How we did this

This analysis focuses on views of diversity, ethnic and religious minorities and refugees and migrants across 11 emerging economies. This report also includes demographic analysis comparing across these different groups, as well as regression analysis that examines how regular interaction with people of different backgrounds relates to attitudes about diversity.

For this report we surveyed 28,122 people across 11 different emerging economies. All interviews occurred from September to December 2018 and were conducted face-to-face in the language or languages appropriate for each country. Here are the questions used for the report, along with responses and survey methodology.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, borders around the world have been sealed, presenting challenges for international migrants and asylum seekers. And the virus appears to be fueling the flames of existing ethnic and religious cleavages. But results of a Pew Research Center survey conducted in late 2018 in 11 emerging economies highlights that, even prior to the novel coronavirus outbreak, many countries were grappling with the challenges that changing demographics and diversity bring to their countries – both via immigration and because of existing religious and ethnic cleavages.

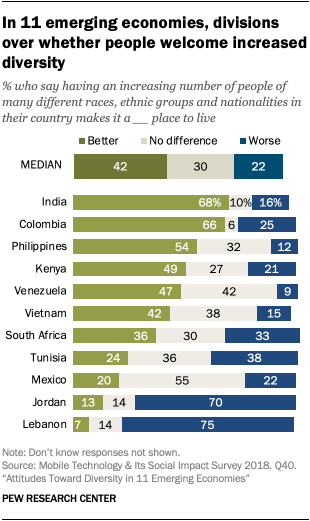

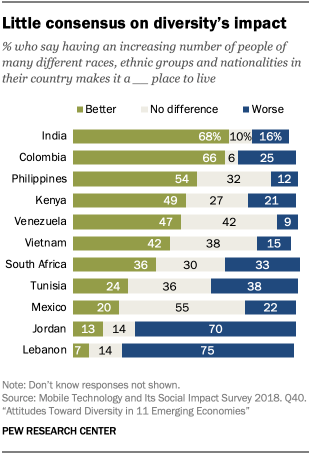

Across the 11 countries surveyed, more said their countries are better off thanks to the increasing number of people of different races, ethnic groups and nationalities who live there (median of 42%) than said their country is worse off (22%), and a large minority said these changes make no difference (30%).

But there was significant variation across the countries studied. For example, in Jordan and Lebanon, both heavily affected by the Syrian refugee crisis, seven-in-ten or more said their country has been made worse by increasing diversity. In contrast, around half or more in Kenya (49%), the Philippines (54%), Colombia (66%) and India (68%) said their country is improved by these demographic changes. In most countries surveyed, people who interact more with those who are different from them – whether religiously, ethnically or racially – tended to be more positive toward societal diversity.

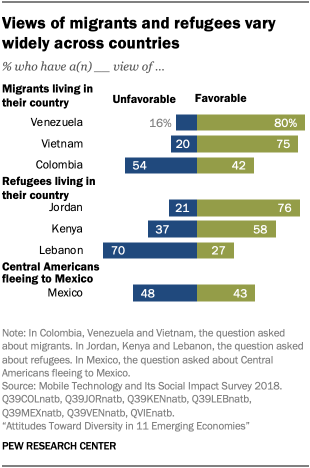

These overarching views about diversity in the country are mirrored in people’s attitudes toward migrants or refugees living in their country. In Lebanon, Jordan, Kenya and Mexico, people were asked whether they had favorable views of refugees living in their country, while in Colombia, Venezuela and Vietnam they were asked about migrants.1 Across these seven countries, those who had more positive views of particular migrant or refugee groups were also more likely to say increasing levels of diversity in the country are good.

Although this relationship is consistent across the countries in the study, views of refugees or migrants vary markedly across the countries surveyed. For example, in Mexico, Colombia and Lebanon, around half or more rated refugees or migrants unfavorably. In recent years, both Mexico and Colombia have seen a surge of migrants fleeing difficult conditions in other Latin American nations. Mexico has seen a surge of migrants from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras (collectively known as the Northern Triangle) arriving at its northern border with the United States. Similarly, Colombia has seen a recent increase in the number of migrants from neighboring Venezuela, following political turmoil in the country. And Lebanon has been the largest host of Syrian refugees per capita in recent years, with an estimated total of 1 million.

By contrast, in Kenya, Jordan, Vietnam and Venezuela, around half or more rated migrant and refugee groups favorably.

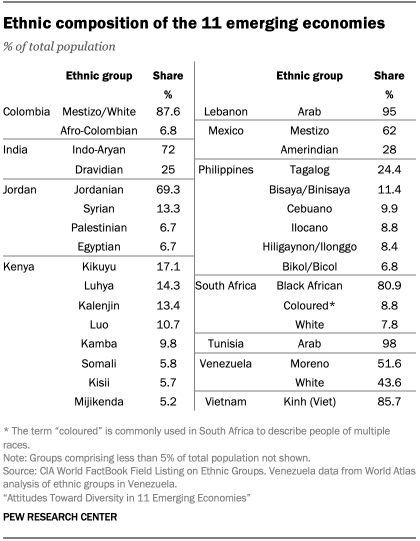

Many of the 11 countries polled also have other important historic racial, ethnic and religious cleavages that may factor into how people view diversity in their country, separate from issues of migration and refugees. In order to capture these dimensions, separate questions were asked in each country depending on the particular context. For example, in India, people were asked their views of Hindus and Muslims; in Kenya, their opinion of some of the larger tribes, including the Kikuyu and the Luo; and in South Africa, their views of different racial groups.2

The 11 countries in this survey were chosen based on a number of key criteria, including their middle-income status, that they contain a mix of people with different levels of technological ownership, and their high levels of internal or external migration, among others.

Because of the unique cultural contexts in each of the 11 countries surveyed, we asked favorability of different groups in each country. We worked with local vendors in each country to ensure that we were asking about important and social divisions, where feasible. In some countries, we asked only about religious or ethnic groups, in others only about refugees or migrant groups, and in some, we asked about both. Below is a list of the groups for which favorability was asked in each country:

Colombia: Migrants living in Colombia India: Hindus, Muslims Jordan: Refugees living in Jordan, Muslims, Christians Kenya: Refugees living in Kenya, people in the Luo tribe, people in the Kikuyu tribe, people in the tribe of the respondent (if different) Lebanon: Refugees living in Lebanon, Sunnis, Shiites, Christians Mexico: Central Americans fleeing to Mexico Philippines: Muslims, Christians South Africa: Black people, white people, coloured people (a term commonly used there to describe people of multiple races) Tunisia: Sunnis, Shiites Venezuela: Migrants living in Venezuela Vietnam: Migrants living in Vietnam

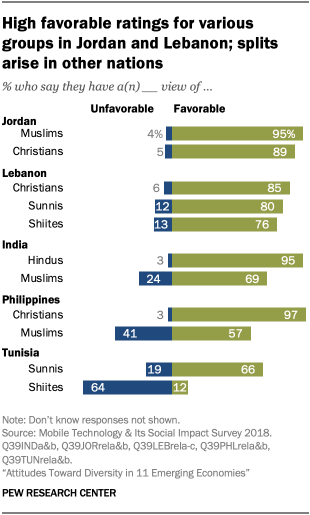

Generally, most people had relatively positive views toward nearly all religious, racial and ethnic groups asked about. For example, when it comes to religious groups, a majority of Lebanese had favorable views of Christians, Sunnis and Shiites alike. The same was true in India of Hindus and Muslims, as well as in the Philippines of Christians and Muslims. Similarly, when it comes to racial and ethnic groups, Kenyans had favorable views of both the Luo and the Kikuyu, and South Africans had favorable views of white, coloured and black South Africans (Note: The term “coloured” is commonly used in South Africa to describe people of multiple races. It is used throughout this report to reflect survey question wording.)

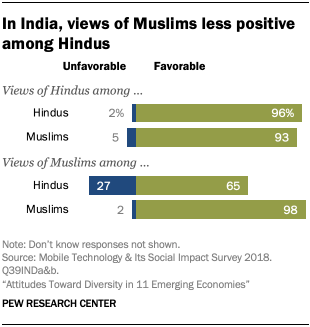

Despite these overall positive opinions, in several instances, people who are members of a particular religious, racial or ethnic group had significantly more favorable views of their own group than they did of groups to which they do not adhere or belong.3 For example, in India, Hindus were much less likely to have a favorable view of Muslims (65%) than were Muslims themselves (98%).

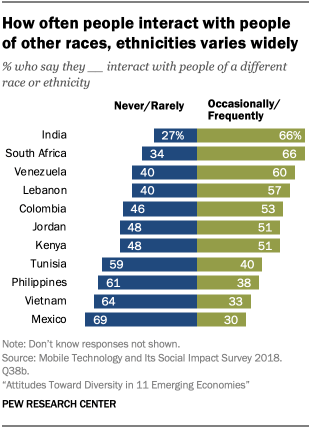

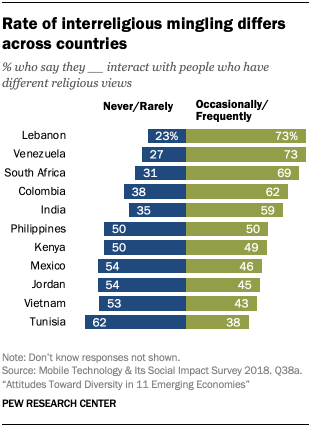

The regularity with which people had contact with those who are different from them also varied markedly across the countries surveyed. In some countries, for example, people said they frequently or occasionally interact with people of other racial or ethnic groups – ranging from a high of about two-thirds who said they did so in India and South Africa to a low of 30% in Mexico who said the same. Regularly interacting with people of other religions, too, varied a great deal; Lebanese, for example, were very likely to interact with people who hold different religious views (73%) while Tunisians were much less likely to do so (38%) – which may reflect the religious composition of the two countries.

Generally, more contact is related to more positive opinions of other racial, ethnic and religious groups within a given society – as well as more favorable views of increasing diversity, more broadly. For example, people who said they regularly interact with those who hold different religious views than they do tend to see all religious groups within the society in more positive terms and to think that increasing diversity in their country is a good thing. The same is true when it comes to interactions with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds. 4

These are among the major findings from a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 28,122 adults in 11 countries from Sept. 7 to Dec. 7, 2018.

Emerging economies diverge on whether increasing diversity is good or bad for their country

Throughout the 11 emerging economies surveyed, views on increasing diversity vary widely.5 Clear majorities in India and Colombia said an increasing number of people of many different races, ethnic groups and nationalities in their country makes it a better place to live. About half or more in the Philippines (54%) and Kenya (49%) agreed, though roughly a third in these countries said that increasing diversity makes no difference. (For comparison, 58% of Americans said these changes made the U.S. a better place to live when last asked in 2018.)

In Venezuela, Vietnam and South Africa, there was no clear consensus on the impact of diversity. While 47% of Venezuelans said having more people of different backgrounds makes their country a better place to live, 42% said this makes little difference. A similar split exists in Vietnam (42% better, 38% no difference). But very few in either of these countries saw diversity making their country worse. In South Africa, there exists a three-way split, with about a third saying more diversity doesn’t make much of a difference to the quality of life in their country. Roughly four-in-ten black South Africans (38%) said that an increasing number of people of diverse backgrounds makes the nation a better place to live, higher than both white (31%) and coloured or multiracial (27%) South Africans.

Mexico stands out as the only country where a majority said increasing the number of people from differing ethnic and racial backgrounds makes no difference to their country. Many Tunisians (36%) also said this, though 38% thought this makes their country worse.

At least seven-in-ten in Jordan and Lebanon said having more people from different races, ethnicities and nationalities makes their country worse.

In Colombia, Kenya, South Africa and Tunisia, younger people were more likely to say increasing diversity makes the country a better place to live. For example, 72% of Colombians under the age of 30 said that more diversity improves their country, compared with 58% of those ages 50 and older. In three countries, those with more education were also more likely to say increasing diversity is a positive.6

Negative views of refugees and migrants in some nations – but those who interact more with people of diverse backgrounds are more positive

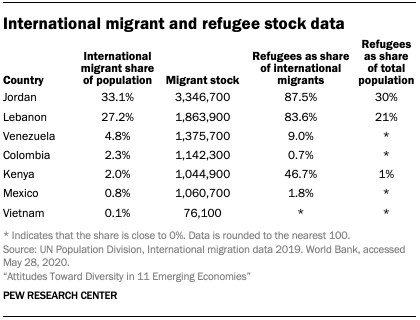

The estimated number of migrants and refugees varies significantly among the 11 countries surveyed, ranging from a low of 60,000 people in 2017 in Tunisia to a high of 5,190,000 people in India in the same year. And, across the seven countries where people were asked specifically about their opinions of migrants living in their country (Colombia, Venezuela and Vietnam) or about refugees (Jordan, Kenya Lebanon and Mexico), opinion of these groups, too, varied markedly.

Part of these cross-country differences may stem from differences in which group people were asked about, given that past Pew Research Center analysis has shown that people tend to express much more support for taking in refugees fleeing violence and war than for immigrants moving to their country. Still, even across the three countries asked specifically about refugees – Jordan, Kenya and Lebanon – opinion differed substantially. For example, 76% of Jordanians had a favorable view of refugees living in their country, compared with 58% of Kenyans and 27% of Lebanese.

The same is also true when it comes to views of migrants. Whereas eight-in-ten Venezuelans had a positive view of migrants living in their country and three-quarters of Vietnamese said the same, only 42% of Colombians felt this way.

Most in Lebanon have negative views of refugees in their country

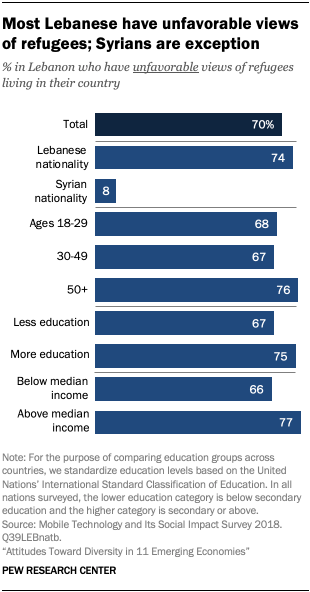

Lebanon – the country where views of diversity were most negative – has been heavily affected in recent years by Syrian refugees. It is the country that hosts the highest number of Syrian refugees per capita, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), having taken in around 1 million refugees in a country with fewer than 7 million people.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting lockdown restrictions placed on Syrian refugees in Lebanon, public sentiment about refugees in Lebanon was largely negative: a 70% majority had an unfavorable view of refugees, including 41% who had very unfavorable opinions. Though age, education and income levels all played a role in views of refugees, majorities across each of these demographic groups held negative opinions. And when it came to religion, Sunni Muslims (60%) were less likely to have unfavorable opinions of refugees than Shiite Muslims (71%) or Christians (83%).

Jordanians are broadly positive toward refugees in their country

In Jordan, public attitudes about refugees are complex. Although Jordanians were more likely to say having increasing numbers of people of other races and nationalities makes their country a worse place to live, they nonetheless held largely positive views of the refugees living within their boundaries.

Part of this may stem from the fact that Jordan has two large refugee populations – one of which has been in the country for decades, the other of which is relatively new.7 The country is home to a large number of Palestinian refugees, many of whom entered the country following the crises during the mid-20th century. Additionally, around 1.3 million Syrians have sought refuge in Jordan since the start of the Syrian refugee crisis in the early 2010s, including over 671,000 who registered as refugees with the UNHCR.

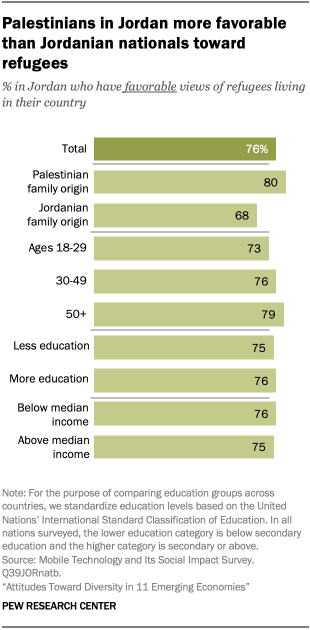

While roughly three-in-four Jordanians had favorable views of refugees when surveyed, they vary by nationality and age. According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency, over 2 million Palestinian refugees live in Jordan, comprising about 20% of Jordan’s population. People in Jordan who self-identified as having a Palestinian family origin were significantly more likely than those who identified as Jordanian to have favorable views of refugees living in the country, with eight-in-ten sharing positive sentiments.

Older adults in Jordan were more likely than younger adults to have favorable views of refugees. Roughly eight-in-ten (79%) of those 50 and older had favorable views of refugees living in Jordan, while 73% of younger adults said the same.

Kenyans tend to have favorable opinions of refugees in their country

Kenya is home to more refugees than almost any other country in Africa, with most refugee and asylum seekers in the country hailing from Somalia and South Sudan. Some of the largest refugee camps in Kenya, which house many people from these neighboring countries, have been operating since the early 1990s.

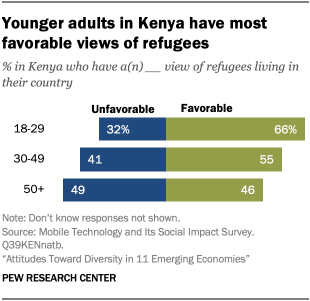

In Kenya, where around half (49%) said that an increasing number of people with different backgrounds makes their country better, views of refugees living in the country were largely positive. A roughly six-in-ten (58%) majority of Kenyan adults had favorable views of refugees.

Younger Kenyans were more favorable than older Kenyans toward refugees. Around two-thirds of adults ages 18 to 29 had favorable views of refugees living in the nation, compared with less than half of those 50 and older (46%). Additionally, those with a secondary education or above were more likely than those with less education to have positive views of refugees (65% vs. 56%, respectively).

Mexicans and Colombians see migrants in their country in negative light

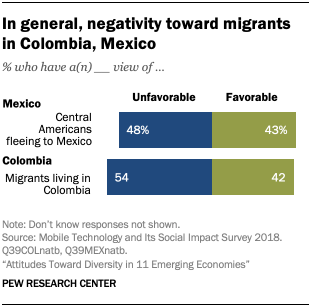

Colombians generally saw increasing numbers of people of different races and ethnicities to be a good thing for their country, and Mexicans tended to think it makes no difference. Nonetheless, migrants in both countries were seen in a somewhat negative light.

Mexico has recently experienced increased immigration from Central America, and the Mexican government apprehended nearly 92,000 migrants in the first seven months of fiscal 2019. Against this backdrop, around half (48%) of Mexicans gave unfavorable ratings to Central Americans fleeing to Mexico. Younger people had more favorable views of Central American migrants in Mexico than those 50 and older. Regardless of gender, income or level of education, Mexicans tended to be slightly more negative than positive.

Colombia has received more than 1 million Venezuelan immigrants in recent years since political and economic unrest began escalating under current Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro. Amid this influx, more than half of Colombian adults (54%) said they held an unfavorable view of migrants in Colombia; 42% had a favorable opinion. Younger Colombians were more likely than their older counterparts to have favorable views of people from other countries who live in Colombia.

Interacting with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds is uncommon in some countries

In some countries included in this survey, we also asked about domestic racial or ethnic divides. This dynamic may be a feature of everyday life for many in countries like Kenya, where ethnic fractionalization is high, but perhaps less salient in places like Vietnam, where the population is more ethnically homogenous. Results of the survey indicate that across the 11 emerging economies, the regularity with which people of different races or ethnicities interact with one another can vary widely.

More than half in India, South Africa, Venezuela, Lebanon and Colombia said they occasionally or frequently interact with people of ethnic groups or races different than their own. On the other hand, majorities in Tunisia, the Philippines, Vietnam and Mexico reported that they rarely or never have these kinds of experiences. Jordanians and Kenyans were about evenly divided.

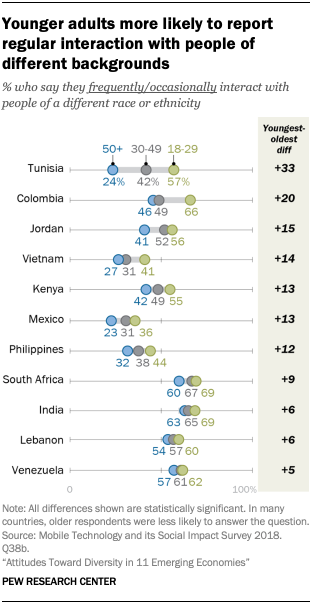

In all countries surveyed, younger adults were more likely to interact with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds than their older counterparts.

This difference was most pronounced in Tunisia, where roughly one-in-four adults ages 50 and older (24%) said they frequently or occasionally interact with people of a different race or ethnicity, while a majority of 18- to 29-year-olds (57%) said the same, a 33-point difference.

In all countries except for Venezuela, men were more likely than women to describe having contact outside their own ethnic or racial group. The widest gaps exist in Mexico (14 percentage points) and Colombia (13 points). In many countries, women were also more likely than men to say they never interact with anyone of a different race or ethnicity; roughly a third or more of women said this in Mexico (46%), Tunisia (45%), Jordan (39%), Vietnam (36%), Colombia (32%) and the Philippines (30%). Women in some countries were also less likely than men to answer the question.

And in 10 of 11 countries, those with higher levels of education were more likely to say they regularly interact with people of other ethnicities or races. (In some countries, those with less education were less likely to answer the question.)

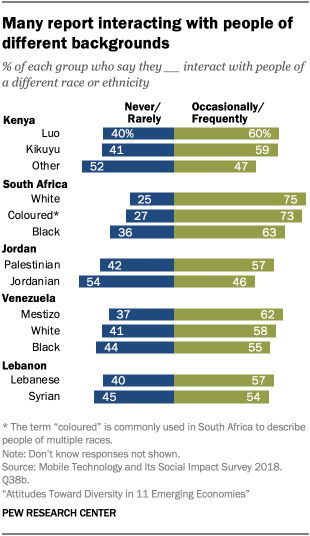

In some countries, the regularity with which people interact with those of different racial or ethnic groups varied based on their own racial or ethnic identity. For example, in South Africa, where the majority of the population is black, 75% of white South Africans (who are in the minority) reported interactions with people of different racial and ethnic groups, while roughly six-in-ten black adults (63%) said the same.

A similar pattern existed in Jordan, where close to 70% of the nation’s population identifies as Jordanian and self-identified Palestinians make up roughly 7% of the population. A little more than half of Jordanians (54%) reported never or rarely interacting with people of different backgrounds, while a majority of Palestinians (57%) said they occasionally or frequently interact with people of different backgrounds.

More than half of both Lebanese (57%) and Syrian (54%) adults in Lebanon reported having regular interactions with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Interacting with people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds is related to more positive views of migrants and refugees

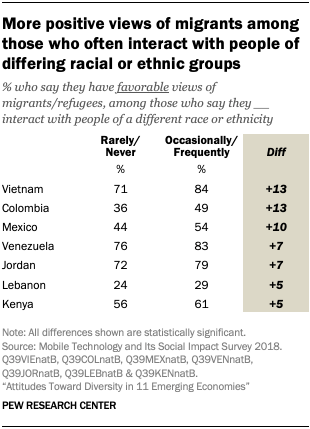

Across the seven countries surveyed on favorability of migrants and refugees, interactions with people of racial or ethnic groups different than one’s own was related to less negative feelings toward refugees and migrants.8

For example, Colombians who said they often interact with people of other races or ethnicities were split on their views of migrants living in Colombia: 49% were favorable, compared with 48% who held an unfavorable view. However, this is still significantly more positive than the attitudes of those who said they rarely or never interact with people of other races: Only about a third of this group had positive views of migrants in Colombia, a 13 percentage point difference.

Similarly, more than half of those in Mexico who reported occasional or frequent exchanges with those of other races and ethnicities (54%) had a favorable view of migrants, compared with just 44% of those who reported rarely or never interacting with people of different races, a 10-point difference. Smaller but consistent patterns in the same direction were also seen in Venezuela, Jordan, Lebanon and Kenya.

Results of statistical modeling also indicate a strong relationship in these countries between views of diversity and how often one interacts with people of other backgrounds. Bivariate and multiple regression analyses suggest that more interactions of this nature are tied to individuals increasingly thinking a more diverse populous makes their country a better place to live. Demographic variables, including education and gender, also play a role in shaping these views, though age is not strongly related. This relationship persists across countries even when accounting for other key attitudinal variables, such as trust in the national government or views of the national economic situation. (In regression parlance, we have “controlled” for these factors.) For more about the methodology and for a more detailed presentation of the regression model informing these results, please see Appendix A.

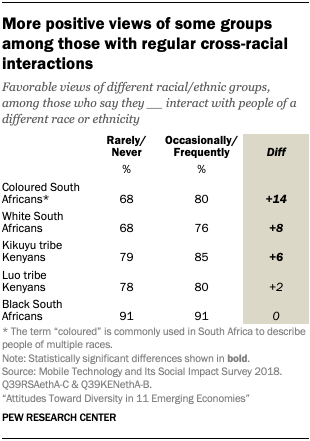

In Kenya and South Africa, people were also asked whether they have favorable opinions of different racial and ethnic groups. In each country, people who are members of a particular racial or ethnic group tended to have more favorable opinions of their own group than of other groups.

In Kenya, for example, majorities had favorable views of both the Luo and Kikuyu tribes, which make up 11% and 17% of the population, respectively. But people who self-identify as Luo tend to have even more favorable opinions of their own tribe than of the Kikuyu, and the same is true when it comes to the Kikuyu tribe and views of the Luo. Similarly, in South Africa, a majority of people had a favorable view of white South Africans, black South Africans and coloured South Africans. But people tended to have more positive views of their own racial group than of others.

In some instances, interactions with people of different backgrounds also contribute to favorable views of people of different racial and ethnic identities. For example, favorability of both coloured and white South Africans is higher among those who report regular interactions with people of different backgrounds.

Those who interact with people of other religious groups have more positive opinions of them

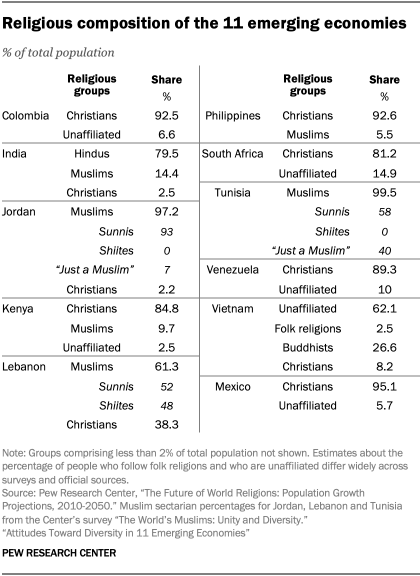

The 11 emerging economies surveyed exhibit a great deal of variation in terms of religious composition that may contribute to people’s views of multiculturalism in their country. For example, some of the countries have roughly nine-in-ten or more adults belonging to one major religious group. Christians play this role in Colombia, Mexico, the Philippines and Venezuela. In Tunisia and Jordan, nearly everyone identifies as Muslim.

Most people in Lebanon identify as Muslim (61%), but this group is split almost evenly by sectarian affiliation – those who say they are Shiite vs. Sunni. Meanwhile, Christians represent about four-in-ten Lebanese adults. Vietnam has the most dispersed religious distribution among the nations surveyed, with 62% not associating with a particular religion, 27% adhering to Buddhism, 7% identifying with Christianity and 3% practicing folk religions.

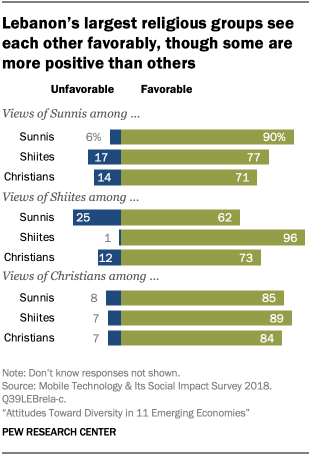

People in five countries – Jordan, Lebanon, India, the Philippines and Tunisia – were specifically asked their opinion of other religious groups in their country, and opinion varies widely across these five nations. In Jordan, where about 97% of the population practices Islam, about nine-in-ten adults or more rated both Muslims and Christians favorably. Similar positivity appeared in Lebanon, with roughly three-quarters or more giving positive reviews to Christian, Sunni and Shiite religious groups.

Bigger divisions appear in three of the other surveyed countries that were asked about various religious groups. Favorable views of Sunni Muslims outpaced that of Shiites by more than five-to-one in Tunisia, where Islam is the official religion but very few identify as Shiite. Likewise, in Christian-majority Philippines, favorable views of Christians were nearly universal (97%) while just 57% said the same of Muslims in their country.

Some of these positive views, though, are contingent on the respondent’s religious affiliation. Take India as an example. While Muslims were seen less favorably than Hindus in the country as a whole, this may in part reflect the fact that Muslims make up only 14% of the Indian population. Among Muslim respondents, 98% had a favorable view of Muslims, whereas among Hindus, favorability was much lower (65%). More than nine-in-ten across both religious groups gave favorable views of Hindus, regardless of how they identified religiously.

Lebanon offers another interesting case study. In 1943, the country gained independence and adopted a confessional-style government that apportioned political positions and parliament seats based on religious affiliation. This system was meant to foster tolerance among Lebanon’s many religious groups, and while the three largest factions tend to view each other favorably, some variance exists in the degree of this goodwill.

Nine-in-ten Lebanese Sunnis rated themselves favorably. At least seven-in-ten said the same among Lebanese Shiites (77%) and Christians (71%) – still mostly positive but lower than the rating Sunnis gave to themselves.

Similarly, almost all Shiites in Lebanon (96%) rated their own group favorably; just 1% said they had an unfavorable opinion. Majorities of Christians also had favorable views of Shiites (73%), as did Sunnis (62%), but this sentiment was felt less universally. In fact, a quarter of Sunnis rated Shiite Muslims unfavorably.

Lebanese Christians tended to receive positive ratings from other religions with a comparable level of enthusiasm as they gave to themselves. More than eight-in-ten Christians held favorable views of Christians (84%), as did similar portions of Sunni (85%) and Shiite Muslims (89%).

Regularity of interaction with people of other religions varies widely

Both the degree to which there is religious diversity in a country – and personal preference – may shape whether people regularly interact with those who have different religious views than their own. Across the 11 emerging economies surveyed, there is a great deal of variation in terms of how often people interact with people of differing faiths.

Majorities in Lebanon, Venezuela, South Africa, Colombia and India said they frequently or occasionally interact with people who have different religious beliefs than they do. On the other hand, in Mexico, Jordan, Vietnam and Tunisia, more than half of adults said these interfaith connections happened only rarely or never. Filipinos and Kenyans were split about the frequency of their exchanges with people of other religions.

In 10 countries, younger adults (ages 18 to 29) were more likely than those ages 50 and older to report regularly interacting with people of different religious views. This includes large gaps in Tunisia (where younger adults were 27 percentage points more likely to say this), Colombia (19 points), Mexico (16 points) and Vietnam (14 points). Those with more education also reported more frequent interactions with people of different beliefs in every country surveyed except Vietnam. In eight countries, men were more likely than women to say they often interact with people from other religions; Venezuelan women bucked this trend and were more likely than their male counterparts to report frequent cross-religious communications.

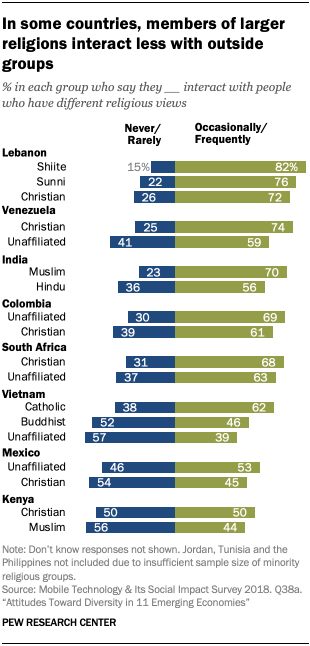

In the countries surveyed with sizable minority religious groups, members of the majority religion tended to interact less with those of other beliefs. For example, Hindus make up about three-quarters of India’s overall population, and they were less likely to say they occasionally or frequently interact with members of other religions compared with Indian Muslims.

On the other hand, the Venezuelan population is approximately 90% Christian and 10% unaffiliated. Yet more Christians (74%) said they often interact with other religious groups, while just 59% of religiously unaffiliated adults said the same.

Vietnam is another interesting case study. Officially an atheist state, most Vietnamese (62%) identify as nonreligious. A majority of unaffiliated people reported infrequent interactions with those practicing other religions. Catholics, who make up less than 8% of the population, described more frequently interacting with those from other faiths (62%).

People who interact more with those of other religious groups also tend to have more favorable opinions

While religious affiliation does affect some groups’ views of nonmembers, the frequency with which they have interactions with those of other religions also plays a role.

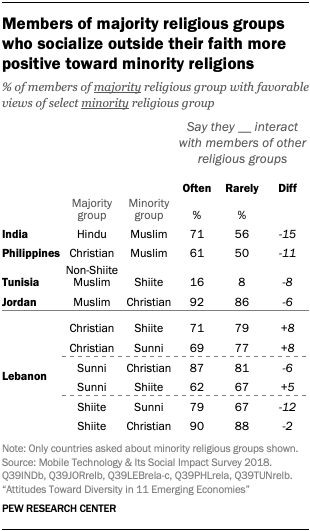

Among Hindus who said they often interact with people outside of their faith, 71% had a favorable view of Muslims. Just 56% of Hindus who reported infrequent contact with people of other religions said the same of Muslims – a 15 percentage point difference.

Among Filipino Christians who said they often interact with members of other religions, 61% gave favorable marks to Muslims, while 50% of those Christians with less frequent cross-religious interactions reported positive views of those in their country who practice Islam. About 93% of Filipinos are Christian, and 6% practice Islam.

Similar disparities exist in Tunisia and Jordan, both overwhelmingly Muslim nations. In Tunisia, where nearly all Muslims identify either as Sunni or “just a Muslim,” Shiites received very little positivity. Among Tunisian Muslims who infrequently interact with those outside their religion, just 8% saw Shiites favorably; those who reported more frequent contact with those of other faiths still gave just 16% favorable marks to Shiites. Meanwhile, overwhelming majorities of Jordanian Muslims rated Christians positively, though slightly more favorable views of Christians were found among those in the Hashemite Kingdom who mingle with other religious groups (92% vs. 86%, respectively).

Lebanon – where Christians outnumber Sunnis and Shiite but no group holds a majority – this pattern does not hold. In fact, Christians who did not report interacting with other religions tended to be more positive toward the other religious groups studied. Sunnis and Shiites showed more mixed results.