In the final two crucial weeks of the general election campaign, as Scott Brown came from behind to defeat Martha Coakley, the tone of coverage of the two candidates became a study in contrasts—and a portrait of how the press can turn on candidates that it once portrayed quite differently.

To assess the tone of coverage in this report, each story in which a candidate was a significant figure was examined for whether those assertions in total were predominately negative, positive or mixed. For a story to be categorized as clearly positive, positive assertions about the candidate would have to outnumber negative ones by a factor of 1.5 to 1. For a story to be negative, the reverse would have to be the case. Any story that did not meet that threshold, or where the assertions were largely balanced, was categorized as neutral.

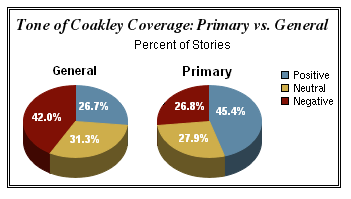

For Coakley, who had received largely positive coverage during her Democratic primary win, the tone of her coverage went decidedly south. Fully 42% of the stories and opinion pieces about her from January 6-19 were negative, compared with only 27% positive and 31% that were neutral.

Conversely, in that same period Scott Brown generated far more upbeat coverage as 42% of the stories about him were positive, compared with only 16% that were negative. Another 42% were neutral. He was clearly winning the media narrative and by a wide margin.

Those same differences in tone are closely reflected in the coverage of the dominant subject during the general election campaign—political topics. Indeed, 29% of political stories about Coakley were positive, 43% were negative and 29% were neutral, while 46% of Brown’s political stories were positive, compared with 15% negative and 39% neutral.

A PEJ study of the final weeks of the 2008 presidential campaign when Barack Obama generated significantly more positive coverage than John McCain, indicated that the candidate who is doing better strategically—the one perceived to be winning or gaining—is likely to receive the more flattering coverage. That seems to be what happened in the final days of the Massachusetts campaign as well.

The tone of general election coverage in the New York Times and Associated Press supports that idea. While coverage of Coakley in the last two weeks of the general campaign was mixed in both the Times and AP, not one of the nearly 40 stories about Brown by those two outlets in that period was coded as negative in this study.

In those final weeks, Coakley, who had cruised to the Democratic nomination with a cautious and careful campaign, found the narrative turning against her as it became apparent she was squandering what had once been a 30-point lead in the polls. Some of that coverage was driven by unforced errors on her part.

Between January 6-12, a Coakley ad misspelled “Massachusetts” and another showed the destroyed World Trade Center towers as a symbol of Wall Street greed. While trying to make the point that the war on terror had moved beyond its original borders, she claimed there were no more terrorists in Afghanistan, despite a recent spike in violence. After a fundraiser in Washington, D.C., one of her aides appeared to push a reporter for the conservative Weekly Standard to the ground as he attempted to question her.

Perhaps more unforgivable, in the heart of Red Sox nation, was that Coakley called ex-Sox pitching star Curt Schilling “another Yankee fan” during a radio interview. She claimed to have been making a joke, but the media and Schilling pounced, painting her as out of touch with one of the most common threads in the Bay State: its beloved baseball team.

The fact that Coakley appeared at fewer public events than Brown and had taken a six-day break in December also became part of the storyline. The Herald called the time off an “ignorant respite” that allowed Brown to “…define himself and to define her.” Coakley also snapped when a reporter asked about her campaign style, mocking the idea of a candidate shaking hands in the cold outside Fenway Park. This was a jab at Brown, who pressed the flesh outside a Boston Bruins outdoor hockey game at Fenway Park on News Year’s Day. The episode prompted a Globe op-ed to call her “sneering and elitist.”

When Coakley claimed to have campaigned thoroughly across the state, Globe columnist Brian McGrory wondered if “it was under the cover of darkness, under an assumed name.”

The Herald was even harsher. Columnist Margery Eagan called Coakley “…a lackluster, uptight bore” running a “let-them-eat-cake” campaign. Columnist Howie Carr repeatedly called the Democrat a “moonbat” and opened one of his pieces pleading with anyone to “buy Martha Coakley a clue.”

During a series of debates, Brown seemed to best Coakley at several key moments. In a January 8 face-off, Brown parried Coakley’s attempts to tie him to George W. Bush and Dick Cheney by saying “… you’re not running against them. I’m Scott Brown from Wrentham, and you’re running against me.” In the final debate on January 11, when Brown was asked if he would vote to block health care as the successor to the senator who it made it his signature issue, Brown responded, “It’s not the Kennedys’ seat. It’s not the Democrats’ seat. It’s the people’s seat.”

That was in keeping with Brown’s populist persona on the campaign trail, something he continually stressed by noting that he was from Wrentham (a small town southwest of Boston) and drove a truck.

And by the second week in January, polls either had Brown in a virtual tie with Coakley or even inching ahead.

Tone for Coakley and Brown in the Primary Campaign

Technically, Brown’s positive coverage in the final weeks of the general election campaign was similar to the tone of his primary coverage. From September 1-December 8, a full 54% of his coverage was positive, compared with only 7% negative and 39% mixed. But he generated so little attention in that period that those numbers don’t tell us much.

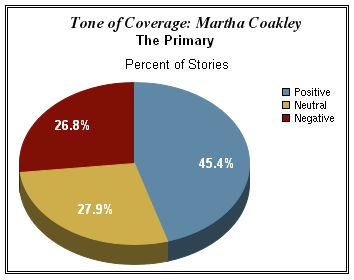

But an examination of Coakley’s primary coverage illustrates the dramatic downward spiral. From September 1-December 8, fully 45% of her coverage was positive in tone, compared with 27% that was negative, while 28% was mixed or neutral.

At least some of that positive coverage came from the horse-race orientation of the coverage and the sense that she was likely to win the nomination. But even then, the press generally portrayed Coakley as technocratic and competent if stiff and somewhat short on charisma, a portrait that in some ways foreshadowed her shortcomings in the general election campaign.

“A Charisma Shortage,” read a Globe headline on November 20. “Caution, ambition mix in Coakley’s methodical journey,” read another three days before that.

As Globe columnist Adrian Walker put it November 20 in response to a Coakley speech, it “was all polished and professional, if devoid of sizzle; even the applause seemed dutiful. In that sense, it reflected a campaign that has always felt a tad mechanical.”

Tone for the Other Democratic Primary Candidates

Michael Capuano

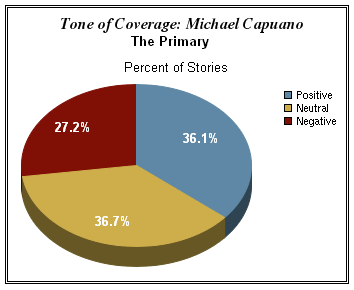

The media portrayed Congressman Michael Capuano, the scrappy ex-mayor of Somerville, as a man with a mercurial temper who prided himself on his local origins, working class roots and street smarts.

As the race went on, some press coverage described this as inauthentic in light of his Dartmouth education, his wealth, expense account trips to Europe and his establishment record. He was the biggest Kennedy loyalist in the race, portraying himself as Ted’s natural successor.

In the end his coverage was more mixed than anything else, 37% neutral or mixed vs. 36% positive and 27% negative.

“The blunt, plainspoken former mayor of Somerville, has blue-collar roots…but an Ivy League pedigree after attending Dartmouth College,” the Associated Press described him on September 16.

Even the Herald endorsement in the primary had a qualified character in tone. “The reality is that as smart—and committed—as the Democratic contenders for U.S. Senate are, no flesh-and-blood human being can duplicate the four decades of experience the late Sen. Ted Kennedy brought to the job,” the Herald wrote on December 1.

Alan Khazei

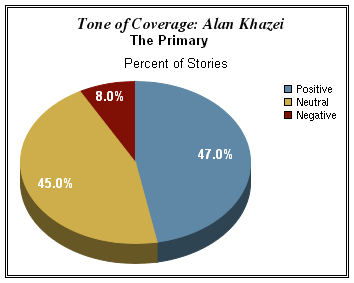

Portrayed as a quixotic above-the-fray idealist, an intellectual and humanist, Alan Khazei was, by the numbers at least, the race’s media darling.

He was also the

closest thing to an Obama Democrat, a former community organizer with a “yes we can” audacity, a grassroots organization, popularity with young people and outsider status. The Brookline native and Harvard graduate, Khazei made his name politically by creating the nonprofit program City Year, which deploys teenagers and young adults to community service work, such as mentoring school children.

It translated into clearly positive press. Overall, only 8% of the stories involving Khazei had a clearly negative tone. By contrast, 47% of his stories were clearly positive, and 45% were mixed or neutral.

Some of that coverage reflected amusement toward Khazei’s idealism. During a debate, Herald columnist Margery Eagan wrote on Oct. 27, “Khazei showed his quick Harvard brain and passionate outrage, particularly when he called on citizens ‘to rise up’ and join his crusade against casino gambling. They won’t but it was nice to hear him ask.”

But some, such as a Globe piece about Khazei’s fundraising in Hollywood, were more strictly positive. “Alan Khazei clearly has the Hollywood buzz factor,” Matt Viser’s piece read, quoting the creator of the TV shows “Lost” and “Fringe” about the “urgent alarm” to get Khazei elected.

Stephen Pagliuca

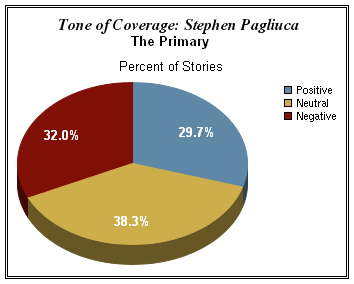

If Khazei got the best press, Harvard Business School graduate Stephen Pagliuca, the millionaire co-owner of the Boston Celtics, got the worst, though it was not lopsidedly negative.

In the end, 32% of stories involving the businessman were negative, while 30% were positive. Most, 38%, were mixed or neutral.

But reading the stories carefully, Pagliuca was at times portrayed (especially in the Herald) as a dilettante millionaire seeking the Senate seat like a new toy. The media frequently drew attention to the apparent disconnect between his liberal populist program and his many years at Bain Capital, a private equity firm in Boston, his support for his former Bain partner Mitt Romney in the race for President and his past as a “corporate raider” responsible for factory buy-outs and closures. Because he funded his campaign largely from his own personal fortune, he got the nickname “Money Pags.”

Some of the Herald news reporting on Pagliuca read like a kind of snarky code. “Multimillionaire Stephen Pagliuca—who bought the Boston Celtics and toyed with the idea of taking over the Boston Globe—yesterday addressed concerns he’s a dilettante trying to buy the seat vacated by Sen. Edward Kennedy,” Edward Mason reported in the Herald on September 18.

Some Globe coverage was not that different. “Latest megamillionaire eager to start his political career at the top,” declared a Globe article on October 3.