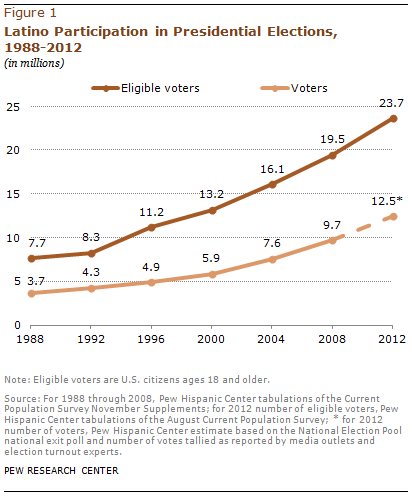

The record number1 of Latinos who cast ballots for president this year are the leading edge of an ascendant ethnic voting bloc that is likely to double in size within a generation, according to a Pew Hispanic Center analysis based on U.S. Census Bureau data, Election Day exit polls and a new nationwide survey of Hispanic immigrants.

The nation’s 53 million Hispanics comprise 17% of the total U.S. population but just 10% of all voters this year, according to the national exit poll. To borrow a boxing metaphor, they still “punch below their weight.”

However, their share of the electorate will rise quickly for several reasons. The most important is that Hispanics are by far the nation’s youngest ethnic group. Their median age is 27 years—and just 18 years among native-born Hispanics—compared with 42 years for that of white non-Hispanics. In the coming decades, their share of the age-eligible electorate will rise markedly through generational replacement alone.

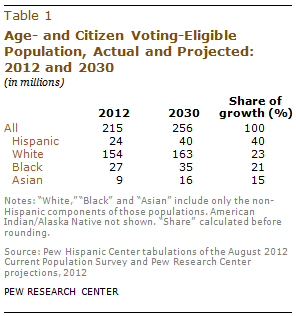

According to Pew Hispanic Center projections, Hispanics will account for 40% of the growth in the eligible electorate in the U.S. between now and 2030, at which time 40 million Hispanics will be eligible to vote, up from 23.7 million now.2

Moreover, if Hispanics’ relatively low voter participation rates and naturalization rates were to increase to the levels of other groups, the number of votes that Hispanics actually cast in future elections could double within two decades.

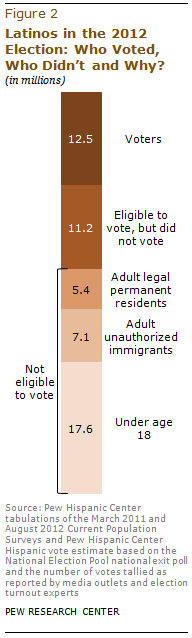

If the national exit poll’s estimate proves correct that 10% of all voters this year were Hispanic, it would mean that as many as 12.5 million Hispanics cast ballots. But perhaps a more illuminating way to analyze the distinctive characteristics of the Hispanic electorate—current and future—is to parse the more than 40 million Hispanics in the United States who did not vote or were not eligible to vote in 2012. That universe can be broken down as follows:

- 11.2 million are adults who were eligible to vote but chose not to. The estimated 44% to 53% turnout rate of eligible Hispanic voters in 2012 is in the same range as the 50% who turned out in 2008. But it still likely lags well below the turnout rate of whites and blacks this year.3

- 5.4 million are adult legal permanent residents (LPRs) who could not vote because they have not yet become naturalized U.S. citizens. The naturalization rate among legal immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean trails that of other legal immigrants by a sizable margin—49% versus 72%, according to a Pew Hispanic analysis of the 2011 March Current Population Survey (CPS). The new Pew Hispanic survey finds that a major reason Hispanic immigrants naturalize is to gain civil and legal rights, including the right to vote. The flexing of electoral muscle by Hispanic voters this year conceivably could encourage more legal immigrants to become naturalized citizens.

- 7.1 million are adult unauthorized immigrants and would become eligible to vote only if Congress were to pass a law creating a pathway to citizenship for them. Judging by the immediate post-election comments of leading Democratic and Republican lawmakers, the long-dormant prospects for passage of such legislation appear to have been revived by Latinos’ strong showing at the polls.

- 17.6 million are under the age of 18 and thus too young to vote—for now. That vast majority (93%) of Latino youths are U.S-born citizens and thus will automatically become eligible to vote once they turn 18. Today, some 800,000 Latinos turn 18 each year; by 2030, this number could grow to 1 million per year, adding a potential electorate of more than 16 million new Latino voters to the rolls by 2030.

Thus, generational replacement alone will push the age- and citizen-eligible Latino electorate to about 40 million within two decades. If the turnout rate of this electorate over time converges with that of whites and blacks in recent elections (66% and 65%, respectively, in 2008), that would mean twice as many Latino voters could be casting ballots in 2032 as did in 2012.

This turnout could rise even more if naturalization rates among the 5.4 million adult Hispanic legal permanent residents were to increase over time—and/or if Congress were to pass a comprehensive immigration reform bill that creates a pathway to citizenship for the more than 7 million unauthorized Hispanic immigrants already living in the U.S.

The Pew Hispanic Center survey finds that more than nine-in-ten (93%) Hispanic immigrants who have not yet naturalized say they would if they could. Of those who haven’t, many cite administrative costs and barriers, a lack of English proficiency and a lack of initiative. For example, according to the survey, only 30% of Hispanic immigrants who are LPRs say they speak English “pretty well” or “very well.”

In addition to all these factors, there is the as-yet-unknowable size and impact of future immigration. About 24 million Hispanic immigrants have come to U.S. in the past four decades—in absolute numbers, the largest concentrated wave of arrivals among any ethnic or racial group in U.S. history. Some 45% arrived in the U.S. legally, and 55% arrived illegally.4

Assuming Hispanic immigration continues into the future —even at the significantly reduced levels of recent years—the Hispanic electorate will expand beyond the numbers dictated by the growth among Hispanics already living in the U.S. And because immigrants tend to have more children than the native born, the demographic ripple effect of future immigration on the makeup of the electorate will be felt for generations.

In 2008, the Pew Research Center projected that the Hispanic share of the total U.S. population would be 29% by 2050 (Passel and Cohn, 2008). Since that projection was made, the annual level of Hispanic immigration has declined sharply (Passel, Cohn and Gonzalez-Barrera, 2012). Because of this decline, the share of Hispanics in 2050 now appears unlikely to reach 29%. However, the 2008 projection also included a “low immigration scenario” that showed the Hispanic share of the U.S. population would be 26% by mid-century (Passel and Cohn, 2008)—still much higher than today’s 17%.

Who Naturalizes and Who Doesn’t

A record 15.5 million legal immigrants were naturalized U.S. citizens in 2011, according to a Pew Hispanic Center analysis of Census Bureau data. In addition, the share of the nation’s legal immigrants who have become U.S. citizens has reached its highest level in three decades—56%. However, naturalization rates among legal immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean (49%), especially Mexican legal immigrants (36%), remain below those of other immigrants (72%).

In the new Pew Hispanic Center survey, when asked in an open-ended question why they decided to naturalize, almost one-in-five (18%) naturalized Hispanic immigrants said that acquiring civil and legal rights—including the right to vote—was the main reason. This response was closely followed by an interest in having access to the benefits and opportunities derived from U.S. citizenship (16%) and family-related reasons (15%). Other reasons included viewing the U.S. as home (12%) and wanting to become American (6%).

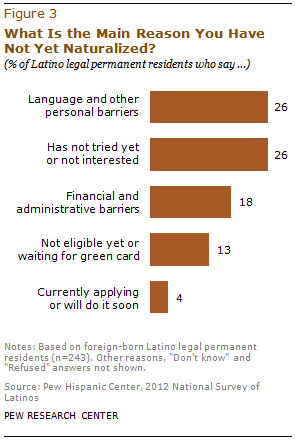

The Pew Hispanic survey also explored the reasons Hispanic immigrants who are legal permanent residents haven’t yet tried to become citizens. According to the survey, when asked in an open-ended question why they had not naturalized thus far, 45% identified either personal barriers (26%), such as a lack of English proficiency, or administrative barriers (18%), such as the financial cost of naturalization.

About this Report

This report explores the growing size of the Hispanic electorate and the reasons Hispanic immigrants give for naturalizing to become a U.S. citizen—and for not naturalizing.

The report uses several data sources. Latino vote shares are based on the National Election Pool national exit poll as reported on November 6, 2012, by CNN’s Election 2012 website. Data on Latino immigrants’ views of naturalization are based on the Pew Hispanic Center’s 2012 National Survey of Latinos (NSL). The NSL survey was conducted from September 7 through October 4, 2012, in all 50 states and the District of Columbia among a randomly selected, nationally representative sample of 1,765 Latino adults, 899 of whom were foreign born. The survey was conducted in both English and Spanish on cellular as well as landline telephones. The margin of error for the full sample is plus or minus 3.2 percentage points. The margin of error for the foreign-born sample is plus or minus 4.4 percentage points. Interviews were conducted for the Pew Hispanic Center by Social Science Research Solutions (SSRS).

For data on the legal status of immigrants, Pew Hispanic Center estimates use data mainly from the Current Population Survey (CPS), a monthly survey of about 55,000 households conducted jointly by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Census Bureau. It is best known as the source for monthly unemployment statistics. Each March, the CPS sample size and questionnaire are expanded to produce additional data on the foreign-born population and other topics. The Pew Hispanic Center estimates make adjustments to the government data to compensate for undercounting of some groups, and therefore its population totals differ somewhat from the ones the government uses. Estimates of the number of immigrants by legal status for any given year are based on a March reference date. For more details, see Passel and Cohn (2010).

This report was written by Director Paul Taylor, Research Associate Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, Senior Demographer Jeffrey S. Passel and Associate Director Mark Hugo Lopez. Ana Gonzalez-Barrera took the lead in developing the survey questionnaire’s naturalization section. Passel and D’Vera Cohn provided comments on earlier drafts of the report. The authors also thank Scott Keeter, Leah Christian, Cohn, Richard Fry, Cary Funk, Rakesh Kochhar, Rich Morin, Seth Motel, Kim Parker, Passel, Eileen Patten and Antonio Rodriguez for guidance on the development of the survey instrument. Motel provided excellent research assistance. Fry, Morin and Patten number-checked the report text and topline. Marcia Kramer was the copy editor.

A Note on Terminology

The terms “Latino” and “Hispanic” are used interchangeably in this report.

“Foreign born” refers to persons born outside of the United States, Puerto Rico or other U.S. territories to parents neither of whom was a U.S. citizen.

The following terms are used to describe immigrants and their status in the U.S. In some cases, they differ from official government definitions because of limitations in the available survey data.

Legal permanent resident, legal permanent resident alien, legal immigrant, authorized migrant: A citizen of another country who has been granted a visa that allows work and permanent residence in the U.S. For the analyses in this report, legal permanent residents include persons admitted as refugees or granted asylum.

Naturalized citizen: Legal permanent resident who has fulfilled the length of stay and other requirements to become a U.S. citizen and who has taken the oath of citizenship.

Unauthorized migrant: Citizen of another country who lives in the U.S. without a currently valid visa.

Eligible immigrant: In this report, a legal permanent resident who meets the length of stay qualifications to file a petition to become a citizen but has not yet naturalized.

Legal temporary migrant: A citizen of another country who has been granted a temporary visa that may or may not allow work and temporary residence in the U.S.