How Newspapers are Faring Trying to Build Digital Revenue

A new study, which combines detailed proprietary data from individual newspapers with in-depth interviews at more than a dozen major media companies, finds that the search for a new revenue model to revive the newspaper industry is making only halting progress but that some individual newspapers are faring much better than the industry overall and may provide signs of a path forward.

In general, the shift to replace losses in print ad revenue with new digital revenue is taking longer and proving more difficult than executives want and at the current rate most newspapers continue to contract with alarming speed, according to the study by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism. Cultural inertia is a major factor. Most papers are not putting significant effort into the new digital revenue categories that, while small now, are expected to provide most the growth in the future. To different degrees, executives predict newsrooms will continue to shrink, more papers will close and many surviving papers will deliver a print edition only a few days a week.

But some papers are performing quite differently than the norm, some much better and some far worse. These variances suggest that the future of newspapers, rather than being determined entirely by sweeping trends, can be significantly affected by company culture and management-even at papers of quite different sizes.

The study involved 38 newspapers from six different companies providing highly granular data about their digital revenue and sales efforts-creating a robust series of case studies. The data sought were developed in consultation with the partnering newspaper companies after site visits and interviews with multiple executives. After collecting the data, researchers conducted follow-up interviews to confirm whether the findings reflected broader company performance. Those findings, in turn, were shared with executives from seven more companies to test how widely they could be generalized. All data was provided on the basis that it would be anonymous.

This multi-faceted approach allowed researchers to draw broad conclusions and identify specific case studies, which reveal more than can be discerned from public industry data. The research approach also yielded a high level of candor in discussions with executives.

The vast majority of papers in the United States are small, something that is reflected in our sample. Of the papers that provided detailed data, 22 have circulations under 25,000, seven have circulations between 25,000 and 50,000, and nine have circulations of 50,000 or more (including three with circulations more than 100,000).

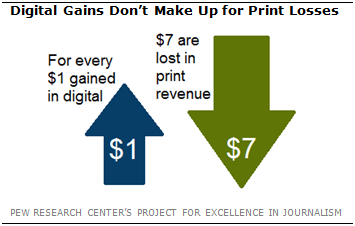

Across operations of different sizes in different types of economic settings, the newspapers studied were, on average, losing print advertising dollars at seven times the rate that they were growing digital ad revenue in the last year for which they had complete data.

Executives at the 13 companies involved in this report confirmed that closing the revenue gap remains an uphill and existential struggle. The most optimistic projections saw digital gains overcoming print losses within a few years; the most pessimistic held that it would never occur. A number of executives said they did not know when it might happen.

Of the 38 papers that provided detailed data about their operations, not all were achieving growth in digital revenue. Seven of those studied suffered declines for the last year for which they had full data. One stayed the same year to year.

Beneath these broad numbers, however, are papers that buck the trend in significant ways and offer the idea that more can be achieved. One paper studied saw digital ad revenue grow 63% and print grow 8% in the last full year for which it had data. Another paper registered a gain of 50% in digital advertising.

Some of these outliers also were having more success growing new categories of digital revenue, not just selling the traditional categories more effectively. One of the papers generating the most digital revenue, for instance, was having significant success selling targeted digital advertising customized based on customer online behavior. This is projected to be the biggest growth area in local digital advertising. Most papers studied had very little of this kind of “smart” advertising.

Another company has had dramatic success building a new multi-million dollar a year consulting business helping advertisers and other businesses learn how to market themselves in the digital landscape.

At the other end of the spectrum, some papers are falling further and further behind. One paper studied saw digital revenue fall by 37% in the last year for which there are full data. Another paper saw digital revenue fall by 25%.

The growth in digital revenue is generally slower at smaller papers than at larger ones, though so is the decline in print advertising. That suggests that while the small papers that make up the vast majority of U.S. dailies are not changing as quickly as larger ones, they may have more time to sort out their way.

Many of the executives who were interviewed are enthusiastic about the prospect for mobile revenue, but so far it amounts to very little.

At the same time, newspapers have made only marginal progress in developing new non-advertising revenue streams, such as hosting events, creating digital retail malls that provide transaction fees or, with the exception of a few papers, becoming digital marketing consultants for their advertisers.

The industry is inhibited by several obstacles that executives themselves candidly acknowledge. One involves the difficulty of changing the behavior of people trained in the ways of a mature and monopolistic industry. Still another is the unavoidable fact that the part of the newspaper industry that is growing, digital, continues to provide only a small part of the revenue, while the part that is shrinking, print, provides most of the money-a paradox that is difficult to navigate and hard to resist. One pervasive feeling is that 15 years into the digital transition, executives still feel they are in the early stages of figuring out a how to proceed.

[new]

Another senior executive, capturing a sentiment articulated by many of his peers, talked about a culture of “inertia” that made change more difficult.

Another executive told us bluntly, “There’s no doubt we’re going out of business right now.”

The problem, he explained, is the dilemma that faces many trying to innovate inside older industries. If you changed your company and did not succeed, that could hasten the end of the enterprise. “There might be a 90% chance you’ll accelerate the decline if you gamble and a 10% chance you might find the new model,” he said. “No one is willing to take that chance.”

Among the key findings in this report:

- The broad numbers about the digital revenue transition are stark. The papers providing detailed data took in roughly $11 in print revenue for every $1 they attracted online in the last full year for which they had data. Thus, even though the total digital advertising revenues from those newspapers rose on average 19% in the last full year, that did not come anywhere close to making up for the dollars lost as a result of 9% declines in print advertising. The displacement ratio in the sample was a loss of dollars by about 7-to-1.

- Only 40% of the papers that provided data say targeted advertising is a major part of their sales effort. Even though many newspapers are not focusing on it, smart or targeted digital advertising—in which ads are customized based on consumer online behavior—is expected to dominate local digital revenue by 2014.

- The majority of papers studied focus most of their digital sales efforts on the two categories of digital advertising that are the largest but are not growing-conventional display (such as banner ads) and digital classified. Those categories account on average for 76% of digital revenue at the papers studied. These are the same two categories that have provided most of their revenue in print. And 92% of the papers studied said display was a major focus of their digital sales effort.

- Daily Deals accounted for 5% of overall digital revenue in 2011 at the papers studied. One of the bigger innovations in the last year, the move toward coupons or daily deals (such as Groupon), accounted in the end for only a small amount of digital revenue in 2011. A majority of all the papers studied-30 of them-have adopted such programs and most created their own programs. But there are widely varying views in the industry on the future of this category. Some executives are convinced it represents a solid revenue source going forward. Others see the deal gold rush as a bubble that has already reached its peak.

- Of the papers sharing private data, advertising on mobile devices accounted for only 1% of the digital revenue in 2011. Executives are generally excited by the prospects of mobile, but for now it accounts for a tiny amount of revenue. Executives also believe that due to its ubiquity in the market, the phone ultimately could be more important to mobile revenue than tablets, a sign perhaps of some growing uncertainty about the ability to charge for apps, though some executives are already skeptical about how much money newspapers can make with smartphones.

- Almost half (44%) of the newspapers sharing data for this study reported that they were trying to develop some form of nontraditional revenue, such as holding events or consulting or selling new business products. In most cases, the dollars involved are minimal-less than $10,000 quarterly. Some executives also expressed concern that their companies don’t have the resources or competencies for such undertakings. Still, there were a few cases of remarkable success here.

- Among the papers that provided data, the number of print-focused sales representatives outnumbered digital-focused reps by about 3-1. A large majority of the newspapers sharing data with us reported that they had implemented a digital sales training program and had made it a priority to hire sales people with digital experience. But the sales force remains more focused on print, reflecting the fact that that print ad revenue, which is shrinking, still makes up the bulk of the overall revenue (on average 92% in our study’s sample).

Newspaper executives described an industry still caught between the gravitational pull of the legacy tradition and the need to chart a faster digital course. A number of them worried that their companies simply had too many people-whether it be in the newsroom, the boardroom or on the sales staff-who were too attached to the old way of doing things.

The research reveals an industry that has not yet moved very far down the road toward a business model to replace the once-thriving legacy model-even though overall newspaper ad revenue has fallen by more than half in just a few years. The industry has pushed back against those losses by increasing the price of subscriptions. Even with that, overall newspaper revenue is down by more than 40% in the last decade.

But researchers also found a strong sense of purpose among the executives leading this industry, business people who see the survival of newspapers as important to civil society, who have their eyes open about where the news industry is headed and who recognize the problems inside their own institutions.

This effort to examine the newspaper industry’s search for a new business model involved several layers of reporting and several different research instruments over a period of 16 months. That began with a series of discussions with a dozen major newspaper companies that began in late 2010. Ultimately, six companies representing 121 papers agreed to share detailed information from individual newspapers. In 2011, there were site visits to conduct lengthy interviews with executives at those companies in order to get their input about how to gather that data. Based on those meetings, the Project for Excellence in Journalism, in conjunction with Princeton Survey Research Associates International, developed 60 questions or data categories for each paper to fill out relating primarily to digital advertising. Thirty-eight newspapers at those six companies, representing about one-third of their properties, provided the data with the understanding that it would be “anonymized,” meaning that no papers or companies would be named in our reports. The study did not ask about digital subscriptions or paywalls, leaving that for the future, because the number of papers that have moved in that direction is still small and, in many cases, not enough time has elapsed to draw conclusions.

Once researchers analyzed the data, we conducted follow-up interviews in early 2012 with executives at the six participating companies and at seven additional companies. Those 13 companies-nine private and four public-comprise 330 daily papers, or 24% of the U.S. daily English-language papers currently in existence. We shared the findings with those executives, asked whether the data reflected what was happening throughout their companies and what the numbers said about where the industry is now and where it is heading.

One other feature of this study, given that data are broken out by individual papers, is that it allows researchers to see more than the usual anecdotal sense of what is occurring at smaller papers.

There are roughly 1,350 surviving U.S. English-language daily newspapers, down from about 1,400 five years ago. The vast majority of these papers are smaller, less than 25,000 circulation. There are 70 papers remaining in the U.S. with circulations more than 100,000.

The sample of papers that provided detailed data also was geographically spread. Eight papers are located in the West, eight in the Midwest and 16 across the South, from Florida to Texas. Six more are from the Northeast. Nineteen of the papers were published in communities with a population of less than 50,000, 12 of them came from communities with a population between 50,000 and 100,000 and seven originated in cities with populations more than 100,000.