An elaboration of the findings in the AAAS member survey

Scientific innovations are deeply embedded in national life — in the economy, in core policy choices about how people care for themselves and use the resources around them, and in the topmost reaches of Americans’ imaginations. New Pew Research Center surveys of citizens and a representative sample of scientists connected to the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) show powerful crosscurrents that both recognize the achievements of scientists and expose stark fissures between scientists and citizens on a range of science, engineering and technology issues. This report highlights these major findings:

Science holds an esteemed place among citizens and professionals. Americans recognize the accomplishments of scientists in key fields and, despite considerable dispute about the role of government in other realms, there is broad public support for government investment in scientific research.

The key data:

- 79% of adults say that science has made life easier for most people and a majority is positive about science’s impact on the quality of health care, food and the environment.

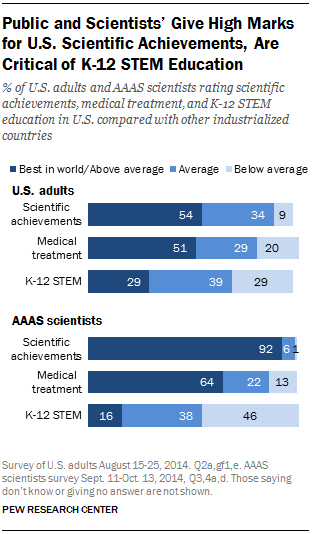

- 54% of adults consider U.S. scientific achievements to be either the best in the world (15%) or above average (39%) compared with other industrial countries.

- 92% of AAAS scientists say scientific achievements in the U.S. are the best in the world (45%) or above average (47%).

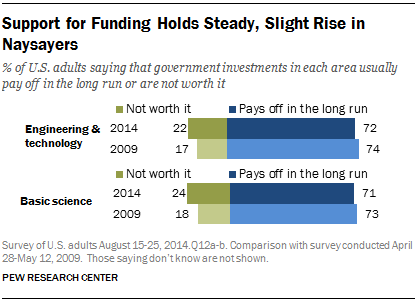

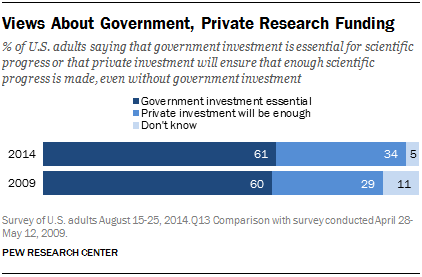

- About seven-in-ten adults say that government investments in engineering and technology (72%) and in basic scientific research (71%) usually pay off in the long run. Some 61% say that government investment is essential for scientific progress, while 34% say private investment is enough to ensure scientific progress is made.

At the same time, both the public and scientists are critical of the quality of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM subjects) in grades K-12.

The key data:

- Only 16% of AAAS scientists and 29% of the general public rank U.S. STEM education for grades K-12 as above average or the best in the world. Fully 46% of AAAS scientists and 29% of the public rank K-12 STEM as “below average.”

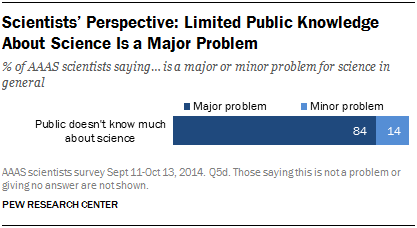

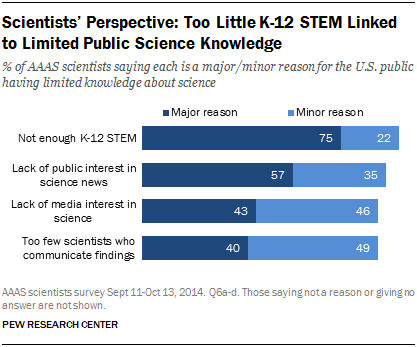

- 75% of AAAS scientists say too little STEM education for grades K-12 is a major factor in the public’s limited knowledge about science. An overwhelming majority of scientists see the public’s limited scientific knowledge as a problem for science.

Despite broadly similar views about the overall place of science in America, citizens and scientists often see science-related issues through different sets of eyes. There are large differences in their views across a host of issues.

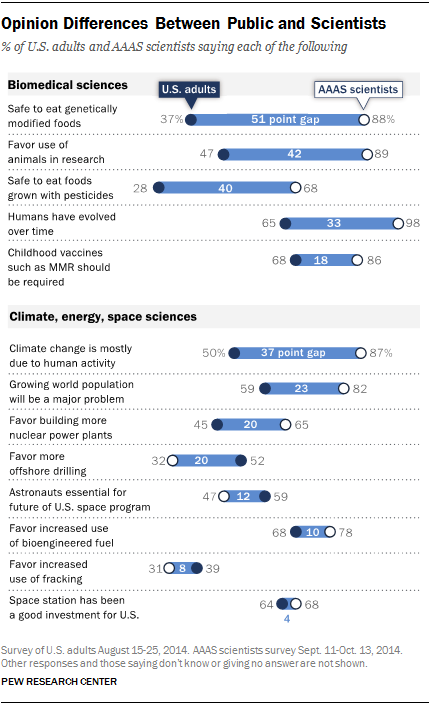

The key data:

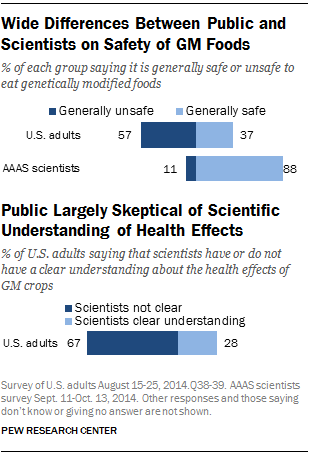

- A majority of the general public (57%) says that genetically modified (GM) foods are generally unsafe to eat, while 37% says such foods are safe; by contrast, 88% of AAAS scientists say GM foods are generally safe. The gap between citizens and scientists in seeing GM foods as safe is 51 percentage points. This is the largest opinion difference between the public and scientists.

- Citizens are closely divided over animal research: 47% favor and 50% oppose the use of animals in scientific research.1 By contrast, an overwhelming majority of scientists (89%) favor animal research. The difference in the share favoring such research is 42 percentage points.

- In some areas, like energy, the differences between the groups do not follow a single direction — they can vary depending on the specific issue. For example, 52% of citizens favor allowing more offshore drilling, while fewer AAAS scientists (32%), by comparison, favor increased drilling. The gap in support of offshore drilling is 20 percentage points. But when it comes to nuclear power, the gap runs in the opposite direction. Forty-five percent of citizens favor building more nuclear power plants, while 65% of AAAS scientists favor this idea.

- The only one of 13 issues compared where the differences between the two groups are especially modest is the space station. Fully 64% of the public and 68% of AAAS scientists say that the space station has been a good investment for the country; a difference of four percentage points.

Compared with five years ago, both citizens and scientists are less upbeat about the scientific enterprise. Citizens are still broadly positive about the place of U.S. scientific achievements and its impact on society, but slightly more are negative than five years ago. And, while a majority of scientists think it is a good time for science, they are less upbeat than they were five years ago. Most scientists believe that policy regulations on land use and clean air and water are not often guided by the best science.

The key data:

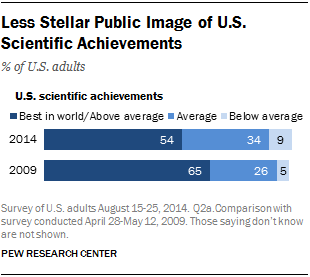

- While a majority of the public sees U.S. scientific achievements in positive terms, the share saying U.S. scientific achievements are the best in the world or above average is down 11 points to 54% today, compared with 65% in 2009.

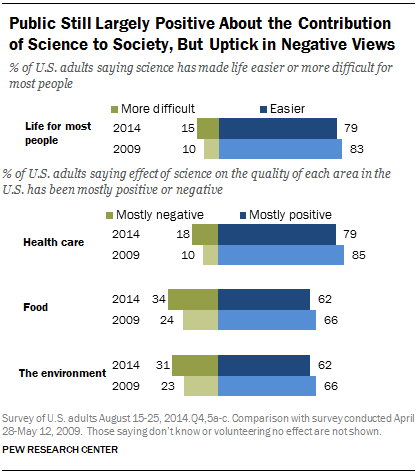

- 79% of citizens say that science has made life easier for most people, while just 15% say it has made life more difficult. However, the balance of opinion is slightly less positive today than in 2009 when positive views outpaced negative ones by a margin of 83% to 10%. A similar pattern is found in views about the effect of science on the quality of health care, food, and the environment. In each case, while most adults see a positive effect of science, there is a slight rise in the share expressing negative views.

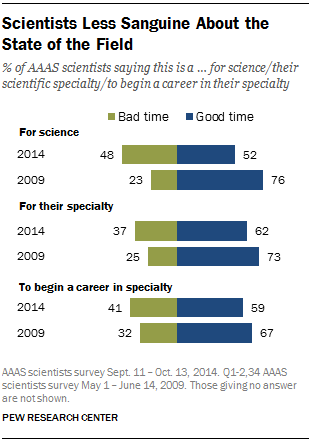

- 52% of AAAS scientists say this is generally a good time for science, down 24 percentage points from 76% in 2009. Similarly, the share of scientists who say this is generally a good time for their scientific specialty is down from 73% in 2009 to 62% today. And, the share of AAAS scientists saying that this is a good or very good time to begin a career in their field now stands at 59%, down from 67% in 2009.

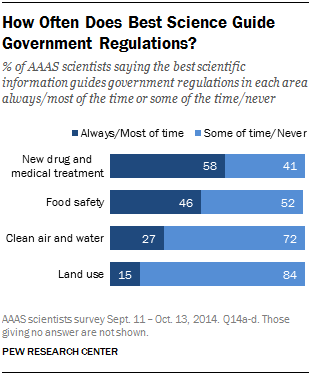

- Only 15% of scientists say they believe policy choices about land use are guided by the best science most of the time or always; 27% think the best science frequently guides regulations about clean air and water; 46% think the best science is frequently used in food safety regulations and 58% say the same when it comes to regulations about new drug and medical treatments.

These are some of the findings from a new pair of surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center in collaboration with the AAAS. The survey of the general public was conducted by landline and cellular telephone August 15-25, 2014 with a representative sample of 2,002 adults nationwide. The margin of sampling error for results based on all adults is plus or minus 3.1 percentage points. The survey of scientists is based on a representative sample of 3,748 U.S.-based members of AAAS; the survey was conducted online from Sept. 11 to Oct. 13, 2014.2

A Sizable Opinion Gap Exists Between the General Public and Scientists on a Range of Science and Technology Topics

Citizens’ and scientists’ views diverge sharply across a range of science, engineering and technology topics. Opinion differences occur on all 13 issues where a direct comparison is available. A difference of less than 10 percentage points occurs on only two of the 13.

The largest differences between the public and the AAAS scientists are found in beliefs about the safety of eating genetically modified (GM) foods. Nearly nine-in-ten (88%) scientists say it is generally safe to eat GM foods compared with 37% of the general public, a difference of 51 percentage points. One possible reason for the gap: when it comes to GM crops, two-thirds of the public (67%) say scientists do not have a clear understanding about the health effects.

Chapter 3 looks at public and scientists’ attitudes on each of these issues in more detail along with several topics asked only of the general public, including access to experimental medical treatments, bioengineering and genetic modifications.

Both the Public and Scientists See U.S. Scientific Achievements in a Positive Light. But They Are Critical of K-12 STEM Education.

Despite differences in views about a range of biomedical and physical science topics, both the public and scientists give relatively high marks to the nation’s scientific achievements and give distinctly lower marks to K-12 education in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (known as STEM). Just 16% of AAAS scientists and 29% of adults in the general public considers K-12 STEM education in the U.S. to be the best or above average compared with other industrialized countries. Both groups see U.S. scientific achievements and medical treatment in a more positive light, by comparison.

About half of Americans (54%) consider U.S. scientific achievements to be above average or among the best in the world. The only aspect of American society rated more favorably is the U.S. military system (77%). About half (51%) also see U.S. medical treatment as in the top tier compared with other industrialized countries. Public views about K-12 STEM are markedly more negative: 29% say it is the best or above average, while 39% say it is average and another 29% say it is below average. (For more on public assessments of key institutions and industries, including the economy, health care, and the political system see Chapter 2.)

Compared with the general public, scientists are even more positive about the place of U.S. scientific achievements. Fully nine-in-ten (92%) AAAS scientists consider scientific achievements in the U.S. to be the best in the world (45%) or above average (47%).

Scientists also have largely positive views about the global standing of U.S. medical treatment (64% say it is the best in the world or above average) as well as other aspects of science and technology including doctoral training (87%), cutting edge basic research (87%) and industry research and development innovation (81%). Just 16% of scientists say the same about K-12 STEM.

Among scientists, the public’s knowledge about science — or lack thereof — is widely considered to be a major (84%) or minor (14%) problem for the field.

And when asked about four possible reasons for the public having limited science knowledge, three-quarters of AAAS scientists in the new survey say too little K-12 STEM education is a major factor.

Citizens Are Still Broadly Positive About the Achievements of American Science and Its Impact on Society, But Slightly More Are Negative than Five Years Ago. Scientists Are Also Still Largely Positive, But Less Upbeat than Five Years Ago.

A number of the questions asked in these new surveys repeat questions that Pew Research Center asked citizens and scientists in 2009. In key areas, both the public and AAAS scientists are less upbeat today.

Among the public, perceptions of the scientific enterprise and its contribution to society, while still largely positive, are a little less rosy than five years ago. Fewer citizens see U.S. scientific contributions as top tier compared with other nations. And, while most adults see positive contributions of science on life overall and on the quality of health care, food and the environment, there is a slight rise in negative views in each area. Similarly, most citizens say government investment in research pays off in the long run, but slightly more are skeptical about the benefits of government spending today than in 2009. While the change is modest on several of these measures, the share expressing negative views on each is slightly larger today than in 2009.3

Scientists’ views have moved in the same direction. Though scientists hold mostly positive assessments of the state of science and their scientific specialty today, they are less sanguine than they were in 2009 when Pew Research conducted a previous survey of AAAS members. The downturn is shared widely among AAAS scientists regardless of discipline and employment sector.

Perception of U.S. Scientific Achievements

Overall, 54% of adults consider U.S. scientific achievements to be either the best in the world (15%) or above average (39%) compared with other industrial countries. Of the seven aspects of American society rated, only one was seen more favorably: the U.S. military. Compared with 2009, however, the share saying that U.S. scientific achievements are the best in the world or above average is down 11 points, from 65% in 2009 to 54% today. More now see U.S. scientific achievements as “average” in the global context (up from 26% in 2009 to 34% today) or “below average” (up slightly from 5% in 2009 to 9% today). Perceptions of some other key sectors, including U.S. health care, also dropped during this timeframe. See Chapter 2 for details.

Partisan groups tend to hold similar views of U.S. scientific achievements and, the drop in ratings of U.S. scientific achievements since 2009 has occurred across the political spectrum.

When it comes to policy prescriptions, however, a partisan divide emerges. A separate Pew Research Center report released this month finds that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to prioritize “supporting scientific research” for the President and the Congress in the coming year. Younger adults are also more likely than their elders to say supporting scientific research should be a top priority for the President and the new Congress.4

Effects of Science on Society

Overall the American public tends to see the effects of science on society in a positive light. Fully 79% of citizens say that science has made life easier for most people, while just 15% say it has made life more difficult. However, the balance of opinion is slightly less positive today than in 2009 when positive views outpaced negative ones by a margin of 83% to 10%.

Similarly, a majority of adults says the effect of science on the quality of U.S. health care, food and the environment is mostly positive as was also the case in 2009. The share saying that science has had a negative effect in each area has increased slightly. For example, 79% of adults say that science has had a positive effect on the quality of health care, down from 85% in 2009 while negative views have ticked up from 10% in 2009 to 18% today.

Perceived Contributions of Scientists, Engineers, and Medical Doctors to Society

A 2013 Pew Research report found the military at the top of the list of 10 occupational groups seen as contributing “a lot” to society (78%), followed by teachers (72%), medical doctors (66%), scientists (65%) and engineers (63%). The order of ratings for each of the 10 groups was roughly the same in 2013 as in 2009, though there were modest declines in public appreciation for several occupations.

Public appreciation of scientists’ contribution dropped 5 points from 70% in 2009 to 65% in 2013 with a corresponding uptick to 8% in those saying scientists contribute “not very much” or “nothing at all” compared with 5% in 2009. Views of medical doctors’ contribution fell 3 points from 69% in 2009 to 66% in 2013. Those of engineers stayed about the same (64% in 2009 and 63% in 2013).

Adults under age 50 and college graduates tended to be more upbeat in their assessments of scientists, engineers and medical doctors. Partisan and ideological differences were found in views about the contribution of scientists and engineers but not in views about medical doctors. For details see “Public Esteem for Military Still High,” July 11, 2013.

When it comes to food, 62% of Americans say science has had a mostly positive effect, while 34% say science has mostly had a negative effect on the quality of food. The balance of opinion is a bit less rosy on this issue compared with 2009 when positive views outstripped negative ones by a margin of 66% to 24%.

Similarly, more say science has had a positive (62%) than negative (31%) effect on the quality of the environment today. But, the balance of opinion on this issue has shifted somewhat compared with 2009 when 66% said science had a positive effect and 23% said it had a negative effect.

These modest changes over time have occurred among both Republicans (including independents who lean Republican) as well as Democrats (including independents who lean Democratic). However, Republicans’ views about the effect of science on health care and food have changed more than those of Democrats.

Both Republicans and Democrats have shifted by about the same amount in their assessment of science’s effect on the quality of the environment; there are no significant differences by party affiliation when it comes to the overall effect of science on the environment. Two-thirds (66%) of Republicans and independents who lean to the Republican Party say the effect of science on the quality of the environment in the U.S. has been mostly positive, as do 61% of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party. (A detailed look at attitudes about science and technology topics by political groups is forthcoming later this year).

Public Support for Research Funding Since 2009

A majority of the public sees societal benefit from government investment in science and engineering research. Roughly seven-in-ten adults say that government investment in engineering and technology (72%) as well as basic science research (71%) pays off in the long run while a minority says such spending is not worth it (22% and 24%, respectively). Positive views about the value of government investment in each area is about the same as in 2009, though negative views that such spending is not worth it have ticked up 5 points for engineering and technology research and 6 points for basic science research.

Views about the role of government funding as compared with private investment show steady support for government investment (61% in 2014 and 60% in 2009) but, there is a slight rise in the view that private investment, without government funds, will be enough to ensure scientific progress (from 29% in 2009 to 34% today). The modest difference over time stems from more expressing an opinion today than did so five years ago.

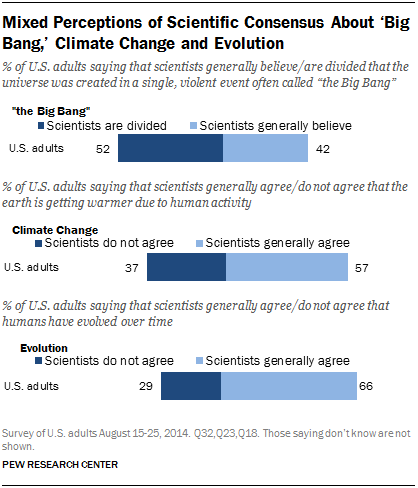

Mixed Perceptions About the Degree of Scientific Consensus

The general public tends to hold mixed views about the degree to which they believe there is scientific consensus on three hot-button science topics — the “Big Bang” theory, climate change and evolution.

Asked whether scientists generally believe that the universe was created in a single violent event often called “the Big Bang,” about four-in-ten (42%) say yes while about half (52%) say scientists are generally divided about this issue.

When it comes to climate change and evolution, a majority of adults see scientists as generally in agreement that the earth is getting warmer due to human activity (57%) or that humans have evolved over time (66%), though a sizeable minority see scientists as divided over each. Perceptions of where the scientific community stands on both climate change and evolution tend to be associated with individual views on the issue.

Scientists Are Still Largely Positive, But Are Less Upbeat About the State of Science Today Than They Were Five Years Ago.

Scientists’ overall assessments of the field, while still mostly positive, are less upbeat than they were in 2009 when Pew Research conducted a previous survey of AAAS members.

Today, about half of AAAS scientists (52%) say this is good time for science, down 24 percentage points from three-quarters (76%) in 2009.

Scientists are more positive, by comparison, when it comes to the state of their scientific specialty. But here, too, scientists are less rosy in their assessments than five years ago: 62% of AAAS scientists say this is a good time for their specialty area, down 11 percentage points from 2009.

These more downbeat assessments occur among AAAS scientists across all disciplines, among those with both a basic and applied research focus,5 and across all employer types.

Some 59% of AAAS scientists say this is a good or very good time to begin a career in their specialty, down from 67% in 2009. Assessments about the state of their specialty for new entrants is about the same as 2009 for those focused on applied research (71% in 2009 and 69% today say it a good or very good time), but it is down 15 percentage points among those doing basic research, from 63% in 2009 to 48% today saying this is a good or very good time to begin a career in their specialty area.

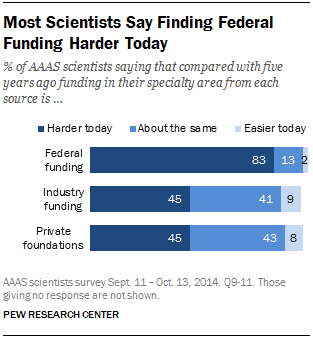

There are a number of possible reasons for scientists’ less optimistic assessments over this period including the different economic and political contexts,6 heightened concerns among scientists about the research funding environment, and, perhaps, what scientists see as the limited impact their work is having on policy regulations.

Fully 83% of AAAS scientists report that obtaining federal research funding is harder today than it was five years ago. More than four-in-ten say the same about industry funding (45%) and private foundation funding (45%) compared with five years ago. Further, when asked to consider each of seven potential issues as a “serious problem for conducting high quality research today,” fully 88% of AAAS scientists say that a lack of funding for basic research is a serious problem, substantially more than any of the other issues considered.7

Scientists have, at best, mixed views about the impact of the research enterprise on four areas of government regulations. A majority of AAAS scientists (58%) say that the best scientific information guides government regulations about new drug and medical treatments at least most of the time, while about four-in-ten (41%) say such information guides regulations only some of the time or never. Views about the impact of scientific information on food safety regulations are more mixed with 46% saying the best information guides regulations always or most of the time and a slightly larger share (52%) saying it does so only some of the time or never. Scientists are largely pessimistic that the best information guides regulations when it comes to clean air and water regulations or land use regulations: 72% and 84%, respectively, say this occurs only some of the time or never.

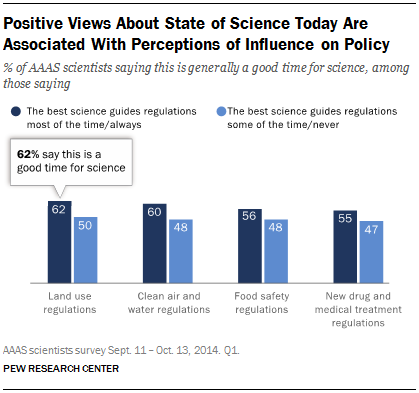

Scientists’ views about the impact of research on government regulations in each domain tend to be associated with their views about the state of the overall science environment.

For example, those who see a more frequent impact of scientific findings on land use regulations also tend to be more upbeat about the state of science today; 62% say this is generally a good time for science. By comparison, those who say the best science guides land use regulations only some of the time or never are less positive. Half (50%) of this group says it is a good time and an equal share says it is a bad time for science overall. The same pattern holds for each of the four types of regulations considered in the survey. Scientists who perceive a more frequent influence of the best science on regulations are also more likely to say this is a good time for science compared with scientists who see less frequent impact of the best scientific information on policy rules.

Roadmap to the report

What is the AAAS?

The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) is the world’s largest general scientific society, and as such, encompasses all disciplines in the scientific community. Founded in 1848, AAAS publishes Science, one of the most widely-circulated peer-reviewed scientific journals in the world. It is an international non-profit organization whose mission is broadly defined as seeking to “advance science, engineering, and innovation throughout the world for the benefit of all people.”

The remainder of this report details the findings on both public and scientists’ views about science, engineering and technology topics. Chapter 1 briefly outlines related Pew Research Center studies and reviews some of the key caveats and concerns in conducting research in this area. Chapter 2 looks at overall views about science and society, the image of the U.S. as a global leader, perceived contributions of science to society, and views about government funding for scientific research. Chapter 3 covers attitudes and beliefs about a range of biomedical and physical science topics. It focuses on comparisons between the public and AAAS scientists and also covers public attitudes on access to experimental drugs, bioengineering of artificial organs, genetic modifications and perceptions of scientific consensus. Chapter 4 examines the views of AAAS scientists about the scientific enterprise, issues and concerns facing the scientific community, and issues for those newly entering careers in science. It also includes the experiences and background characteristics of the AAAS scientists in the survey. Appendices provide a detailed report on the methodology used in each survey as well as the full question wording and frequency results for each question in this report.

About This Report

This report is based on a pair of surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center in collaboration with the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). It looks at the views of the general public and scientists about the place of science in American culture, their views about major science-related issues, and the role of science in public policy.

This is the first of several reports analyzing the data from this pair of surveys. This report focuses on a comparison of the views of the general public and those of AAAS scientists as a whole. Follow up reports planned for later this year will analyze views of the general public in more detail, especially by demographic, religious, and political subgroups. And, some results from the survey of AAAS scientists will be presented in a follow-up report in mid-February.

The fieldwork for both surveys was conducted by Princeton Survey Research Associates International. Contact with AAAS members invited to participate in the survey was managed by AAAS staff with the help of Princeton Survey Research Associates International; AAAS also covered part of the costs associated with mailing members. All other costs of conducting the pair of surveys were covered by the Pew Research Center. Pew Research bears all responsibility for the content, design and analysis of both the AAAS member survey and the survey of the general public.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Jeanne Braha and Tiffany Lohwater of AAAS who facilitated the interactions between Pew Research and AAAS staff to conduct the survey of members and to Ian King, director of marketing at AAAS, as well as Elizabeth Sattler and Julianne Wielga, who prepared the random sample of members and sent out all contacts with AAAS members selected for participation. We are also grateful to the team at Princeton Survey Research International who led the data collection efforts for the two surveys.