In recent years, the U.S. government has ramped up spending and staffing on immigration enforcement at the U.S.-Mexico border and in the nation’s interior. Some of its enforcement actions have a particular impact on Mexican immigrants, who constitute a majority (58%) of nation’s unauthorized immigrants (Passel and Cohn, 2011). In addition, a growing number of states have enacted their own immigration enforcement programs.

Appropriations for the U.S. Border Patrol within the Department of Homeland Security (DHS)—only a subset of all enforcement spending, but one especially relevant to Mexican immigrants—more than tripled from 2000 to 2011, and more than doubled from 2005 to 2011 (Rosenblum, 2012). The federal government doubled staffing along the southwest border from 2002 to 2011, expanded its use of surveillance technology such as ground sensors and unmanned flying vehicles, and built hundreds of miles of border fencing.

Federal authorities also changed their tactics in recent years, and some changes have been aimed particularly at Mexican border crossers. Many Mexicans caught at the border who in earlier years would have been just sent home instead are repatriated under the “expedited removal” process, which carries a minimum penalty of not being allowed to seek a visa for at least five years.

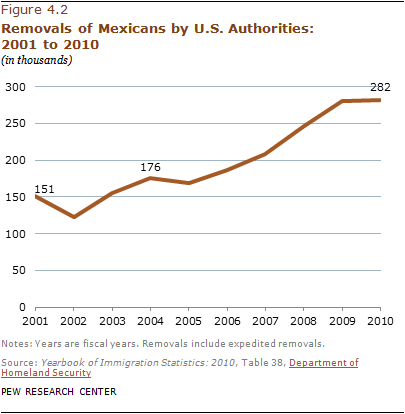

That change is part of the “enforcement with consequences” strategy begun in 2005, under which the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Justice also have increased the share of unauthorized border crossers charged with criminal offenses related to immigration laws. The number of Mexicans removed for criminal offenses rose 65% from 2008 (77,531) to 2010 (127,728), at a time when non-criminal removals declined (169,732 in 2008 to 154,275 in 2010).

As part of the same strategy, the Border Patrol has taken new steps to try to disrupt immigrant smuggling operations. These include sending apprehended border crossers home at locations far from their entry points, to make it more difficult for them to contact smugglers who previously helped them (Rosenblum, 2012).

At the state level, omnibus immigration legislation modeled after an Arizona law that included provisions intended to reduce unauthorized immigration was passed in 2010 by Alabama, Georgia, Indiana, South Carolina and Utah, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures. These laws include provisions requiring law enforcement officials to verify the immigration status of those stopped for other reasons and prohibiting the harbor or transport of unauthorized immigrants. All have been challenged in court, and the U.S. Supreme Court is to hear arguments about the Arizona law (known as SB 1070) on April 25, 2012.

Enforcement Statistics

Government enforcement statistics indicate that the number of Mexicans who agree to be sent home without a formal removal order has declined markedly, a possible sign of lower flows.

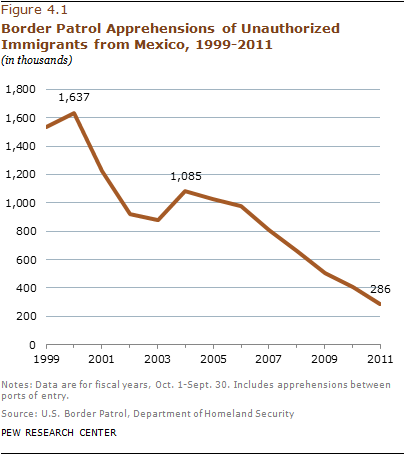

According to data from the Department of Homeland Security, the number of apprehensions of unauthorized Mexican immigrants by the U.S. Border Patrol—more than 1 million in 2005—fell to just 286,000 in 2011. (Note that some people are apprehended more than once.) Border Patrol apprehensions of all unauthorized migrants most recently peaked in 2000, and now are at their lowest level since 1971.

Another U.S. government measure that shows similar trends is the number of unauthorized immigrants who agree to return to their home countries after apprehension without a removal order. The vast majority of these “returns,” in government parlance, are from Mexico. As with apprehensions, this number peaked in 2000, at nearly 1.7 million, declined from 2001 to 2003, rose to about 1 million a year from 2004 to 2006, and has declined since then. In 2010, of 476,405 immigrants repatriated this way, 354,982 (75%) were Mexican, according to Department of Homeland Security statistics.

However, there has been a notable rise in migrants sent home with an order of removal. The number of Mexicans sent home by U.S. authorities via deportation or the expedited removal process rose by two-thirds from 2005 (169,000) to 2010 (282,000). Total removals showed no clear trend earlier in the decade.

On another measure tracked by DHS, trends indicate that fewer migrants may be making multiple attempts to cross the border without authorization. This measure is based on a database of fingerprints that, according to a recent Congressional Research Service report, has been in full use by the Border Patrol since 2005. According to Border Patrol data compiled in the report, there has been a decline in the percentage of apprehended unauthorized migrants who had been caught once before in the same fiscal year. The percentage peaked in 2007 and fell to its lowest level (20%) in the 2011 fiscal year, the report said (Rosenblum, 2012).

A somewhat similar trend is seen in a Mexican government survey of migrants who were apprehended and sent home by U.S. authorities (Encuesta sobre Migración en la Frontera Norte). According to data analyzed by the Pew Hispanic Center, 90% of Mexican immigrants sent home by U.S. authorities in 2010 after being in the U.S. for less than a week say they had never been apprehended before. The share of those immigrants apprehended for the first time went up sharply from 1995 (70%) to 2000 (81%), then generally rose through the subsequent decade.