At a time of national debate over health care costs and insurance, a Pew Research Center survey on end-of-life decisions finds most Americans say there are some circumstances in which doctors and nurses should allow a patient to die. At the same time, however, a growing minority says that medical professionals should do everything possible to save a patient’s life in all circumstances.

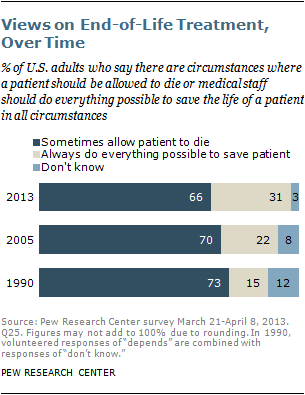

When asked about end-of-life decisions for other people, two-thirds of Americans (66%) say there are at least some situations in which a patient should be allowed to die, while nearly a third (31%) say that medical professionals always should do everything possible to save a patient’s life. Over the last quarter-century, the balance of opinion has moved modestly away from the majority position on this issue. While still a minority, the share of the public that says doctors and nurses should do everything possible to save a patient’s life has gone up 9 percentage points since 2005 and 16 points since 1990.

The uptick comes partly from a modest decline in the share that says there are circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die and partly from an increase in the share of the public that expresses an opinion; the portion that has no opinion or declines to answer the survey question went down from 12% in 1990 to 8% in 2005 and now stands at 3%.

When thinking about a more personal situation, many Americans express preferences for end-of-life medical treatment that vary depending on the exact circumstances they might face. A majority of adults say there are at least some situations in which they, personally, would want to halt medical treatment and be allowed to die. For example, 57% say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment if they had a disease with no hope of improvement and were suffering a great deal of pain. And about half (52%) say they would ask their doctors to stop treatment if they had an incurable disease and were totally dependent on someone else for their care. But about a third of adults (35%) say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to keep them alive – even in dire circumstances, such as having a disease with no hope of improvement and experiencing a great deal of pain. In 1990, by comparison, 28% expressed this view. This modest uptick stems largely from an increase in the share of the public that expresses a preference on these questions; the share saying they would stop their treatments so they could die has remained about the same over the past 23 years.

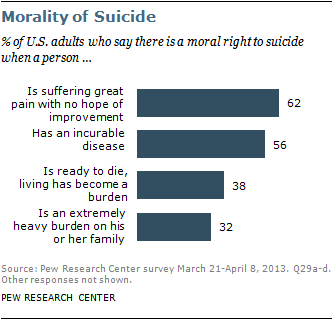

At the same time, a growing share of Americans also believe individuals have a moral right to end their own lives. About six-in-ten adults (62%) say that a person suffering a great deal of pain with no hope of improvement has a moral right to commit suicide, up from 55% in 1990. A 56% majority also says this about those who have an incurable disease, up from 49% in 1990. While far fewer (38%) believe there is a moral right to suicide when someone is “ready to die because living has become a burden,” the share saying this is up 11 percentage points, from 27% in 1990. About a third of adults (32%) say a person has a moral right to suicide when he or she “is an extremely heavy burden on his or her family,” roughly the same share as in 1990 (29%).

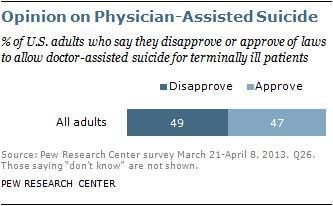

Meanwhile, the public remains closely divided on the issue of physician-assisted suicide: 47% approve and 49% disapprove of laws that would allow a physician to prescribe lethal doses of drugs that a terminally ill patient could use to commit suicide. Attitudes on physician-assisted suicide were roughly the same in 2005 (when 46% approved and 45% disapproved).

Religion and End-of-Life Care

Personal preferences about end-of-life treatment are strongly related to religious affiliation as well as race and ethnicity. For example, most white mainline Protestants (72%), white Catholics (65%) and white evangelical Protestants (62%) say they would stop their medical treatment if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain. (See the chart in Personal Wishes section below.) By contrast, most black Protestants (61%) and 57% of Hispanic Catholics say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in the same circumstances. On balance, blacks and Hispanics are less likely than whites to say they would halt medical treatment if they faced these kinds of situations.

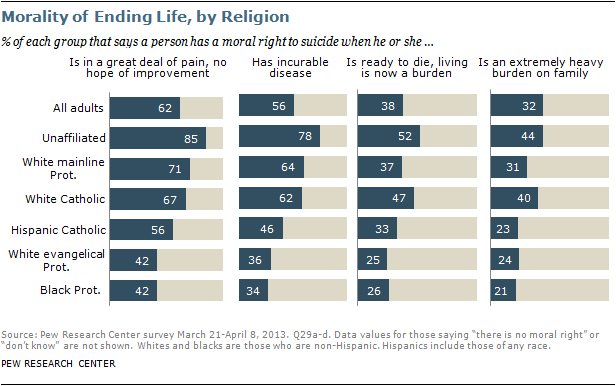

Religious groups also differ strongly in their beliefs about the morality of suicide. About half of white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants reject the idea that a person has a moral right to suicide in all four circumstances described in the survey. By comparison, the religiously unaffiliated, white mainline Protestants and white Catholics are more likely to say there is a moral right to commit suicide in each of the four situations considered. There is a similar pattern among religious groups when it comes to allowing physician-assisted suicide for the terminally ill. (See the chart in Physician-Assisted Suicide for the Terminally Ill section below.)

These are some of the key findings from the Pew Research Center telephone survey, which was conducted on landlines and cellphones from March 21 to April 8, 2013, among a nationally representative sample of 1,994 adults. The margin of error for the survey is plus or minus 2.9 percentage points. For more details, see Appendix A: Survey Methodology.

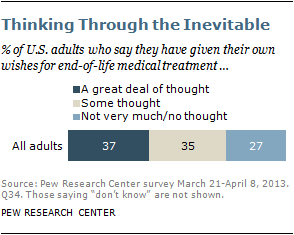

Preparing for End-of-Life Decisions

The share of the total U.S. population that is age 65 and older has more than tripled over the last century, from roughly 4% in 1900 to 14% in 2012. But despite the graying of America, a sizable minority of the populace has not thought about the kinds of medical decisions that people increasingly face as they age. Nearly four-in-ten U.S. adults (37%) say they have given a great deal of thought to their wishes for medical treatment at the end of their lives, and an additional 35% have given some thought to these issues. But fully a quarter of adults (27%) say they have not given very much thought or have given no thought at all to how they would like doctors and other medical professionals to handle their medical treatment at the end of their lives.

Even among Americans ages 75 and older, one-in-four say they have not given very much or any thought to their end-of-life wishes. Further, one-in-five Americans ages 75 and older (22%) say they have neither written down nor talked with someone about their wishes for medical treatment at the end of their lives. And three-in-ten of those who describe their health as fair or poor have neither written down nor talked about their wishes with anyone, according to the Pew Research survey.

There has been only modest change over time in the level of public attention to, and preparation for, end-of-life medical decisions. The share of Americans who report having given a great deal of thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical treatment (37%) is roughly the same as it was in a 2005 Pew Research Center survey and up modestly from 23 years ago, when 28% said they had given a great deal of thought to their wishes. About a third of all adults (35%) say they have put their wishes for end-of-life decisions into writing, whether in an informal document (such as a letter to a relative) or a formal, legal one (such as a living will or health care directive). That share is about the same as in 2005 (34%) and up from about one-in-six (16%) in 1990.1

The vast majority of people who have given a great deal of thought to their own wishes have either written down or talked about their wishes with someone else (88%). Conversely, only about three-in-ten (31%) of those who say they have not given very much or any thought to their wishes have written down or talked about their wishes.

Americans with more education and higher incomes are more likely than those with less education and lower incomes to have communicated their wishes for end-of-life care. Whites are more likely than blacks or Hispanics to have made their wishes known. Those who have not written down or talked about their wishes are more likely than those who have made their wishes known to say they would want doctors and nurses to do everything possible to keep them alive if they were facing a dire medical situation.

Attention to, preparation for and preferences about end-of-life medical treatments also are correlated with age. Younger adults, especially those ages 18-49, are less likely than their older counterparts to have thought about these issues and to have put their wishes for end-of-life treatment in writing. Younger generations also are less inclined to say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment if they were facing a serious illness. Differences in personal preferences among Americans ages 50 and older are relatively muted, however. For example, if faced with an incurable disease and experiencing a great deal of pain, six-in-ten or more of those ages 50-64, 65-74, and 75 and older say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment so they could die, while 22-24% of each age group says they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in those circumstances.

Other findings from the survey include:

- Many Americans have faced end-of-life medical issues through experiences with friends or relatives. About half of adults (47%) say they have a friend or relative who has had a terminal illness or who has been in a coma within the last five years. This experience cuts across most social and demographic groups, including age, gender, education and religious affiliation. And about half of these adults (23% of the general public) report that the issue of withholding life-sustaining treatment arose for their loved one.

- A strong majority of the public (78%) says that a close family member should be allowed to make decisions on behalf of a patient toward the end of life if the patient is unable to communicate his or her own wishes. At the same time, a substantial minority of adults (38%) say that parents have a right to refuse treatment on behalf of an infant born with a life-threatening defect, while 57% say such an infant should receive as much treatment as possible, regardless of the defect.

- In an aging society, Americans see a number of characteristics and functions as important to a good quality of life. About half of adults (49%) rate being able to talk or communicate as extremely important for a good quality of life in older age; similar shares say being able to feed oneself (45%), getting enjoyment out of life (44%) and living without severe, long-lasting pain (43%) are extremely important for a good quality of life in older age. Adults ages 75 and older are less inclined than younger generations to rate seven of the eight characteristics included in the survey as important for a good quality of life.

The rest of this Overview discusses the key findings of the survey in greater detail.

An Aging America With Limited Attention to Preparation for Dying

Advances in health and medicine have helped Americans live longer, with the average life expectancy in the U.S. now 78.7 years.2 Small but steady increases in longevity coupled with stagnant or declining fertility rates over the past several decades have led to a growing elderly population. The share of the total U.S. population (including children and adults) that is age 65 and older has more than tripled over the last century – rising from roughly 4% in 1900 to 14% in 2012 – and is expected to reach about a fifth of the total U.S. population by the year 2060, according to projections by U.S. Census Bureau.3 However, roughly a quarter of U.S. adults (27%) say they have given either no thought or not very much thought to their own wishes when it comes to end-of-life medical treatment.

Nearly half of the general public has at least indirect experience with end-of-life treatment issues: 47% of adults say they have had a close friend or relative facing a terminal illness or in a coma within the past five years, and about a fifth of U.S. adults (23%) report that the question of whether to withhold life-sustaining treatment arose for that person.4 But the share of Americans who say they have given a great deal or some thought to their own wishes for end-of-life medical treatment (37%) is roughly the same as when last tracked in a 2005 Pew Research survey and up only modestly from 1990, when 28% said this.

About a third of adults (35%) say their wishes are written down, whether informally or in a formal document such as a living will or a health care directive. The current share of adults who have put their wishes in writing is about the same as it was in 2005 (34%) and is up sharply from about one-in-six (16%) in 1990.5 Additionally, roughly six-in-ten adults today (62%) say they have talked with someone about their wishes for end-of-life medical treatment.

Personal Wishes

When it comes to personal preferences for end-of-life treatment, public attitudes are far from black and white, with preferences that vary depending on the situation.

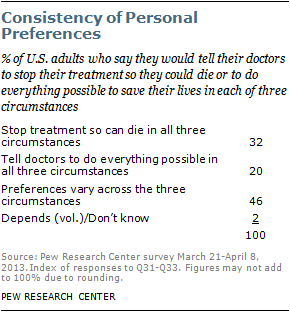

For example, a majority of adults (57%) say they would tell their doctors to stop their medical treatment so they could die if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain, while a sizable minority (35%) say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in that situation. About half of the public (52%) says they would have their doctors stop medical treatment if they faced an incurable disease that made them totally dependent on someone else for care, while 37% say they would pursue all treatment options in such circumstances. And the public is evenly divided about what to do in a situation involving an incurable disease that made it hard to function in day-to-day activities: 46% say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment under those circumstances, while an identical percentage say they would want their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives.

Looking across this set of three scenarios, about a third of adults (32%) consistently say they would tell their doctors to stop medical treatment in all three of these circumstances; a fifth (20%) say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in all three cases, and 46% give differing responses depending on the exact circumstances.

Personal preferences about end-of-life medical treatment have changed only modestly over time. A somewhat greater share of the public expresses a preference on this set of questions today than did so in past years, and a somewhat greater share of adults today say they would do everything possible to save their lives if they had an incurable disease in all three of these circumstances, especially compared with survey findings from 1990. However, the balance of personal preferences has been roughly the same in all three circumstances since 1990.

Personal preferences for medical treatment differ by age. For example, a strong majority of adults ages 50 and older say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment and allow them to die if they were suffering a great deal of pain from an incurable illness. By comparison, 42% of adults under age 30 say they would do the same, and about half (51%) of adults ages 30-49 say they would tell doctors to stop their treatment so they could die.

There are also substantial differences across racial and ethnic groups when it comes to personal choices about medical treatment. Whites are more inclined than either blacks or Hispanics to say they would stop their medical treatment in these kinds of circumstances. For example, about two-thirds of whites (65%) say they would want to be allowed to die if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain, compared with 26% who say they would ask their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives in such circumstances. By contrast, a majority of blacks (61%) and about half of Hispanics (55%) say they would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain.

Personal preferences also tend to differ by religious affiliation. Black Protestants are least inclined to say they would ask their doctors to stop their medical treatment so they could die if faced with an incurable disease and experiencing a great deal of pain; 32% say they would stop treatment, while a majority (61%) of black Protestants say they would want their doctors do everything possible to save their lives in this situation. The balance of opinion is similar among Hispanic Catholics: 38% would stop treatment, while 57% would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives.

White mainline Protestants are most inclined to say they would ask their doctors to stop medical treatment in these circumstances (72%), followed by white Catholics (65%) and white evangelical Protestants (62%). Among the religiously unaffiliated, 61% say they would want to stop treatment, while a third would tell their doctors to do everything possible to save their lives.

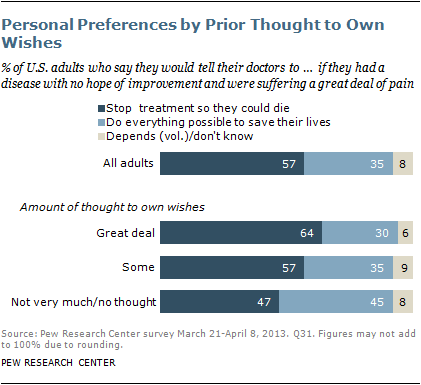

People who have given more thought to their personal wishes when it comes to end-of-life treatment issues are also more inclined to say they would stop their treatment so they could die if they were suffering from an incurable illness in all three of the circumstances addressed in the survey. For example, about two-thirds of those who have given a great deal of thought to their wishes (64%) say they would stop treatment so they could die if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain. Among those who have not given very much or any thought to their own wishes, fewer (47%) take that position.

Similarly, those who have either talked about or written down their wishes regarding end-of-life treatment are more inclined to say they would tell their doctors to stop treatment if they had an incurable disease and were suffering a great deal of pain.

General Views About End-of-Life Treatment

The Pew Research survey also asked a question about end-of-life medical decisions for other people. Respondents were asked to choose between two statements: 1) Doctors and nurses should do everything possible to save the life of a patient in all circumstances, or 2) Sometimes there are circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die. The survey question poses a stark contrast, and both options leave the hypothetical patient’s own wishes unstated. Nevertheless, this forced-choice question provides a useful gauge of overall public attitudes about end-of-life treatment.

Two-thirds of U.S. adults (66%) say there are sometimes situations when a patient should be allowed to die, while about three-in-ten (31%) say that under all circumstances medical personnel should do everything possible to save a patient’s life. The view that sometimes a patient should be allowed to die has remained the majority position in Pew Research surveys since 1990. However, the share of the public that says there are circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die has declined slightly over that period. More adults express an opinion today than did so in 1990, and the share of adults who say doctors and nurses always should do everything possible to save a patient’s life has grown.

Compared with 1990, all age groups are now more inclined to say that medical personnel always should do everything possible to save a patient’s life. However, this change over time is especially pronounced among younger generations.6

Overall views about end-of-life medical treatment are strongly associated with religious affiliation as well as race and ethnicity. White Catholics (80%) and white mainline Protestants (76%) are particularly likely to say there are circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die. A majority of white evangelical Protestants (68%) also hold this view. By contrast, a majority of Hispanic Catholics (66%) and 54% of black Protestants say medical staff should do everything possible to save a patient’s life in all circumstances.

Whites are more inclined than either blacks or Hispanics to say there are some circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die.

Opinions on this issue also tend to vary by age. About half or more of respondents in all age groups say there are times when a patient should be allowed to die. But older respondents are more inclined than younger ones to take this position. Younger adults ages 18-29 are most closely divided, with 54% saying there are circumstances in which a patient should be allowed to die and 43% saying medical personnel always should do everything possible to save a patient’s life.

As with personal preferences about end-of-life treatment, those who say they have given more thought to their personal wishes on these issues are more inclined to say there are times when a patient should be allowed to die.

Americans’ attitudes toward the cost and efficacy of medical care also are associated with their views about end-of-life treatment. The survey asked respondents whether medical treatments these days are generally “worth the costs because they allow people to live longer and better quality lives” or whether today’s medical treatments “often create as many problems as they solve.” About seven-in-ten (72%) of those who say medical treatments these days “often create as many problems as they solve” think there are times when a patient should be allowed to die. Fewer, though still a majority (62%), of those who say that medical treatments “allow people to live longer and better quality lives” think there are times when a patient should be allowed to die.

Overall views about end-of-life medical treatment are not strongly related to political party. Democrats are somewhat more inclined than Republicans to say that doctors and nurses should do everything possible to save a patient’s life in all circumstances, but these differences disappear after controlling for race and ethnicity. Among white, non-Hispanic respondents, there are no significant differences in overall views about end-of-life treatment by party affiliation.

Who Should Decide?

There is strong agreement in the general public that a close family member should be allowed to make medical treatment decisions when a patient is incapacitated and his or her wishes are not otherwise known (for example, through a written document or a prior discussion with the attending physician). About eight-in-ten adults (78%) say the closest family member should be allowed to make decisions on behalf of a patient in such circumstances, while 16% disagree. The balance of opinion on this question has remained steady since 1990.

However, views on another question involving proxy decision-making illustrate the degree to which attitudes on these kinds of issues often depend on the particular circumstances. The Pew Research survey asked about a hypothetical situation in which a child is born with a life-threatening birth defect. In this case, about four-in-ten adults (38%) say a parent has a right to refuse treatment on behalf of an infant, while a majority (57%) says the infant should receive as much treatment as possible, no matter what the defect.

Views about a parent’s role as decision-maker in these circumstances are strongly related to religion as well race and ethnicity and opinion about the moral acceptability of abortion. See Chapter 5 for details.

Physician-Assisted Suicide for the Terminally Ill

Public opinion on laws that would allow physician-assisted suicide is closely divided, with 47% approving and 49% disapproving of laws that would allow medical doctors to prescribe lethal doses of drugs for terminally ill patients who choose to commit suicide.7

Views on this issue are largely the same today as in the 2005 Pew Research survey. Surveys by Gallup have found a similar – and largely stable – divide in public opinion over whether doctor-assisted suicide is morally acceptable or morally wrong (45% say it is morally acceptable and 49% say it is morally wrong in Gallup’s most recent survey on the topic, conducted in May 2013).

There are sizable differences in opinion about this issue by race and ethnicity as well as religion. Whites are more inclined to favor laws allowing doctor-assisted suicide than are either blacks or Hispanics.

A majority of white mainline Protestants (61%) and about half of white Catholics (55%) approve of laws that allow physician-assisted suicide, as do two-thirds of religiously unaffiliated adults. However, by a margin of about two-to-one or more, black Protestants, white evangelical Protestants and Hispanic Catholics disapprove of laws that allow doctor-assisted suicide.

Beliefs About Suicide

Public attitudes about the morality of suicide tend to vary depending on the circumstances. About six-in-ten adults (62%) believe people have a moral right to end their own lives if they are suffering great pain and have no hope of improvement. A majority (56%) also believes people have a moral right to end their lives if they are suffering from an incurable disease. But far fewer see a moral right to suicide when a person is “ready to die because living has become a burden” (38%) or when a person is “an extremely heavy burden on his or her family” (32%).

Compared with surveys conducted in 1990 and 2005, there has been a modest uptick in the belief that suicide is morally justified under three of these four circumstances. The changes stem mostly from an increased share of the public taking a position on these questions (instead of saying “don’t know”) in recent years rather than a decline in the share saying there is not a moral right to suicide under these conditions. There is one exception to this pattern: Compared with 1990, there has been an increase in the share of the public that says suicide is not morally justified when a person is an extremely heavy burden on his or her family.

Views about the morality of suicide are strongly related to religious affiliation. White evangelical Protestants and black Protestants are least inclined to believe suicide is morally justified. About half or more white evangelical Protestants and black Protestants reject the idea of a moral right to suicide in each of the four circumstances included in the survey.

The unaffiliated, followed by white mainline Protestants and white Catholics, are especially likely to say there is a moral right to suicide under each of these circumstances. Among each group, about six-in-ten or more believe a person is morally justified in ending his or her life when suffering great pain with no hope of improvement and when facing an incurable disease.

Beliefs about the morality of suicide also tend to vary by race and ethnicity. On average, whites are more inclined than either blacks or Hispanics to say people have a moral right to end their lives under any of these four circumstances.

Aging and Life Assessments

Views about aging and perceptions about the quality of life in older age may play a role in people’s thoughts and opinions about end-of-life medical treatment.

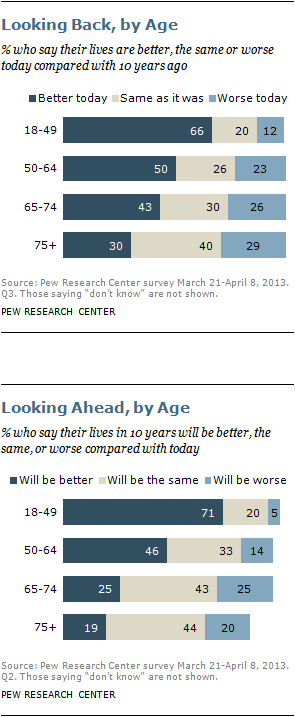

Assessments of one’s personal life are strongly colored by one’s place in the life cycle. When asked to reflect on their personal lives today compared with 10 years ago, older adults are much less inclined than younger ones to see improvement. Just three-in-ten adults ages 75 and older say their lives today are better than they were a decade earlier. By contrast, about twice as many adults ages 18-49 (66%) say their lives are better today than in the past.

By the same token, optimism for the future is harder to find among older generations. Only about a fifth (19%) of adults ages 75 and older expect their lives to get better in the future. By contrast, fully 71% of adults under age 50 expect their lives to be better in 10 years, and 46% of those ages 50-64 are optimistic that their lives will improve.

However, assessments of present life circumstances are only modestly associated with age. Fully eight-in-ten U.S. adults (81%), including 76% of those ages 75 and older, say they are satisfied with their personal lives today.

And assessments of life in specific domains – including financial status and social relationships – differ only modestly across age groups, with one notable exception – health status, which is inversely related to age. A third of adults under age 50 say their health is excellent. Only about half as many adults ages 65 and older say the same (16% each among those ages 65-74 and those ages 75 and older).

Ratings of social relationships, such as the number of friends one has, are only modestly related to age. Marital status tends to vary with the adult life cycle, but a majority of those who are married – whether they are older or younger – tend to say their relationship with their spouse is excellent.

And while fewer adults ages 65 and older are in the workforce, ratings of personal finances are not strongly associated with age. For example, 17% of adults ages 75 and older consider their personal financial situation to be excellent, compared with 11% among adults ages 18-49 and 13% among those ages 50-64.

The Pew Research survey also explores public views about the conditions that make for better quality of life in older age. Several characteristics and functions are seen by at least four-in-ten Americans as “extremely important” for a good quality of life in older age, including being able to talk or communicate with others (49%), being able to feed oneself (45%), getting enjoyment out of life (44%) and living without severe, long-lasting pain (43%). A somewhat smaller share says other qualities are extremely important for a good quality of life in older age, including long-term memory for the important people and experiences in one’s life (37%), feeling what one does in life is worthwhile (37%) and being able to dress oneself (36%). Three-in-ten adults say that having short-term memory about events that happened today is extremely important for a good quality of life in older age.

Older adults, especially those ages 75 and older who may have learned to live with some of these characteristics as part of their everyday lives, are less inclined than younger generations to rate all but one of these characteristics as extremely important for a good quality of life. (There are no age differences in the perceived importance of being able to dress oneself.) However, within all age groups, the largest share agrees that being able to communicate with others is extremely important.

About the Survey

Issues surrounding the end of life have sparked public debate for many decades and loom large in the lives of many Americans. This survey is part of the Pew Research Center’s ongoing effort to track public views about end-of-life medical treatments and, more broadly, bioethical questions at the intersection of religion and public life. Pew Research first conducted a survey on this topic in 1990, and a follow-up study was completed in 2005, shortly after the legal battle over treatment for Terri Schiavo drew national attention.8 Much has changed in the ensuing years, including dramatic increases in health care costs and more than a decade of public conversation over health care access and delivery, which continues today.

This is the second of two major reports by the Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project on the findings of a survey on bioethics questions. The first survey report, “Living to 120 and Beyond: Americans’ Views on Aging, Medical Advances and Radical Life Extension,” which was released in August 2013, explored attitudes about the prospect – still largely speculative – of living dramatically longer lives. This second report looks, instead, at the current state of medical treatments for the seriously ill. It explores public attitudes and beliefs about end-of-life medical treatment as well as physician-assisted suicide and the morality of taking one’s own life. The survey was conducted by telephone on landlines and cellphones from March 21 to April 8, 2013, among a nationally representative sample of 1,994 adults. The margin of error for the survey is plus or minus 2.9 percentage points.

Many Pew Research staff members contributed to the development of this survey and the accompanying reports. Senior Researcher Cary Funk was the principal researcher on the survey and the lead author of the report. Senior Researcher David Masci was the principal writer of two companion reports (described below). Their efforts were guided by Religion & Public Life Project Deputy Director Alan Cooperman and Project Director Luis Lugo. The survey questionnaire and analysis benefited from the guidance of a number of others at the Pew Research Center, including Andrew Kohut, Scott Keeter, Paul Taylor, Susannah Fox, Jon Cohen and Alan Murray. Data analysis and number checking assistance was provided by Jessica Hamar Martinez and Elizabeth Sciupac. Other staff who contributed to the report include Sandra Stencel, Erin O’Connell, Michael Lipka, Joseph Liu, Tracy Miller, Liga Plaveniece, Katherine Ritchey, Stacy Rosenberg and Bill Webster. Fieldwork for the survey was ably carried out by Princeton Survey Research Associates International.

Roadmap to the Report

The remainder of this report details the survey’s findings on end-of-life medical treatment and related issues, including aging and suicide. The first chapter looks at public views on laws allowing physician-assisted suicide. The second chapter covers beliefs about the morality of suicide under different conditions. The third chapter goes into detail on the public’s personal preferences for end-of-life medical treatment, how much attention people have given to end-of-life issues and what, if any, efforts they have taken to communicate their wishes for treatment. The fourth chapter looks at public attitudes on end-of-life medical treatment in a more general context and how those views have changed over time. The fifth chapter explores views about proxy medical treatment decisions for adults as well as for infants born with life-threatening defects. The sixth chapter looks at the public’s views on aging in general and levels of personal life satisfaction as they relate to age and to end-of-life treatment issues.

Together with the survey results, Pew Research is releasing three accompanying pieces. “To End Our Days: The Social, Legal and Political Dimensions of the End-of-Life Debate” presents an overview of the public debate on these issues in the last half-century in the U.S. An interactive timeline highlights key events and developments on the issue. “Religious Groups’ Views on End-of-Life Issues” describes what 16 major American religious traditions teach about one controversial aspect of the debate: physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia.

Photo Credit: © Tim Pannell/Corbis