Ideas from people in 24 countries, in their own words

This Pew Research Center analysis on views of how to improve democracy uses data from nationally representative surveys conducted in 24 countries across North America, Europe, the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific region, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. All responses are weighted to be representative of the adult population in each country.

For non-U.S. data, this analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 27,285 adults conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face with adults in Argentina, Brazil, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Poland and South Africa. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel. Read more about international survey methodology.

In the U.S., we surveyed 3,576 adults from March 20 to March 26, 2023. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way, nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology.

Researchers examined random samples of English responses, machine-translated non-English responses, and non-English responses translated by a professional translation firm to develop a codebook for the main topics mentioned across the 24 countries. The codebook was iteratively improved via practice coding and calculations of intercoder reliability until a final selection of 17 substantive codes was formally adopted. (For more on the codebook, refer to Appendix C.)

To apply the codebook to the full collection of open-ended responses, a team of Pew Research Center coders and professional translators were trained to code English and non-English responses. Coders in both groups coded random samples and were evaluated for consistency and accuracy. They were asked to independently code responses only after reaching an acceptable threshold for intercoder reliability. (For more on the coding methodology, refer to Appendix A.)

There is some variation in whether and how people responded to our open-ended question. In each country surveyed, some respondents said that they did not understand the question, did not know how to answer or did not want to answer. This share of adults ranged from 4% in Spain to 47% in the U.S.

In some countries, people also tended to mention fewer things that would improve democracy in their country relative to people surveyed elsewhere. For example, across the 24 countries surveyed, a median of 73% mentioned only one topic in our codebook (e.g., politicians). The share in South Korea is much higher, with 92% suggesting only one area of improvement when describing what they think would improve democracy. In comparison, about a quarter or more mention two areas of improvement in France, Spain, Sweden and the U.S.

These differences help explain why the share giving a particular answer in certain publics may appear much lower than others, even if it is the top-ranked suggestion for improving democracy. To give a specific example, 10% of respondents in Poland mention politicians, while 18% do so in South Africa – yet the topic is ranked second in Poland and third in South Africa. Given this discrepancy, researchers have chosen to highlight not only the share of the public that mentions a given topic but also its relative ranking among all topics coded, both in text and in graphics.

Here is the question used for this report, along with coded responses for each country, and the survey methodology.

Open-ended responses highlighted in the text of this report were chosen to represent the key themes researchers identified. They have been edited for clarity and, in some cases, translated into English by a professional firm. Some responses have also been shortened for brevity.

Pew Research Center surveys have long found that people in many countries are dissatisfied with their democracy and want major changes to their political systems – and this year is no exception. But high and growing rates of discontent certainly raise the question: What do people think could fix things?

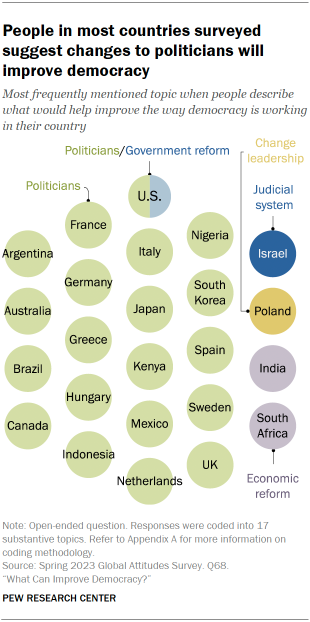

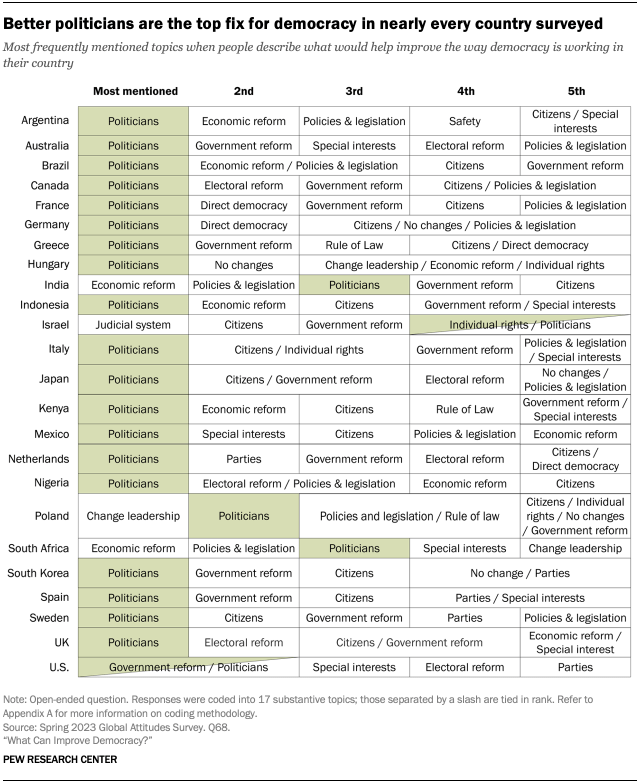

We set out to answer this by asking more than 30,000 respondents in 24 countries an open-ended question: “What do you think would help improve the way democracy in your country is working?” While the second- and third-most mentioned priorities vary greatly, across most countries surveyed, there is one clear top answer: Democracy can be improved with better or different politicians.

People want politicians who are more responsive to their needs and who are more competent and honest, among other factors. People also focus on questions of descriptive representation – the importance of having politicians with certain characteristics such as a specific race, religion or gender.

Respondents also think citizens can improve their own democracy. Across most of the 24 countries surveyed, issues of public participation and of different behavior from the people themselves are a top-five priority.

Other topics that come up regularly include:

- Economic reform, especially reforms that will enhance job creation.

- Government reform, including implementing term limits, adjusting the balance of power between institutions and other factors.

We explore these topics and the others we coded in the following chapters:

- Politicians, changing leadership and political parties (Chapter 1)

- Government reform, special interests and the media (Chapter 2)

- Economic and policy changes (Chapter 3)

- Citizen behavior and individual rights and equality (Chapter 4)

- Electoral reform and direct democracy (Chapter 5)

- Rule of law, safety and the judicial system (Chapter 6)

You can also read people’s answers in their own words in our interactive data essay and quote sorter: “How People in 24 Countries Think Democracy Can Improve.” Many responses in the quote sorter and throughout this report appear in translation; for selected quotes in their original language, visit this spreadsheet.

The survey was conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023, in 24 countries and 36 different languages. Below, we highlight some key themes, drawn from the open-ended responses and the 17 rigorously coded substantive topics.

How politicians can improve

In almost every country surveyed, changes to politicians are the most commonly mentioned way to improve democracy. People broadly call for three types of improvements: better representation, increased competence and a higher level of responsiveness. They also call for politicians to be less corrupt or less influenced by special interests.

Representation

“Bringing in more diverse voices, rather than mostly wealthy White men.”

Woman, 30, Australia

First, people want to see politicians from different groups in society – though which groups people want represented run the gamut. In Japan, for example, one woman said democracy would improve if there were “more diversity and more women parliamentarians.” In Kenya, having leaders “from all tribes” is seen as a way to make democracy work better. People also call for younger voices and politicians from “poor backgrounds,” among other groups. The opposing views of two American respondents, though, highlight why satisfying everyone is difficult:

“Most politicians in office right now are rich, Christian and old. Their overwhelmingly Christian views lead to laws and decisions that not only limit personal freedoms like abortion and gay marriage, but also discriminate against minority religions and their practices.”

– Man, 23, U.S.

“We need to stop worrying about putting people in positions because of their race, ethnicity or gender. What happened to being put in a position because they are the best person for that position?”

– Man, 64, U.S.

Competence

“Our politicians should have an education corresponding to their subject or field.”

Woman, 72, Germany

Second, people want higher-caliber politicians. This includes a desire to see more technical expertise and traits such as morality, honesty, a “stronger backbone” or “more common sense.”

Sometimes, people simply want politicians with “no criminal records” – something mentioned explicitly by a South Korean man and echoed by respondents in the United States, India and Israel, among other places.

Responsiveness

“Make democracy promote more of the people’s voice. The people’s voice is the great strength for leadership.”

Man, 27, Indonesia

Third, people want their politicians to hear them and respond to their needs and wishes, and for politicians to keep their promises. One man in the United Kingdom said, “If leaders would listen more to the local communities and do their jobs as members of Parliament, that would really help democracy in this country. It seems like once they’re elected, they just play lip service to the role.”

Special interests and corruption

Concerns about special interests and corruption are common in certain countries, including Mexico, the U.S. and Australia. One Mexican woman said, “Politicians should listen more to the Mexican people, not buy people off using money or groceries.” Others complained about politicians “pillaging” the country and enriching themselves by keeping tax money.

Calls for systemic reform

For some, the political system itself needs to change in order for democracy to work better. Changing the governmental structure is one of the top five topics coded in most countries surveyed – and it’s tied for the most mentioned issue in the U.S., along with politicians. These reforms include adjusting the balance of power between institutions, implementing term limits, and more.

Some also see the need to reform the electoral system in their country; others want more direct democracy through referenda or public forums. Judicial system reform is a priority for some, especially in Israel. (In Israel, the survey was conducted amid large-scale protests against a proposed law that would limit the power of the Supreme Court, but prior to the Oct. 7 Hamas attack and the court’s rejection of the law in January.)

Government reform

The U.S. stands out as the only country surveyed where reforming the government is the top concern (tied with politicians). Americans mention very specific proposals such as giving the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico statehood, increasing the size of the House of the Representatives to allow one representative per 100,000 people, requiring a supermajority for all spending bills, eliminating the filibuster, and more.

Term limits for elected officials are a particularly popular reform in the U.S. Americans call for them to prevent “career politicians,” as in the case of one woman who said, “I think we need to limit the number of years politicians can serve. No one should be able to serve as a politician for 40+ years like Joe Biden. I don’t have anything against him. I just think that we need limits. We have too many people who have served for too long and have little or nothing to show for it.” Term limits for Supreme Court justices are also top of mind for many Americans when it comes to judicial system reform.

Electoral reform

“There are many parts of the UK where it’s obvious who will get elected. My vote doesn’t count where I live because the Conservative Party wins every time. Effectively it means that the majority is not represented by the government. With proportional representation, everybody’s vote would count.”

Man, 62, UK

The electoral system is among the top targets for change in some countries. In Canada, Nigeria and the UK, changing how elections work is the second-most mentioned topic of the 17 substantive codes – and it falls in the top five in Australia, Japan, the Netherlands and the U.S.

Suggested changes vary across countries and include switching from first-past-the-post to a proportional voting system, having a fixed date for elections, lowering the voting age, returning to hand-counted paper ballots, voting directly for candidates rather than parties, and more.

Direct democracy

Calls for direct democracy are prevalent in several European countries – even ranking second in France and Germany. One French woman said, “There should be more referenda, they should ask the opinion of the people more, and it should be respected.”

In the broadest sense, people want a “direct voting system” or for “people to have the vote, not middlemen elected officials.” More narrowly, they also mention specific topics they would like referenda for, including rejoining the European Union in the UK; “abortion, retirement and euthanasia” in France; “all legislation which harms the justice system” in Israel; asylum policy, nitrogen policy and local affairs in the Netherlands; “when and where the country goes to war” in Australia; “gay marriage, marijuana legalization and bail reform” in the U.S.; “nuclear power, sexuality, NATO and the EU” in Sweden; and who should be prime minister in Japan. (The survey was conducted prior to Sweden joining NATO in March 2024.)

The judicial system

Of the systemic reforms suggested, few bring up changes to the judicial system in most countries. Only in Israel, where the topic ranked first at the time of the survey, does judicial system reform appear in the top 10 coded issues. Israelis approach this issue from vastly different perspectives. For instance, some want to curtail the Supreme Court’s influence over government decisions, while others want to preserve its independence, as in these two examples:

“Finish the legislation that will limit the enormous and generally unreasonable power of the Supreme Court in Israel!”

– Man, 64, Israel

“Do everything to keep the last word of the High Court on any social and moral issue.”

– Man, 31, Israel

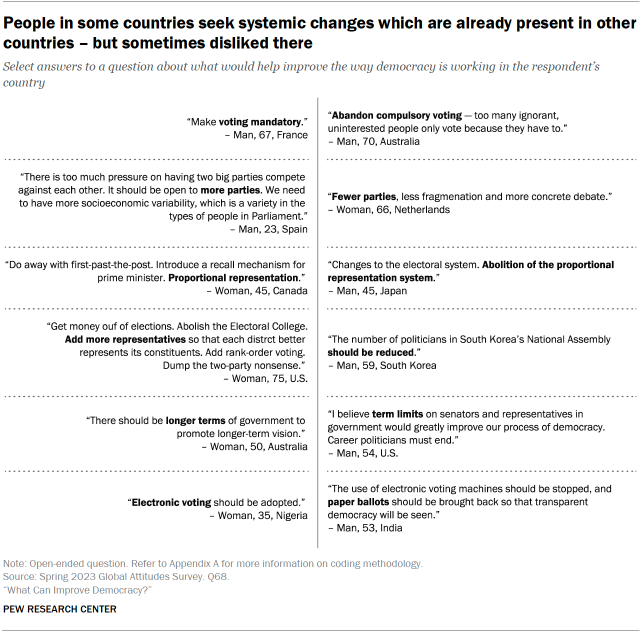

Is the grass always greener?

Notably, some respondents propose the exact reform that those in another country would like to do away with.

For example, while some people in countries without mandatory voting think it could be useful to implement, there are respondents in Australia – where voting is compulsory – who want it to end. People without mandatory voting see it as a way to force everyone to have a say: “We have to get everyone out to vote. Everyone complains. Voting should be mandatory. Everyone has to vote and have a say,” said a Canadian woman. But the flip side one Australian expressed was, “Eliminate compulsory voting. The votes of people who do not care about a result voids the vote of somebody who does.”

The ideal number of parties in government is another topic that brings about opposing suggestions. In the Netherlands, which has a relatively large number of parties, altering the party system is the second-most mentioned way to improve democracy. Dutch respondents differed on terms of the maximum number of parties they want to see (“a three-party system,” “four or five parties at most,” “a maximum of seven parties,” etc.) but the tenor is broadly similar: Too many parties is leading to fragmentation, polarization and division. Elsewhere, however, some squarely attribute polarization to a system with too few parties. In the U.S., a man noted, “The most egregious problem is that a two-party system cannot ever hope to be representative of its people as the will of any group cannot be captured in a binary system: The result will be increased polarization between the Democratic and Republican parties.”

Even in countries with more than two parties, like Canada and the UK, there can be a sense that only two are viable. A Canadian man said, “We need to have a free election with more than two parties.”

For many respondents, fixing democracy begins with the people

Citizens – both their quality and their participation in politics – come up regularly as an area that requires improvement for democracy to work better. In most countries, the issue is in the top five. And in Israel, Sweden, Italy and Japan, citizens are the second-most mentioned topic of the 17 coded. (In this analysis, “citizens” refers to all inhabitants of each country, not just the legal residents.)

In general, respondents see three ways citizens can improve: being more informed, participating more and generally being better people.

Being more informed

“More awareness and more information. We have highly separated classes. There are generations who have never read a newspaper. One cannot be fully democratic if one is not aware.”

Man, 86, Italy

First, citizens being more informed is seen as crucial. Respondents argue that informed citizens are able to vote more responsibly and avoid being misled by surface-level political quips or misinformation.

In the Netherlands, for example, where the survey predated the electoral success of Geert Wilders’ right-wing populist Party for Freedom (PVV), one woman noted that citizens need “education, and openness, maybe. There are a lot of people who vote Geert Wilders because of his one-liners, and they don’t think beyond those. They haven’t learned to think beyond what’s right in front of them.” (For more information on how we classify populist parties, refer to Appendix E.)

Participating more

“Each and every one of us must go to the polls and make our own decisions.”

Woman, 76, Japan

Second, some respondents want people in their country to be more involved in politics – whether that be turning out to vote, protesting at key moments or just caring more about politics or other issues. They hold the notion that if people participate, they will be less apathetic and less likely to complain, and their voices will be represented more fully. One woman in Sweden noted, “I would like to see more involvement from different groups of people: younger people, people with different backgrounds, people from minority groups.”

Being better people

“People should walk around rationally, respecting each other, dialoguing and respecting people’s cultures.”

Woman, 29, Brazil

Third, the character of citizens comes up regularly – respondents’ requests for their countrymen range from “care more about others” to “love God and neighbor completely” to asking that they be “better critical thinkers,” among myriad other things. Still, some calls for improved citizen behavior contradict each other, as in the case of two Australian women who differ over how citizens should think about assimilation:

“We need to be more caring and thoughtful about people who come to the country. We need to be more tolerant and absorb them in our community.”

– Woman, 75, Australia

“We need to stop worrying that we are going to offend other nationalities and their traditions. We should be able to say ‘Merry Christmas’ instead of ‘happy holidays,’ and Christmas celebrations should be held in schools without worrying about offending others in our so-called ‘democratic society.’”

– Woman, 70, Australia

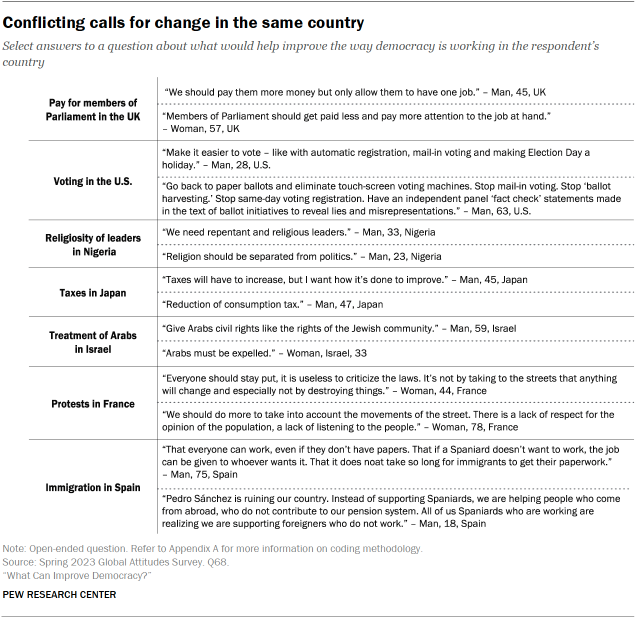

It’s difficult to please everyone

One challenge is that people in the same country may offer the exact opposite solutions. For example, in the UK, some people want politicians to make more money; others, less. In the U.S., while changes to the electoral system rank as one of the public’s top solutions for fixing democracy, some want to make it significantly easier to vote by methods like automatically registering citizens or making it easier to vote by mail. Others want to end these practices or even eliminate touch-screen voting machines.

Economic reform and basic needs

People in several countries, mostly in the middle-income nations surveyed (Argentina, Brazil, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria and South Africa) stand out for the emphasis they place on economic reform as a means to improve democracy. In India and South Africa, for example, the issue ranks first among the 17 substantive topics coded; in Argentina, Brazil, Indonesia and Kenya, it ranks second. These calls include a focus on creating jobs, curbing inflation, changing government spending priorities and more.

“When education, roads, hospitals and adequate water are made available, then I can say democracy will improve.”

Man, 30, Nigeria

Sometimes, people draw a causal link between the economy and democracy, suggesting that improvements to the former would improve the latter. For example, one woman in Indonesia said, “Improve the economic conditions to ensure democracy goes well.” People also insinuated that having basic needs met is a precursor to their democracy functioning. One South African man noted that democracy in his country would work better if the government “created more employment for the youth, fixed the roads and gave us water. They must also fix the electricity problem.” A man in India said, “There’s a need for development in democracy.”

Indeed, specific policies and legislation – particularly improvements to infrastructure like roads, hospitals, water, electricity and schools – are the second-most mentioned topic in Brazil, India, Nigeria and South Africa. Some respondents offer laundry lists of policies that need attention, such as one Brazilian woman who called for “improving health care, controlling drug use, more security for the population, and improving the situation of people on the streets.”

Priority differences in high- and middle-income countries

Beyond economic reform, other changes to living conditions also receive more emphasis in some middle-income countries surveyed:

- In South Africa and Nigeria, both middle-income countries, mentions of economic reform tend to reference jobs. In other, high-income countries, calls for economic change generally refer to other economic issues like inflation and government spending priorities.

- When bringing up the issue of money in politics, respondents in middle-income countries generally cite corruption more than those in high-income countries. Those in high-income countries tend to bring up special interests more broadly.

- People in middle-income countries also focus more on issues related to public safety – including reducing crime and supporting law enforcement – than those in high-income countries.

- For their part, people in the 16 high-income countries surveyed tend to focus more on political party reform, direct democracy, government reform and media reform than those in the eight middle-income nations.

No changes and no solutions – or at least no democratic ones

“Democracy is fine because you have the freedom to express yourself without being persecuted, especially in politics.”

Man, 26, Argentina

People sometimes say there are no changes that can make democracy in their country work better. These responses include broadly positive views of the status quo such as, “I am very happy to live in a country with democracy.” An Indian man responded simply, “Everything is going well in India.” Some respondents even compare their system favorably to others, as one Australian man said: “I think it currently works pretty well, far better than, say, the U.S. or UK, Poland or Israel.”

“Our current system is broken and I’m not sure what, if anything, can fix it at this point.”

Woman, 41, U.S

But some are more pessimistic. They have the sense that “no matter what I do, nothing will change.” A Brazilian man said, “It is difficult to make it better. Brazil is too complicated.”

And some see no better options. In Hungary – where “no changes” was the second-most cited topic of the 17 coded – one man referenced Winston Churchill’s quote about democracy, saying, “Democracy is the worst form of government, not counting all the others that man has tried from time to time.”

No answer

In many countries, a sizable share offer no response at all – saying that they do not know or refusing to answer. This includes around a third or more of those in Indonesia, Japan and the U.S. In most countries, those who did not answer the question tended to have lower levels of formal education than those who offered a substantive solution. And in some places – including the U.S. – they were also more likely to be women than men.

Few call for ending democracy altogether

Despite considerable discontent with democracy, few people suggest changing to a non-democratic system. Those who do call for a new system offer options like a military junta, a theocracy or an autocracy as possible new systems.

Related: Who likes authoritarianism, and how do they want to change their government?

Road map for this research project

One other way to think about what people believe will help improve their democracy is to focus on three themes: basic needs that can be addressed, improvements to the system and complete overhauls of the system. We explore these themes in our interactive data essay and quote sorter: “How People in 24 Countries Think Democracy Can Improve.”

You can also explore people’s responses in their own words, with the option to filter by country and code by navigating over to the quote sorter.

In the chapters that follow, we discuss 15 of our coded themes in detail. We analyze how people spoke about them, as well as how responses varied across and within countries. We chose to emphasize the relative frequency, or rank order, in which people mentioned these different topics. For more about this choice, as well as details about our coding procedure and methodology, refer to Appendix A.

Explore the chapters of this report:

- Politicians, changing leadership and political parties (Chapter 1)

- Government reform, special interests and the media (Chapter 2)

- Economic and policy changes (Chapter 3)

- Citizen behavior and individual rights and equality (Chapter 4)

- Electoral reform and direct democracy (Chapter 5)

- Rule of law, safety and the judicial system (Chapter 6)

Why this report focuses on topic rank order in addition to percentages

There is some variation in whether and how people responded to our open-ended question. In each country surveyed, some respondents said that they did not understand the question, did not know how to answer or did not want to answer. This share of adults ranged from 4% in Spain to 47% in the U.S.

In some countries, people also tended to mention fewer things that would improve democracy in their country relative to people surveyed elsewhere. For example, across the 24 countries surveyed, a median of 73% mentioned only one topic in our codebook (e.g., politicians). The share in South Korea is much higher, with 92% suggesting only one area of improvement when describing what they think would improve democracy. In comparison, about a quarter or more mention two areas of improvement in France, Spain, Sweden and the U.S.

These differences help explain why the share giving a particular answer in certain publics may appear much lower than others, even if the topic is the top mentioned suggestion for improving democracy. To give a specific example, 10% in Poland mention politicians while 18% say the same in South Africa, but the topic is ranked second in Poland and third in South Africa. Given this, researchers have chosen to highlight not only the share of the public who mention a given topic but also its relative ranking among the topics coded, both in the text and in graphics.