Following the coronavirus outbreak, reports of discrimination and violence toward Asian Americans increased. A previous Pew Research Center survey of English-speaking Asian adults showed that as of 2021, one-third said they feared someone might threaten or physically attack them. English-speaking Asian adults in 2022 were also more likely than other racial or ethnic groups to say they had changed their daily routines due to concerns they might be threatened or attacked.19

In this new 2022-23 survey, Asian adults were asked if they personally know another Asian person in the U.S. who had been attacked since the pandemic began.

Asian adults who personally know an Asian person who has been threatened or attacked since COVID-19

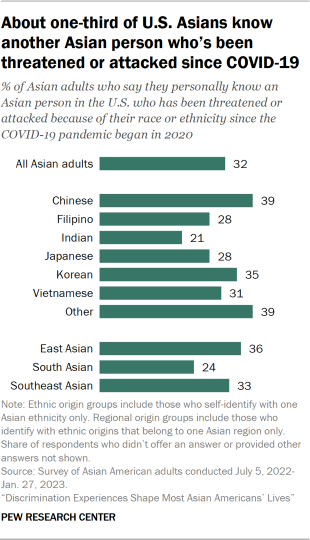

About one-third of Asian adults (32%) say they personally know an Asian person in the U.S. who has been threatened or attacked because of their race or ethnicity since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020.

Whether Asian adults know someone with this experience varies across Asian ethnic origin groups:

- About four-in-ten Chinese adults (39%) say they personally know another Asian person who has been threatened or attacked since the coronavirus outbreak. Similar shares of Korean adults (35%) and those who belong to less populous Asian origin groups (39%) – those categorized as “other” in this report – say the same.

- About three-in-ten Vietnamese (31%), Japanese (28%) and Filipino (28%) Americans and about two-in-ten Indian adults (21%) say they know another Asian person in the U.S. who has been the victim of a racially motivated threat or attack.

Additionally, there are some differences by regional origin groups:

- Overall, similar shares of East and Southeast Asian adults say they know another Asian person who’s been threatened or attacked because of their race or ethnicity (36% and 33%, respectively).

- A somewhat smaller share of South Asian adults say the same (24%).

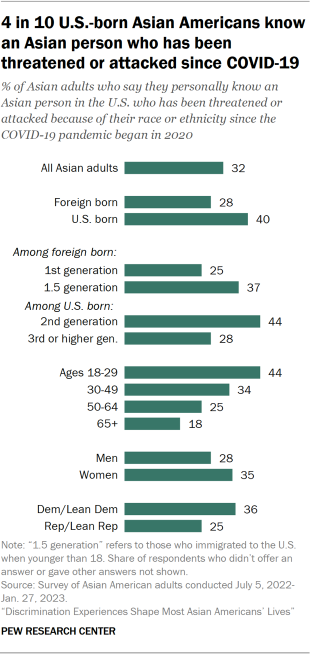

There are also differences across nativity and immigrant generations:

- U.S.-born Asian adults are more likely than Asian immigrants to say they know another Asian person who has been threatened or attacked during the COVID-19 pandemic (40% vs. 28%, respectively).

- Among immigrants, those who are 1.5 generation – those who came to the U.S. as children – are more likely than the first generation – those who immigrated as adults – to say they know someone with this experience (37% vs. 25%).

- And among U.S.-born Asian Americans, 44% of second-generation adults say this, compared with 28% of third- or higher-generation Asian adults.

Whether Asian Americans personally know another Asian person who was threatened or attacked because of their race or ethnicity since the beginning of the pandemic also varies across other demographic groups:

- Age: 44% of Asian adults under 30 years old say they know someone who has been threatened or attacked during the pandemic, compared with 18% of those 65 and older.

- Gender: Asian women are somewhat more likely than men to say they know an Asian person in the U.S. who has been threatened or attacked during the COVID-19 pandemic (35% vs. 28%, respectively).

- Party: 36% of Asian Democrats and Democratic leaners say they know another Asian person who has been threatened or attacked because of their race or ethnicity, higher than the share among Republicans and Republican leaners (25%).

Heightened anti-Asian discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic

These survey findings follow a spike in reports of discrimination against Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic. The number of federally recognized hate crime incidents of anti-Asian bias increased from 158 in 2019 to 279 in 2020 and 746 in 2021, according to hate crime statistics published by the FBI. In 2022, the number of anti-Asian hate crimes decreased for the first time since the coronavirus outbreak, to 499 incidents. Between March 2020 and May 2023, the organization Stop AAPI Hate received more than 11,000 self-reported incidents of anti-Asian bias, the vast majority of which involved harassment, bullying, shunning and other discrimination incidents.

Additionally, previous research found that calling COVID-19 the “Chinese Virus,” “Asian Virus” or other names that attach location or ethnicity to the disease was associated with anti-Asian sentiment in online discourse. Use of these phrases by politicians or other prominent public officials, such as by former President Donald Trump, coincided with greater use among the general public and more frequent instances of bias against Asian Americans.

In their own words: Asian Americans’ experiences with discrimination during the COVID-19 pandemic

In the 2021 Pew Research Center focus groups of Asian Americans, participants discussed their experiences of being discriminated against because of their race or ethnicity during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants talked about being shamed in both public and private spaces. Some Asian immigrant participants talked about being afraid to speak out because of how it might impact their immigration status:

“I was walking in [the city where I live], and a White old woman was poking me in the face saying, ‘You are disgusting,’ and she was trying to hit me. I ran away crying. … At the time, I was with my boyfriend, but he also just came to the U.S., so we ran away together thinking that if we cause trouble, we could be deported.”

–Immigrant woman of Korean origin in late 20s (translated from Korean)

“[A very close friend of mine] lived at [a] school dormitory, and when the pandemic just happened … his room was directly pasted with the adhesive tape saying things like ‘Chinese virus quarantine.’”

–Immigrant man of Chinese origin in early 30s (translated from Mandarin)

Many participants talked about being targeted because others perceive them as Chinese, regardless of their ethnicity:

“I think the crimes [that happened] against other Asian people can happen to me while going through COVID-19. When I see a White person, I don’t know if their ancestors are Scottish or German, so they will look at me and think the same. It seems that they can’t distinguish between Korean and Chinese and think that we are from Asia and the onset of COVID-19 is our fault. This is something that can happen to all of us. So I think Asian Americans should come together and let people know that we are also human and we have rights. I came to think about Asian Americans that they shouldn’t stay still even if they’re trampled on.”

–Immigrant woman of Korean origin in early 50s (translated from Korean)

“Even when I was just getting on the bus, [people acted] as if I was carrying the virus. People would not sit with me, they would sit a bit far. It was because I look Chinese.”

–Immigrant woman of Bhutanese origin in early 30s (translated from Dzongkha)

Amid these incidents, some participants talked about feeling in community and kinship with other Asian people:

“[When I hear stories about Asian people in the news,] I feel like automatically you just have a sense of connection to someone that’s Asian. … [I]t makes me and my family and everyone else that I know that is Asian super mad and upset that this is happening. [For example,] the subway attacks where there was a mother who got dragged down the stairs for absolutely no reason. It just kind of makes you scared because you are Asian, and I would tell my mom, ‘You’re not going anywhere without me.’ We got pepper spray and all of that. But there is definitely a difference because you just feel a connection with them no matter if you don’t know them.”

–U.S.-born woman of Taiwanese origin in early 20s

“[A]s a result of the pandemic, I think we saw an increase in Asian hate in the media. I think that was one time where I realized as an Asian person, I felt a lot of pain. I felt a lot of fear, I felt a lot of anger and frustration for my community. … I think it was just at that specific moment when I saw the Asian hate, Asian hate crimes, and I realized, ‘Oh, they’re targeting my people.’ I don’t know how to explain it exactly. I never really referred to myself just plainly as an Asian American, but when I saw it in that media and I saw people who looked like me or people who I related with getting hurt and mistreated, I felt anger for that community, for my community.””

–U.S.-born woman of Korean origin in late teens

Some connected discrimination during the pandemic to other times of heightened anti-Asian discrimination. For example, one woman connected anti-Asian discrimination during COVID-19 to the period after Sept. 11:

“[T]he hate crimes I’m reading about now are towards Chinese [people] because of COVID, but I remember after 9/11, that was – I remember the looks that people would give me on the subway but also reading the violent acts committed towards Indians of all types, just the confusion – I mean, I say confusion but I mean really they wanted to attack Muslims, but they didn’t care, they were just looking for a brown person to attack. So there’s always something that happens that then suddenly falls on one community or another.”

–U.S.-born man of Indian origin in late 40s