Getting information means getting help for the big and small challenges people encounter.

On the face of things, getting one’s car repaired appears as easy as opening the phone book and looking for a mechanic. Finding a job might seem as straightforward as looking at the want ads, going to a job fair, or to an employment counselor. Addressing a health care issue is more involved, with the level of complexity depending on the problem, who is affected, the insurance status of the person with a problem, and the amount of support from family and friends.

It doesn’t take long to realize that getting help often begins with getting information. Which auto mechanic is reliable and fair? Not every job opening might appear in the newspaper or online listings, and a certain employment counselor might not be appropriate for a specific person’s skills or needs. For problems such as health care, it is hard to separate gathering information from the act of getting help.

People use their social networks to seek information and advice.

This is where people often come into play in the process of finding the necessary information to chart the right course for getting help. A close friend or family member may know an auto mechanic who specializes in the make of your car. A work colleague — or maybe an acquaintance of that colleague — may know a good place for adult day care for an elderly relative in need.

Network capital refers to the personal ties people may draw upon as a source of trusted information when people have to deal with the institutions and rules which are usually part of problem-solving.

In these examples, one’s personal network is the avenue for help. People you know — sometimes very well, but often not — are the conduits for getting information that adds to your ability to address a problem. They constitute network capital — personal ties that are a source of trusted information that help people negotiate through the thicket of institutions and rules that are unavoidable parts of dealing with problems.

A key question in this research is whether people’s networks affect their capacity to address various problems in their lives, with a special focus on whether the internet and other communication technologies leverage people’s social networks. Although the size of people’s social networks and their structures (lots of significant ties or active membership in community groups) may provide access to resources that offer help, it may be that information technologies make these networks more effective.

To get at these issues, the Social Ties survey asked respondents whether they had gotten help from people in their social networks for any of the following eight issues:

- Finding a new place to live

- Changing jobs

- Buying a personal computer

- Making a major investment or financial decision

- Looking for information about a major illness or medical condition

- Caring for someone with a major illness or medical condition

- Putting up drywall in your house

- Deciding who to vote for in an election

The list was designed to probe issues of great importance, such as health care, things that involve spending money, such as buying a computer, and issues that pertain to decision-making, such as voting or investing.

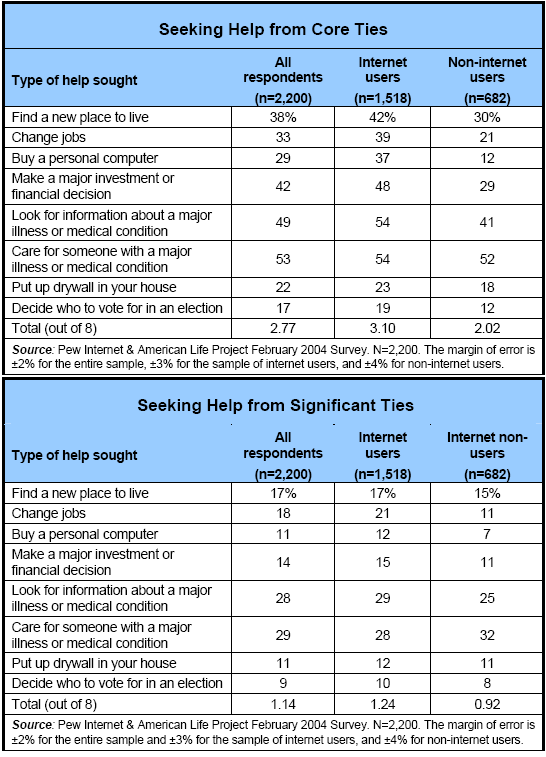

As the following tables show, people are generally more likely to turn for help to their core ties than to their significant ties. The tables also show that internet users tend to reach into their social networks for help more often than non-users. A fairly consistent pattern is that internet users have greater access to help about a variety of things.

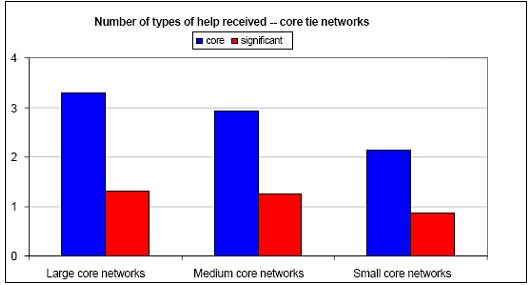

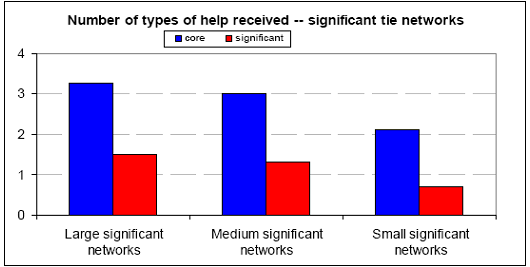

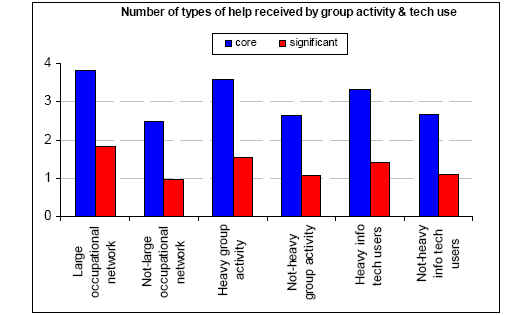

Of course, getting help for various problems is bound to vary by a number of factors, not just internet use. As Figures 10 and 11 show, people with large social networks, those who know people across a wide range of professions, and those who are participants in many community groups have access to the most help.21 People who are fairly heavy users of information and communication technologies are also more likely than average to report high levels of receiving help when they need it.

The definitions for the items in the figures below are as follows:

- The definitions of large, medium, and small networks are the same as those used earlier in the report.22

- Heavy users of communication technologies are defined as those who said they used, within the past month, at least five of the seven technologies we surveyed: cell phone, digital camera, PDA, email, IM, wireless internet, and a cell phone that permits text messaging.

- To measure the scope of occupational acquaintances, respondents were asked if they knew people in the following professions: lawyer, truck driver, sales/marketing manager, pharmacist, janitor/caretaker, engineer, cashier, waiter/waitress, computer programmer, or carpenter. People who know people in 5 or more of the 10 occupations listed are considered to have a large occupational network. The average is 2.7.

- To measure membership in community groups, respondents were asked whether they had been members in the last three years of a: business or professional organization, labor union, sports league (for self or child), religious organization, hobby group, community service group, political group, or other kind of group. Heavy participants in group activity are defined as those who answered “yes” to four on that list (the average is just under two).

Figure 10

Figure 11

The patterns in these charts are not too surprising in some respects. In asking respondents if they turn to their personal networks for help in certain areas, one would expect that large personal networks — either core or significant — are associated with better access to resources that might yield help.

Focusing on the role of core ties, people with a large number of core ties can rely on those people for help, but they tend not to be greatly reliant on their significant ties for help (see Figure 10). Turning to people with large networks of significant ties, they seem to get the best of both worlds — they get about the same amount of help as those rich in core ties, but they are better able to get help from their large pool of significant ties (see Figure 11).

As Figure 12 shows, those who are more heavily involved in community or professional groups, or who know people across a wide range of occupations, are more likely to draw on those networks for help. Relatively heavy users of information technology tend to get more help from their personal networks than those who don’t as much use information technology.

Figure 12

Even though core ties tend to be more frequent sources for help than significant ties, significant ties can be important on the margins. Such weaker ties have their largest payoffs when it comes to changing jobs, finding new places to live, or decisions relating to voting, investments, or buying a computer. For help about medical or health issues (i.e., looking for information about an illness or needing help in caring for someone with a major illness), core ties trump significant ties as sources for help.

The newer technologies — email and cell phone — seem to smooth more paths toward getting help than traditional means.

Earlier in this report, we discussed how people use communication technologies to keep up with people in their social networks, with a focus on how these patterns change as network size grows. As network size grows, people contact a lower share of their social networks for all communication technologies (as well by in-person contact), with the exception of email. For email, the share of a person’s social network contacted on a weekly basis does not decline as network size increases and, as also noted, email does not displace other forms of keeping up with core and significant ties.

The analysis in this section looks at whether there is a relationship between contacting a large share of people’s social networks and getting help — taking into account the different means people use to stay in touch with their core and significant ties.

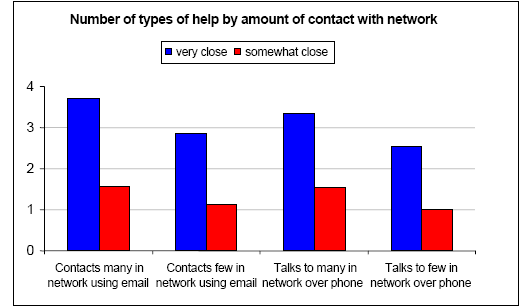

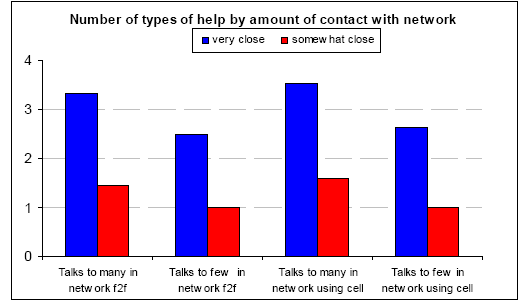

The figures below are built on the question in the Social Ties survey that asked respondents to tell us how many of their core or significant ties they contact at least once a week using a specific tool or means. Below are definitions of those who contact many or relatively few people in their social networks:

- For email, those who contact 8 or more people in their network per week are defined as heavy users of email to keep up with people, while those who contact 2 or fewer by email are defined as light users of email for keeping up with their social networks.

- For cell phone, those who contact 11 or more people per week are heavy contactors, while those who contact 3 or less are light contactors.

- For the landline telephone, those who contact 12 or more people per week are heavy users, while those who contact 3 or less are light contactors.

- For in-person contact, those who contact 18 or more people per week are heavy contactors, while those who contact 7 or less are light contactors.

Heavy users of a particular means of contact are those persons in the upper 33% of the distribution, i.e., they contact the highest share of their networks using a particular tool on a weekly basis. Light contactors are in the lower third of the distribution.

Figure 13

Figure 14

One general pattern is that the newer technologies of email and the cell phone seem to smooth more paths toward getting help than traditional means. Does this mean that email is a better way for getting help via one’s social networks than the phone or an in-person visit? That may be the case because the purpose of using email to contact people in your social network may be to get help — at least to a greater extent than calling someone on the phone to chat or paying them a visit. As the Pew Internet & American Life Project documented in its longitudinal study “Getting Serious Online,” people show a tendency over the course of time to use email for weighty or urgent purposes.23 In other words, face-to-face visits or phone chats may not have getting help as their purpose, while sending an email may be more likely to be intended for that.

It is difficult, then, to conclude that email or cell phones are better resources for maintaining supportive networks. The findings do suggest that email and cell phones are handy tools for keeping in touch with social networks — with the benefit that network members can become aware of problems and offer help and advice when needed.

The internet and other communication technologies often serve as bridges to help.

The internet and other communication technologies often serve as bridges to help. But is there a clear “internet effect” that can be identified in these exchanges in social networks? Perhaps communication technologies are additional channels that open doors to sources of help. Or maybe they let people cultivate and maintain ties with acquaintances that are called upon to provide help or advice at certain times.

It may also be the case that the apparent link may be an artifact of something else. Active internet, IM, or cell phone users are likely to be people with a wide range of acquaintances or who are involved in a lot of group activities. These factors are clearly correlated with greater access to help.

Statistical analyses that disentangle these effects show that technology use independently affects access to help. Regression analysis is the method used to examine whether email or internet had an independent effect on access to help, controlling for other factors such as education, age, familiarity with people in a variety of professions, and network size, which might also have independent effects on access to help.

As it turns out, even though knowing lots of people from different occupations is a very good predictor of access to help, internet use and the use of other communication technologies are, separately and independently, positive predictors of access to help. Specifically, use of the internet alone and email use in the past month are both independently associated with access to help.

People draw on their network capital when they need help. The internet and other communication technologies play an important supporting role in maintaining or cultivating social networks so that they can be called upon when needed.

To look at the internet effect in a different way, the same kind of analysis was done focusing on the communication tools discussed in the previous section, namely the number of core and significant ties contacted by respondents at least weekly. Here the question is whether, when all other factors are held constant, email and cell phone are associated with greater levels of getting help.

The results point to email contact having a positive impact on access to help. An increase in the amount of email contact in their networks has a positive impact on the amount of help people receive — holding other things constant. Of the other types of contact asked about, landline telephone contact also has a positive impact on getting help, while IM and cell phone contact do not have any effect.

The upshot of this analysis is that people draw on their network capital — whether it is people in their social networks, people they know in various professions, or those they meet in the course of more formal professional, hobby, or social groups — to try to address issues that arise in their lives. The internet and other information and communication technologies help in this process.

The internet and email use play a prominent role when compared with other factors. To be sure, knowing more people in a variety of different professions makes the biggest difference for people. Knowing a person in one additional profession has an impact on the amount of types of help a person can get that is about three times as large as being an email or internet user. Still, internet or email use has an impact on the types of available help that is greater than being in a professional or business association, belonging to a religious organization, or participating in a hobby group.24