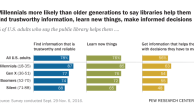

Many see libraries as places of learning and pursuing knowledge. Pew Research Center’s April 2015 survey explored those themes and took an expansive view by asking people how they see libraries as vehicles for economic opportunity and inclusion of various groups that have drawn particular attention from librarians. This scope of inquiry provides insight into how the public sees the library not just as an institution that has a history in their community, but also whether they see libraries as places that might serve groups particularly affected by technological or other cultural changes.

The nearby chart summarizes how Americans ages 16 and older think about changes libraries should consider going forward. The survey asked people to consider “some new things public libraries could do to change how they serve the public.” Here is what they said:

The remainder of this chapter addresses various themes that flow from these views of the public.

Libraries and education

Overwhelming majorities of Americans see education as the foundation of libraries’ mission. Some 85% think that coordinating more closely with local schools in providing resources to children is something libraries should “definitely” do. This is unchanged from a 2012 Pew Research survey. The same share of those ages 16 and older (85%) say that libraries should “definitely” offer free early literacy programs to help prepare kids for school, up slightly from 82% who said this in 2012.

Additionally, 78% think the libraries in their communities are effective in promoting literacy and love of reading among people. Some 36% say libraries are “very effective” at this and 42% say they are “somewhat effective.” Hispanics and blacks (48% and 41% respectively) are more likely than others to say libraries are very effective at promoting literacy and love of reading.

When people go to the library, many do so explicitly for educational advancement. Among those who went to the library in the last 12 months and used library computers, the internet or Wi-Fi, 60% have used those tools to do research for school or work, and 17% have used them for taking an online class or completing an online certification. In addition, 17% did so to attend a class or lecture.

People’s views about libraries and education are not just about schools and basic literacy. Strong majorities of Americans believe libraries have a role in information literacy, with two-thirds (65%) agreeing with the proposition that libraries contribute to helping people decide whether they can trust information – 24% agreed with this “a lot” and 41% agreed “somewhat.” Lower income and less educated Americans are more likely to agree “a lot” that libraries contribute to people’s calculations of trustworthy information; 31% of high school graduates and 30% of those whose annual incomes fall below $30,000 say this. Additionally, 33% of Hispanics say libraries help “a lot” in helping people decide which information warrants trust.

Libraries as providers of resources for immigrants and veterans – and for those who want technology help

People see libraries as more than places to enhance educational and economic opportunities. They also see libraries as important parts of the community fabric in other ways that serve key groups in the community and help those who are not yet fully literate about technology.

The community dimension of inclusion is captured in attitudes about veterans and immigrants. Three-quarters (74%) of all Americans ages 16+ say that creating programs or services for active military personnel or veterans is something libraries should “definitely” do. Furthermore, a strong majority (59%) say that libraries should “definitely” create services or programs for immigrants or first-generation Americans – a larger share than the 52% who say this about programs for local businesses or entrepreneurs. Hispanics are far more likely to say libraries should create programs for immigrants or first generation Americans – 78% do.

As to how Americans value what libraries bring to their communities, 68% of those ages 16 and older say that libraries help people learn about local events and resources in their community; 29% say libraries help “a lot” with this and 39% say they help “somewhat.” Similarly, 63% say libraries help people find out about volunteer activities and other ways people can contribute to their community. About a quarter (24%) say libraries help “a lot” in this regard, while 39% say libraries help “somewhat.”

Beyond technology access, people see libraries as places where they can cultivate digital skills. Some 70% say libraries help people learn how to use new technologies (31% say they help “a lot” and 39% say “somewhat”). More high school graduates (39%) and lower-income households (38% for those in households whose annual income falls below $30,000) say libraries help “a lot” in helping people learn new technologies. And a very strong majority of all Americans – 76% – say that libraries should “definitely” offer programs to teach people how to protect their privacy and security online.

Even though people strongly believe in the role of libraries in digital inclusion, relatively few library users actually used libraries for this purpose. Just 7% say they had taken a class on how to use the internet or computers when asked about their use of the library in the past 12 months.

In a similar vein, a modest number of online users also turn to libraries for help with digital applications that pertain to institutions they encounter – such as government, banks, schools or other businesses.

For the most part, online users find that engaging with these institutions through the internet or email is easy: 82% say this, with 42% saying it is “very” easy to do this and 40% saying it is “somewhat” easy. When probed about the ease of performing tasks with these institutions through mobile apps, two-thirds say it is easy, with 29% saying it is “very” easy and 37% saying it is “somewhat” easy. To the extent that people do encounter challenges in using these applications – either through email, a web browser on their computer or mobile device – 14% say they have turned to the public library for help on how to carry out tasks.

Libraries, economic opportunity and workforce skills

With the nation still coping with the aftereffects of a severe economic downturn that began around 2007, jobs and business creation remain top of mind for many Americans. The upshot is that roughly half (52%) of all Americans says that public libraries should “definitely” create services or programs for local businesses and entrepreneurs. Hispanics and blacks are more likely to see the value of such programs, as 60% of each think libraries should “definitely” have them.

Additionally, 45% say that purchasing 3-D printers or other digital tools is something libraries should “definitely” do and 35% say it is something libraries should “maybe” consider doing. There is not as much public support for these activities as for others on our list. Some segments of the population are more enthusiastic than others. Those on the lower end of the socio-economic scale are more likely to say libraries should “definitely” invest in these new digital tools. Some 57% of high school graduates say libraries should do this, as do 54% in households with an annual income below $30,000 per year. Additionally, 59% of blacks and 56% of Hispanics think libraries should “definitely” purchase 3-D printers or other digital tools.

People’s use of the library to improve their economic prospects ranges across a variety of different topics, with no single one dominating. Job seeking is the most prevalent activity. Among those who have used a public library’s computers, internet or Wi-Fi connection in the past 12 months, 23% had used one of those things to look for or apply for a job. That is down significantly from 2012, when more than one-third (36%) did so. This change likely reflects the sharp drop in the unemployment rate over that timeframe. The U.S. unemployment rate was 7.7% in November 2012 compared to the 5.4% figure for April 2015.

Building job skills was another theme for library users. Focusing on those who had visited a public library in-person the prior year:

- 14% sought to acquire job-related skills in order to increase their income.

- 9% wanted to learn how to start or expand their own business.

- 9% went to the library to use a 3-D printer or other high-tech device – something related to creativity and self-expression as well as job skills.

Finally, among those who visited a public library in-person in the prior 12 months, 15% had done so in order to search for or apply for a job.

Libraries as centers of civic collaboration

As library usage patterns have unfolded over the past several years, the library’s role as an anchor of civic activity has earned particular attention among advocates and some library leaders. In this survey, we asked about civic activity in two ways. First, we queried whether someone, in the past year, has worked with fellow citizens to solve a community problem. Second, we asked whether respondents had been an active member of a group trying to influence government or public policy in the past 12 months (this excludes activities connected to political parties).

Nearly one-quarter of those ages 16 and over, in the past year, worked with fellow citizens to tackle a problem in their community – 23% say they had. Among this group, 63% visited a library or bookmobile in person in the past year and 33% had used the library’s website. For those who have not had such collaborations with fellow citizens, 40% visited a library or bookmobile in-person in the past year and only 19% had used a library’s website.

A smaller number – 11% – of Americans 16 and older have been an active member of a group seeking to influence government or policy. Among those, 59% have visited a public library or bookmobile in-person in the past year and 39% have used the library’s website. For those not active in such groups, 44% visited a library or bookmobile in the past year and 20% used a library website.

Although the survey did not directly ask whether some of these civic activities took place at the library, there are indications that this happened at least occasionally. Among those who were active in a group trying to influence government or a policy issue, 33% attended a meeting in person of a group to which they belong at a library in the past year. Just 13% of those who were not part of an effort to influence government or policy attended a meeting in person at the library during that time. Similarly, 28% of those who had worked with other community members to address a problem attended a meeting at the library in the past year, compared with 11% of those who did not collaborate with others to address a community problem.