The internet provides access not only to information, but also to each other.

The Pew Internet Project and California HealthCare Foundation have long been interested in the impact of the internet on health and health care, measuring how many people have access to technology, how they use it to gather information, and what topics are of greatest interest.1 A primary finding of our research is that health professionals continue to play a central role in most people’s lives when it comes to being sick, getting well, and maintaining good health, no matter the level of internet access someone may have.2

However, the internet has not only facilitated increased patients’ access to information, but it has also enabled new pathways for patients to find and help each other. Social network sites, blogs, online communities, email groups and listservs, and other tools allow people to express themselves in ways that respond immediately to people. But those messages also persist – and are often searchable and can help patients in the future. People use the internet to find others who share the same interests, whether in politics, hobbies, music, health, or any other topic, no matter where they may live. Social tools also deepen people’s connections to groups they join offline and draw them to join new groups formed online. Indeed, 46% of internet users who are active in groups say the internet has helped them to be active in more groups than would otherwise be the case.3

Over the last few years, the popular imagination has been captured by the possibility that people can use digital tools to reorganize segments of society.4 A revolution in health care is running along a parallel track, mixing people’s instincts to share knowledge with the social media that make it easy, creating what might be called “peer-to-peer healthcare.”

Taking the social life of health information to the next level.

This report is based in part on a national telephone survey of 3,001 adults which captures an estimate of how widespread this activity is in the U.S. All numerical data included in the report is based on the telephone survey. The other part of the analysis is based on an online survey of 2,156 members of the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) who wrote short essays about their use of the internet in caring for themselves or for their loved ones.

NORD represents the approximately 25 million Americans living with a rare disease, which is defined as affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. The people who participated in the online survey reported a wide array of conditions, such as Marfan’s Syndrome, congenital hyperinsulinism, and aplastic anemia, to name just a few. In reading those essays, it becomes clear that the people who responded to the survey have taken the social life of health information to the next level. Many of them forged a long path toward a diagnosis (if they even have one) only to find out that this was simply the start of another journey.

People living with rare disease, their own or a loved one’s, have honed their searching, learning, and sharing skills to a fine point. They endlessly scan resources for clues to try to cope with and mitigate the inevitable complications and setbacks that come from rare diseases. What was once a solitary expedition for one person or one family, however, has become a collective pursuit taken on by bands of brothers- and sisters-in-arms who may never meet up in person.

Many Americans turn to friends and family for support and advice when they have a health problem. This report shows how people’s networks are expanding to include online peers, particularly in the crucible of rare disease.

“We can say things to each other we can’t say to others.”

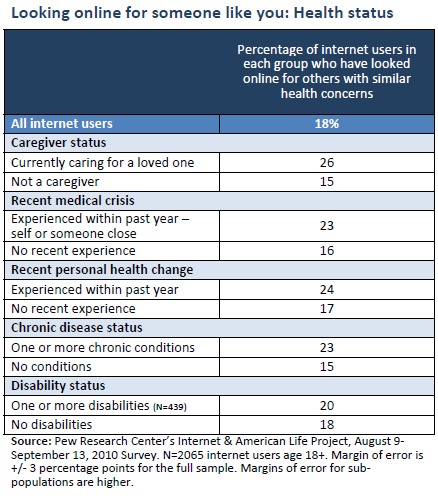

One in five internet users (18%) have gone online to find others who might have health concerns similar to theirs.

Internet users ages 65 and older are less likely than younger internet users to have done this (10%, compared with 18% of those ages 50-64, for example). Spanish-dominant internet users are also significantly less likely than English-dominant internet users to have looked online for someone with similar health concerns (6%, compared with 19%).

Twenty-three percent of internet users living with chronic conditions have looked online for someone with similar health concerns, compared with 15% of those who report no conditions. In the survey, we asked about chronic conditions in two ways: First, we asked people if they had one of five conditions: high blood pressure, diabetes, lung conditions, heart conditions, or cancer. All of the internet users who had at least one of those conditions are equally likely to have looked online for someone with similar health concerns.

Our second strategy in looking at chronic disease was to ask people if they had any other condition besides the one we mentioned. Some 17% of respondents say they do. It is intriguing that a greater proportion of these internet users living with less common, chronic health problems have gone online to find others with similar health concerns. Thirty-two percent of internet users in that group say they have done so, compared with 15% of internet users who have no chronic conditions.

Internet users who have experienced a recent medical emergency, their own or someone else’s, are also more likely than other internet users to go online to try to find someone who shares their situation: 23%, compared with 16%. This fits the pattern observed in other research that people going through a medical crisis are voracious information consumers: 85% say they look online for health information, compared with 77% of internet users who have not had that experience in the past year.5

Internet users who have experienced a significant change in their physical health, such as weight loss or gain, pregnancy, or quitting smoking are also more likely than other internet users to have looked online for someone like them. This is not new behavior, of course, as any member of Weight Watchers or a new mothers’ playgroup can attest. However, the internet widens the network available to people and allows behavior change to spread in new ways. Ex-smokers can support each other through nicotine cravings at any time of the day or night, for example, and studies have shown that the more help someone receives, the more likely they will help someone else.6

Rare disease seems to amplify this need to spread one’s network far and wide. And this more extended network sometimes can bring special benefits. Patients say they will confide to others in these extended networks in ways that are sometimes hard to confide to their closest family members and friends. A woman living with a blood disorder wrote in the online survey about her support group: “We can say things to each other we can’t say to others. We joke about doctors and death. We cry when we need to. Together we are better informed. The support is powerful and empowering.”

In a book about rare-disease caregivers, Uncommon Challenges; Shared Journeys, one mother wrote, “Before the internet, we were alone. In 1996, when Jacob was born, there was no search engine to offer me any information. Today, because of social media, we are connected with many people who are fighting the same fight as we are. The internet has made our small disease larger and we are able to educate many more people now.”7

[his condition]

The internet can enable connections across distances and among people who may never have met in person. These encounters can have deep and lasting impact on people’s health and well-being, particularly among those who thought they would never find someone who shared their particular situation. For example, an adult living with a rare condition wrote, “The first time I met another patient, face to face, I sobbed. I was overjoyed and began to communicate with them on a regular basis and my network grew.”