Summary of Findings

Privacy evokes a constellation of concepts for Americans—some of them tied to traditional notions of civil liberties and some of them driven by concerns about the surveillance of digital communications and the coming era of “big data.” While Americans’ associations with the topic of privacy are varied, the majority of adults in a new survey by the Pew Research Center feel that their privacy is being challenged along such core dimensions as the security of their personal information and their ability to retain confidentiality.

When Americans are asked what comes to mind when they hear the word “privacy,” there are patterns to their answers. As the above word cloud illustrates, they give important weight to the idea that privacy applies to personal material—their space, their “stuff,” their solitude, and, importantly, their “rights.” Beyond the frequency of individual words, when responses are grouped into themes, the largest block of answers ties to concepts of security, safety, and protection. For many others, notions of secrecy and keeping things “hidden” are top of mind when thinking about privacy.

Most are aware of government efforts to monitor communications

More than a year after contractor Edward Snowden leaked documents about widespread government surveillance by the NSA, the cascade of news stories about the revelations continue to register widely among the public. Some 43% of adults have heard “a lot” about “the government collecting information about telephone calls, emails, and other online communications as part of efforts to monitor terrorist activity,” and another 44% have heard “a little.” Just 5% of adults in our panel said they have heard “nothing at all” about these programs.

Widespread concern about surveillance by government and businesses

Perhaps most striking is Americans’ lack of confidence that they have control over their personal information. That pervasive concern applies to everyday communications channels and to the collectors of their information—both in the government and in corporations. For example:

- 91% of adults in the survey “agree” or “strongly agree” that consumers have lost control over how personal information is collected and used by companies.

- 88% of adults “agree” or “strongly agree” that it would be very difficult to remove inaccurate information about them online.

- 80% of those who use social networking sites say they are concerned about third parties like advertisers or businesses accessing the data they share on these sites.

- 70% of social networking site users say that they are at least somewhat concerned about the government accessing some of the information they share on social networking sites without their knowledge.

Yet, even as Americans express concern about government access to their data, they feel as though government could do more to regulate what advertisers do with their personal information:

- 80% of adults “agree” or “strongly agree” that Americans should be concerned about the government’s monitoring of phone calls and internet communications. Just 18% “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with that notion.

- 64% believe the government should do more to regulate advertisers, compared with 34% who think the government should not get more involved.

- Only 36% “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement: “It is a good thing for society if people believe that someone is keeping an eye on the things that they do online.”

In the commercial context, consumers are skeptical about some of the benefits of personal data sharing, but are willing to make tradeoffs in certain circumstances when their sharing of information provides access to free services.

- 61% of adults “disagree” or “strongly disagree” with the statement: “I appreciate that online services are more efficient because of the increased access they have to my personal data.”

- At the same time, 55% “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement: “I am willing to share some information about myself with companies in order to use online services for free.”

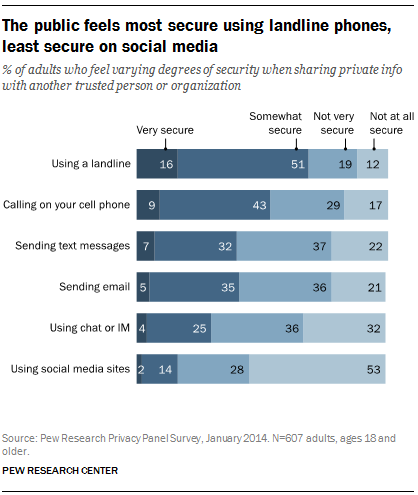

There is little confidence in the security of common communications channels, and those who have heard about government surveillance programs are the least confident

Across the board, there is a universal lack of confidence among adults in the security of everyday communications channels—particularly when it comes to the use of online tools. Across six different methods of mediated communication, there is not one mode through which a majority of the American public feels “very secure” when sharing private information with another trusted person or organization:

- 81% feel “not very” or “not at all secure” using social media sites when they want to share private information with another trusted person or organization.

- 68% feel insecure using chat or instant messages to share private information.

- 58% feel insecure sending private info via text messages.

- 57% feel insecure sending private information via email.

- 46% feel “not very” or “not at all secure” calling on their cell phone when they want to share private information.

- 31% feel “not very” or “not at all secure” using a landline phone when they want to share private information.

Americans’ lack of confidence in core communications channels tracks closely with how much they have heard about government surveillance programs. For five out of the six communications channels we asked about, those who have heard “a lot” about government surveillance are significantly more likely than those who have heard just “a little” or “nothing at all” to consider the method to be “not at all secure” for sharing private information with another trusted person or organization.

Most say they want to do more to protect their privacy, but many believe it is not possible to be anonymous online

When it comes to their own role in managing the personal information they feel is sensitive, most adults express a desire to take additional steps to protect their data online: When asked if they feel as though their own efforts to protect the privacy of their personal information online are sufficient, 61% say they feel they “would like to do more,” while 37% say they “already do enough.”

Just 24% of adults “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement: “It is easy for me to be anonymous when I am online.”

When they want to have anonymity online, few feel that is easy to achieve. Just 24% of adults “agree” or “strongly agree” with the statement: “It is easy for me to be anonymous when I am online.”

Not everyone monitors their online reputation very vigilantly, even though many assume others will check up on their digital footprints

Some people are more anxious than others to keep track of their online reputation. Adults under the age of 50 are far more likely to be “self-searchers” than those ages 50 and older, and adults with higher levels of household income and education stand out as especially likely to check up on their own digital footprints.

- 62% of adults have ever used a search engine to look up their own name or see what information about them is on the internet.

- 47% say they generally assume that people they meet will search for information about them on the internet, while 50% do not.

- However, just 6% of adults have set up some sort of automatic alert to notify them when their name is mentioned in a news story, blog, or elsewhere online.

Context matters as people decide whether to disclose information or not

One of the ways that people cope with the challenges to their privacy online is to employ multiple strategies for managing identity and reputation across different networks and transactions. As previous findings from the Pew Research Center have suggested, users bounce back and forth between different levels of disclosure depending on the context. This survey also finds that when people post comments, questions or other information, they do so using a range of identifiers—using a screen name, their actual name, or posting anonymously.

Among all adults:

- 59% have posted comments, questions or other information online using a user name or screen name that people associate with them.

- 55% have done so using their real name.

- 42% have done so anonymously.

In some cases, the choices people make about disclosure may be tied to work-related policies. Among employed adults:

- 24% of employed adults say that their employer has rules or guidelines about how they are allowed to present themselves online.

- 11% say that their job requires them to promote themselves through social media or other online tools.

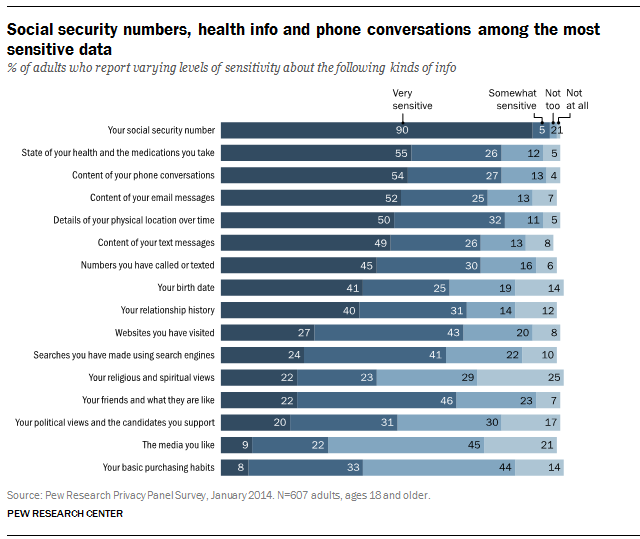

Different types of information elicit different levels of sensitivity among Americans

Social security numbers are universally considered to be the most sensitive piece of personal information, while media tastes and purchasing habits are among the least sensitive categories of data.

At the same time that Americans express these broad sensitivities toward various kinds of information, they are actively engaged in negotiating the benefits and risks of sharing this data in their daily interactions with friends, family, co-workers, businesses and government. And even as they feel concerned about the possibility of misinformation circulating online, relatively few report negative experiences tied to their digital footprints.

- 11% of adults say they have had any bad experiences because embarrassing or inaccurate information was posted about them online.

- 16% say they have asked someone to remove or correct information about them that was posted online.

About this Report

This report is the first in a series of studies that examines Americans’ privacy perceptions and behaviors following the revelations about U.S. government surveillance programs by government contractor Edward Snowden that began in June of 2013. To examine this topic in depth and over an extended period of time, the Pew Research Center’s Internet Project commissioned a representative online panel of 607 adults who are members of the GfK Knowledge Panel. These panelists have agreed to respond to four surveys over the course of one year. The findings in this report are based on the first survey, which was conducted in English and fielded online January 11-28, 2014. In addition, a total of 26 panelists also participated in one of three online focus groups as part of this study during August 2013 and March 2014.

This report is a collaborative effort based on the input and analysis of the following individuals:

Mary Madden, Senior Researcher, Internet Project Lee Rainie, Director, Internet, Science and Technology Research Kathryn Zickuhr, Research Associate, Internet Project Maeve Duggan, Research Analyst, Internet Project Aaron Smith, Senior Researcher, Internet Project

Other reports from the Pew Research Center Internet Project on the topic of privacy and security online can be found at: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/topics/privacy-and-safety/pages/2/

About this survey

The analysis in this report is based on a survey conducted January 10-27, 2014 among a sample of 607 adults, 18 years of age or older. The survey was conducted by the GfK Group using KnowledgePanel, its nationally representative online research panel. GfK selected a representative sample of 1,537 English-speaking panelists to invite to join the subpanel and take the first survey. Of the 935 panelists who responded to the invitation (60.8%), 607 agreed to join the subpanel and subsequently completed the first survey (64.9%). This group has agreed to take four online surveys about “current issues, some of which relate to technology” over the course of a year and possibly participate in one or more 45-60-minute online focus group chat sessions. A random subset of the subpanel receive occasional invitations to participate in these online focus groups. For this report, a total of 26 panelists participated in one of three online focus groups conducted during August 2013 and March 2014. Sampling error for the total sample of 607 respondents is plus or minus 4.6 percentage points at the 95% level of confidence.1

For more information on the GfK Privacy Panel, please see the Methods section at the end of this report.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the generous contributions of the various outside reviewers who offered their insights at various stages of this project. In particular, we would like to thank: Tiffany Barrett, danah boyd, Mary Culnan and all of the attendees of the Future of Privacy Forum Research Seminar Series, Urs Gasser, Chris Hoofnagle, Michael Kaiser, Kirsten Martin and Katie Shilton. In addition, the authors are grateful for the ongoing editorial, methodological and production-related support provided by the staff of the Pew Research Center.

While we greatly appreciate all of these contributions, the authors alone bear responsibility for the presentation of these findings, as well as any omissions or errors.