It makes sense to wonder if the use of digital technology creates stress. There is more information flowing into people’s lives now than ever — much of it distressing and challenging. There are more possibilities for interruptions and distractions. It is easier now to track what friends, frenemies, and foes are doing and to monitor raises and falls in status on a near-constant basis. There is more social pressure to disclose personal information. These technologies are said to takeover people’s lives, creating time and social pressures that put people at risk for the negative physical and psychological health effects that can result from stress.

Stress might come from maintaining a large network of Facebook friends, feeling jealous of their well-documented and well-appointed lives, the demands of replying to text messages, the addictive allure of photos of fantastic crafts on Pinterest, having to keep up with status updates on Twitter, and the “fear of missing out” on activities in the lives of friends and family.9

We add to this debate with a large, representative study of American adults and explore an alternative explanation for the relationship between technology use and stress. We test the possibility that a specific activity, common to many of these technologies, might be linked to stress. It is possible that technology users — especially those who use social media — are more aware of stressful events in the lives of their friends and family. This increased awareness of stressful events in other people’s lives may contribute to the stress people have in their own lives. This study explores the digital-age realities of a phenomenon that is well documented: Knowledge of undesirable events in other’s lives carries a cost — the cost of caring.10

This study explores the relationship between a variety of digital technology uses and psychological stress. We asked people an established measure of stress that is known as the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS).11 The PSS consists of ten questions and measures the degree to which individuals feel that their lives are overloaded, unpredictable and uncontrollable. Participants were asked:

In the last 30 days, how often have you:

- Been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly

- Felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life

- Felt nervous and “stressed”

- Felt confident about your ability to handle any personal problems

- Felt that things were going your way

- Found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do

- Been able to control irritations in your life

- Felt that you were on top of things

- Been angered because of things that were outside of your control

- Felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them

Participants responded on a 4-point scale from “frequently” to “never.” The ten items were combined so that a higher score indicates higher psychological stress (the scale ranges from 0-30 with zero representing no stress and 30 representing the highest level).12

Overall, women experience more stress than men.

The average American adult scored 10.2 out of 30 on the PSS. One of the starkest contrasts in our survey was between the level of reported stress experienced by men and women. On average, women report experiencing significantly higher levels of stress than men. The average women scores 10.5 on the PSS while the average man scores 9.8.13 On average, men reported stress levels that were 7% lower than for women.

There are other demographic characteristics that are related to stress. On average, older adults, and those who are employed tend to have less stress.

How we studied psychological stress and technology use

In the survey, respondents were asked about their use of social networking sites: We asked people about the frequency with which they use different social media platforms, such as Facebook (used by 71% of internet users in this sample), Twitter (used by 18% of internet users), Instagram (17%), Pinterest (21%), and LinkedIn (22%).

Given the popularity of Facebook, we also asked very specific questions about users’ networks and what people do on that platform: number of friends (the average was 329), frequency of status updates (the average was 8 times per month), frequency of “Liking” other people’s content (the average was 34 times per month), frequency of commenting (the average was 22 times per month), and how often they send private messages (the average was 15 times per month).14

We asked people how many digital pictures they share online (the average was 4 times per week), how many people they email (9 people/day), and how many emails they send and receive (an average of 25 per day). We also asked about their use of their mobile phone; the number of messages they text (an average of 32 messages per day), pictures sharing via text (an average of 2 pictures per day), and the number of people that they text with (an average of 4 people per day).

Given the important differences in stress levels based on age, education, marital status, and employment status, we used regression analysis to control for these factors. By using regression analysis we are able determine the degree to which technology use is specifically associated with stress by holding demographic characteristics constant. Since men and women tend to experience stress differently, we ran separate analyses for each sex.

Those who are more educated and those who are married or living with a partner report lower levels of stress.

We found that women, and those with fewer years of education, tend to report higher levels of stress, while those who are married or living with a partner report less psychological stress (see Table 1 in Appendix A). For women (but not men), those who are younger, and those who are employed in paid work outside of the home also tend to experience less stress.

The frequency of internet and social media use has no direct relationship to stress in men. For women, the use of some technologies is tied to lower stress.

For men, there is no relationship between psychological stress and frequent use of social media, mobile phones, or the internet more broadly. Men who use these technologies report similar levels of stress when compared with non-users.

For women, there is evidence that tech use is tied to modestly lower levels of stress. Specifically, the more pictures women share through their mobile phones, the more emails they send and receive, and the more frequently they use Twitter, the lower their reported stress. However, with the exception of Twitter, for the average person, the relationship between stress and these technologies is relatively small. Women who are heavier participants in these activities report less stress. Compared with a woman who does not use these technologies, a women who uses Twitter several times per day, sends or receives 25 emails per day, and shares two digital pictures through her mobile phone per day, scores 21% lower on our stress measure than a woman who does not use these technologies at all.

From this survey we are not able to definitively determine why frequent uses of some technologies are related to lower levels of reported stress for women. Existing studies have found that social sharing of both positive and negative events can be associated with emotional well-being and that women tend to share their emotional experiences with a wider range of people than do men.15 Sharing through email, sending text messages of pictures of events shortly after they happen, and expressing oneself through the small snippets of activity allowed by Twitter, may provide women with a low-demand and easily accessible coping mechanism that is not experienced or taken advantage of by men. It is also possible that the use of these media replaces activities or allows women to reorganize activities that would otherwise be more stressful. Previous Pew Research reports have also documented that social media users also tend to report higher levels of perceived social support. It could be that technology use leads to higher levels of perceived social support, which in turn moderates, or reduces stress, and subsequently reduces people’s risk for the physical diseases and psychological problems that often accompany stress.16

Awareness of Other People’s Stressful Life Events and Social Media Use

This report pays particular attention to social stress. This kind of stress comes from exposure to stressful life events. It is not directly a measure of whether someone feels that their own life is overloaded. Rather, it assesses people’s stress by understanding their social environment.17 Those who experience stressful life events often suffer a range of negative physical outcomes, including physical illness and lower mental health.18

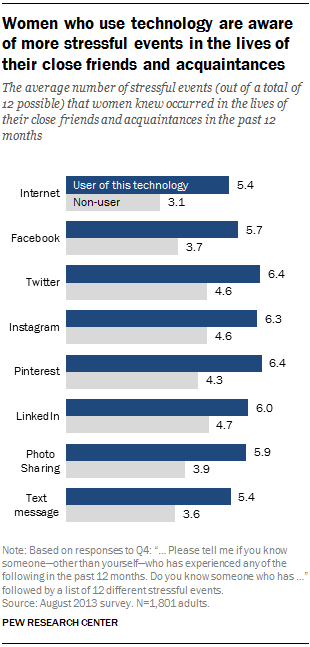

It is possible that technology users — especially those who use social media — are more aware of stressful events in the lives of their friends and family. This increased awareness of stressful events in other people’s lives may contribute to the stress people have in their own lives.

Previous Pew Research reports have documented that social media users tend to perceive higher levels of social support in their networks. They also have a greater awareness of the resources within their network of relationships — on and offline. This awareness has generally been perceived as a social benefit. Individuals who are aware of the things that are happening with their friends and the informal resources available to them through their social ties have more social capital. The extra flows of personal information in social media, what we have termed “pervasive awareness,” are one of the potential benefits of digital technologies.19 However, it is also possible that this heightened awareness comes with a cost.

We wanted to know if the awareness afforded by the use of digital technologies was limited to an awareness of what others could provide (social capital), or if it also included an awareness of the problems and stressful events that take place in the lives of friends, family, and acquaintances. Such awareness is not inherently negative. In fact, an awareness of the problems and hurdles faced by others is a precondition of empathy,20 a dimension of social intelligence (social interest),21 and facilitates the provision of social support. However, awareness can also have an emotional impact – a “cost of caring.”22

To measure awareness of other people’s stress we asked participants if they knew someone – other than themselves – who experienced any of a dozen major life events in the past 12 months. We additionally asked if the person(s) the event happened to was someone close to them (a strong tie), or an acquaintance whom they were not very close with (a weak tie), or both. Our list was composed of major life events that are known sources of stress in people’s lives.23

The survey findings were that in the previous 12 months:

- 57% of adults said they know someone who had started a new job

- 56% know someone who had moved or changed homes

- 54% know someone who had become pregnant, given birth, or adopted a child

- 50% knew someone who had been hospitalized or experienced a serious accident or injury

- 50% knew someone who had become engaged or married

- 42% knew someone who had been fired or laid off

- 36% knew someone who had experienced the death of a child, partner, or spouse

- 36% knew someone who had a child move out of the house or move back into the house

- 31% knew someone who had gone through a marital separation or divorce

- 26% knew someone who had experienced a demotion or pay cut at work

- 22% knew someone who had been accused of or arrested for a crime

- 22% knew someone who had been the victim of a robbery or physical assault

Unsurprisingly, given that most people have few close social ties compared with the number of acquaintances they have, for all of the events we queried, people were more likely to know a weak tie (an acquaintance) than a strong tie who had experienced one of these stressful events.

The average adult in our sample knew people who had experienced 5 of the 12 events that we asked about.

How we studied awareness of stressful events in other people’s lives

As with our analysis of psychological stress, regression analysis was used to test if the use of different digital technologies was related to higher or lower levels of awareness of stressful events in other people’s lives. This allows us to determine the role of different technologies in helping different users be aware of stressful events in others’ lives, controlling for likely differences in awareness that are related to demographic factors such as age, education, race, marital and employment status.

Knowing that the sexes tend to be very different in their awareness of stressful event in the lives of those around them, we further divided our analysis into a comparison of women and men. We also anticipated that some technologies might be more commonly used for communication with close social ties, and primarily provide for an awareness of major events in the lives of close friends and family, while others may be more suited for awareness of events in the lives of looser acquaintances (Appendix A: Table 2).

Women are more aware than men of major events in the lives of people who are close to them.

Previous research has found that women tend to be more aware of the life events of people in their social network than are men.24 When we compared men and women based on the average number of life events that someone in their social network had experienced in the past year, women were consistently more aware than men, although the average was only statistically significant for close relationships.

More educated and younger people are more aware of events in other people’s lives.

A number of demographic factors were consistently related to a higher level of awareness of major events within people’s social networks. For both men and women, those who were younger and those with more years of education tended to know of more major events in the lives of people around them.

In addition, we found that women who were married or living with a partner, and women employed in paid work outside the home, were more aware of events in the lives of their acquaintances (weak ties), but that this was not related to awareness of events in the lives of close friends and family.

Social Media Users Are More Aware of Major Events in the Lives of People Close to Them

Social media use is clearly linked to awareness of major events in other people’s lives. However, the specific technologies that are associated with awareness vary for men and women.

Among both men and women, Pinterest users have a higher level of awareness of events in the lives of close friends and family. The more frequently someone used Pinterest, the more events they were aware of:

- Compared with a woman who does not use Pinterest, a woman who visits Pinterest 18 days per month (average for a female Pinterest user) is typically aware of 8% more major life events from the 12 events we studied amongst her closest social ties.

- Compared with a man who does not use Pinterest, a man who used Pinterest at a similar rate (18 days per month) would tend to be aware of 29% more major life events amongst their closest ties.

Men who used LinkedIn, men who send text messages to a larger number of people, and men who comment on other people’s posts more frequently on Facebook also tend to be more aware of major events in the lives of people close to them. These same technologies had no impact on woman’s awareness of events in the lives of people close to them.

Compared with a man with similar demographic characteristics that does not use the following technologies:

- Those who send text messages to four different people through their mobile phones on an average day (the average for a male cellphone user) tend to be aware of 16% more events amongst those who are close to them.

- A male user of LinkedIn visits the site fifteen times per month and is typically aware of 14% more events in the lives of their closest social ties.

- A male Facebook user, who comments on other Facebook users content 19 times per month, is, on average, aware of 8% more events in the lives of their closest friends and family.

For women, the more friends on their Facebook network and the more pictures they shared online per week, the more aware of major life events in the lives of close friends and family. Compared with demographically similar women who do not use these technologies:

- A woman who shares 4 photos online per week tends to be aware of 7% additional major events in the lives of those who are close to her.

- A female Facebook user with 320 Facebook friends (the average for women in our sample) is, on average, aware of 13% more events in the lives of her closest social ties.

Similarly, men experienced higher levels of awareness as a result of a larger number of different technologies.

Facebook use is associated with more awareness of major events in the lives of acquaintances.

Looking beyond people’s close relationships to include a looser set of their acquaintances, we find that Facebook use is a consistent predictor of awareness of stressful events in others’ lives for both men and women. Specifically, the more Facebook friends people have, and the more frequently they “Like” other people’s content, the more major events they are aware of within their network of contacts.

- Compared with a non-Facebook user, a male Facebook user with 320 Facebook friends is, on average, aware of 6% more major events in the lives of their extended acquaintances. A female Facebook user with the same number of friends is aware of 14% more events in the lives of their weak ties.

- A male or female Facebook user who “Likes” other people’s content about once per day, is typically aware of 10% more major events in the lives of their extended acquaintances.

For women, Instagram is related to lower awareness of major events in the lives of acquaintances, while Twitter and photo sharing are related to higher awareness.

Women are also likely to have higher awareness of their extended network as a result of the number of pictures they share online and through frequent use of Twitter. Compared with a demographically similar woman who does not use these technologies:

- A female Twitter user, who uses the site once per day, tends to be aware of 19% more events in the lives of their extended network.

- A woman who shares 4 digital pictures per week is typically aware of 6% more events in their network of lose social ties.

Use of Instagram was the only technology use that we found to predict lower levels of awareness, and only for women. This might be the case because Instagram is used differently that some other kinds of social media. Scholars have found that many people make cellphone calls and exchange text messages predominantly with their closest ties. They have argued that this is “tele-cocooning,”25and they believe that people’s use of mobile phones leads to contact with more intimate relations at the expense of weaker and more diverse social ties. Instagram use may be tied to a similar pattern. Those who use Instagram might reduce their focus on the lives of their social ties that are not considered especially close. Controlling for other factors, a female user of Instagram who uses the platform a few times per day is, on average, aware of 62% fewer major events in the lives of their extended network than someone who does not use Instagram at all.

For men, text messaging, email, and Pinterest are related to higher awareness of major events in the lives of acquaintances.

In addition to use of Facebook, men’s awareness of stressful events in their friends’ lives tends to be higher for those who email and send text messages to a larger number of people. Compared with someone who does not use these technologies:

- A male email user who is in contact with 9 different people by email per day is generally aware of 13% more events in the lives of their distant social circle.

- A male who sends text messages to four people per day is, on average, aware of 11% more major events in the lives of their weaker social ties.