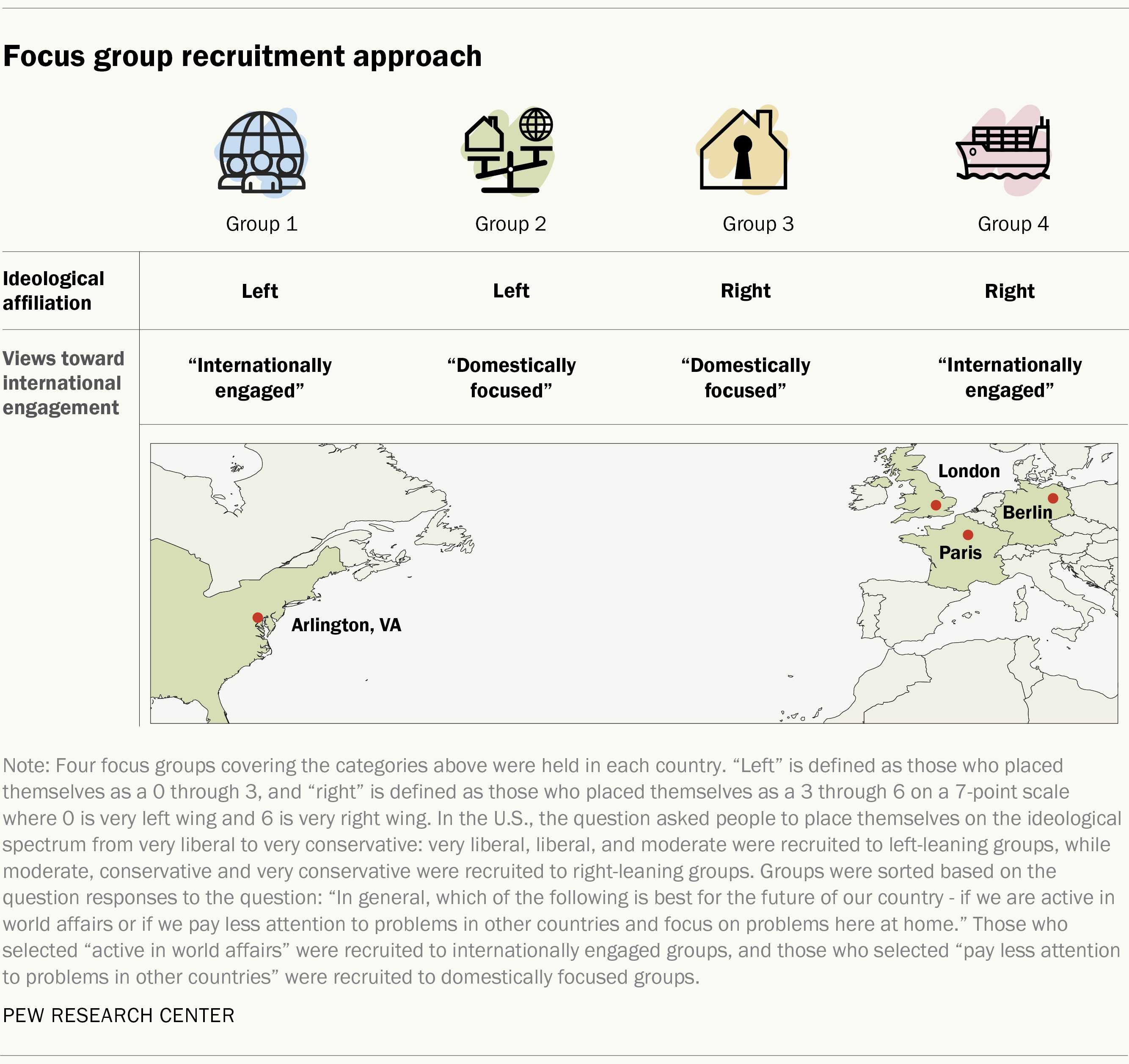

But young people differ from one another over how they want their country to engage with the world. Some feel their country has an obligation to people beyond their borders. Others doubt their country has the resources to pursue international actions. To better understand these perspectives, we conducted 16 focus groups with young adults in France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States.

In each country, there were four focus groups, organized around their participants’ ideologies and views on foreign engagement. Despite different histories and current political climates, four distinct attitudes about how best to engage with the world were consistent cross-nationally:

The left-leaning, internationally engaged groups emphasize the moral duty to be involved overseas. Still, there is a great deal of doubt about whether they can trust their government to get involved for the right reasons.

The left-leaning, domestically focused groups also feel a moral obligation to help overseas. But skepticism about their government and a widespread sense that their own country needs dramatic changes leads them to prioritize “getting their own house in order.”

The right-leaning, domestically focused groups see their country in a state of economic distress. They feel that their country’s resources are limited and that it is more important to focus on domestic issues than to send resources abroad – and that their country should strive for self-sufficiency.

The right-leaning, internationally engaged groups see their country as intertwined with others. They view international cooperation as benefiting their country’s economic and security interests.

Introduction

How younger adults want their country to engage in the world is closely related to how they understand their country’s current place in the world. Is their country well-resourced and morally obligated to work with other nations? Or stretched thin at home and unprepared for effective action abroad?

The focus groups took place in November and December 2022, against the backdrop of rapidly rising energy prices and cooling temperatures. As countries braced themselves for the first full winter following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, much of the conversation was refracted through the lens of the Ukraine crisis: Topics included domestic priorities centered on gas prices and the cost of living, as well as dealing with refugees, and international priorities focused on issues of energy and geopolitical incursions. Yet, how people understood these respective issues – and prioritized them – differed dramatically based on which of the four archetypical groups they fell in.

For example, people on the ideological left typically feel some level of moral obligation to help Ukraine, but also hold a deep skepticism of their own government’s role and motives. For those who prioritize international engagement, the desire to help Ukrainians – both in Ukraine and as refugees – can outweigh their concerns about their government’s ability to properly handle the crisis. For more domestically focused people on the left, a sense that their government makes things worse when it gets involved militarily often leads them to prioritize diverting money to help their domestic population. Right-leaning, domestically focused participants are more inclined to prioritize their own people first, but highlight the importance of energy independence. They also do not support sending “blank checks” abroad for limited perceived benefit. And right-leaning internationalists see the need to counter an authoritarian Russia, both for their own security and the security of the world order.

How views of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine vary across focus groups

Note: The typical position shown here is a simplification of the focus groups and reflects the cross-national themes that came up in each archetypal group.

Source: Focus groups conducted Nov. 8 – Dec. 7, 2022.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Domestic politics and people’s understanding of their own country’s history also heavily inform their thoughts about how their country should behave on the global stage. Historically distant events like empire, slavery and World War II still have modern impact, coloring which issues people say are moral obligations, how people think their country should work with international organizations and more. And recent events – whether it be the transition from Chancellor Angela Merkel to Olaf Scholz, the Jan. 6 insurrection in the U.S., the rapid leadership changes in the UK or even a bilateral summit between Presidents Emmanuel Macron and Vladimir Putin – color how people think about their country’s competency to act internationally.

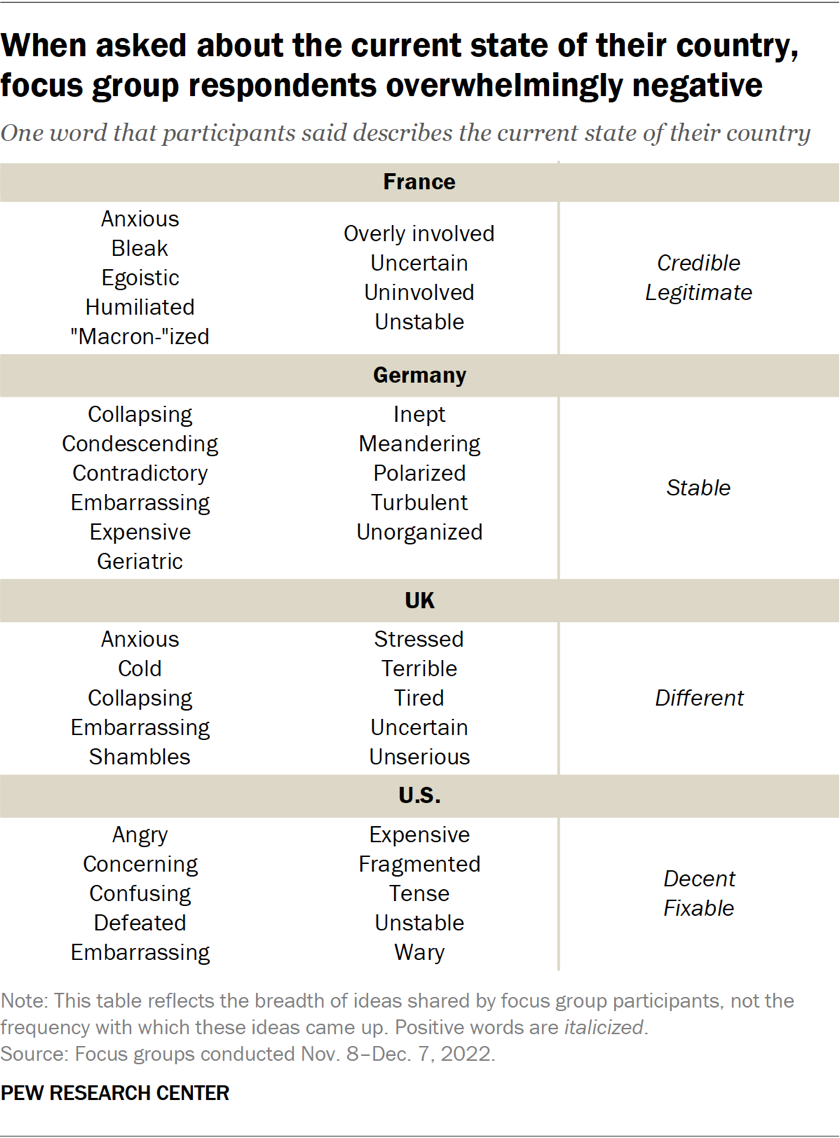

All told, the overall mood in the groups was one of political discontent, turbulence and apprehension – and, when asked to summarize the state of their country in one word, most focused on negative sentiments like “embarrassing,” “uncertain” or “shambles.”

Below, we’ll expand upon these themes in more detail, drawing upon the richness of 16 focus groups with 18- to 29-year-olds conducted in France, Germany, the UK and the U.S., as well as decades of findings from cross-national and U.S.-focused survey data.

Pew Research Center has been conducting quantitative research on views of international cooperation and multilateral organizations over the past two decades. This is the Center’s first in-depth project further exploring opinion on these topics using qualitative methods. We held 16 focus groups from Nov. 8 to Dec. 7, 2022, in or near the capital cities of France (Paris), Germany (Berlin), the United Kingdom (London) and the United States (Arlington, Virginia), with four groups per country. Groups were organized by ideological affiliation and views toward their own country’s involvement in world affairs. See the Methodology for more information.

The conversations among group participants were video recorded, transcribed and translated. The final data sent to Pew Research Center was anonymized. The Center analyzed the transcripts (in English) for key themes. Our analysis is not a fact check of participants’ views.

While we do highlight sentiments expressed by individual participants in the report, they are meant to be representative of the themes discussed in the group more broadly. Nonetheless, quotations are not necessarily representative of the majority opinion in any particular group or country. Quotations may have been edited for grammar, spelling and clarity.

Should countries focus overseas or at home?

A crane is positioned above new residential housing units under construction on Dec. 19, 2022, in Los Angeles. (Mario Tama/Getty Images)

While younger people are often more supportive of international cooperation than older ones, this is not always the case. In the U.S., young adults are more likely than older ones to say we should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on problems here at home than to say it’s best for the future of our country to be active in world affairs.

The focus groups were organized in part based on this concept: two groups per country with people who said it was better for the future of their country to be active in world affairs (“internationally engaged”) and two with people who said that their country should pay less attention to problems overseas and concentrate on problems at home (“domestically focused”). Both the “internationally engaged” and “domestically focused” sections were then split ideologically into left and right for a total of four focus groups per country. (For more, see Methodology.)

Below, we highlight the ways people thought about the trade-off between being active in world affairs or concentrating at home, as well as the relative pros and cons of being more internationally engaged or domestically focused.

Domestically focused young adults see domestic and foreign policy as ‘zero-sum’

Young focus group participants who prioritize concentrating on problems at home frequently highlighted the ways in which they perceive foreign and domestic interests as a zero-sum battle for resources. People felt that spending less abroad could mean more funding for health care or education. Others felt “ignored” because of their government’s focus on Ukrainians at the expense of its own citizens. One left-leaning, domestically focused German woman described it this way: “Ukrainians are being preferred at the moment. Perhaps this means that our government should care more for our own citizens.” One French woman even questioned the notion of whether France is as rich as it looks on paper, given the inequality in the country, saying, “We are supposed to be a developed country, one of the world powers, and we still have buildings collapsing in France … we are not able to take care of ourselves. We will only be able to help internationally when we have political and social stability in our own country.”

Domestically focused young people want to ‘get their own house in order’

These feelings extended to a general interest in fixing domestic problems before focusing abroad. A woman in the U.S. passionately declared, “We should go back to that good old-fashioned 1800s isolationism policy and just be like ‘our country is a hot mess.’ Can we just pause for a second with all the world wars and just fix up shop here? Because we’ve got some serious issues at home.”

“It’s hard for people to believe in what you’re saying internationally if everything in your own country doesn’t seem to be positive.”

Woman, UK, right domestically focused

Some were concerned that if countries don’t have their acts together domestically, they’ll be seen as hypocritical or moralizing. In the UK, a man felt it was important to “get Britain’s house in order before we can go abroad and lecture other people about what to do with their own place. Because things are such a mess here and they have been for such a long time, I think we need to concentrate all our energy and resources to helping people out here first because, you know, people are not able to afford their heating, not able to buy their own places, wages are stagnating … that’s more important than lecturing other people about what they do in their country.” An American man echoed this sentiment: “The United States likes to present itself as the arsenal of democracy, this whole ‘city on a hill’, this ‘we are an example to others’ type of ideal. But then when we go out and tell some other country to do this or that, they can point to us and say, ‘well you have all these other issues at home and you are trying to tell us how to do things?’”

Left-leaning young people see their country’s overseas involvement making things worse

Left-leaning, domestically focused groups often highlight the importance of focusing internally because of poor outcomes in the past when their country had been internationally engaged. Per one British man, “Whenever we’ve gone into other countries, what does that look like? How did those countries turn out? Normally, not well.” One German man, for example, highlighted how he felt like Germany was exacerbating conflicts in other countries by selling their weapons overseas. An American woman described America’s involvement overseas serving as the “world’s policeman” sarcastically, saying, “Let’s just pass on some of this democracy stuff to everyone else and destabilize them a little bit. They’ve got oil, right? Like, it’s fun, it’s fun for everybody.”

“I think we should just be more appreciative of other people’s cultures and their countries instead of charging in like a savior and completely disregarding all of that.”

Woman, UK, left internationally engaged

Even some internationally oriented left-leaning participants are skeptical about how and why a country gets involved. One French man noted, “My opinion on the government today is not that it’s uninvolved but rather that it gets involved in the wrong way. Meaning there’s a lack of coherence.” His critique – echoed by many left-leaning, internationally oriented participants – was not that the government was handling all issues badly or that it should be doing less. Rather, that in focusing on certain issues – e.g., Ukraine – it has become more evident where the government is not taking a stand. For example, one British man noted, “It’s positive the way we intervened in Ukraine to an extent, but I think it’s negative the way those decisions are made. We turn a blind eye to lots of other awful things happening. We’ve got a great relationship with Saudi Arabia despite their appalling human rights record … I think we’re quite hypocritical in that way, not always making the right decisions.” The examples regularly cited – such as prioritizing Ukrainian refugees over African or Syrian ones – or defending Ukrainians but being unwilling to take a stand for the women protesting in Iran – often involved implicit or explicit accusations of racism on the part of the governments. Some also accused their governments of being relatively weak and unwilling to stand up for human rights when there is a high economic cost, such as defending the Uyghurs in China.

Even young adults who emphasize problems at home don’t want to be isolationists

Still, not all participants who say it is more important to focus domestically feel that way at the expense of international engagement, stressing that they are not “being completely isolationist.” Rather, they noted that it is a question of degree and prioritization. One British man declared: “It’s not that we don’t want to cooperate and be involved in world affairs at all. But, I think if we were to evaluate where we should put most of our focus, it’s more important that we sort out domestic issues.” Participants who prioritize a domestic focus still often foreground the importance of working through international organizations – particularly the European Union in the case of France and Germany, but also NATO in the U.S. and UK.

“It’s not, like, being complete isolationists. But as the world has become more global and we’re facing more crises … I think it’s about being able to take care of the people we already have here.”

Man, UK, left domestically focused

Much of this stems from the often shared notion that problems do not stop at the water’s edge – or that international issues have domestic “knock-on effects,” as one British focus group repeatedly stressed. Even domestically focused participants recognize that many domestic problems are caused by global phenomena, including climate change, supply chain issues, COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. One American man mentioned the war in Ukraine, noting, “We saw how quickly it affected gas prices here at home and food prices. Instability on the global market is something I think a lot of people are detached from until it comes back very quickly, whether we like it or not. We’re a very global society now and any instability on the global level comes back to affect us.”

Still, the recognition of “knock-on effects”– particularly because of the war in Ukraine – prompt two very different possible solutions. Some domestically focused participants – especially on the right – see the importance of becoming self-sufficient. In Germany, concerns about how “vulnerable” the country had become due to dependence on Russian oil led to calls in the right-leaning, domestically focused group to “do it ourselves, produce it ourselves.” Britons came to the same solution: “If they’d reinvested all the money we’ve spent on Ukraine into energy production within the UK … we could just reduce the risk of Russia as a whole.” In the U.S., right-leaning, domestically focused participants stressed the importance of drilling and domestic energy production and in France, too, right-leaning, domestically focused participants noted that when it comes to energy, it’s important for “France to become sovereign on this topic.”

“The problems elsewhere have consequences at home, so it’s better to have a position on them and an influence in their resolution.”

Man, France, left internationally focused

In contrast, internationally focused participants reached the opposite conclusion: Since problems don’t stop at the water’s edge, collaboration and international engagement are essential. Per one British man: “Ukraine has had a massive impact on the cost-of-living crisis in the UK and I think for me, since an externality in a different country impacts our day-to-day life here, if we were not active in supplying weaponry, emergency support … it’d be even worse for the day-to-day living in the UK.” One man specifically highlighted that Europe “suffered the consequences of the choices of other powers, such as the U.S. under Donald Trump” but since his “decisions had a direct impact on Europe” it’s important to get involved so as not to “suffer the consequences without doing anything.”

Internationally engaged young people see benefits and moral obligation to focus overseas

Internationally engaged participants also tend to stress tangible domestic benefits stemming from such engagement. For example, one French woman said that if the country is closed off, it becomes “a place people don’t want to go to, don’t want to study in, don’t want to invest in, and it’s something that isn’t attractive on the international stage.” Others see the security benefits because of collaboration, intelligence sharing and working with allies. One German man, for example, stressed that no one in the country should be “under the illusion” that the German military can defend itself against Russia on its own and that safety and security are, in part, because of European collaboration.

“I think about NATO and our alliances and agreements abroad that protect us from things we may not be able to see at home … our involvement across the world in preventing threats can make us safer here.”

Man, U.S., left internationally engaged

Participants also often evoke a sense of largesse: They see their country as affluent and able to help the world and thus feel like it should do so. “As a wealthy nation, the U.S. kind of has a moral duty to promote our social causes across the world and fund initiatives to help the developing world and promote kind of a baseline human rights cause,” said one U.S. man. The specific moral obligations varied widely, too: Some noted the importance of collaborating on climate change “because we all live in the same environment,” while others stressed the importance of taking an active stand on human rights or anti-poverty initiatives. But the discussion was often focused on how people wanted their country to appear on the global stage. As one British man put it: “It’s part of our duty to care what’s going on overseas … it reflects us as a nation, as a people.”

What do young people want their countries to focus on?

The Gardon River dries up during a drought on Aug. 13, 2022, in Anduze, France. (Patrick Aventurier/Getty Images)

While climate change is an overarching international priority for all young adults, other international priorities vary. For domestically focused young people, energy independence (for those on the right) or diversification (for those on the left) in the wake of the war in Ukraine is a particularly urgent matter. Internationally engaged people also see the value of working with allies and international organizations to solve various world problems via their country’s relative power and diplomatic strength – particularly in France and Germany.

How views of international priorities vary across focus groups

Note: The typical position shown here is a simplification of the focus groups and reflects the cross-national themes that came up in each archetypical group.

Source: Focus groups conducted Nov. 8 – Dec. 7, 2022.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Young adults think climate change requires a global solution

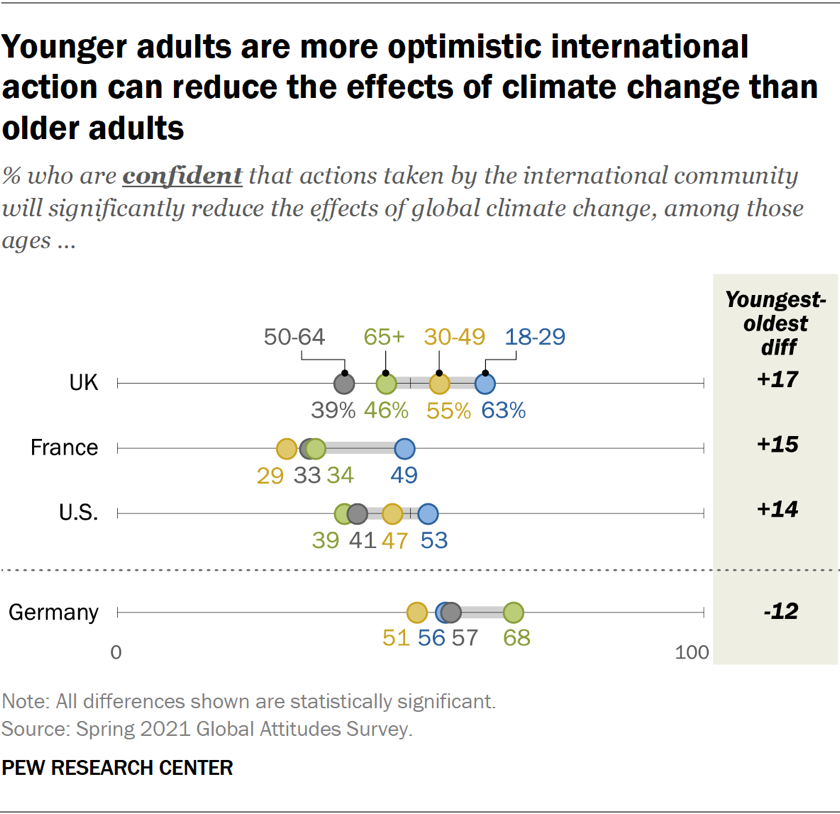

Past Pew Research Center surveys have found that young adults in these countries tend to be more concerned that climate change will harm them personally, as well as more optimistic about the global community’s ability to deal with climate change and more likely to see efforts like the Paris climate agreement benefiting their country’s economy.

Climate change is a top-of-mind issue, as many participants see it impacting all nations in the world. As one internationally engaged British man said: “I suppose it comes back to morality … We sort of have to work together, we’re all living in the same environment after all, so it’d be better if we worked together on that front.” Participants noted that they, as young people, diverged from older people on this issue. One French woman, for example, framed older people’s view of climate change as being a “value” – more of an ideal one can choose to pursue or not, noting that younger people, like herself, knew climate change to be a “problem” – something pressing that needs an immediate solution and can’t be put off.

Even domestically focused groups see climate change as an issue where they were willing to engage with other countries. “There’s no way of dealing with climate change as just us because we’re going to be by ourselves,” said one woman in the UK. Still, this recognition could carry resentment that one’s own country is shouldering too much. For their part, Europeans often wanted to see more from countries like the U.S. and China on climate change – sometimes emphasizing that domestically, they were doing enough and that the issue lay elsewhere. “The problem is that many countries, such as the U.S., are not listening to science and don’t care at all,” said one German man. While left-leaning Americans called for the U.S. to do more, most Americans also fixated on the need for other high emission countries like China and India to be held accountable. “We should absolutely be working with other countries, but we have to actually expect them to hold up their side of the bargain, which we have not done … we cannot let these countries that have no motivation to change their ways continue to just rule the day and do whatever they want,” said one conservative U.S. woman.

Right-leaning, domestically focused young people often stress energy independence

Another key issue younger people want their governments to focus on, particularly in Europe, is diversifying their country’s energy supply – both in type and away from Russia. Past Center surveys have found that younger people are more likely than older ones to oppose expanding the use of natural gas, and in France and the U.S., they are also more likely than older people to say increasing production of renewable energy should be prioritized over increasing fossil fuel production.

“The war in Ukraine has had a knock-on effect on us with the fuel, the energy. Obviously, this is the worst winter that the UK has had and people don’t know if they can keep their homes.”

Woman, UK, right internationally engaged

The war in Ukraine and resulting impact on the world’s oil supply created a sense of urgency. “It showed me how vulnerable we are because we’ve relied on Russia far too much. I don’t want that anymore in the future, that we are so dependent on one country,” noted one German woman. In France, another woman expressed frustration with the French response to Ukraine being insufficient as France waffled about whether it needed Russian oil: “In the beginning, France didn’t really know where to position itself, knowing that Russia is the first energy supplier in Europe … they didn’t clearly state their position, and it’s only later that they did an about-face and said they were totally with Ukraine.”

However, solutions diverge. In right-leaning, domestically focused groups, becoming completely independent in energy production is a goal, with any international cooperation being a means to an end. As one French woman put it: “Strategically, we should ally with countries that can supply us with what’s needed while France does what’s necessary to be independent.”

Overall, internationally oriented young adults prefer a diversification of energy sources

Those on the ideological left, on the other hand, stressed the importance of diversifying energy sources – both suppliers and types. “We have seen the consequences of dependencies in the energy supply when you have one main supplier only. In this case, our foreign policy should become even more proactive, because we can see what happens when you rely on one supplier,” said one German woman.

“I would favor diversification, meaning sourcing products from various countries and not only gas from Russia by gas pipelines or from China, even though it might be cheaper at first glance.”

Man, Germany, right internationally engaged

Alternative energy is a particular focus for internationally engaged or left-leaning participants, who often tie it back to the issue of climate change. Some described the need to reinvest in infrastructure, whether it be wind or solar, or to “try to overhaul our current infrastructure to be more green.” France’s nuclear energy capabilities also factored into discussions. French participants saw it as a competitive advantage – especially vis-à-vis Germany – and Germans largely agreed. “France is also a good example when it comes to energy policy and also energy prices. They have just capped the energy prices. And when it comes to energy production, they still use their nuclear power plants. And you can even refurbish the used materials and mix some fresh material and implement it to the nuclear power plants again,” said one German man.

Americans largely do not feel the impact of Russia on their energy supply as acutely as Europeans. Still, internationally engaged people see the situation in Europe as a cautionary tale. One American man said, “I think one thing Russia has done during the war is use their economic ties with the West to kind of gain leverage over them … they have the Nord Stream 1 and 2 pipelines and it has made Europe reliant on Russia for oil and gas.” For right-leaning groups, this led some to call for ramping up domestic energy production. One American said that if the U.S. boosted domestic production, “We can be a trade partner that is an energy exporter of all kinds that allows other countries to feel safe when they … come to the table to get energy.”

Internationally oriented young adults want their countries to be leaders in diplomacy and mediation

Many also want their country to be a leader in diplomacy and mediation. This especially came up in France and Germany. “I find it good that France often plays the role of mediator between different countries, actively but all while being conciliatory, it enables it to take stronger positions on certain subjects, including … Qatar and Russia,” said one French woman. Young French people specifically see their country’s ability to help mediate between the U.S. and China. As one French man said: “because we are a third power as Europe, even if we use it very poorly. We could try to find common ground and we have enough power then to force them to listen to us and find solutions.”

Germans also mentioned seeing themselves as mediators – a strategic advantage their country can play up to get more involved in the global community. As one man said, “Germany has a very positive image in almost all the world and there are few conflicts where Germany wouldn’t be accepted as a mediator or as a diplomatic player, that we utilize that more strongly and get more involved.”

U.S. survey data shows that younger Americans tend to be less likely than older adults to say that the best way to ensure peace is through military strength, and more likely to favor diplomacy than older people. And, in focus groups, this emerged: Internationally engaged Americans on the left were particularly keen to engage diplomatically and reduce military spending, collaborating with multinational organizations in the interest of preventing conflicts. Still, some in right-leaning American groups felt that diplomacy itself was best accomplished when military strength backed it up: “We can still negotiate at the table, because we can focus certain military actions, because we are capable. As soon as we lose that role, we don’t have that much left.”

How do young people want their country to engage with international organizations?

The United Nations headquarters building stands behind world flags on Sept. 19, 2022, in New York City. (Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

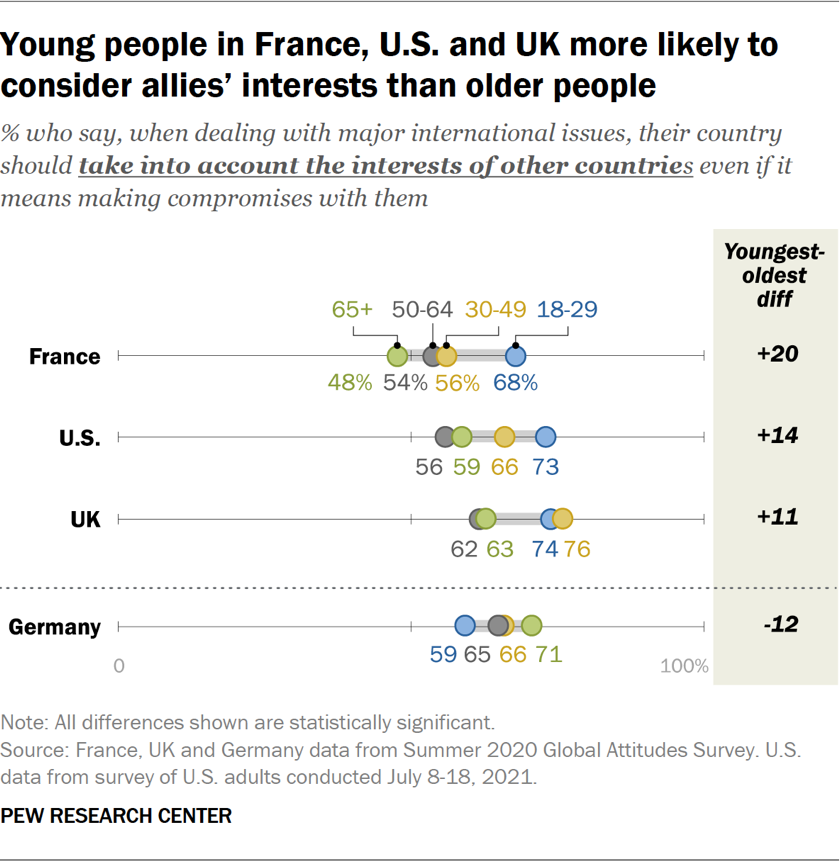

Past polling data suggest that young adults are more willing to engage with the international system than older adults. For example, they have long tended to have more positive views of both the EU and United Nations. They also tend to prefer taking into account the interests of allies or other countries – even if it requires making compromises.

While many young people across focus groups see the value in international organizations, some are skeptical that the benefits of organizations like NATO, the EU and to a lesser extent, the UN are not worth the costs. Internationally engaged people on the left and right see membership in most organizations as critical for increasing their country’s position on the world stage, while domestically focused people tend to be much warier of their potential drain on resources.

How views of engaging with international organizations vary across focus groups

Note: The typical position shown here is a simplification of the focus groups and reflects the cross-national themes that came up in each archetypical group.

Source: Focus groups conducted Nov. 8 – Dec. 7, 2022.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Internationally oriented young adults see organizations as a way to increase their country’s power and security

“Acting multilaterally is stronger than acting alone. Russia’s economy wouldn’t be nearly as crippled if we weren’t acting with the UK and the EU and all our other partners.”

Woman, U.S., right internationally engaged

Many young people see membership in international organizations – especially EU membership – as adding legitimacy to their own country. This was the case even among UK respondents in the wake of Brexit. One French woman said, “A presence on the international scene gives us weight, enabling negotiations, be it within Europe or in the world.” In fact, rather than worrying about diluting their country’s influence by collaborating with others, participants highlight how international engagement amplifies their power. “The fact that France, with the euro and the EU, we have an important place, we make important decisions and we are heard. We make influential decisions, so with meetings, G20 and all that, it’s a positive point internationally,” said one French man. Some internationally engaged Germans even entertained the idea that superpower status could be possible, but only through the EU.

In the UK, particularly among internationally engaged people, the absence of EU membership is felt as an acute loss. “We’re a lot less powerful now, on our own, than we were as a group. We’re not around that EU table anymore to make decisions on behalf of the EU either, and so we’re not in a position to be leading in the sense of preaching to other countries about what they should be doing,” said one British man. While many young people in the UK still wish to be part of the EU, their aspirations for more influence do not extend to superpower status. As one UK man put it: “I think we’ve probably overstepped that boundary maybe a few too many times, so probably best staying out of it for the foreseeable future.”

Right-leaning young people particularly value security-focused organizations like NATO

“I didn’t realize how important NATO was … if you attack one member, it’s treated as if you attacked the U.S. … I didn’t realize how powerful they were.”

Man, U.S., right internationally engaged

Young people also see international organizations as uniting countries in order to address security concerns and collaborate on common problems. For example, NATO’s ability to keep member countries safe is seen as its primary advantage and is praised, in particular by people on the right. “… Even though we’ve come out of the EU, we’re still a part of NATO. Places that are bordering Russia, they obviously want to become a part of NATO to protect themselves,” said one British woman. “I think about NATO and our alliances and agreements abroad that protect us from things we may not be able to see at home but are threats that could rise,” said one American man. Many recognize the institution as a key part of deterring Russia, with one German man saying, “If Ukraine had already been a member of NATO, Russia wouldn’t have attacked Ukraine, because the Russians know exactly that if a NATO country is attacked, all other NATO members are obliged to protect it.” Even domestically focused people often recognized that while NATO carried costs and risks, it was worth it for the security: “We’re willing to pay that premium for the protection of NATO.”

Despite seeing some benefits, domestically focused young adults are more critical of EU

Despite some of the touted benefits, domestically focused young people are somewhat more critical of organizations, including the EU. One French focus group, for example, debated the merits of leaving the EU. While participants were quite divided over it, many were frustrated about a lack of autonomy: “We’re not capable of making our own decisions without receiving a nod or approval from the EU … I feel like we suffer, more than anything else,” said one French woman. In Germany, some expressed frustration with the minutiae of EU regulations, such as cucumber curvature. One man suggested getting bogged down with these regulations hampered the bloc’s ability to influence the world: “That’s the problem, the EU has to act much faster, no principle of unanimity, so that you can actually utilize your strengths as a global player.”

Those on the left praised the UN in the abstract but argued for its reform

The UN, too, garnered criticism. Overall, it occupied a lesser status in people’s minds compared with the EU and NATO. And while people generally mentioned it positively at first blush, when they started to discuss it in detail, they often called for its reform. Germans, in particular, stressed the need to reform veto power – standing out as the only country in which focus groups were held that did not have UN Security Council membership: “The United Nations should be revolutionized, and the veto rights of China, Russia, France and America should be annulled. This no longer corresponds with how we are now living 80 years after the war. If one party doesn’t agree, which will be quite often the case now with Russia, then things aren’t implemented.” Another man noted the “authenticity and legitimacy” of the UN was undermined when Russia was both invading Ukraine and retaining its permanent seat on the Security Council.

Some were also concerned the UN was toothless: “The problem is that the UN just isn’t doing anything about climate change because they don’t want to do anything about it. Because as long as they can make more money, as long as the countries within the UN can make more money, they’re not going to do anything about it,” said one U.S. man. A British woman questioned any international organization’s ability to counter a country like China: “They’re just too big and powerful for any world organization or any country to really tell them what they can and can’t do.” Still, given the global nature of climate change as a problem, people still felt a desire to work collaboratively – including through the UN – mainly calling for more engagement and more efficacy rather than going it alone.

How does history shape current views of global engagement?

Berliners and people from all over Germany celebrate on the Berlin Wall on Nov. 11, 1989. (dpa/picture-alliance/dpa/AP Images)

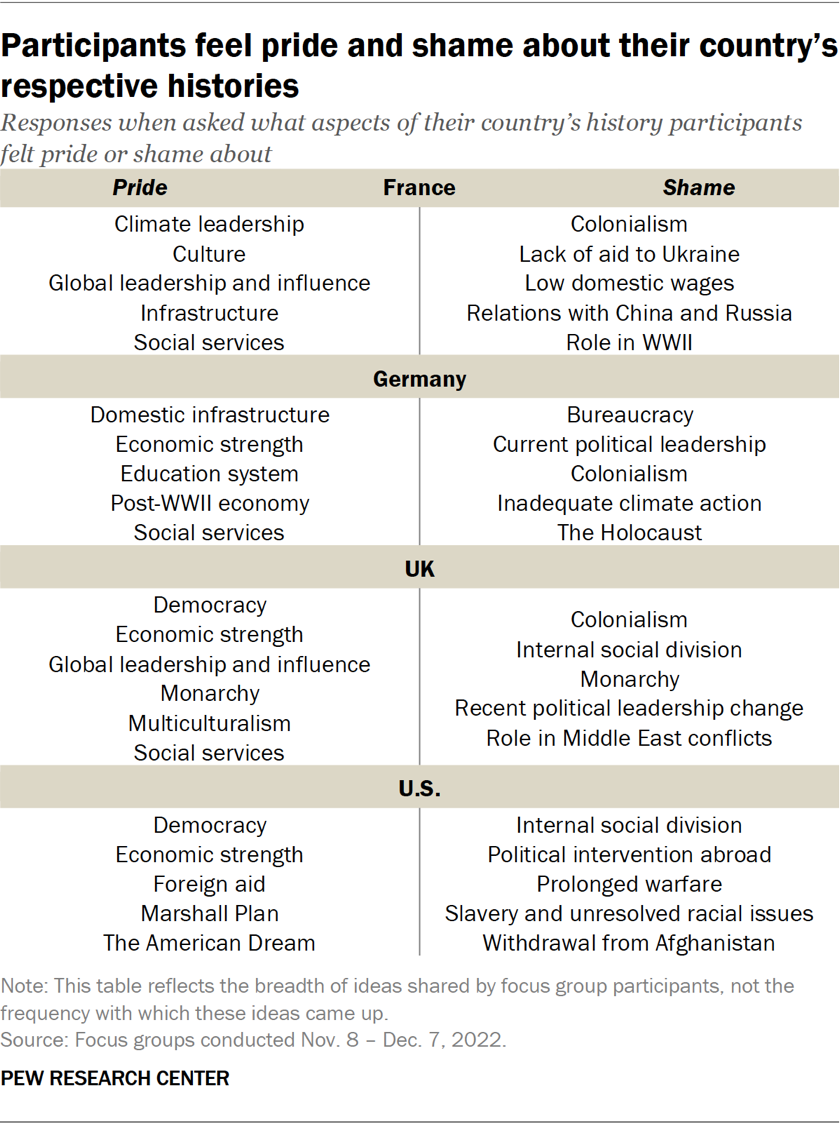

Younger people are less likely to feel proud of their country than older people – and, especially in the U.S., they are more likely to be ashamed of it than their elders. Part of this relative lack of pride may stem from a different interpretation of their country’s place in the world and its history. Younger Europeans, for example, were much less likely than older ones to say that their culture is superior to others when they were asked in 2016. Similarly, younger Americans are much less likely than older ones to say that the U.S. stands above all other countries.

In the focus groups, opinions differ over what is pride-inducing and what is shameful in their countries’ histories. But one thing unites the groups: How people understand their country’s past role in the world heavily influences what they think their country should do – or not do – when it comes to its current foreign policy.

Left-leaning, internationally engaged participants see a need to actively work overseas because of historical debts – whether due to empire, past slavery or other factors. Some of the policies they highlight are providing foreign aid because of past interventionism or accepting climate refugees because their countries got rich while polluting heavily. While left-leaning, domestically focused participants often feel a similar moral obligation, they emphasize helping those in their country who are affected by their governments’ past behaviors, such as working on racial justice in the U.S. or bettering the lives of immigrants from former colonies in France and the UK. These left-leaning, domestically focused participants also think that their country’s past behaviors mean that they should not be a leader internationally because to do so would be hypocritical.

Right-leaning, internationally engaged participants often note the negative role their country has played in history but want to also emphasize the positive: the development of science and technology, the spread of democracy and more. These people tend to see a global role for their country that stems from points of pride. Right-leaning, domestically focused participants, too, want less of a focus on the negative parts of their history and see the benefits of moving on, being proud and projecting strength. Some even felt that focusing on the negative parts of history could make their country look weaker to adversaries.

How views of history vary across focus groups

Note: The typical position shown here is a simplification of the focus groups and reflects the cross-national themes that came up in each archetypical group.

Source: Focus groups conducted Nov. 8 – Dec. 7, 2022.

PEW RESEARCH CENTER

Left-leaning young adults see a global debt based on their country’s history

In the UK and France, the history of empire and colonialism looms large. People who feel shame about their country’s overseas activities often have a sense of modern-day obligation. As one man stated it, “We’ve taken plenty from other countries so we should do our bit and give back to the world financially.” Some even highlighted how the UK’s history of pollution during its development is a debt that the UK should now pay back by being a leader in combating global climate change.

“It shapes modern Britain. You wouldn’t have Afro-Caribbean, Indian or Pakistani people in this country unless it was for colonialism … So it’s like built into the fabric of this country.”

Man, UK, left domestically focused

In France, left-leaning participants who feel shame about colonialism issued calls for France to take specific actions, such as repatriation of art and culture, reparations and financial aid for the former colonies or improving life for French citizens who emigrated from parts of the former empire. As one woman described it, “As colonial masters, France has some level of obligation to its colonies after using their lands and people. I believe we must give them some form of compensation and get out of their business.”

The importance of stepping back and listening to what the former colonies want, rather than getting involved from a position of “we know best,” is also salient for left-leaning participants in France and the UK. For example, one British man cautioned that the UK should not “go out preaching to the world” and should listen rather than moralize, given the country’s “horrible legacy” that is not even fully acknowledged. In France, another man noted that “by asking the countries in question that are still affected today, we can repair what is left to repair.” There is also a particular concern in domestically focused French groups that France is still meddling overseas in ways that it should not be.

Some left-leaning Americans also feel the U.S. should be ashamed about its domestic past and present – especially related to slavery and modern race relations – and thus do less overseas. One man said, “I was thinking that because of racial issues at home, it ends up making us look weak and divided globally. Since we have so many ongoing arguments within the U.S., we end up looking weak to other countries because we can’t solve issues within ourselves.”

Left-leaning participants also see a moral obligation to get involved internationally on the areas where they are proud of their country, largely centering on issues of infrastructure, health policy, law and culture. In Germany, for example, the sense that Germany was a leader in health and education led some to want to assist overseas: “When you do it better than other countries, you can support them.” Some also stressed the ability to serve as a positive role model: “I think our health system could have a very good influence on other countries … in terms of the health system, we can hold our head a bit higher.” Americans highlighted the country’s history as a leader in science and technology, specifically highlighting how the country did – and should – play a role in vaccine manufacturing and distribution to mitigate the COVID-19 crisis. And Britons regularly mentioned the National Health Service as a point of pride and noted that they could contribute globally in the area of health care. In France, the particular emphasis is on French culture, which people often stressed was unique and valuable for the world. For example, left-leaning people noted France’s history of demonstrating for rights and felt France should be a leader internationally in fighting for these same values: “It’s very much connected to history, we went through a revolution to have more equity between people … I’m not saying we should impose our values everywhere, but we have defended values that have seemed important to us, and those values should be communicated to countries that need it or aspire to it.”

Right-leaning young people want more focus on the positives of history

But not everyone sees empire in negative terms. For Britons who see the more positive aspects of empire – e.g., the spread of English, wealth and clout – there is more of a focus on how its imperial past can positively inform the UK’s modern-day behavior. One man noted that Rishi Sunak taking over as prime minister may help to smooth relations between Britain and India. Others cited how the Commonwealth can serve almost as a “political weapon,” uniting countries together and giving the UK particular influence among its democratic allies. Participants also noted how the UK can use its historical relationship with these countries to improve trade relations between former colonies. And the nuance that empire may have been awful, but it brought benefits was shared by some, such as one man who noted: “If you looked at us as a whole, if you took away empire, would we still all have the same technology and income? I don’t think so at all. It gave a boost to the UK in stuff like that … I think everybody recognizes how much of an awful thing it was, but the atrocity is that we did it, and I think there are people that have to sometimes accept that we’re able to live the lives we are now because of that as well. So, you have to accept the awful but also the benefits.”

“I think our identity politics issues here can be played on and then judged by countries abroad … it makes us look weak.”

Man, U.S., right domestically focused

And, in right-leaning American groups, shame about America’s history with slavery and racial injustice was less centered around America’s actual racial policies and more that the U.S. looks weak because people are overly focused on America’s past. One woman summarized it, saying: “I feel that a lot of times the media plays on the race issue … history is history, you learn from it, we’ve built from it, we’ve moved on … so I feel like the race thing is so played on by the media and the issue is not as big as it seems.” Another man noted: “It’s not the legacy of slavery that’s the issue. It’s how we are responding to it now … I am more ashamed that we still haven’t figured out our differences from stuff we fought a civil war over … other countries can use that to make us look like we are still thinking about slavery over here and we’re not. We are past that. It can be exploited by other countries.”

Right-leaning American groups were also somewhat frustrated that focusing on the flaws of American democracy might mean missing an opportunity to be a leader: “Democracy is the best system of government we have and we should not be ashamed of that. And it is clearly the system of government that has helped the most people and brought them out of depression.” Still, this was in sharp contrast to left-leaning groups who argued that the U.S. was not a good model for democracy abroad and should not focus on democracy promotion – or even leading by example – because, as one man said, “if half the country is going to reject an election and not accept the results, that’s not a good sign of democracy.” Another woman highlighted how Jan. 6 was “embarrassing and frustrating” and clearly signaled that the U.S. could not be an example abroad when the Confederate flag was being paraded around in what should have been one of the most secure buildings in the country.

For young Germans, the country’s World War II legacy leads young people toward international collaboration over pursuing superpower status

Germans across the ideological spectrum largely prioritized the same lesson from their history: They need to work collaboratively with other countries, building Germany’s clout as a diplomatic leader and working through the EU, rather than trying to be a superpower. One man explained it by saying, “There were two world wars because of too many superpowers on the battlefield. That’s why there were conflicts. In any case, we should involve ourselves a lot more internationally, become much more engaged …” but stop short of doing it alone or acting independently like the U.S. Another woman described Germany as having to “react differently” precisely because of World War II: “Other countries can be very strong and offensive. We have to be more diplomatic because of our past and our history.”

“We are not allowed to and should not have a strong political opinion. So, what remains? Being diplomatic, an arbiter.”

Man, Germany, right domestically focused

Young Germans also bemoan German politicians’ inability to escape the Nazi label, which in turn affects what the country can do. One man highlighted that it would “be nice if we didn’t have to think of the consequences of every word a politician says. Could this perhaps be associated with something from the past? So, can we tell Israel they are making a mistake without them thinking we are Nazis?” Some even felt that the onus of this historical burden was impeding Germans from feeling pride in or recognizing the accomplishments of their country. “It’s no question that the Holocaust and the Nazi regime are still our past and we have to deal with it. It influences our foreign policy and how we present ourselves as a nation, whether it’s simple things like national holidays or – and I sometimes regret this – the heavy burden we inherited. I feel we’ve lost some of our pride here. Those were dark, dark times but we’ve got a lot of good sides as a country, like how we’ve rebuilt ourselves, what we’ve done … I think there’s not very much balance.”

Despite the prominent role it plays in shaping how people think Germany should behave internationally, the Holocaust was almost never raised as a point of shame in the focus groups without moderator probing. One woman explained that she did not mention it because you “talk about this at school every year, it’s something that is intertwined with the German identity and always will be … there’s no need to mention it because we all know it anyway.” Others were frustrated about having to talk about it because they did not “identify with the events from the past” and thus felt apologies for past generations’ behavior were not their responsibility. Part of these grievances appeared to stem from the ubiquitous examples people cited of having themselves been labeled as Nazis – often by Americans or when traveling abroad – or asked demeaning questions like whether they knew Hitler.

What do young people want to see changed about their country’s foreign affairs?

Members of the United Kingdom’s House of Commons sit in session on April 12, 1986. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Although young people were concerned about different aspects of their current foreign policy in each country and group, the solutions they proposed were broadly comparable. In particular, young people highlight the need for greater action on climate change; politicians taking stronger positions, more generally; and more transparency.

More action on climate change is seen as a key policy change for most young adults

Young people see climate change as a global issue requiring global solutions and global solidarity, and especially want their governments to press other countries to comply. As one French woman put it, “even if we make efforts to combat global climate change, compared to the United States, China and Brazil, we are no match.”

“Climate change is very important. All countries in the world must contribute to climate protection because it concerns us all. We need to be more proactive.”

Woman, Germany, left domestically focused

They also seek greater accountability from world leaders, who they sometimes see as more concerned with maintaining the perception of action than real solutions. A UK woman opined, “It seems at these COP things, everyone flies in on their private jet, they say a lot of crap and then there’s not that much action from half the countries.” A man in the same group agreed, “They’re there for the pictures.” A German man even highlighted the hypocrisy of world leaders jetting off to Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, to attend COP27 while implementing low-emissions zones for vehicles in cities across the country.

Young people want politicians to take clearer stands and act more decisively

In Germany, there was a great deal of embarrassment about Germany’s slow response to Ukraine. One man noted: “It took Germany so long” to involve themselves, adding, “I’m sure the people in a French or English focus group would not answer that they were so slow.” Others were embarrassed about how Germany responded – and particularly the decision to send 5,000 helmets, many of which the participants deemed less than adequate. One man jested, “I think it’s good that they’re doing something, but what they’re doing is just embarrassing, supplying cheap helmets … should we send them some damaged tanks too?” (The groups were conducted before the German decision to send Leopard tanks to Ukraine.)

“Being more clear-cut in our choices … being more coherent, as best we can, because I do understand it’s very complicated. But more coherence, a clearer line.”

Woman, France, left internationally engaged

French participants, for their part, often highlight Macron’s trips abroad as lacking subsequent policy action. One French woman observed, “Macron has this position of ‘I have to be present,’” but also offered the caveat that “he doesn’t quite go all the way.” Britons, for their part, largely felt that the UK lacked a foreign policy because of their own domestic turmoil: When asked whether foreign policy was on the right or wrong track, people sarcastically declared that with three prime ministers in as many months, there was no track.

Young people particularly highlighted the ability to act firmly and decisively when it comes to human rights globally. In the U.S., this was of particular concern for internationally engaged Americans who saw protection of human rights globally as an American responsibility. In Germany, one man urged his government to “make a statement when it comes to … the violation of human rights … there need to be clear statements and high ethical and moral standards.”

People on the left and right both focused on the need for new blood in leadership. Participants were concerned that the void of youth in government means their concerns are not adequately addressed. One German man summarized this position: “Politicians are too old … we need younger politicians … because the consequences of current issues will be our problem one day. It is important our generation has a say.”

Young people desire greater transparency in their countries’ global affairs

Some feel distant from their country’s dealings in international organizations. In France, for example, one internationally engaged man noted: “Communication is often on an EU level, and so we don’t have enough visibility on what France brings to this institution.” In a discussion of the UN, one British woman worried that the organization’s decision-making took issues “a bit too far from home,” and that she didn’t have a sense of knowing who was behind decisions.

“A lot of our spending and taxpayer money is spent overseas with very little oversight.”

Man, U.S., right domestically focused

For some, this means clarity from leaders about basic policy actions their government is taking. As one man in the UK put it, this means “transparency as to what we’re actually doing and where it is going and what our goals are.” A French woman concurred, imploring French policymakers to “say clearly what they think, because there’s a gap between their discourse and their acts.” These calls were particularly acute in the right-leaning groups, and among domestically focused participants who see foreign policy as a few steps removed from the democratic process and domestic priorities.

Young people’s calls for transparency also include financial transparency, especially when public funds are involved. Aid to Ukraine amid the Russian invasion was frequently cited as an opportunity for healthy scrutiny, even among those who agreed the benefits of aiding Ukraine was worth the costs. This perceived lack of financial transparency often reinforced domestically focused conservatives’ skepticism of international organizations. A man in the UK likened his government’s financial support of international organizations to a charity pot taxpayers pay into. However, he took issue saying, “You just hear that it’s being used for something good” and that voters are supposed to trust it is being distributed benevolently. In the U.S., one man declared that with “Organizations like NATO and stuff like that … my tendency is to feel like there is a lot of money going into this place. Where is it all going to? And it’s not like anything is happening.”

Young people also want government to be transparent about their foreign policy wins, even saying they should be celebrated more publicly. A German participant claimed, “Many things that are successful … don’t get a lot of publicity,” and further theorized that more exposure of wins could combat skepticism of global institutions and prevent another Brexit-style retreat from global cooperation.

About this essay

This essay was made possible by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. It is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of a number of individuals and experts at Pew Research Center. This cross-national, comparative qualitative research project was designed to explore young adults’ attitudes about foreign policy and how they want their country to engage globally. Analysis is based on the 16 focus groups conducted across France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States in the fall of 2022. Here is more information about the groups and analysis.

Lede photo: (Alain Pitton/NurPhoto via Getty Images)