Introduction

“The qualifications for self-government are not innate,” wrote Thomas Jefferson, “but rather are the result of habit and long-training.”57 Indeed, the development of citizens, key to the perpetuation of a healthy democracy, is a task for every generation.

As noted in the introduction to this report, many see a need to strengthen youth civic outcomes.58 Whether and under what circumstances youth video game play is likely to help or hinder such efforts, however, is not well understood.

Given the ubiquity of video games and their potential impact on the civic lives of teens, this report considers the positive and negative relationships that may exist between game play and civic and political engagement.

Are there connections between games and civic life?

Civic and political engagement in a democratic society include individual and collective efforts to identify and address issues of public concern. These actions range from individual volunteerism, to organizational involvement, to electoral participation.59

Currently, little is known about the influence of video games on youth civic engagement. There have not yet been many studies that examine, for example, whether civic development is supported by such civic gaming experiences as creating a virtual nation, working with others cooperatively, expanding one’s social network online, and helping less experienced players play games. The relationships between similar civic activities in other domains and civic outcomes, however, have been studied.

Civic education researchers have conducted longitudinal and quasi-experimental studies that examine the relationship between both school-based civic learning opportunities and social contexts, on the one hand, and young people’s civic and political engagement, on the other. In that research, the opportunities and contexts found to be effective include: learning about how governmental, political, and legal systems work; learning about social issues; volunteering to help others; participating in simulations of civic and political activities; and participating in extracurricular activities where young people can practice productive group norms and expand social networks.

When these experiences are provided to young people in school and in after-school settings, particularly to adolescents who are at a critical age for the development of civic identity, studies have found increases in their commitment to civic and political participation.60 The widespread popularity of video games among teens raises the question of whether video games can provide similar opportunities for civic and political engagement with the same results.

This report defines “civic gaming experiences” as experiences young people have while gaming that are similar to offline experiences in classrooms and schools that research has found promote civic and political engagement in young people.

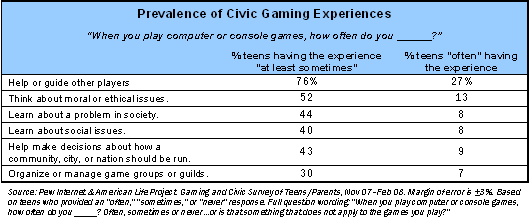

The civic gaming experiences that we measured include:

- Helping or guiding other players.

- Playing games where one learns about a problem in society.

- Playing games that explore a social issue the player cares about.

- Playing a game where the player has to think about moral or ethical issues.

- Playing a game where the player helps make decisions about how a community, city or nation should be run.

- Organizing game groups or guilds.

The Gaming and Civics Survey measures the quantity, civic characteristics, and social context of gaming, while also measuring the civic and political commitments and activities of teens. It is the first large-scale study with a nationally representative sample that measures how frequently youth have civic gaming experiences, the social contexts of gaming, and the relationship between the civic content and social context of game play and varied civic outcomes on the other.

Some civic gaming experiences are more common than others.

Between 30% and 76% of teens have these civic gaming experiences “at all.” Relatively few teens reported often having a specific civic gaming experience “often.”

Teens have varying levels of civic gaming experiences.

Individuals also report differing amounts of civic gaming experiences. Teens who have the least civic gaming experiences (those in the bottom 25% of the distribution of civic gaming experiences) report sometimes helping or guiding other players, but are unlikely to report having any other civic gaming experiences. Teens who have average civic gaming experiences (those in the middle 50% of the distribution of civic gaming experiences) typically have had several civic gaming experiences at least sometimes, with a small number of civic gaming experiences occurring often. Teens who have the most civic gaming experiences (those in the top 25% of the distribution of civic gaming experiences) typically have had all the civic gaming experiences at least sometimes, as well as some civic gaming experiences often.

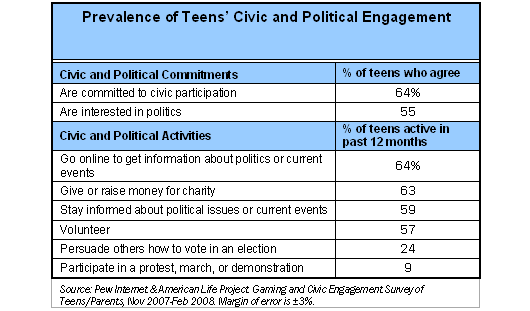

Roughly 60% of teens are interested in politics, charitable work, and express a sense of commitment to civic participation.

On the whole, teens are likely to report getting information about politics, raising money for charity, and expressing a sense of responsibility for and commitment to future civic participation, with (64%) of teens reporting these outcomes. More than half of all teens volunteer, stay informed about political issues, and are interested in politics. Teens are far less likely to report trying to persuade someone how to vote in an election (24%) or taking part in a protest march or demonstration (9%).

The quantity of game play is not strongly related (positively or negatively) to most indicators of teens’ interest and engagement in civic and political activity.

Analyses compared the civic and political attitudes and behavior of teens who play games every day or more, those who play games one to five times per week, and teens who play games less than once a week. For all eight indicators of civic and political engagement, there were no significant differences between teens who play games every day and teens who play less than once a week (after controlling for demographics and parents’ civic engagement). For six of the eight indicators, there were no significant differences between teens who play games one to five times a week and teens who play less than once a week. The exception was that 11% of teens who play games one to five times a week have protested in the last 12 months, compared with 5% of teens who play less than once a week, and 57% of teens who play games one to five times a week say they are interested in politics, compared with 49% of teens who play less than once a week (see Table 1 in Appendix 2 for details).

Within the group of teens who play games every day, time spent gaming varied from 15 minutes to several hours each day. The relationship between the number of hours teens played games the previous day and civic outcomes was statistically significant for two of the eight outcomes asked about. Teens who spend more hours playing games are slightly less likely to volunteer or to express a commitment to civic participation than those who play for fewer hours (see Table 2 in Appendix 2 for details).

The characteristics of game play are strongly related to teens’ interest and engagement in civic and political activity.

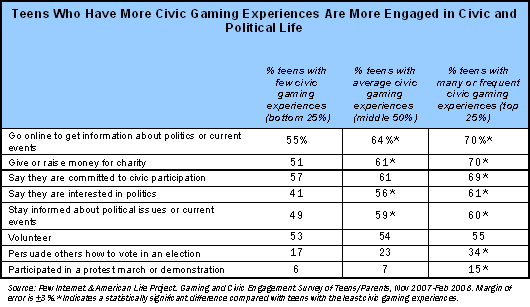

Teens who have civic gaming experiences report much higher levels of civic and political engagement than teens who have not had these kinds of experiences (see Table 3 in Appendix 2 for details). These differences were statistically significant for all eight of the civic outcomes considered.

Among teens who had the most civic gaming experiences—those in the top 25% of our sample who had many of the experiences at least “sometimes” and several experiences frequently:61

- 70% go online to get information about politics or current events, compared with 55% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 70% have raised money for charity in the past 12 months, compared with 51% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 69% are committed to civic participation, compared with 57% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 61% are interested in politics, compared with 41% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 60% stay informed about current events, compared with 49% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 34% have tried to persuade others to vote a particular way in an election, compared with 17% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 15% have participated in a protest, march, or demonstration, compared to 6% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

Among teens who reported having average amounts of civic gaming experiences—that is, those in the middle 50% of our sample who had several civic gaming experiences “sometimes” or a small number “frequently”:

- 64% go online to get information about politics or current events, compared with 55% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 61% have raised money for charity in the past 12 months, compared with 51% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 59% stay informed about political issues or current events, compared with 49% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

- 56% are interested in politics, compared with 41% of those who have the least civic gaming experiences.

Playing games with others in person is related to civic and political outcomes, but playing with others online is not.

Teens who play games socially are more likely to be civically and politically engaged than teens who play games primarily alone. However, this is only true when games are played with others in the same room. Teens who play games with others online are no different in their civic and political engagement than teens who play games alone (see Table 4 in Appendix 2 for details).

Among teens who play games with others in the room:

- 65% go online to get information about politics, compared to 60% of those who do not.

- 64% have raised money for charity, compared to 55% of those who do not.

- 64% are committed to civic participation, compared to 59% of those who do not.

- 26% have tried to persuade others how to vote in an election, compared to 19% of those who do not.

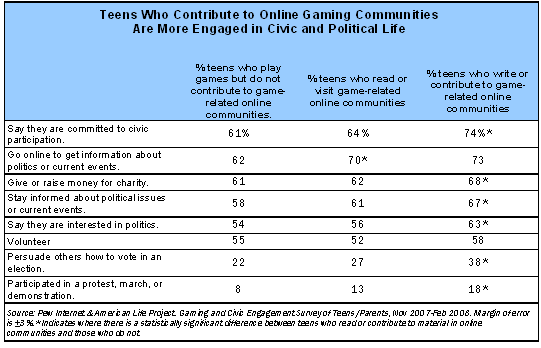

Youth who take part in social interaction related to the game, such as commenting on websites or contributing to discussion boards, are more engaged civically and politically. Youth who play games where they are part of guilds are not more civically engaged than youth who play games alone.

In order to determine whether the lack of relationship between civic outcomes and playing with others online was due to the depth of interactions that occur online, different kinds of online gaming relationships were considered. Playing with others online can be a fairly weak form of social interaction where players do not interact directly and only play for a short time, or it can include longer and more sustained networks where players join a guild and/or play games in an ongoing, interactive fashion. New media scholars suggest that the more intensive socializing one sees in guilds offers many benefits of offline civic spaces62 that less-intensive online play does not. To shed light on this issue, we compared those who participate in guilds and those who only play alone.

There was no difference between the two groups’ level of civic and political engagement. Among teens who read or visit websites, reviews, or discussion boards related to games they play, 70% go online to get information about politics or current events, compared with 60% of teens who play games but do not do this (see Table 5 in Appendix 2 for details).

Among teens who write or contribute to game-related websites:

- 74% are committed to civic participation, compared with 61% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

- 68% have raised money for charity, compared with 61% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

- 67% stay informed about current events, compared with 58% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

- 63% are interested in politics, compared with 54% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

- 38% have tried to persuade others how to vote in an election, compared with 22% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

- 18% have protested in the last 12 months, compared with 8% of those who play games but do not contribute to online gaming communities.

Civic gaming opportunities appear to be more equitably distributed than high school civic learning opportunities.

The fact that civic gaming experiences are strongly related to many civic and political outcomes raised the question of how equitably they were distributed. Previous research has found that the high school civic learning opportunities that promote civic and political commitments and capacities tend to be unequally distributed with higher-income, higher-achieving, and white students experiencing many more opportunities than their counterparts.63

This, however, was not the case for civic gaming opportunities. Only gender is related to whether teens have access to these opportunities. Overall, 81% of boys reported having average or frequent civic gaming experiences, compared to 71% of girls. Income, race, and age were all unrelated to the amount of civic gaming experiences reported by respondents (see Table 6 in Appendix 2 for details).