The uneasy ceasefire in eastern Ukraine, punctuated by almost daily fighting between separatists and government forces, posed a major challenge to the Pew Research Center as we set about conducting a new public opinion survey in that country. As always, our first priority was the safety of interviewers and respondents, who can both be at risk when it comes to face-to-face surveys in a conflict zone.

In the end, we decided to proceed with the survey, but not to conduct surveys in Luhans’k and Donets’k, due to insecurity, and Crimea, due to concerns that interviewers might be harassed or detained for asking local residents politically sensitive questions.

We only made this decision after revisiting our 2014 survey results and assessing the impact of excluding Luhans’k, Donets’k and Crimea (the survey last year included these regions; see here for an in-depth discussion of challenges we faced a year ago). Did the exclusion of these regions fundamentally alter our 2014 analysis? Would it be worthwhile to survey Ukraine in 2015 without Luhans’k, Donets’k and Crimea?

Our analysis of the 2014 Ukraine survey results indicated that excluding the three regions mainly impacted questions about the United States and Russia. In other cases, the absence of these regions affected the intensity of some attitudes, but did not change the overall direction or substance of public attitudes on such questions as territorial unity, government performance or even relations with the EU. At the same time, even without Luhans’k, Donets’k and Crimea, the 2014 survey captured the east-west divide in public attitudes that was central to our analysis last year.

Assessing the Impact of Excluding Donbas and Crimea

Luhans’k and Donets’k, collectively known as the Donbas region, together with Crimea, are home to approximately 20% of Ukraine’s total population. Perhaps more importantly, roughly half the country’s Russian minority population (51%) lives in these three areas. In the 2014 survey, 77% in Donbas and Crimea spoke only Russian on a daily basis, compared with 18% in the rest of Ukraine. Similarly, 42% in Donbas and Crimea identified their nationality as Russian. Just 10% in the rest of Ukraine said the same. For these reasons, we did not take lightly the decision to alter our survey coverage between 2014 and 2015. The map below shows the location of Donbas and Crimea, and the remaining oblasts or regions that make up the country’s eastern and western regions.

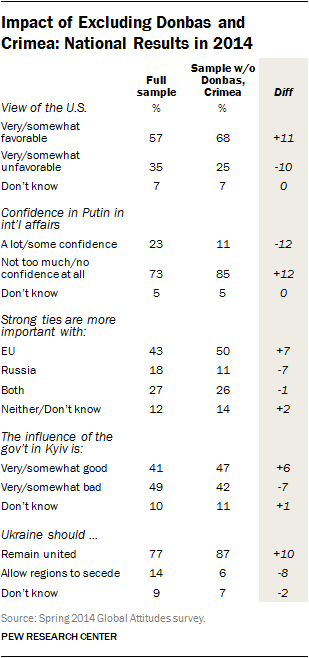

For our evaluation, we compared results from the 2014 survey with and without Luhans’k, Donets’k and Crimea in the sample. For the most part, excluding these regions did not lead to substantial differences in the 2014 survey. Across all substantive questions, the difference between the two samples in any given category ranges from zero to 12 percentage points. The median difference across all questions is one point.

The questions with larger differences are on the topics of Western nations, Russia and the crisis. The table to the right shows the differences on some of the major findings from the 2014 survey report. Overall, when the Donbas region and Crimea are excluded, the national results are more favorable toward Western countries and leaders, less favorable toward Russia and President Vladimir Putin, and less supportive of allowing regions to secede.

For example, in the full national sample, 23% had confidence in Putin to do the right thing in world affairs. When we exclude Donbas and Crimea, this percentage drops to 11%. Similarly, while 77% of the full sample supported Ukraine remaining one, unified country, a larger majority (87%) says the same when Donbas and Crimea are excluded from the sample.

Nonetheless, even without Donbas and Crimea, the heart of the story is the same: Ukrainians generally preferred Western nations to Russia, were divided over their national government, and supported unity rather than secession.

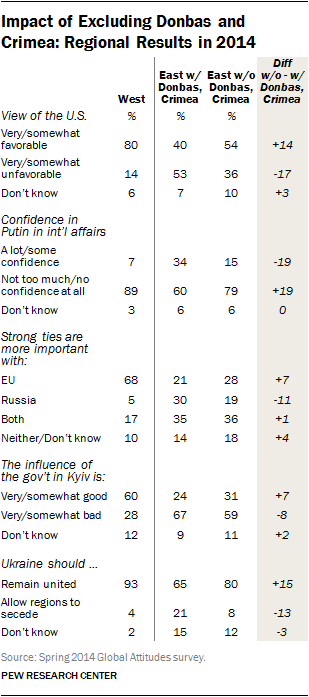

Another important component to the analysis of Ukrainian public opinion is the regional divide between the west and east. Luhans’k, Donets’k and Crimea comprise more than a third of the population (36%) that we defined as eastern Ukraine in 2014. In addition, last year we found substantial differences between east and west Ukraine.

Similar to the national results, our analysis revealed that, for the most part, excluding Donbas and Crimea from the sample has little impact on the results. The differences between the eastern sample with and without Donbas and Crimea range from zero to 18 points in any given category. The median difference across all questions is 1 point.

Not surprisingly, the east without Donbas and Crimea is more favorable toward Western powers, less favorable toward Russia and Putin, and less supportive of secession. Some of these differences are quite substantial. With Donbas and Crimea included, 40% of eastern Ukrainians have a favorable view of the U.S. Without these disputed areas, positive ratings of the U.S. rise to 54% in the east. However, as was true for the national results, on the whole, we find a similar story about attitudes in the east, even without Donbas and Crimea. Majorities still expressed no confidence in Putin and said Ukraine should remain united. In addition, opinions on these questions continued to show a strong east-west divide, despite the absence of Donbas and Crimea.

From our evaluation, we find that the Donbas region and Crimea are distinctive from the rest of Ukraine, and even from the rest of eastern Ukraine, on some key questions. For this reason, it is important to keep in mind that the results of our 2015 survey, which excludes Donbas and Crimea, are likely different than they would be if we had been able to survey in these areas. Nonetheless, our analysis indicates that the broader story about what Ukrainians think about Russia, Western powers, and the future of their country remains largely the same, even without Donbas and Crimea included in the survey.