Overview

Cast a glance at any coffee shop, train station, or airport boarding gate, and it is easy to see that mobile access to the internet is taking root in our society. Open laptops or furrowed brows staring at palm-sized screens are evidence of how routinely information is exchanged on wireless networks. But the incidence of such activity is only one dimension of this phenomenon. Not everyone has the wherewithal to engage with “always present” connectivity and, while some may love it, others may only dip their toes in the wireless water and not go deeper. Until now, it has not been clear how mobile access interacts with traditional wireline online behavior. Does availability of mobile access crowd out desktop access? Does it draw some users further into digital lifestyles?

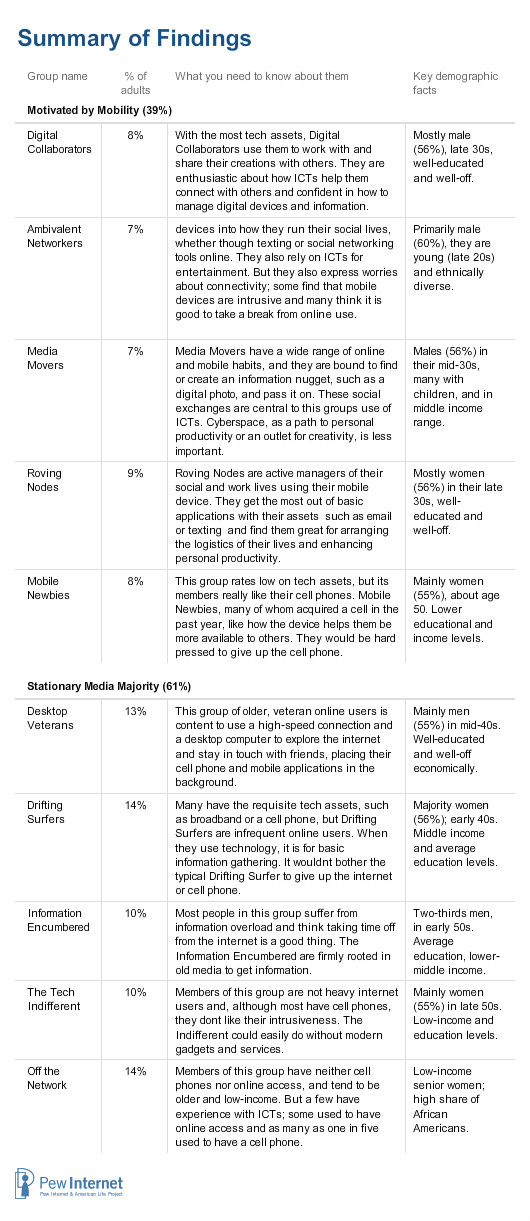

The role of mobile internet access in evolving digital lifestyles is the cornerstone of the second typology of information and communication technology (ICT) users developed by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project.1 The typology places ICT users into 10 groups and, notwithstanding variation across the groups, the groups fit into two baskets, with the groups’ collective judgments on mobility being the pivot point.

- Motivated by Mobility: Five groups in this typology – making up 39% of the adult population – have seen the frequency of their online use grow as their reliance on mobile devices has increased. For these groups, growth in frequency of online use is linked not only to increasing broadband adoption, but to positive and improving attitudes about how mobile access makes them more available to others. Across the groups, a lot of variation exists regarding what these changes mean to users. Some find this extra connectivity a platform for self expression. Others are not entirely positive about ICTs’ impacts on their lives.

- Stationary media will do: The remaining 61% of the adult population does not feel the pull of mobility – or anything else – drawing them further into the digital world. Across the five groups that make up this part of the population, several have a lot of technology at hand and have seen their tech assets grow in recent years. Yet ICTs remain on the periphery in their lives, suggesting that some adult Americans reach a plateau in their technology use. Some groups are content with this distant relationship to technology. For others, even a little modern gadgetry is too much.

For 39% of the adult population, mobile and wireline access tools have a symbiotic relationship. Mobile users typically have ready access to high-speed connections at home, which likely pushes them toward deeper home high-speed use; the digital content found on the mobile device may prompt more activity on their broadband-enabled big screen at home. At the same time, the desktop internet experience migrates to “on the go” as the handheld becomes a complementary access point to connect with people and digital content wherever a wireless network reaches.

The five groups reliant on stationary media tools show no growth (or declines) in the frequency of online use even though more of them have broadband access. They show low levels of use of mobile applications and decidedly tepid attitudes about ICTs. In other words, 61% of the adult population have a settled disposition toward ICTs and – whether they experience information overload, difficulties in getting gadgets to function, or frustration when the cell phone rings – are not rapidly becoming more active users of ICTs.

Although the groups in the two baskets share common patterns with respect to mobile ICT uses, each group has a distinct disposition toward ICTs. Some are contentedly and deeply engaged with ICTs, others mainly use traditional applications on the wireline internet to carry out tasks, while some keep modern gadgetry and services at arm’s length.

As in the Project’s first typology, this year’s typology revolves around people’s relationships to ICTs in three areas:

- Assets (the gadgets and services they have);

- Actions (what they do with what they have); and,

- Attitudes (what they think about how ICTs fit into their lives).

The second typology is based on a December 2007 survey of 3,553 American adults. The typology has a longitudinal element to the analysis, as it uses a callback survey of 1,499 respondents from our 2006 typology that has been integrated into the 2,054 newly-interviewed respondents in December 2007. Although the current typology, through the callback element, builds on the 2006 typology, the user groups we identify in this typology differ from the ones developed from the 2006 survey. That is, while some groups in this typology may bear some resemblance to ones from the 2006 typology, the 2007 groups do not map backwards to 2006 groups or represent how any 2006 group has evolved in the 20 months between surveys.2 The longitudinal data does, however, come into play in tracking people’s attitudes toward their ICTs over time.

The following table summarizes how the groups use ICTs and group members’ attitudes about them, and the Summary continues with more detailed sketches of the groups and a discussion of the report’s implications.

Digital Collaborators: 8% of adults use information gadgets to collaborate with others and share their creativity with the world.

For many Digital Collaborators, digital information is input into a creative process that often involves others and whose output they share with the world using the web. Members of this group can almost always get access to the internet, whether that is with an “always on” broadband connection or with an “always present” mobile device. With such robust connectivity, Digital Collaborators share their thoughts or creative content with others. Using blogs and other content-creation applications, they collaborate with others online to express themselves creatively. For Digital Collaborators, the internet can be a camp, a lab, or a theater group – places to gather with others to develop something new.

This pattern of active and continuous information exchange puts ICTs at the center of how Digital Collaborators learn, work, socialize, and have fun. Most play games on electronic devices, with half playing games on the internet. At least occasionally, most of them watch TV on a device other than a traditional television set. And one-quarter have avatars that let them participate in virtual worlds. The typical Digital Collaborator is in his late 30s and has had years of online experience to hone his skills to get the most out of ICTs.

Ambivalent Networkers: 7% of adults heavily use mobile devices to connect with others and entertain themselves, but they don’t always like it when the cell phone rings.

Digital information flows through handheld devices and social networking sites for Ambivalent Networkers as they have seamlessly integrated these cutting-edge resources into how they connect with others. With a handheld device at the ready, Ambivalent Networkers stay in touch with their family and friends and gather intelligence about what is going on in the world. They are the most frequent cell phone texters of any group. While some message content might be about current affairs, a portion is undoubtedly about culture, as Ambivalent Networkers will watch videos or listen to music using online access tools, mobile or otherwise.

While they welcome the connections to people and knowledge that easy access opens, Ambivalent Networkers don’t always like a knock on their door. Like Digital Collaborators, frequent information exchange is a key part of Ambivalent Networkers’ profiles. Unlike Digital Collaborators, they sometimes struggle with traffic volume. They are less likely than average to enjoy the extra availability enabled by mobile devices and less certain than Digital Collaborators about whether ICTs offer them more control over their lives. Most Ambivalent Networkers say they think it is a good idea to take a break from using the internet. Nonetheless, they are confident in their ability to manage gadgets and would be hard pressed to do without mobile access.

Media Movers: 7% of adults use online access to seek out information nuggets, and these nuggets make their way through these users’ social networks via desktop and mobile access.

Media Movers create and manage a steady stream of information throughput using a range of devices. The typical Media Mover, a mid-30s male, may have a knapsack full of devices such as a video or digital camera ready at an instant to record something and, before long, send it along to a friend or post it online. Such social uses for ICTs draw most of the attention of Media Movers; for them ICTs aren’t principally about improving personal productivity or doing their jobs.

The cell phone might be the hook that draws this group closer to digital tools and activities. Although Media Movers are less active mobile users than the previous two groups, they are far happier about the cell phone’s presence in their lives than Ambivalent Networkers. Media Movers are more likely than average to use their cell phone for functions such as texting, taking pictures, or playing games. Media Movers’ attachment to their cell phone has deepened over time, whereas similar such attitudes about the internet have not changed.

Roving Nodes: 9% of adults use their mobile devices to connect with others and share information with them.

Picture a Roving Node as a woman in her late 30s who is rarely without her smart phone, often using it to chat, but also checking email or fielding a text message. When she gets home or back to the office, she is frequently online, keeping up with email or surfing the net to get news or shop. This group is highly dependent on ICTs, and this dependence comes about from using ICTs to manage busy lives and stay in touch with others. Unlike the groups above, Roving Nodes are more hubs of information flows than sources of digital content. They are heavily reliant on all their ICTs for communicating and gathering information, but Roving Nodes are much less likely than preceding groups to blog or manage their own web pages.

Roving Nodes are happy when the cell phone rings, which sets them apart from Ambivalent Networkers. Although they like how gadgets help them share their ideas with others, it is not likely that a blog or an update to their webpage will be the means to do this. Give Roving Nodes email access, a browser, and a cell phone, and they are off connecting to others and passing information along the network.

Mobile Newbies: 8% of adults lack robust access to the internet, but they like their cell phones.

A typical Mobile Newbie, who is about 50 years old, is a novice with modern ICTs, but is wading into the waters thanks to a new cell phone. The Mobile Newbie might have gotten the phone because she thought it would be a handy tool for staying in touch with others or perhaps even for safety reasons. The cell phone is the device that is generally a Mobile Newbie’s introduction to modern ICTs; nearly all have one and many got it in the past year. Just four in ten use the internet. When the cell phone buzzes, they are pleased to answer. Mobile Newbies will also occasionally send a text message or snap a picture with their handheld device. Over time, they have found the cell phone more to their liking, while the internet remains an infrequent part of their daily rhythms.

This group is collectively new to the internet, having only gotten access about two years ago. Usability of information technology may be an issue here. Most in this group say they need help setting up new devices and services. But they seem nonetheless attached to their cell phone, as most would find it hard to give up – a sentiment that has grown over time.

These five groups make up the 39% of American adults who make up the basket of groups we call “Motivated by Mobility.” The profiles of the other 61%, the “Stationary Media Majority,” start here.

Desktop Veterans: 13% of adults are dedicated to wireline access to digital information, and like how it opens up the pipeline to information for them.

This group consists mostly of veteran online users (mostly men) who enjoy going online to check email and get news. Desktop Veterans are enthusiastic about how this lets them stay in touch with others and learn new things. They even share some of what they find online through blogs (either their own or a group blog) and by posting comments online.

However, they have yet to venture into the world of mobile access on a handheld, at least to any great extent. Desktop Veterans are average in terms of cell phone adoption, but well below average in their use of non-voice data applications such as text messaging or wirelessly browsing the internet. They use the cell to make phone calls, but even then the cell phone takes a backseat to their reliance on the landline for calls. Collectively, Desktop Veterans have the feel of a very tech-oriented group – from 2004. They have high rates of broadband adoption and participate in the online commons, but they treat the cell phone as if it were equipped only with voice capability – like most cell phones circa 2004.

Drifting Surfers: 14% of adults are light users – despite having a lot of ICTs – and say they could do without modern gadgets and services.

This group of adults has a fair amount of online experience (8 years) but, in spite of high home broadband adoption, they are infrequent users of the internet. Digital information is not at the center of how they get information, keep in touch with people, or do their jobs.

Although they rely about equally on their landline and cell for phone calls, they don’t find the extra availability afforded by cell phones very alluring. Like Desktop Veterans, they haven’t bothered to exploit other uses of cell phone, save to swap an occasional text message. Unlike Desktop Veterans, Drifting Surfers do not have strong attachments to the internet. Drifting Surfers are much less likely than Desktop Veterans to say ICTs help them learn new things, do their jobs, or keep in touch with others. They would not find it hard to give up their cell phone, and the typical Drifting Surfer found it easier to give up the cell phone in 2007 than 2006.

Information Encumbered: 10% of adults feel overwhelmed by information and inadequate to troubleshoot modern ICTs.

For the Information Encumbered, the pipeline of digital information is increasingly a burden. This group of (mainly) men in their mid-50s has the means and experience to engage with the information superhighway. Three-quarters have a cell phone and half have high-speed at home, and the typical member of this group has been online since about 2000. But half feel the weight of information overload, which is the highest of any group in the typology and an increase since 2006. Nearly two-thirds need help in getting their technology to work.

Beyond a sense that modern ICTs are worthwhile ways to keep in touch with others, the Information Encumbered do not credit the internet or cell phone with any improvement in their personal productivity or how they do their jobs. Some of their attitudes toward ICTs – such as worries about information overload – have worsened over time. Whereas Drifting Surfers and Desktop Veterans either like or tolerate gadgets and the modern flow of information, this is not the case for the Information Encumbered.

The Tech Indifferent: 10% of adults are unenthusiastic about the internet and cell phone.

For the Tech Indifferent, modern gadgets and services are too much trouble with too little payoff. This group is twice as likely to have a cell phone as online access, but they use neither service very often. The Tech Indifferent are, as a group, older than the others and seem to have established patterns of getting information or staying in touch with family and friends that do not rely on modern Tech.

The Tech Indifferent don’t see modern gadgetry as a tool for having more control over their lives, and, when they adopt a new device or service, they generally need help getting it to work. With many in this group saying they feel information overload and fewer saying they like how ICTs make them more available to others, there is little reason to think that many in this group will ever embrace modern ICTs.

Off the Network: 14% of adults are neither cell phone users nor internet users.

Although members of this group currently lack online access and a cell phone, some have had past experience with these technologies. Perhaps the computer stopped working and they were uncertain why or how to go about fixing it. Maybe the cell phone plan became too expensive or an “Off the Network” group member used it so little she decided to cancel service. They are the oldest and least affluent group in the typology.

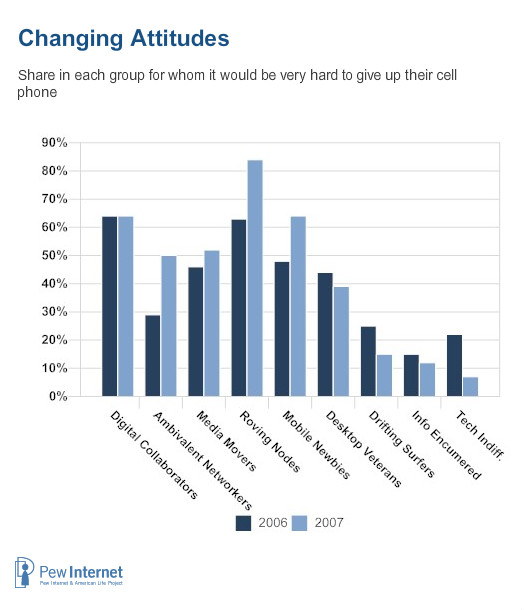

Most “motivated by mobility” groups have positive and improving attitudes about cell phones, while remaining groups have tepid and deteriorating attitudes about them.

A key factor in sorting the 10 groups into two baskets is how they feel about cell phones. Those groups in the “motivated by mobility” basket have positive and improving attitudes about cell phones, as measured by the share of cell users in each group who say it would be “very hard” to do without cell phones. All of the “motivated by mobility” groups share two characteristics:

- They have a majority of cell users who say they would find it very hard to give up their mobile device.

- The share in each group saying it would be very hard to give up their mobile device has grown in the 2006 to 2007 timeframe.

In the “stationary media majority” groups, none has a majority of cell users saying it would be very hard to give up their cell, and all have seen a decline in the twenty months between our tech-user surveys in the share of people saying they would find it very hard to give up the cell phone. The table below summarizes these points.

Overall:

- 66% of those in the “motivated by mobility” groups report that it would be very hard to do without their cell phones.

- This contrasts sharply with the 21% figure for the “stationary media majority” groups.

- “Motivated by mobility” groups collectively showed an improvement in cell phone attitudes by 20% from 2006 to 2007.

- Again, in stark contrast, the “stationary media majority” groups collectively saw a 64% decrease in attitudes about cell phones from 2006 to 2007.

Deepening attachment to digital resources – wired and wireless – means connectivity is for many users now about continual information exchange.

For many in the “motivated by mobility” groups, a multiple platform world creates a virtuous cycle with respect to digital resources: “Always on” broadband draws them down a path of digital engagement that “always connected” mobile access deepens and accelerates.

Some 31% of adults say that very frequent information exchanges over high-speed wires and mobile devices are cornerstones of their digital profiles. These are the adults in the following groups: Digital Collaborators, Ambivalent Networkers, Media Movers, and Roving Nodes.

The bar for what qualifies as high-tech among users has risen.

In the Pew Internet Project’s first typology, tech-oriented users were generally those who had broadband at home. This typology largely abandons that dichotomy with its focus on people’s attitudes and use of mobile devices and applications. In the past, having tech gear such as broadband at home generally placed people on the cutting edge; that is no longer the case in this edition of the typology. Our new study shows that mobile connectivity is the new centerpiece of high-tech life.

That means that two groups who used to seem high tech seem less so nowadays. They are the Desktop Veterans and the Drifting Surfers. They make up 26% of the adult population, and they have broadband adoption rates of about 80%. But their occasional use of mobile applications and decidedly lukewarm attitudes toward them leave them off the cutting edge.

The “penalty” for having little or no access rises in a multi-platform world.

As a large portion of the online population gravitates to wireless and mobile access to supplement their home high-speed wired connections, the supply of and demand for online content increases. Institutions – whether governments or news organizations – have greater incentives to optimize their services to be consumed online. More people have greater opportunity to share their advice, creativity, and observations online.

Recent research argues that exclusion from (or low levels of engagement with) the network of people and information found online is more costly than in the past.3 In this typology, four groups making up 42% of the population have both below average levels of broadband and uses of mobile and online resources. Those groups are Drifting Surfers, Information Encumbered, Mobile Newbies, and Off the Net.