During President Obama’s first full day in office on Jan. 21, 2009, he issued a statement committing his administration to pursue “an unprecedented level of openness in Government.” His goal was to make the federal government more transparent, participatory and collaborative through the use of new technologies.

The broader effort was called the Open Government Initiative, and a key part of it took effect more than two years later when the administration created an online petitioning system called “We the People” in September 2011. The White House promised to use the site to engage with the public and to issue responses to all petitions that reached a given number of signatures within 30 days of creation. The original threshold was set at 5,000 signatures but was increased to 100,000 in later years. As Obama prepares to leave office in early 2017, the site has been active for more than five years and is one of the most prominent legacies of the open government initiative.

In order to understand how citizens used the opportunity to directly seek redress from the White House, and how the administration responded, Pew Research Center conducted a detailed content analysis of “We the People” petitions. The “We the People” archive includes all petitions that received at least 150 signatures within the first 30 days of when they were posted on the site.1 The Center downloaded and examined these petitions covering the period from the site’s 2011 inception through July 3, 2016. The analysis is based on a combination of publicly available data provided by the site’s API and human coding of all 4,799 publicly available petitions and 227 White House responses.

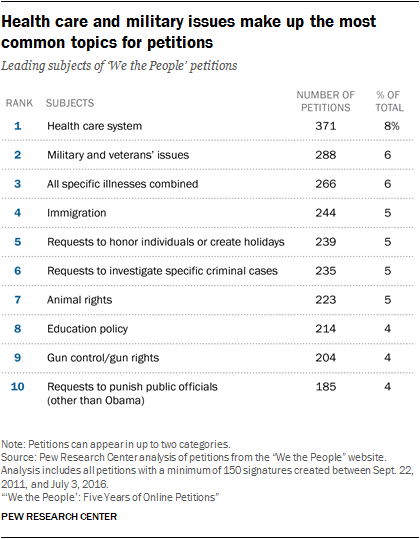

This analysis shows that no one type of request dominated the online petition system, with users of the site instead addressing a wide range of topics. The topmost subjects included petitions pertaining to the health care system (8%); disease awareness and related issues (6%); veterans’ and military issues (6%); immigration (5%); requests to honor individuals or create holidays (5%); requests to investigate criminal cases (5%); and animal rights (5%).

In terms of whether these petitions had any impact, the study suggests there were a variety of outcomes:

- At the most meaningful level, one petition was instrumental in creating a significant piece of legislation: A January 2013 petition regarding the unlocking of cellphones led to a bill that Obama signed into law in August 2014. The petition called for making it illegal for telephone companies to “lock” their phones by preventing a phone purchased from one telephone carrier to be used on another carrier’s system.

- Another petition was important in changing President Obama’s position on state laws banning “conversion therapy.” After a 2015 petition sought to encourage states to bar the controversial therapies that try to “convert” lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer Americans (LGBTQ+) to heterosexual, the White House says that the president decided to support state laws banning these therapies.

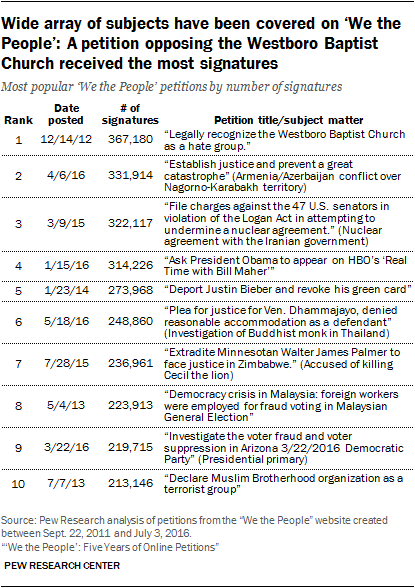

- A January 2016 petition requesting the president make an appearance on a previously unvisited late night talk show – the fourth most signed petition on the site – was a major reason Obama appeared on HBO’s “Real Time with Bill Maher” a few days before the 2016 presidential election.

- One petition helped convince Obama to give the Medal of Freedom to baseball Hall of Famer Yogi Berra. And the president met with some active users of the site in July 2015. He and Michelle Obama also hosted a special meeting for 106-year-old petitioner Virginia McLaurin.

Beyond that, it is difficult to calculate the impact of the site, as not all the inner workings of the White House are made public. It is certainly possible that other petitions may have raised awareness about some issues and over the five year time period some petitions drew press coverage to their subjects or petitioners.

Some other notable trends in the data about “We the People”:

Several of the most popular petitions focused on small groups or international issues that did not necessarily gain much media attention or fall in the purview of the federal government. The single-most popular petition – with 367,180 signatures – was a request to recognize the Westboro Baptist Church as a hate group. Church members regularly picket the burial services for U.S. service personnel and confront people with anti-gay slogans. The second-most popular involved a conflict over disputed territory between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The first days of the site were among the most active periods in its history. Only one other time period – beginning in late 2012 – featured more activity than the opening days. During the site’s first eight days, users created 174 petitions that received enough attention to be archived. Some 31 petitions created on the site’s first day reached the original signature threshold to receive a White House response, including a request to remove “In God We Trust” from all currency. Throughout the rest of the site’s existence, there were only three calendar months that had more petitions than those first eight days: the three consecutive months starting in November 2012, during which the site averaged 268 petitions per month in the wake of Obama’s reelection.

Increases in signature thresholds led to a major decline in the share of petitions meeting the requirement to receive a formal response. In the first 12 days of the site’s existence in 2011, any petition receiving 5,000 signatures from the public was guaranteed a White House response – and 44% of archived petitions submitted during that time met this requirement. The White House quickly raised the threshold to 25,000 signatures and at that level just 9% of petitions met the condition. In mid-January 2013, the threshold was raised once more to 100,000 signatures and only 2% of petitions from that time onward have met the threshold.

Requests to honor individuals or investigate criminal cases were common. In total, 239 petitions requested the White House honor a person or create a holiday (5%), while 235 petitions asked to investigate criminal cases (also 5%). Among the most popular requests for holiday commemorations included the Muslim holidays of Eid al-Fitr and Eid al-Adha, the Lunar New Year and Halloween.

Users saw the site as a chance to defend the rights of American citizens. One of the features of the site was that it allowed petition creators to use up to three “tags” (out of a list of about 20 options) to categorize their requests. Nearly half of petitions (48%) were tagged as pertaining to “human rights” or “civil rights” by the authors, far and away the most prevalent labels applied by petitioners. Other common tags included those tied to criminal justice reform (listed on 16% of the petitions), foreign policy (14%), family (12%), health care (12%), economy and jobs (12%), and government reform (12%).

While most of the early responses were written by relatively prominent members of the government, over time, the White House increasingly relied on anonymous authorship. In 2012, 95% of the White House responses had a named author. By 2015, that figure had fallen to 8% – and many official responses were simply credited to the “The ‘We the People’ Team.”

The White House’s response time grew longer during the site’s first two years. However, wait times began to shrink in 2014. For petitions created in 2011 that reached the signature threshold, the average time to receive a White House response was 133 days. By 2013, the average was up to 271 days. In the first half of 2016, however, the average response time was down to 34 days.

Users of the site created a number of petitions focused on off-beat topics not likely to be taken seriously by the White House or the public. Some of the unusual requests included a petition to recognize International Talk Like a Pirate Day and an effort to change the national anthem to the My Little Pony theme song called “Friendship is Magic.”