This Pew Research Center analysis covers Israeli attitudes toward the country’s leaders, the current and future state of Israeli society, and the influence of various national institutions and groups, all in the context of the Israel-Hamas war.

The data is from a survey of 1,001 Israeli adults conducted face-to-face from March 3 to April 4, 2024. Interviews were conducted in Hebrew and Arabic, and the survey is representative of the adult population ages 18 and older, excluding those in East Jerusalem and non-sanctioned outposts. (The survey also did not cover the West Bank or Gaza.) The survey included an oversample of Arabs in Israel. It was subsequently weighted to be representative of the Israeli adult population with the following variables: gender by ethnicity, age by ethnicity, education, region, urbanicity and probability of selection of respondent.

Prior to 2024, combined totals were based on rounded topline figures. For all reports beginning in 2024, totals are based on unrounded topline figures, so combined totals might be different than in previous years. Refer to the 2024 topline to see our new rounding procedures applied to past years’ data.

Here are the questions used for this report, along with responses, and the survey methodology.

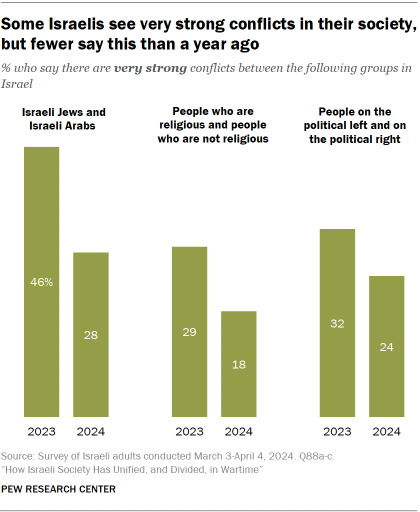

As the Israel-Hamas war rages on, the shares of Israelis who see deep conflicts within their society have lessened over the past year:

- 28% say there are very strong conflicts between Israeli Arabs and Israeli Jews, down from 46% in 2023.

- 18% say there are very strong conflicts between people who are religious and people who are not, down from 29%.

- 24% see very strong conflicts between those on the political left and right, down from 32% last year. (Read more about conflicts in Israeli society in Chapter 1.)

Research in the West Bank and Gaza

Pew Research Center has polled the Palestinian territories in previous years, but in our 2024 survey, we were unable to survey in Gaza or the West Bank due to security concerns. We are actively investigating possible ways to conduct both qualitative and quantitative research on public opinion in the region and will provide more data as soon as we are able.

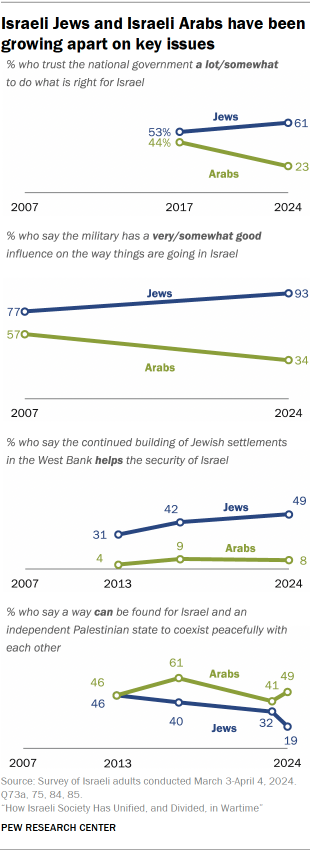

At the same time, Israeli public opinion has become more polarized in other ways. For example, Arab Israelis and Jewish Israelis have increasingly diverging views on key institutions – such as the military – and on policy issues:

- Jewish Israelis trust the national government to do what is right for Israel more than they did in 2017 (61%, up from 53%). Arab Israelis trust it less (23%, down from 44%).

- 93% of Jewish Israelis think the military has a positive influence on the way things are going in Israel, while just 34% of Arab Israelis agree. This gap has grown significantly since we last asked the question in 2007, when 77% of Israeli Jews and 57% of Israeli Arabs said the military’s influence was positive. (Read more about confidence in the government and institutions in Chapter 2.)

- Israelis as a whole are still divided over whether the building of Jewish settlements in the West Bank helps (40%) or hurts (35%) Israel’s security. But Jewish Israelis have grown more likely to see the settlements as helping security, widening the ethnic gap on this question. (Read more about views of settlements in Chapter 3.)

- Fewer Israelis think a way can be found for Israel and an independent Palestinian state to coexist peacefully than said the same last year (26%, down from 35%). Most of the decline comes from shifting opinions among Jewish Israelis. (Read more about views of a two-state solution in our previous report.)

Views among those on the ideological left and right have also diverged on some of these key issues since we last asked about them. For example, 19% of those who place themselves on the left trust the national government, compared with 75% of those on the right – a difference of 56 percentage points. In 2017, the difference was 43 points (26% on the left trusted the government, compared with 69% of those on the right).

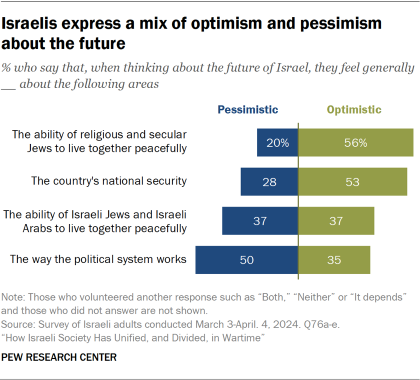

Against this backdrop, Israelis are more pessimistic (50%) than optimistic (35%) about the way their political system works. And, whereas Arabs and Jews were about equally pessimistic about the political system in 2019, Arabs have become more pessimistic (69%, up from 57%) while Jews have become less so (44%, down from 55%).

Israelis are also divided on the prospect of Arab and Jewish Israelis living together peacefully, with equal shares saying they are optimistic (37%) and pessimistic (37%) about this. About a quarter (23%) said they are both, neither or that it depends.

Still, Israelis are more optimistic than pessimistic about the country’s national security and the ability of religious and secular Jews to live together peacefully.

Related: Israeli Views of the Israel-Hamas War

These are among the key findings of a survey of 1,001 Israelis, conducted via face-to-face interviews from March 3 to April 4, 2024.

Views of political leaders

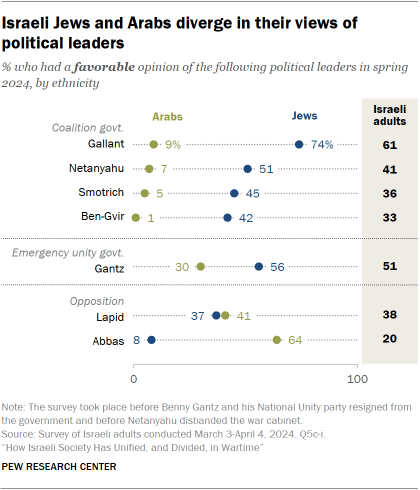

In March and early April, attitudes toward Israel’s political leadership were largely negative. (The survey took place before war cabinet member Benny Gantz resigned from the government and before Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu disbanded the emergency war cabinet.)

At the time of the survey, just one of the seven officials we asked about – Defense Minister Yoav Gallant – received favorable ratings from a clear majority of Israelis.

Jewish and Arab Israelis had very different views of the six other Israeli politicians we asked about. The largest gaps were in evaluations of Gallant (Jews were 65 percentage points more favorable than Arabs); Mansour Abbas, the leader of the United Arab List, which is better known in Israel as Ra’am (-56); and Netanyahu (+44). Only Israeli opposition leader Yair Lapid was seen about equally favorably by Jews and Arabs (37% vs. 41%).

Ideological divides between the right and left were also large – particularly when it came to Netanyahu (those on the right were 61 points more favorable than those on the left), Ben-Gvir (+54) and Smotrich (+54).

(Read more about views of Israeli leaders in Chapter 1, and explore views of Palestinian leaders in our previous report.)

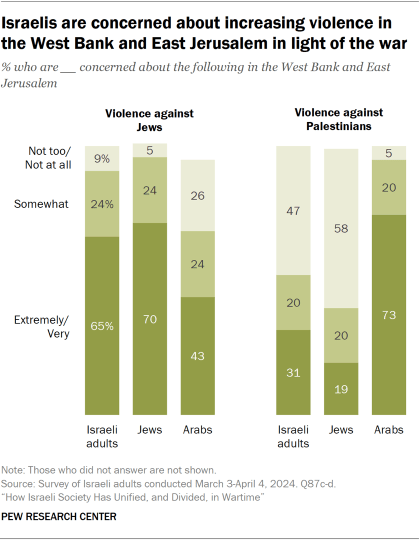

Violence in the West Bank and East Jerusalem

Around two-thirds of Israelis say they are extremely or very concerned about violence against Jews in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. Around a third are similarly concerned about violence against Palestinians. But concerns differ dramatically by ethnicity:

- Jewish Israelis (70%) are more concerned than Arab Israelis (43%) about rising violence against Jews in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

- Arab Israelis (73%) are much more concerned than Jewish Israelis (19%) about violence against Palestinians in East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

There are also ideological differences, with left-leaning Israelis expressing much more concern than right-leaning Israelis about violence against Palestinians and much less concern about violence against Jews.

Jewish religious groups in Israel: Haredim, Datiim, Masortim and Hilonim

Nearly all Israeli Jews identify as Haredi (commonly translated as “ultra-Orthodox”), Dati (“religious”), Masorti (“traditional”) or Hiloni (“secular”). The spectrum of religious observance in Israel – on which Haredim are generally the most religious and Hilonim the least – does not always line up perfectly with Israel’s political spectrum. On some issues, including those pertaining to religion in public life, there is a clear overlap: Haredim are furthest to the right, and Hilonim are furthest to the left, with Datiim and Masortim in between. But on other political issues, including those related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and views of the United States, differences between religious groups do not always mirror those between people at different points on the ideological spectrum. Because of sample size considerations, we combine Haredim and Datiim for analysis in this report.

For more information on the different views of these religious groups, read the Center’s 2016 deep dive on the topic, “Israel’s Religiously Divided Society.”

CORRECTION (August 8, 2024): This report, including graphics, has been updated to reflect that a survey question asked about violence against Palestinians in the West Bank and East Jerusalem, not violence against Arabs (as was previously reported). Also, a question about the ability of religious and secular people to live together peacefully asked about religious and secular Jews, not Israelis.