People seeking employment must increasingly put their “best foot forward” not just to a hiring manager, but to a computer program with power to weed them out or deliver them to the next step of the process. The use of artificial intelligence in hiring is commonplace and can take a number of forms, from screening applicants to conducting interviews. But increasing use of AI by employers has led some to question the fairness, quality and accuracy of hiring decisions made in this way – even as others tout AI as an improvement over human involvement.

Americans’ views on these topics are infused with skepticism and uncertainty, but there are notes of optimism as well. People are more likely to oppose than favor AI’s involvement in reviewing job applications – and for final hiring decisions, adults decisively want human judgment to prevail. A majority say they, themselves, would not want to apply to a job where AI helps make hiring decisions. Still, when it comes to AI’s potential impact, people hold some views that are more optimistic. For instance, they lean toward thinking AI systems would be better than humans at treating all applicants the same and that AI would improve problems of racial bias and unfair treatment in hiring if it were used more.

The public remains relatively unaware of AI’s use in hiring. The majority of Americans (61%) have heard nothing at all about AI being used by employers in the hiring process. Still, 39% of Americans say they have heard at least a little about this, including 7% who have heard a lot.

Awareness of AI’s use in the hiring process varies across different groups. Those with a bachelor’s degree or more, for example, are more likely to have heard about this compared with those with some college experience or a high school diploma or less. Asian adults are most likely among racial and ethnic groups to have heard at least a little, followed by Hispanic or Black adults and a smaller share of White adults. And half of those who have applied for a job in the past 12 months have some awareness of AI’s role. (See Appendix B for full demographic details.)

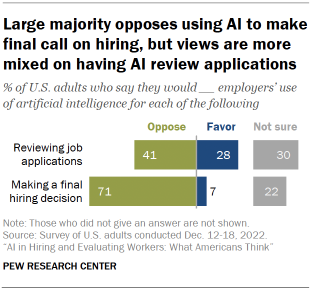

Americans are more opposed than not to AI’s involvement in the hiring process, especially in making final decisions

AI can play a range of roles in hiring – from scanning and evaluating resumes to scoring candidates or conducting interviews. While some argue humans will always be needed in the process, companies’ moves to embrace AI’s role have inspired discussion and debate about how far its influence in hiring will go.

This Pew Research Center survey takes Americans’ temperature on AI’s use at two places in the hiring process – reviewing applications (a place where experts say AI’s use is growing) and making a final decision about extending a job offer to an applicant.

While views vary somewhat based on the stage in question, Americans lean negative when asked about either. A majority of Americans (71%) oppose AI making a final hiring decision, while just 7% favor it and 22% are not sure. By comparison, views of using AI to review job applications are more mixed: A plurality (41%) opposes employers doing so and 30% are not sure what they think about this issue. But another 28% are in favor of this.

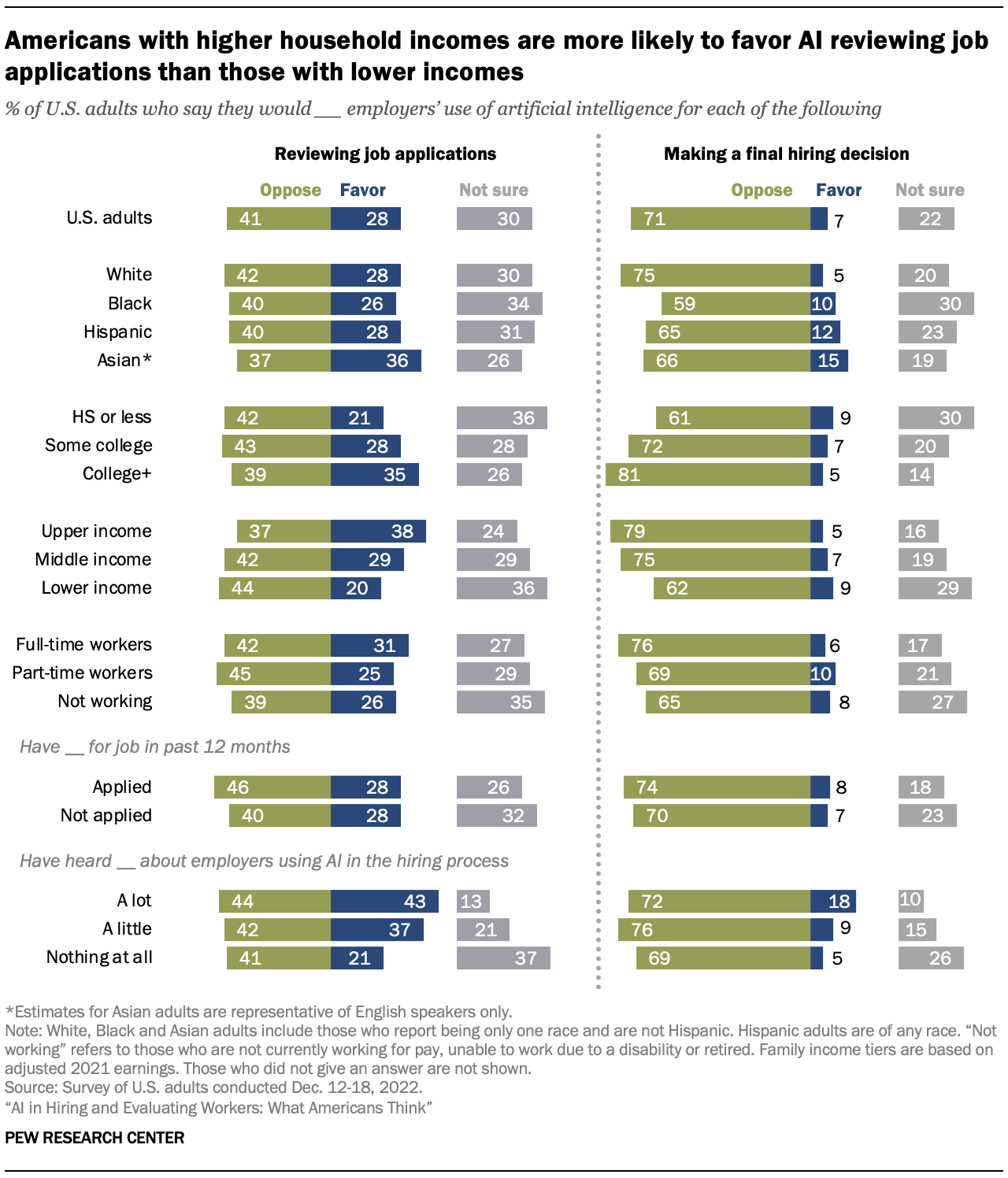

The more familiar people are with this technology, the more supportive they are of its use. For example, 43% of those who’ve heard a lot about using AI in the hiring process support its use in reviewing applications, compared with 37% who’ve heard a little and 21% who’ve heard nothing at all. Still, even those with a higher level of awareness are about evenly split between favoring and opposing this.

Americans with relatively high incomes (38%) are also more likely than those with mid-range (29%) or lower (20%) incomes to favor AI being used to review applications.

There are also differences by race and ethnicity. Asian adults are more likely than Hispanic, Black and White adults to favor AI reviewing job applications. When it comes to using AI in making the final decision, Asian, Hispanic and Black adults are more likely than their White counterparts to express favor – though relatively small shares say so in each group.

Those who are currently working are more likely to oppose a final decision being made with AI than those who are not (75% vs. 65%). However, there is variation among workers by whether they are full time or part time: 76% of full-time workers oppose this, while part-time workers (69%) hold similar views to those who are not working (65%). And those not working are more likely than people working full or part time to say they are not sure of their views about AI’s use in both stages of the hiring process.

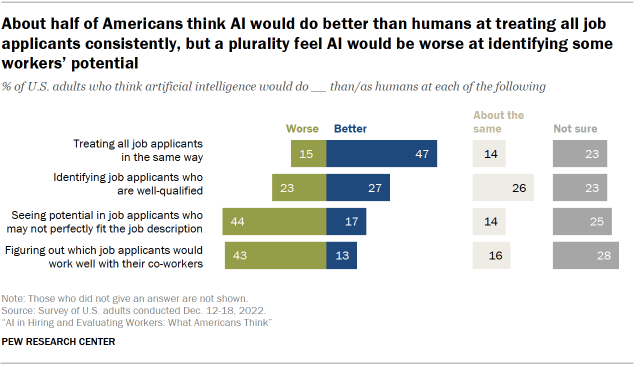

About half of Americans say AI would do a better job than humans at treating all job applicants in the same way

One of the major issues surrounding AI systems of all kinds is whether they can improve on human performance. Similar questions arise in the hiring process: Can AI programs eliminate potential flaws in human judgments? Or, will AI systems miss candidates who might be a good fit in ways not immediately apparent from their application?

Asked how AI would measure up to humans in several respects, some see places where AI might improve on humans’ abilities – for example, in treating applicants consistently. At the same time, there is considerable skepticism when it comes to looking beyond what’s on paper to see potential or assess how people will interact; on balance, people envision AI doing worse than humans at these tasks.

Out of the four topics explored in this comparison, U.S. adults are most likely to say that AI can improve over humans when it comes to holding people to a common standard. Some 47% say AI would do a better job than humans at treating all applicants in the same way – about three times the share of those who say it would do worse (15%). Some 14% say it would do about the same job.

There is no consensus when it comes to how people think AI would perform relative to humans in identifying job applicants that are well-qualified: 27% say AI would do a better job and 23% say a worse job, while 26% say about the same.

On the other hand, people are more skeptical that AI would be an improvement over humans when it comes to thinking outside the box: 44% say AI would be do a worse job at seeing potential in job applicants who may not perfectly fit the description. This is far greater than the shares who say it would do a better job (17%) or about the same job (14%).

And even as some AI tools aspire to assess employees’ “soft skills,” people are relatively skeptical about how they measure up to humans on these nuanced matters. Some 43% say AI’s judgments about who might work well with coworkers would be worse than the judgments humans would make – 30 percentage points higher than the share who think it would be an improvement over the human touch.

Still, segments of the public are uncertain about these issues. On each of the four considerations explored, about a quarter are not sure whether humans or AI would do a better job.

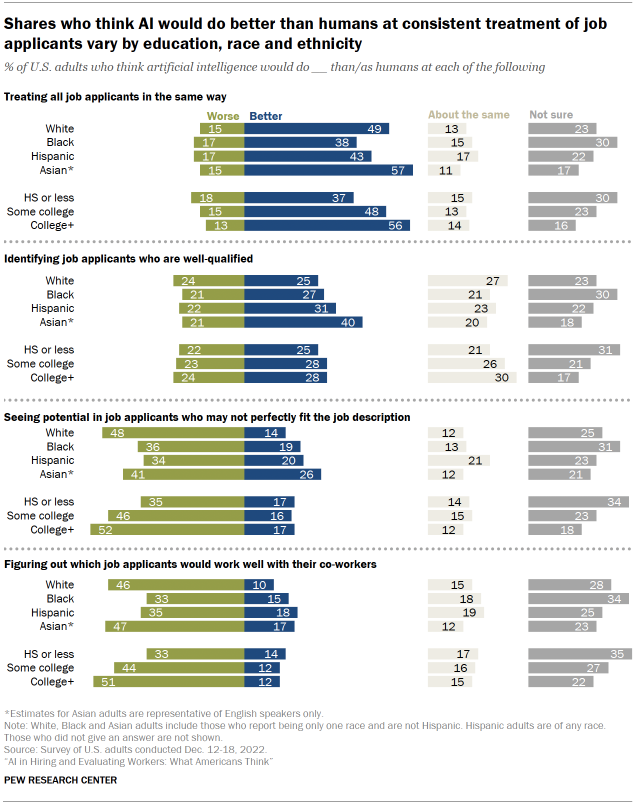

There is variation in these views across groups – with some of the largest differences by formal education, race and ethnicity.

Americans with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more likely than those with some college experience or a high school diploma or less to say AI would be an improvement over humans in treating all applicants in the same way. But pessimism rises with formal education when it comes to the job AI would do figuring out who would work well together or gauging job seekers’ hidden potential – those with a bachelor’s degree or more are about 20 points more likely than those with a high school diploma or less to say AI would do worse than humans at each.

Racial and ethnic differences in these views are also apparent. When it comes to seeing potential in job applicants and assessing their possible fit with co-workers, Black, Hispanic and Asian adults are all more likely than White adults to say AI would be an improvement over human judgment. On the other hand, Black and Hispanic adults are less likely than White or Asian adults to think AI would be an improvement over humans in treating applicants in the same way.

Further, while pluralities of Americans regardless of employment status say AI would improve on the job humans do at treating applicants consistently, those who are working full time (53%) are somewhat more likely to say this than those working part time (45%) or not working (41%). Yet full-time workers are more skeptical on other matters: For example, those working full time (49%) are more likely than those working part time (43%) or not working (35%) to say AI would be worse at figuring out who would work well with co-workers. Workers generally are also more likely to say AI would be worse at seeing potential compared with those not working (49% vs. 37%).

There are also differences by age, with adults under 50 more likely than older adults to see AI as an improvement over humans in consistent treatment of job applicants (50% vs. 43%); but also more likely to say AI would be worse at seeing the potential of job seekers (48% vs. 39%) or figuring out whether they would fit with co-workers (46% vs. 39%).

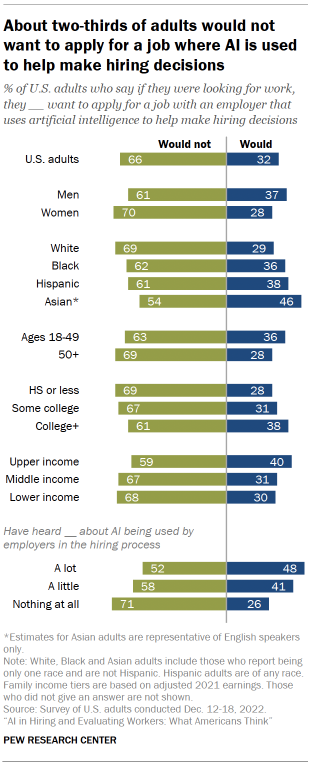

Majority of Americans would not want to apply for a job with an employer that uses AI to help make hiring decisions

Experts, regulators and human resource professionals alike are in agreement that AI is changing the way some companies hire. But how interested are Americans in actually being evaluated – in whole or in part – by a computer?

The survey reveals that Americans largely are not convinced an AI-driven hiring process is for them. About two-thirds (66%) say they would not want to apply for a job with an employer that uses AI to help make hiring decisions, while 32% would want to do so.

These preferences vary by how much people have heard about the topic. Some 71% of those who have heard nothing at all say they would not want to apply to a job where AI was involved in making the decision. This compares with 58% of those who have heard only a little and 52% of those who have heard a lot.

About seven-in-ten White adults say they would not want to apply in this case, greater than the shares of other racial and ethnic groups who say the same. Black adults are next with about six-in-ten (62%) saying they would not want to apply, greater than the share of Asian adults (54%) who say so. (The share of Hispanic adults who are opposed to applying – 61% – is statistically similar to the shares of Black or Asian adults.)

While majorities of Americans regardless of age would not want to apply for a job where AI helped with hiring, Americans 50 and older are more skeptical than those under 50 (69% vs. 63%). This age pattern is apparent when just looking among Black adults – 67% of Black adults ages 50 and up would not want to apply, versus 58% of Black adults under 50 – but not among White or Hispanic adults.

Looking at age and gender together, women 50 and older (73%) stand out from other groups in their opposition, followed by similar shares of younger women (66%) and men 50 and older (64%). A smaller share of men under 50 (58%) say they wouldn’t want to apply.

Finally, greater shares of those with lower or middle incomes would not want to apply for a job like this when compared with Americans in the upper income tier.

In broad terms, these findings are in line with earlier Center research on related topics. In a 2017 Center survey, the vast majority of Americans also said they would not want to apply for jobs that use a computer program to make hiring decisions.3

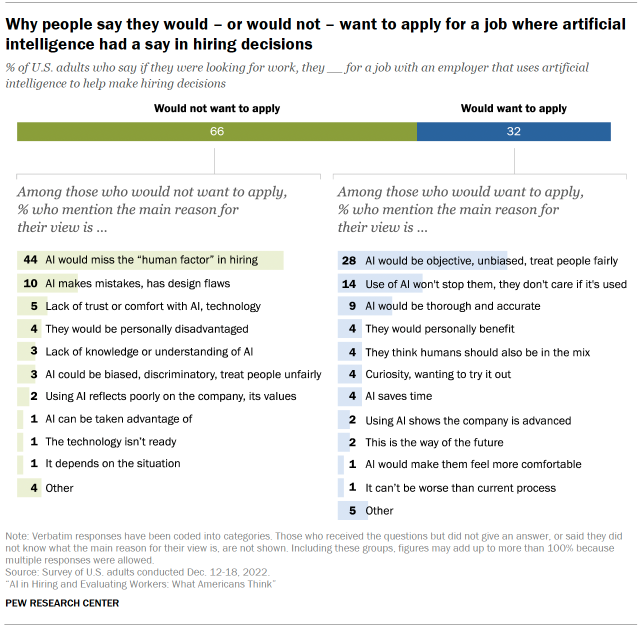

Lack of ‘human factor’ is most common reason for not wanting to apply for job that uses AI in the hiring process

When Americans are asked to give the main reason they would or would not want to apply for a job where AI is used in hiring, their own words reveal a range of potential pros and cons about the way AI would function in this process.

Among the 66% of adults who would not want to apply, a plurality (44%) mention ways AI-aided systems might ignore the “human side” of evaluating job applicants – or that they would just prefer the human touch.

Some express concern about AI’s inability to make human-like judgments or to see “intangibles” that they consider important to hiring:4

“AI can’t factor in the unquantifiable intangibles that make someone a good co-worker … or a bad co-worker. Personality traits like patience, compassion and kindness would be overlooked or undervalued.” – Man, 60s

Without humans in the hiring mix, people fear the process would become impersonal and that the lack of person-to-person interaction would be detrimental to both the employer and the prospective employee. Some discussed these concerns generally, while others noted that certain fields require qualities AI cannot see:

“That takes all the personalization out of it. I wouldn’t want to make a decision whether or not to join a company without being personally selected and without meeting my potential employer directly, and without them meeting me to see if I would be a good fit for their employees.” – Woman, 30s

“I work as a bartender. My job requires me to be social, current on social and timely topics. I also need to multitask at times, and get along as a team player. I’m not sure AI will see those attributes.” – Woman, 50s

Another 10% of people who say they would not want to apply describe concerns that the design of AI could be flawed – for some, it is too focused on keywords or absolutes, screening people out unnecessarily:

“[To AI] … I’m not a person, just a series of keywords and if I don’t fit the exact hiring model I’m immediately discarded. Hiring manager doesn’t care, they don’t actually read anything.” – Man, 40s

Others in this group discuss more fundamental problems with AI’s design or the data it uses.

“It’s a ‘garbage in, garbage out’ problem. AI in itself could be useful, but in general the parameters that it’s given are poor. There has always been a gap between the Human Resources personnel and the supervisor or team who know the actual needs, and that is exaggerated with AI. Who do you think programs the AI?” – Woman, 50s

And another 3% specifically mention design flaws in AI systems that could lead to bias, unfair treatment or discrimination:

“AIs are typically trained on real-world data which can be (and often is) inherently and systemically biased to favor privileged groups. Use of AI for decision-making perpetuates the biases we have in human decision-making. Hiring is an area where biased decision-making is especially dangerous for our society.” – Man, 20s

Small shares of those who would not want to apply also express a more general wariness, saying they do not trust AI or feel comfortable with technology (5%); worry they would not fare well if AI were used (4%); or feel too “in the dark” about what AI is or what it can do (3%).

Turning to the 32% of Americans who say they would want to apply for a job like this, the most common reason relates to the prospect that AI could be objective, fair, have little to no bias or treat everyone equally. Some 28% of those open to applying mention one of these factors as the primary reason:

“If the AI were properly informed, it could remove/minimize any personal bias of the human who would otherwise be making hiring decisions.” – Woman, 70s

Another 14% of the individuals open to applying for a job with AI in the hiring decision process say that fact is not going to stop them from applying or does not matter to them.

“If I was looking to change jobs, I would apply to potential employers because of the quality of their culture and how the job that is being offered matched my goals and skill sets, and much less how AI is used in the selection process.” – Man, 60s

“Because I need a job if I am applying. It’s not like I have much of a choice.” – Woman, 20s

About one-in-ten (9%) of those open to applying argue that AI would be thorough and accurate – possibly more so than humans:

“I think the AI would be able to evaluate all my skills and experience in their entirety where a human may focus just on what the job requires. The AI would see beyond the present and see my potential over time.” – Man, 50s

Still, 4% of this group say humans should still be involved at some level. And small shares also note positives like AI giving them personally a leg up, being curious to try it or making hiring efficient (4% each).

“I have been part of a company’s hiring process in the past, and having to sort through thousands of applications was time consuming and tedious. Using AI to streamline that process sounds like a good advancement.” – Woman, 20s

A majority say racial and ethnic bias in hiring is a problem, and about half of them say increased use of AI would help ease those issues

The rise of AI in hiring has spurred societal debates about what it means for diversity, discrimination and bias in the hiring process – especially when it comes to applicants’ treatment based on race or ethnicity. AI’s advocates say it could eliminate unconscious bias and improve diversity in the workplace. But others sound alarms, raising concerns about AI’s potential to entrench existing biases and make discriminatory decisions.

These issues are being actively debated by lawmakers and regulatory bodies alike, and companies are facing lawsuits over alleged algorithmic discrimination in hiring. They are also situated amid broader concerns about diversity and discrimination in the workplace based on race and ethnicity.

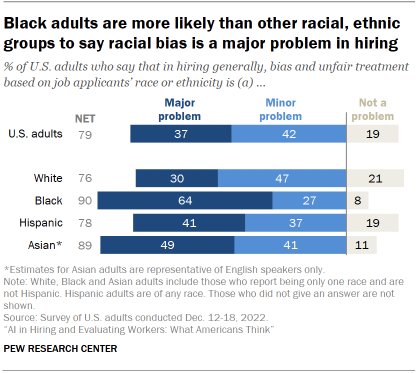

In this survey, a majority of Americans (79%) say that in hiring generally, bias and unfair treatment based on job applicants’ race or ethnicity is a major (37%) or minor (42%) problem. Some 19% believe this type of discrimination in hiring is not an issue.

Black adults stand out from other racial and ethnic groups in thinking this is a major issue. About two-thirds of Black adults (64%) say bias and unfair treatment based on race or ethnicity is a major problem, as do smaller shares of Asian (49%) and Hispanic (41%) adults. White adults are least likely among racial and ethnic groups to say this (30% think it is a major problem). Among White adults, this view differs by age, with White adults under 50 more likely to think it is a major problem than their counterparts who are 50 and older (34% vs. 26%). Among Black or Hispanic adults, there are no age differences in viewing this as a major problem.

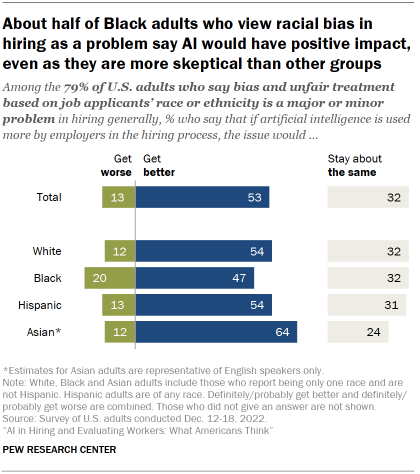

Americans who think bias and unfair treatment is a problem in hiring are, on balance, optimistic about AI’s potential to improve things if it plays a greater role in the process. Far more among this group say this problem would definitely or probably get better with increased use of AI in hiring (53%) than say it would definitely or probably get worse (13%). About a third (32%) say things would stay about the same.

Across racial and ethnic groups, about half or more of those who think bias and unfair treatment based on race or ethnicity is a problem say that this will get better with increased use of AI. Asian adults who believe this is a problem are more likely than other groups to say it would improve, followed by equal shares of their White or Hispanic peers who say so.

One-in-five Black adults who say this is a problem think it will get worse with increased use of AI, compared with about one-in-ten of those who are Asian, Hispanic or White. Still, 47% of Black adults who say this is a problem are optimistic about the impact of AI’s increasing use.

Looking at these issues among the general population, 42% of all Americans say racial and ethnic bias in hiring is a problem and that this would get better with increased use of AI; 10% say it is a problem and this would get worse; and 25% say it is a problem but would stay the same. Another 19% say it is not a problem to begin with.