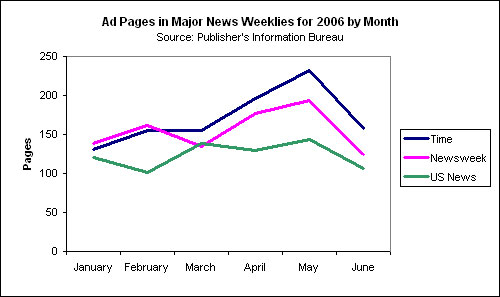

The news magazine business, like many old media platforms, is facing its share of concerns. Given the growing emphasis on real time news and instant commentary, these publications – with their weekly schedules and more reflective, analytical approach – are increasingly seen as anachronisms in this new media landscape. And long-time industry leaders like Time, Newsweek and US News & World Report are seeing their circulation and ad pages shrink regularly.

The three big news titles had a particularly rough 2005. Ad pages dropped at all of them with Time and Newsweek witnessing double-digit declines. Last year, circulation for Time and Newsweek was at its lowest point at any time in almost 20 years with US News registering its second lowest circulation count in nearly two decades. Staffs were slashed as well. Last year, Time Inc. laid off 105 people from throughout the organization including Time bureau chiefs in Moscow, Beijing, Seoul and Tokyo. US News endured cuts that reached into the upper levels of the masthead.

But at the same time, titles like The Week and the London-based Economist are experiencing rapid growth in US readership and better advertising performance. This suggests that different editorial models can succeed in a difficult environment and that readers may be looking for creative variations on the traditional American news magazine approach.

In this, the fourth of our roundtables on the future of the news media, magazine industry experts see change as not only inevitable, but essential if the publications are to continue to survive. But they disagree about just what those changes should entail.

The panelists for this roundtable are:

- William Falk, Editor, The Week

- Samir Husni, Chairperson, University of Mississippi Journalism Department and author of Samir Husni’s Guide to New Magazines

- Daniel Okrent, former Editor, Time Inc. new media

- Victor Navasky, Chairman, Columbia Journalism Review, former Editor, The Nation

1. The death of the news weekly has been predicted for years, but somehow they’ve managed to survive. Does today’s news climate and the recent cutbacks at Time and U.S. News pose more of a real threat? What sort of future do you see for the weekly news magazine?

Daniel Okrent: The news magazines will have to change to survive, and I expect they’ll do so. The compression of the news cycle has placed breaking news in the hands of digital providers, compelling deeper analytical efforts by daily newspapers, and thus depriving the news weeklies of their traditional specialty. I wouldn’t be surprised to see them revert to what Henry Luce and Briton Hadden first imagined eight decades ago: something to break through the clutter.

Victor Navasky: I see the news weeklies becoming more analytical, interpretive, and perhaps even opinionated.

Samir Husni: I do not believe the recent cutbacks at the news titles are related to the news climate as much as to the content of those magazines. When you reach a stage in the midst of a country which is facing war, terrorism and political upheaval, and you have at least four cover stories in the last six months on teenagers and teenage boys and being 13, etc., you wonder “how were they able to maintain the level of circulation that they have?”

I have heard some folks referring to the new definition of news as “whatever affects your lifestyle,” but I don’t believe that, in this day and age where everything is presented in nuggets, that the role of the news weeklies should not revert to – as the Wall Street Journal Europe calls it – the breaking views. Unless those weeklies go back to covering the news in its pure, journalistic-defined form, I don’t think the future will be great for them.

William Falk: Obviously, I’m biased, but I think the news magazine will remain an important facet of many people’s media consumption. News magazines provide big-picture perspective that daily products cannot; they help readers make sense of what they’ve already read about or experienced. There is also a sense of craft and polish about weekly magazines that provides an enjoyable reading experience.

2. Along the same lines, news magazines have done surprisingly little to create an existence on the web. What has been holding them back? Can their content, including pictures, transfer to the web?

Falk: That is changing, as all the news magazines (including The Week) beef up and diversify their web sites. For the next five or ten years, I think the sites will be function primarily to supplement and add web-friendly content such as blogs to the print products. After that, my crystal ball is very cloudy.

Okrent: The web asks for speed, and news weeklies are not built for speed. But I do see them investing more heavily in web efforts right now that take advantage of their distinctive voices.

Husni: I don’t think the premise is true. Time and Newsweek are very active on the web, very active in delivering their information to their subscribers a day before the print edition is out and very active in occasionally breaking news stories on their website before the printed edition. If they are guilty of one thing, they are guilty of not sending the readers back from the web to the printed edition. We have managed to create a one-way street from the printed edition to the web, with no way back.

Now, the question is, “can their content, including the pictures, transfer to the web?” Definitely it can, but again, for what reason?

Navasky: What has been holding the news weeklies back has been the assumption that their content should be “transferred” to the web. The secret is to create content appropriate to the new medium – interactive, Q&A’s, chat-rooms, maybe each magazine will create its own spin-off web-versions of “Meet the Press”.

3. Over the last two years niche news magazines like the New Yorker and the Economist and most recently The Week have seen strong growth in both circulation and ad revenue. How far can this growth go considering they are niche genres? What does this suggest about the magazine reader of the future?

Falk: Again, I’m biased, but I strongly believe that each of the three magazines can continue to grow.

At The Week, we have found that people are extremely enthusiastic about a magazine that filters and make sense of so much commentary and news. One measure of that is how our subscribers proselytize their friends. In the past year alone, readers have bought more than 100,000 gift subscriptions to friends and family members.

The New Yorker, the Economist, and The Week are very different publications, obviously, but what we have in common is that we help people make sense of news they’ve already heard. In an age in which we are all literally inundated with media, people are often overwhelmed and unsure what to read and what to think. That creates a demand for an intelligent, trustworthy guide like The Week.

Husni: This is the beauty of the magazine industry – there is something for everyone and, while The New Yorker continues to dwell on in-depth and the coverage of one big story at a time, The Week, on the other hand, provides you cliff notes of all that’s taking place, not to mention The Economist weighs in with their views and analysis for those of us who actually have the luxury of trying to understand the world beyond the outer crust of our planet.

What does this suggest about the magazine reader of the future? Simply stated, the magazine reader of the future is going to be the same as the magazine reader of today, as the magazine reader of yesterday, and as the magazine reader of tomorrow. The magazine reader will continue to search for the publication that will best meet their needs, wants and desires.

Okrent: It in fact suggests that the distinctive voices I cite in the answer to concerning creating an existence on the web will be the vehicles to lead news weeklies back into their previous prominence.

Navasky: Ad growth seems to me to say more about the consumer of the future than the reader of the future. And the term niche seems too vague an umbrella under which to lump the three you mention. Each of the magazines you cite is a case unto itself: I think The Atlantic’s move to Washington will contribute to a period of confusion rather than growth; The New Yorker is a quality-lit and entertainment magazine; The Week is the latest adaptation of the Reader’s Digest formula. In theory these latter two mags could attract an abundance of new advertising.

4. Considering the flood of information available to consumers now and the magazine’s primary role of putting the news into perspective, how important do you think a large, geographically spread staff is?

Falk: Frankly, it depends. There is still an important role for what Time and Newsweek do with their domestic and international bureaus, and it’s hard to imagine those fine magazines without that reportage. But it’s not necessary for all magazines to replicate this approach. At The Week, our role is different: For foreign perspective, we don’t send reporters abroad, but tell readers directly what newspapers are saying in Europe, the Mideast, Asia, and other parts of the world. That is not only far less costly, it provides a unique value: It’s one thing to have an American reporter tell you what Arabs think of the Guantanamo prison. It’s another to hear it directly from Arabs.

Okrent: Less so – partly for the reasons suggested in the question, but also because of the efflorescence of news sources scattered around the world. The modern news magazine will be able to – will be compelled to – make alliances with non-competitive providers for news they can’t gather on their own.

Navasky: More important than ever. Yesterday I was talking with an American businessman who specializes in Latin American investments. He tells me that any American businessman who spends any time in, say, Argentina will quickly see that America doesn’t mater any more – they look to China rather than America as a major force. I don’t know whether that’s true or not, but do know that without our newspapers and magazines having their own people on the ground, we are missing these perspectives.

Husni: On one hand, we talk about how the world is flat. And, on the other hand, we want to confine everything to Washington D.C. and New York City. I don’t think location (of staff) matters. To paraphrase President Clinton, it’s the content, stupid.

5. Why do you think it has been that the biggest magazine owners have shied away from news titles? Conde Nast, for example, has added business titles even as business titles are slumping. How big a factor is the traditional cost associated with operating a news magazine?

Falk: Cost is a huge factor for traditional news organizations, since their staffs are so large. Another problem is that news magazines do not do well on newsstands, compared to “sexier,’’ impulse buys with celebrities on the cover.

Navasky: Lack of imagination is why people are shying away. I think the next generation of news weeklies may be multi-media as mentioned in the question about moving to the web and they will start from the points where politics and culture intersect.

Okrent: The traditional cost is an enormous factor, even as costs have been stripped away. The apparent difficulties in the news category certainly aren’t going to lure new players into the space.

Husni: As far as I remember, the last major mass-news weekly published in the United States was published in the 1930s. So the question is, why did we wait nearly 80 years to ask this question? I think the feeling is that three is plenty to cover this medium. Plus, let’s not forget that the newspapers are, themselves, becoming daily magazines.

6. One broad trend we sense in the media culture is the paradox of more outlets covering fewer stories. As the audiences for particular news outlets shrink, newsroom resources are then reduced, but these outlets still feel compelled to cover the big events of the day. The result is more outlets covering those same “big” events and fewer are covering much beyond that as much as they once did. How do you view this trend?

Navasky: You ask how do I view this trend? With alarm. The reason is that although you refer to “more” outlets, they are owned by fewer and fewer, larger and larger corporations, which means a narrower range of perspectives. A hopeful countertrend: Small independents, such as the hundreds of periodicals represented by the San Francisco-based Independent Press Association.

Okrent: I’m not sure I agree with the premise. While this may the case at the apex of the media pyramid – i.e., the networks, the major news magazines, the national papers – the true expansion of media outlets is happening, and will be happening, at the base. I think we’re going to see this happening at the local level especially, and where there’s good local journalism, there will be stories that will be picked up and disseminated nationally.

Husni: Well, I hate to disagree from the outset with this premise, but it’s a little off on two fronts. One, that media outlets are covering fewer stories and, two, that everybody is covering the same big event of the day. If we really look at the daily newspapers and the more-than-daily websites, we see that there is a stream of information continuously converging toward the reader, packaged in different ways. It may give the appearance that there is less information or that it’s shorter, but, in reality, it’s the same old wolf, just now in sheep’s clothing.

I wish that the media outlets would cover more stories in depth and less with the barrage of information that we all see on a regular basis. I think that it’s only a figment of the imagination of the people in the media to believe that the same reader is going to jump from their newspaper to the website, to the television channel, to the radio to read scan, listen and view the same story. Wishful thinking at best.

As for the audience, I don’t believe it’s shrinking. The major news weeklies have maintained their circulation bases for years now, and the marketplace has added many more choices and options. Now, if we are going to define what we mean by news, that’s, of course, a completely different story. Because, what’s news for me and you is not news for Joe Smith and Sally Jane.

Falk: I am distressed by it. I think of this as the “O.J.’’ syndrome, perhaps because I was a reporter at Newsday at the time and saw first hand how much one story could consume a major news organization. It was during that case that this trend really became pronounced, and ever since then, TV, newspapers, and magazines seem to focus on one Big Story for months at a time.

I understand why editors who are worried about competition, circulation and ratings would succumb to the temptation to devote their resources to covering the same story or stories everyone else is covering. Nonetheless, it’s undermining both the validity and the appeal of traditional journalism. Obsessing over one story, even when there is hardly anything new to say, makes readers cynical about our claims to high motives. It also reduces the need for people to buy our publications, since they so rarely see anything truly original or surprising.

Traditional newspapers and magazines will survive, I think, only if they break stories, do investigative work, and prove to the public day in and day out that we’re their advocates.

7. How much confidence do you have that traditional mainstream media organizations will survive and thrive in the transition to the Internet?

Husni: 110 percent. To paraphrase Mark Twain, the news of the death of the traditional mainstream media has been greatly exaggerated. I was told “print is dead” as a student in 1980 when video text was introduced (I guess you’re probably wondering, what’s video text?). I was told “print is dead” when videotapes and CD-Roms were introduced in the early 90s. I was told “print is dead” in the late 90s when the dot-com became the in thing. And, now, I get yet another question about whether or not mainstream media will survive in the internet age. Being a gambler, and looking at the odds, I’ll still place my bets on the mainstream media’s survival. And not merely surviving, but surviving and thriving at the same time. They’re not going to be transitioning to the Internet. They’re going to be using the internet to complement and enhance the printed product.

Falk: There will undoubtedly be a shakeout. But I cannot imagine major newspapers such as The New York Times, The Washington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and the Chicago Tribune failing to make the transition. Their reporting, news analysis, and commentary still forms the backbone of the entire media, both electronic and web; without the work their very large and talented staffs do, non-traditional media would have little to say or react to. Though imperfect, these and other major newspapers provide truly astonishing amounts of information and ideas every day. They have a product that the world will continue to need, regardless of how it is delivered.

Navasky: I suspect that some traditional mainstream media organizations will survive and thrive and others will go under; and others will survive in new, mixed- and multi- media forms. I believe that instead of replacing old media, if properly managed, the internet will extend and augment the old media.

Okrent: They won’t survive in the present form. Digital distribution (not Internet alone) will force existing media organizations to carry their brands into the digital domain, perhaps exclusively.

8. Do you think the economic model of the Internet has to shift from an advertising based model to something else for traditional journalism to survive at a level that we have become accustomed to? If so, do you have any thoughts on what that new model might be?

Falk: I do suspect that as traditional media rely more heavily on web readership, they will have to find a way to charge for access to their sites. It’s difficult to do so now, because so much is available for free; but as the economics drives publishers to start charging small fees, it will become more viable.

Okrent: I anticipate a model that could not have existed in the pre-digital age: readers will be able to choose free content subsidized by, and cluttered by, advertising – or, if they prefer, they will be able to pay for it and not have to endure the advertising. Additionally, once current providers recognize the vast savings in physical costs and distribution costs that digital distribution will afford them, they’ll reconstruct a much more favorable business model from the ground up.

Husni: Do you remember black and white television with a knob, where you had to move from your couch and go to the TV to change it to one of the three channels? Three televisions networks, one TV set, at a cost of less than $200, and you had television for life. Who would have ever thought that consumers would be paying an average of $60 a month to watch the same junk that they used to watch for free? I think that will be the model for the future, where if you really want to get what you are looking for, and be able to connect to it, you will have to pay. For now, all that we pay for is the access. Pretty soon we’ll have to pay for the content.

Navasky: It is important to distinguish among big and little media. Certainly the advertising-based economic model is one way to go. But in the case of The Nation the main initial consequence of the Internet has been to attract new, paying subscribers to the hard-copy magazine who come to us via our free website. As far as big media goes, although it’s a way off, the internet could revolutionize direct mail.

The threat to newspapers now appears from nearly every indicator. From 1950 through 1999, for instance, newspaper revenue grew seven percent a year. From 2000 through 2006, by contrast, it has grown by just 0.5%. Then in the first quarter of 2006, growth was even less: 0.35%.