Global Elections in 2024: What We Learned in a Year of Political Disruption

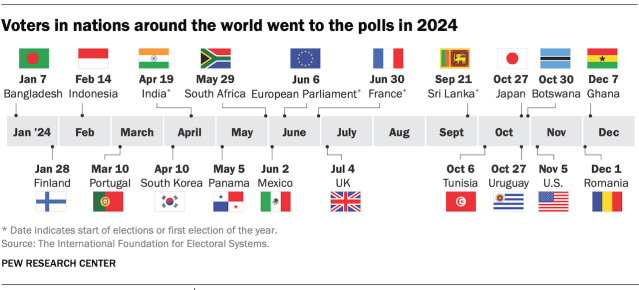

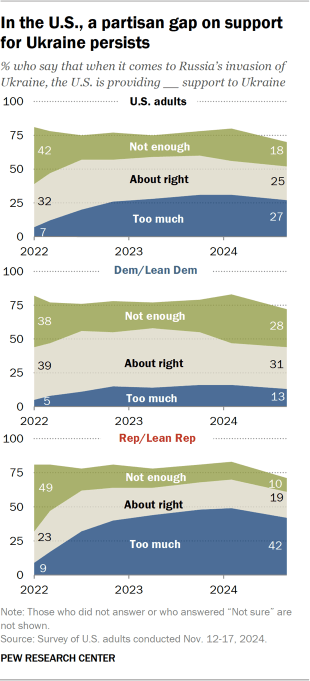

2024 was a remarkable year for elections as voters in more than 60 countries went to the polls. It also turned out to be a difficult year for incumbents and traditional political parties. Rattled by rising prices, divided over cultural issues and angry at the political status quo, voters in many countries sent a message of frustration.

This analysis of the 2024 election year is based on global public opinion data from surveys conducted by Pew Research Center and independent research. Links to original sources of data – including the methodologies of individual surveys and the specific questions asked – are available here:

- Global ratings of the economy and democracy in 2024.

- International attitudes toward tradition and change in 2022.

- Americans’ views of U.S. support for Ukraine in 2024.

In this essay, we analyze four major themes that emerged from this year’s busy slate of elections around the world:

- A tough year for incumbents

- The staying power of right-wing populism

- Polarized battles over tradition and change

- International conflicts with political implications

A tough year for incumbents

South Africa’s general election results come in at the Gallagher Convention Center in Midrand on June 2, 2024. The African National Congress failed to win a majority of National Assembly seats for the first time since the end of apartheid. (Phill Magakoe/AFP via Getty Images)

In one of the year’s highest-profile elections, Democrats in the United States lost the presidency, with Donald Trump, the Republican former president, defeating Vice President Kamala Harris. Republicans also won majorities in both houses of Congress.

It was the third straight U.S. presidential election in which the incumbent party lost. And it was one of many notable losses for incumbents around the world in 2024:

- In the United Kingdom – unlike in the U.S. – political power swung to the left. The Labour Party won an overwhelming parliamentary majority, bringing 14 years of Conservative Party rule to an end.

- The most dramatic defeat for a longtime incumbent party may have occurred in the southern African nation of Botswana, where the Botswana Democratic Party lost power for the first time in nearly 60 years.

- In April, South Korean voters gave the opposition Democratic Party a majority of seats in the National Assembly in what was seen as a check on President Yoon Suk Yeol of the People Power Party. In early December, President Yoon imposed martial law and accused Democratic Party leaders of “anti-state” activities. The National Assembly quickly reversed Yoon’s decision, voting unanimously to lift martial law.

- Opposition parties of various ideological stripes won power in a diverse set of nations, including Ghana, Panama, Portugal and Uruguay.

Elsewhere, incumbent parties held on to power but still suffered significant setbacks:

- In South Africa, the African National Congress failed to win a majority of National Assembly seats for the first time since the end of apartheid.

- Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party – which has governed the country for most of the post-World War II era – and its coalition partner, Komeito, lost their majority in the parliament.

- India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his Bharatiya Janata Party won a third consecutive victory but were forced into a coalition government.

- In France, President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to hold snap elections in the summer backfired. Macron’s centrist Ensemble alliance lost ground to both the left-wing New Popular Front and the right-wing National Rally.

What made 2024 such a tough year for incumbents? While every election is shaped by local factors, economic challenges were a consistent theme across the globe. That included the U.S., where the economy was the top issue for registered voters – especially for those who supported Trump.

A survey we conducted in 34 countries earlier this year illustrated the extent of global economic gloom. Across these nations, a median of 64% of adults said their national economy was in bad shape. In several nations that held elections in 2024 – including France, Japan, South Africa, South Korea and the UK – more than seven-in-ten expressed this view.

Inflation was an especially important issue in this year’s elections, although economic concerns were prevalent in many countries before the post-pandemic wave of global price increases. The past two decades have seen financial crises, the Great Recession, the COVID-19 economic downturn, inflation and ongoing economic inequality, all of which may have shaped the mood in nations around the globe.

But the economy wasn’t the only thing driving voter discontent. Our global surveys over the past few years have highlighted a broader frustration with the functioning of representative democracy. Across 31 nations we surveyed in 2024, a median of 54% of adults were dissatisfied with the way democracy is working in their country. And in several high-income nations, dissatisfaction has increased significantly over the past three years.

Our surveys have shown that many people feel disconnected from political leaders and institutions. Large majorities in many nations believe elected officials don’t care what people like them think. Many say there is no political party that represents their views well. And large shares say people like them have little or no influence on politics in their country.

The staying power of right-wing populism

Supporters of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party gather at a campaign rally in Erfurt, Germany, on Aug. 31, 2024. AfD went on to win in Thuringia, becoming Germany’s first far-right party to win a state election since World War II. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Frustrations with the political class have created opportunities for right-wing populists and other challengers to traditional parties and the political status quo. Several elections this year in Europe highlighted this trend:

- Right-wing populist parties, many of which campaigned on sharply anti-immigration platforms, gained ground in this year’s European parliamentary elections.

- Parties on the left and in the center worked together to keep Marine Le Pen’s right-wing populist National Rally out of power in France in this year’s parliamentary elections. But Le Pen’s party nonetheless significantly increased the number of seats it holds in the National Assembly. In early December, National Rally voted with New Popular Front, a coalition of left-leaning parties, to end the government of conservative Michel Barnier after just three months.

- In Austria, the far-right Freedom Party won 29% of the vote in September elections – a higher share than any other party and its best-ever result. It is unlikely, however, that any governing coalition will include the party.

- Three far-right parties had a strong showing in Romania’s Dec. 1 parliamentary elections. Also, right-wing candidate Calin Georgescu received the most votes in the first round of the country’s presidential elections. However, on Dec. 6, Romania’s Constitutional Court annulled the first-round results after evidence emerged of substantial Russian interference in the election.

- Portugal joined the list of European nations with a significant right-wing party following Chega’s success in the March elections. The party won 50 out of 230 parliamentary seats, up from just 12 in 2022 and one in 2019.

- Reform UK won the third-highest share of the vote in the United Kingdom’s general election, with 14%. And its leader, Nigel Farage, finally won a seat in Parliament in his eighth attempt.

- Alternative for Germany became the first far-right political party to win a state election in Germany since World War II.

Over the past decade, commentators have regularly debated whether right-wing populism in Europe is rising or falling, based on the results of the most recent election. But the larger story is that right-wing populist parties have become embedded in Europe’s political landscape, significantly disrupting the continent’s politics.

In some cases, right-wing parties have won the most votes, as in the Netherlands in 2023 and Italy in 2022. Sometimes they have lost power, as in Poland’s late 2023 elections. But they are now consistently competitive in ways they were not until relatively recently.

Populists have had success outside of Europe as well. In the United States, Trump’s “Make America Great Again” movement has become the dominant force within the Republican Party. The party has moved in a populist direction that looks very different from the pre-2015 GOP.

With Republican electoral victories this year, the party will soon control the executive and legislative branches of government. Republican presidents have also appointed six of the nine current Supreme Court justices. Trump appointed three of these in his first term and may have the opportunity to appoint more in his second.

Different varieties of right-wing leaders have found success in other regions as well. In India, Narendra Modi may have suffered a setback in this year’s elections, but he still dominates the nation’s politics. In Indonesia, Prabowo Subianto won the presidential election amid concerns about his human rights record.

Right-wing leaders in Latin America offer an eclectic mix of ideologies. But as The Economist has noted, several share an opposition to abortion, women’s rights and LGBTQ+ rights; an opposition to social democracy; and a hard-line view on crime. This group includes Javier Milei, who won the presidential election in Argentina in December 2023, and El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, who won reelection as president with over 80% of the vote and was buoyed by strong support for his crackdown on criminal gangs.

Populism has had some success on the left, too. One example is Mexico’s Morena party, which has only been in existence for about a decade but now dominates the nation’s politics. Building on the popularity of outgoing President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and the country’s relatively positive economic mood, Morena won outright majorities in both chambers of the Congress. And Morena’s Claudia Sheinbaum is now Mexico’s first female president.

Whether on the right or left, populist parties have been able to capitalize on voters’ frustrations with elites – and the belief, shared by many, that establishment parties and leaders are out of touch with ordinary citizens.

Polarized battles over tradition and change

Abortion-rights supporters stage a counterprotest during the 50th annual March for Life rally on Washington, D.C.’s National Mall on Jan. 20, 2023, several months after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling ended the federal right to abortion. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

The spread of populism has coincided with deepening political divides over culture and identity in many nations.

In France, Le Pen and her National Rally party regularly make arguments about defending French culture and civilization from immigrants and outsiders. The Freedom Party of Austria, Alternative for Germany, the Party for Freedom in the Netherlands and the Brothers of Italy also have made concerns about immigration – especially immigration from predominantly Muslim nations – central to their platforms.

Additionally, Austria’s Freedom Party has opposed LGBTQ+ rights. Its platform includes a constitutional determination that there are only two genders, and the party opposes same-sex relationships. Similar issues have appeared in other 2024 elections as well.

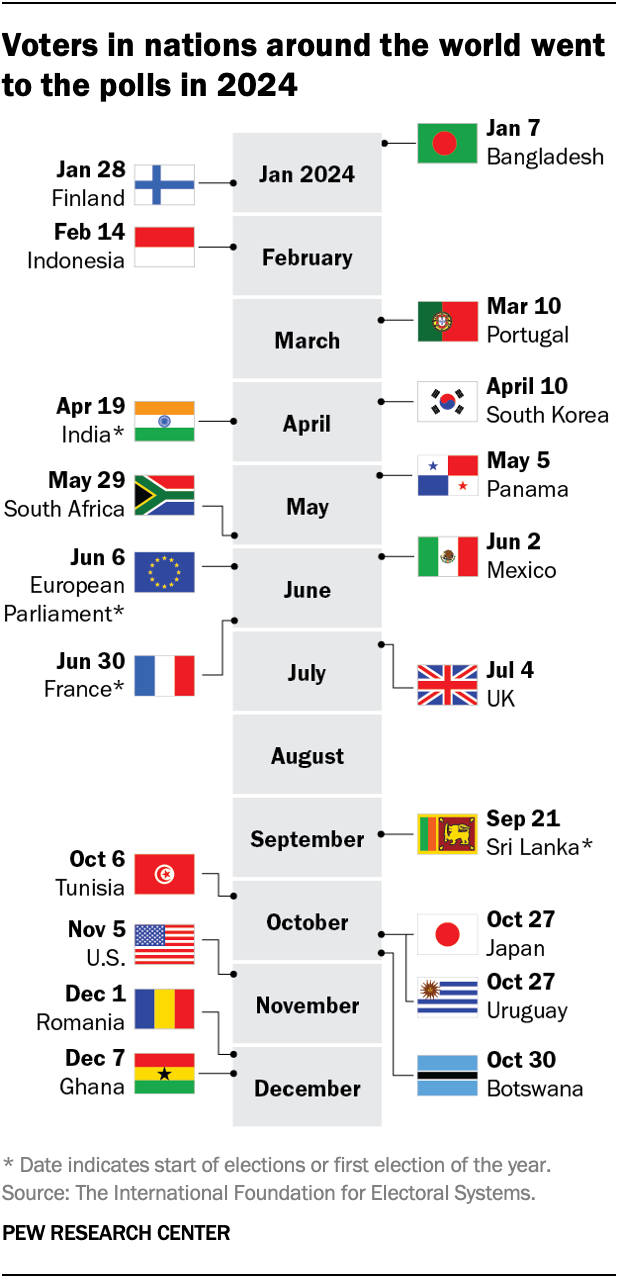

More broadly, surveys have found sharp ideological divides over the value of tradition in society.

A 2022 cross-national Pew Research Center survey included a question exploring tradition and change. It asked respondents whether they believe their country will be better off in the future if it sticks to its traditions and ways of life, or if it is open to changes regarding its traditions and ways of life.

In 15 of the 16 nations where we measured ideology, there was a significant difference between the ideological right and left. The gap was largest by far in the United States, where 91% of liberals say the country will be better off if it embraces change, compared with just 28% of conservatives.

And our cross-national polling has consistently shown that the U.S. is more ideologically divided than most, with especially wide gaps on issues including abortion and climate change.

America’s two-party system has a tendency to exacerbate ideological differences. And as Ezra Klein, Lilliana Mason and other writers have described, polarization has intensified in recent years as various types of identities have become “stacked” on top of people’s partisan identities. Today, race, religion and ideology are often more aligned with partisanship than was the case when the two major parties were relatively heterogenous coalitions. Often, this results in identity-based conflicts and seemingly existential arguments over different conceptions of American identity.

International conflicts with political implications

A Ukrainian gunner stands guard in an infantry fighting vehicle on Dec. 7, 2023, in the Donetsk province of Ukraine. (Roman Chop/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)

Voters almost always prioritize domestic issues over international challenges. But international conflicts – especially the Russia-Ukraine and Israel-Hamas wars – nonetheless played an important role in the global election year of 2024.

In many nations, there are ideological divisions over how to deal with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, with support for Kyiv often lower among those on the ideological right.

Just days before elections in the United Kingdom, Farage, the leader of the Reform UK party, reiterated previous claims that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had been “provoked” by “the ever-eastward expansion of NATO and the European Union.” In France, Le Pen has been critical of EU sanctions against Russia and has called for restrictions on French aid to Ukraine. And she has had kind words in the past for Russian President Vladimir Putin and his policies.

In Slovakia, voters chose as their new president Peter Pellegrini, a close ally of the country’s pro-Russia Prime Minister Robert Fico. And right-wing populist parties in Austria and Germany have expressed reservations about support for Ukraine.

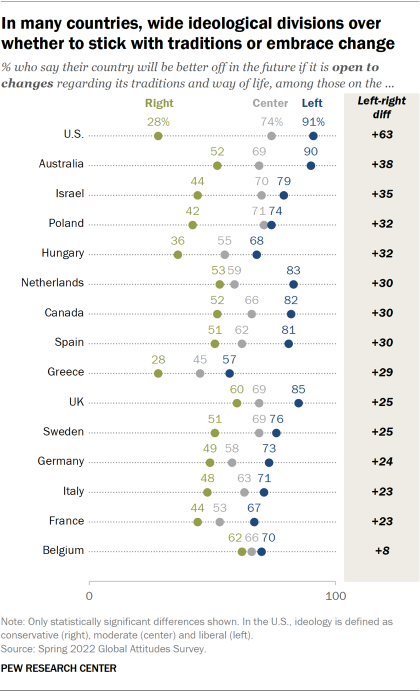

Many on the ideological right in the United States are also skeptical about supporting Ukraine. When a Ukraine aid bill passed the House of Representatives in April, Republicans were divided, with 101 voting in favor and 112 opposing the legislation.

At the Munich Security Conference in February, JD Vance – now the vice president-elect – said the U.S. should provide less aid to Kyiv. And as a Senate candidate in 2022, he said, “I don’t really care what happens to Ukraine one way or another.”

Pew Research Center polling has documented declining support among Republicans for providing aid to Ukraine since Russia’s invasion.

Meanwhile, the Israel-Hamas war has generated tensions within the ideological left.

Take the United Kingdom. While the Labour Party won an overwhelming victory this year, some of its few losses were to candidates on the left who were critical of Prime Minister Keir Starmer’s support for Israel.

In the United States, polling highlights sharp divisions among the supporters of the Democratic Party, especially young liberals, many of whom opposed the Biden administration’s approach to the Israel-Hamas war. It was also an issue in France, where many have accused leaders of France Unbowed – which has been strongly critical of Israel – of antisemitism.

Looking ahead

The list of nations set to hold national elections in 2025 includes Canada, Chile, Germany, Jamaica, Norway and Singapore. The results will show whether incumbents – and those who are seen as representing the political status quo – continue to be targets of voter discontent.

Acknowledgments

This report was written by Richard Wike, director of global attitudes research; Moira Fagan, research associate; and Laura Clancy, research analyst. Janakee Chavda, associate digital producer, produced the report. John Carlo Mandapat, information graphics designer, produced the graphics. It was checked by Christine Huang, research associate; and Jordan Lippert, research analyst. David Kent, senior copy editor, copy edited it. Editorial guidance was provided by John Gramlich, associate director of short reads.

Photo credits

South Africa’s general election results come in at the Gallagher Convention Center in Midrand on June 2, 2024. The African National Congress failed to win a majority of National Assembly seats for the first time since the end of apartheid. (Phill Magakoe/AFP via Getty Images)

Supporters of the Alternative for Germany (AfD) political party gather at a campaign rally in Erfurt, Germany, on Aug. 31, 2024. AfD went on to win in Thuringia, becoming Germany’s first far-right party to win a state election since World War II. (Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

Abortion-rights supporters stage a counterprotest during the 50th annual March for Life rally on Washington, D.C.’s National Mall on Jan. 20, 2023, several months after a U.S. Supreme Court ruling ended the federal right to abortion. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

A Ukrainian gunner stands guard in an infantry fighting vehicle on Dec. 7, 2023, in the Donetsk province of Ukraine. (Roman Chop/Global Images Ukraine via Getty Images)